Ben Fama: What do you think of celebrity culture?

Vanessa Place: What other kind is there?1

American poets in the era of social media are obsessed with celebrity – and especially with celebrity misfortune. Consider some of the following books written just in the past few years: Tan Lin’s Heath, Lara Glenum’s Maximum Gaga, Kevin Killian’s Action Kylie, Julia Bloch’s Letters to Kelly Clarkson, Kenneth Goldsmith’s Seven American Deaths and Disasters, Lonely Christopher’s Death & Disaster Series. The first four titles contain the name of a celebrity; the last two take their titles from Andy Warhol’s Death and Disaster paintings. Far more examples can be cited.2 The two most influential progenitors of this subgenre may be Warhol and Frank O’Hara – but it is also possible that this writing demonstrates features of other genres, such as fan fiction.3 Works such as Kate Durbin’s E! Entertainment, Morgan Parker’s “Beyoncé on the Line for Gaga” or Cecilia Corrigan’s “B-Day” (also about Beyoncé Knowles) engage in specific reinterpretations and rewritings of reality TV, film and popular music. Like fanfic, this poetry poses important questions with regard to transmediation, high culture vs. mass culture, privacy, the mediatization of fame, and the nature of celebrity and microcelebrity.4 Poetry about celebrities tends to be highly conscious of how gender is represented in mass culture, and should be of interest to literary readers and new media theorists beyond the range of traditional poetry audiences.

Ironic identification with stars is uncommon in modernist poetry. Celebrities do make occasional appearances in pre-1960s American poetry, but not with the frequency and intensity that they do in the poems I discuss here. The recent surge of interest in celebrity on the part of poets in the past ten years coincides with the emergence of social media and ubiquitous computing, and new media platforms are often discussed in the writing itself.5 Poetry about celebrities often theorizes poets’ own fame (or lack thereof) in relation to mass culture, in turn drawing attention to the construction of poetic communities. As Alice Marwick notes, “Media and celebrity are inextricably intertwined.”6 And as Lev Grossman writes, “Writing and reading fanfiction isn’t just something you do; it’s a way of thinking critically about the media you consume…”7 Much the same could be said of recent poetry about celebrities. In treating poets as critical consumers of new media and in delineating “celebsploitation” poetry as a distinct subgenre, I argue that poets demonstrate complex forms of identification (ironic or otherwise) with celebrities, and in particular with two main types, “bad stars” and “banal stars.”

In deploying the term “celebsploitation,” I do not mean to imply that poetry about celebrities is inherently exploitative; rather I mean for the term “celebsploitation” to be understood in a somewhat playful sense. While I recognize that the term conveys pejorative connotations, this essay attempts to explore this writing without resorting to value judgments that would imply that poetry is superior to mass culture or celebrity culture. Nor do I mean to suggest that these poets are unfair to celebrities, or that these poets are “selfploitative” in order to achieve fame. Although I do identify a number of patterns and tropes common within this work, I do not find this poetry at all simplistic or opportunistic; on the contrary, I find it deeply engaging and very much of our historical moment.

Warhol, O’Hara and “Bad Stars”:

From the Necrophilic to the Vicarious

Among the best-known poems about celebrity misfortune is Frank O’Hara’s “Poem (Lana Turner Has Collapsed),” which he wrote on the Staten Island Ferry en route to give a reading with Robert Lowell on February 9, 1962.8 In some respects, “Lana Turner Has Collapsed” is a whimsical rewrite of “The Day Lady Died.” Both poems draw on headlines from the New York Post. O’Hara had been writing poems about celebrities since the death of James Dean, whom he revered. In poems such as “The Day Lady Died,” O’Hara introduced his signature I-do-this, I-do-that style, which in today’s terms we might think of as lifestreaming.9 O’Hara, in effect, is responding to celebrity news on the fly. In Alice Marwick’s definition, “Lifestreaming is the ongoing sharing of personal information to a networked audience, the creation of a digital portrait of one’s actions and thoughts.”10 If we remove the “digital” from this formulation, we have a fair approximation of O’Hara’s mode in the I-do-this, I-do-that poems. As numerous commentators have noted, the thematization of friendship and of consumer society is crucial to O’Hara’s mature poetics.11 Mark Ford poses the question: “How many male poets of the fifties presented themselves in the act of shopping? Certainly you don’t find Robert Lowell or Anthony Hecht recounting expeditions to Bloomingdale’s.”12 When O’Hara first published “For James Dean,” Joe LeSueur describes

how the poem created a small stir. In the New Republic, a writer named Sam Astrachan criticized the poem for implying that Hollywood or society at large was responsible for the untimely death… And the final stanza—

Men cry from the grave while they still live

and now I am this dead man’s voice…—sounded morbid to one Turner Cassity, who wrote in a letter to the editor of Life magazine: ‘The James Dean necrophilia has penetrated even the upper levels of culture,’ a view shared by the ever-critical Paul Goodman. ‘What does Frank think he’s doing, writing poems about dead movie stars?’ he said to me one night at the San Remo.13

The reaction described by LeSueur points to many of the perennial anxieties aroused by writing about celebrity misfortune. For Cassity, O’Hara’s poem is a kind of pop insult to the “upper levels of culture” that presumably constitute Poetry’s readership. For Goodman too the poem seemed too morbid, or perhaps too vicarious. By the end of the poem, O’Hara is ventriloquizing the fallen Dean – something many readers in 1955 seemed to consider in poor taste.

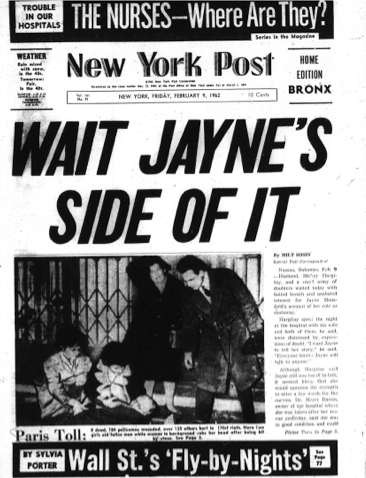

By 1962, O’Hara was an expert at reflecting on news as he encountered it in the course of his everyday life. Looking at the source article for “Lana Turner has collapsed” confirms that O’Hara wrote the poem on the day in question; it also reveals that he rewrote the headline, and that he left out details that might have revealed more about Lana Turner: he might for instance have noted that Turner was in the company of her fifth husband or that she was drinking with Dean Martin (one might wonder: who couldn’t Dean Martin drink under the table?).

The poem, we could say, isn’t really about Lana Turner; it’s about how the poet identifies with a celebrity mishap. The cover of the Post that day reveals that the weather – “Rain mixed with snow; in the 40s” – is exactly as O’Hara describes it.

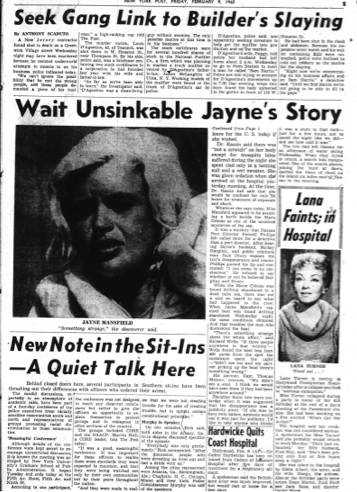

It also reveals a prototypical situation in which celebrity gossip is prioritized over tragedy. The screaming headline refers to Jayne Mansfield, but the photograph is of a tragic event in Paris: “8 dead, 184 policemen wounded, over 125 others hurt in leftist riots. Here two girls aid fallen man while woman in background rubs her head after being hit.” Meanwhile, Jayne Mansfield was having an affair (a topic the Post, despite its giant headline, treats with surprising circumspection), and Lana Turner had collapsed and was admitted to the hospital. All of this is treated on page 5, where the Mansfield story dwarfs the Turner story. Thirty years later, in a 1996 letter, John Updike was to refer to this poem as one of O’Hara’s “silliest and emptiest.”14 But that was precisely the point – the spontaneous frivolity of the poem was a direct reply to the formal strictures of established writers such as Lowell and Updike.15

The Lana Turner poem was not published until 1964 in Lunch Poems, and it is unlikely that Warhol would have known of it at the time he created his Death and Disaster paintings, a series that took shape after the death of Marilyn Monroe in August 1962.16 As Kenneth Goldsmith suggests plausibly in the afterword to Seven American Deaths, “the modern era of media spectacle begins with the John F. Kennedy assassination” – presumably due in large part to the role of television.17 Nonetheless, O’Hara and Warhol were both fascinated by the spectacle of mediatized death well before the Kennedy assassination. Warhol’s great innovation in the Death and Disaster paintings, according to Douglas Fogle, was his conflation of celebrity misfortune with everyday tragedy:

Monroe’s image was as much an homage to a recently departed American icon as it was a reflection of the rapaciousness of both Hollywood and the media in creating, consuming, and discarding stars. What is clear from Warhol’s work is that his early paintings of celebrities were often just as much ‘disasters’ as the works that were officially given that name. Monroe herself was a disaster, a ‘bad star’ if you will, having flamed out like a supernova after a phenomenal rise to stardom.18

The “bad star” sets the stage for the poetics of celebsploitation. The poet or artist can identify with the star as the victim of a rapacious culture industry, or in some cases, the poet or artist might even demonstrate a kind of schadenfreude.

One might go so far as to suggest that Warhol invented “disaster porn.” Famously, Warhol claimed that “when you see a gruesome picture over and over again, it doesn’t really have any effect.”19 Warhol’s juxtaposition of celebrities and everyday disaster did seem to hit a nerve, however. The paintings of “bad stars” like Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, Jackie Kennedy and Elvis Presley are among Warhol’s most recognizable and valuable works. In their fashion, these were all stars whose careers had peaked (the Elvis painting is based on a film still from his appropriately titled 1960 B-Movie Flaming Star) and/or who had suffered profound tragedy (Marilyn Monroe and Jackie Kennedy). In response to the question “Why did you start these ‘Death” pictures?”, Warhol replied: “I believe in it.”20 Warhol was famous for giving non-answers, but this answer is particularly intriguing. On the surface, to “believe” in death is nihilistic or cynical. But if death is never represented directly in art, perhaps this is its own kind of evasion or mystification. Death is, in a manner of speaking, the ultimate celebrity misfortune, and accordingly the untimely deaths of Marilyn Monroe, James Dean and Michael Jackson have all been the subject of multiple poems. The title of a recent poem by Ana Božičević, “The Day Lady Gaga Died,” neatly plays on the connection between fame and death – to be a star whose fame has been eclipsed (as Norma Desmond knew) is akin to being dead.21 Why after all should the death of a celebrity be any more significant than the death of any other person? A central problem with celebsploitaiton is naïve overidentification. And yet if the poet or artist has enough ironic distance from the celebrity in question, then the problem might be underidentification.

Transmediation and the Question of Microcelebrity

We live in a society bound together by the talk of fame.

—Leo Braudy22

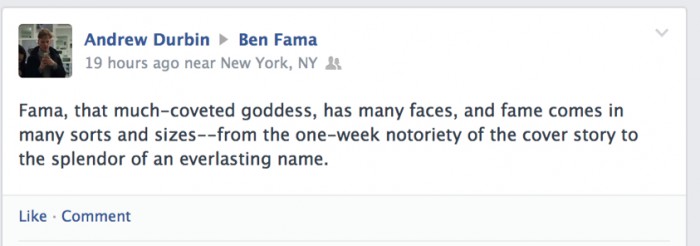

Consider the following Facebook exchange between two poet-friends who co-edit Wonder Press:

Andrew Durbin has wittily appropriated the first sentence of Hannah Arendt’s introduction to Walter Benjamin’s Illuminations.23 Who can we consider the audience for this meta-reflection? The post is on Ben Fama’s timeline, so presumably some fraction of Fama’s 2900 Facebook friends might have read it, as well as some fraction of Durbin’s friends. In an interview with BOMB Magazine, Durbin (who was born in 1989) speaks directly to the power of social media for younger writers:

Most of us don’t interact with an author through their work, but through their public persona on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr. That’s how a lot of writers throw out their ideas – that’s where the work lives. I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing. As a culture we demand, and always have demanded, access, as much of it as we can have. The illusion of social media is that it grants or increases that access. This was something of an issue recently with Josef Kaplan’s Kill List. The response to that poem happened almost exclusively in social media and was about social media – about what we know about one another, what we can say about one another.24

Durbin’s reflections align well with recent studies of social media, especially with Alice Marwick’s work on the emergence of microcelebrity, a category she and others argue emerged with blogging and social media.25

Authors can now publish immediately in semi-formal, and in some cases semi-private, contexts online. Facebook and Tumblr reward those who post frequently or who amass “likes” or “shares.” For Marwick, this has the potential to lead users of social media to overpost and to overshare – causing anxiety among users and provoking intense competition over status.

“Is there a relation between the internet and madness?” Ben Fama asks on the first page of his Cool Memories. That question has preoccupied many, including those who advocated adding the diagnosis of “Internet Addiction Disorder” to the DSM-V.26 Fama’s “Sunset” cleverly plays on the poet’s fascination with social media and lifestreaming. When first read aloud in public, the poem was titled “Selfie,” but the author changed the name prior to publication (perhaps because the previously little-known term had become the OED word of the year in 2013). “Sunset” begins by offering advice about what to do in case of a mass shooting: “You need to come up with a plan for what to do when you encounter an active shooter situation,” but the poem quickly digresses into a series of reflections on fame and notoriety.27 In a deadpan tone, Fama notes that “95% [of shooters] profile as white males 18-44 years, who have a personal trail through psychiatry, therapy and are actively maintaining a diary and social media blog.”28 The poet does not make public whether he has a “trail through psychiatry,” but in other respects Fama would fit the profile, so to speak, and particularly crucial here is his own self-professed obsession with social media. A few paragraphs later, Fama offers this ironic self-critique: “i check my klout score. klout amalgamates influence across a range of media networks. i attenuate this anxiety with a one hitter, the neon purple bat. i know i’m in a film because i’m sitting next to normsies at lunch.”29 Ironies abound in this passage: the speaker considers himself not to be a “normsie,” and yet his online status causes him anxiety. He is neither famous nor exactly anonymous. The poem concludes, ingeniously to my mind, with the line “john ashbery. im going to miss you when you rebrand.”30

What does it mean to think of John Ashbery, perhaps the most well regarded living American poet and the last living member of the original group of New York School Poets, as a brand name? The line implies that death is a form of rebranding. Rather than the death of the author we have the death of the brand. What currency does the brand New York School Poetry have? Is Fama, who was born in 1982, a New York School poet? And if so, is he fifth or sixth generation? Or has the brand been watered down? Is it now available to everyone? Can poets self-brand? Or do they need a movement or rubric under which to place their work? Vanessa Place has gone so far as to found her own parodic poetry production company, VanessaPlace, Inc.31 Poets have also actively resisted being labeled or branded. Bernadette Mayer concluded her contribution to The L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Book with the statement “work your ass off to change the language & don’t ever get famous.”32 That statement itself now has a kind of limited fame within poetry circles, if not within the culture at large.

When poets write about celebrities they are often self-consciously exploring their own fame, or lack thereof. This passage from Kevin Killian’s Action Kylie hilariously explores a kind of negative identification based in the safety of poetry’s small audience:

I think I like [Kylie Minogue] because she reminds me of myself… like Kylie I can stretch out a second or third rate talent and make it mean something by a) insisting on its smallness; b) attempting to push the envelope, usually by collaboration with others and c) feeling no guilt when, in a corner, at the end of my tether, or upset with something in my personal life, I retreat to my roots and produce version XYZ of the thing I know you’ll like from me.33

Kylie Minogue isn’t a “bad star” for Killian; she is a reassuringly mediocre one. Rather than inducing status anxiety, Kylie alleviates it. Killian wonders throughout the book why Kylie has never been as popular in the U.S. as in the rest of the world. He also wonders why her American fan base seems to be comprised largely of gay men. Liking Kylie is oddly a mark of difference, rather than sameness. Killian’s forms of identification with her are far from simple. He suggests that “There’s an anxiety in declaring oneself a Kylie fan – similar to how coming out used to feel.”34 Coming out is, in some sense, the ultimate metaphor to describe the negotiation between private life and public life.35 Or perhaps, as Killian suggests, it used to be, in that it much more strongly marked one as a member of a marginalized subcommunity. Here again, Killian’s ironies are multiple: being a member of a subcommunity can allow one to collaborate with others and to resist succumbing to the myth of lone genius. Killian’s humor about his own talent may be self-deprecatory in the extreme, but it is worth noting that his work has been strongly characterized by collaboration (he has collaborated with Barbara Guest, Leslie Scalapino, Peter Gizzi, Dodie Bellamy and Lewis Ellingham, among others). This stellar list by itself ought to give us pause. Marwick maintains that “Micro-celebrity is a state of being famous to a niche group of people, but it is also a behavior: the presentation of oneself as a celebrity regardless of who is paying attention.”36 It is likely the case that Kylie Minogue is not paying attention to Killian, but it may ultimately be liberating for Killian to be famous only to a niche group of those who compose his community of poetic production and reception.

Privacy, Surveillance and Voyeurism

Our society is not one of spectacle but of surveillance.

—Michel Foucault37

It’s this impulse – gears shifting downward from public to private – that Kylie understands and illuminates beautifully.

—Kevin Killian38

Like Killian’s Action Kylie, Andrew Durbin’s “Prism” explores a pop star the poet finds both generically banal and mysteriously captivating at the same time. For Durbin, “[Katy] Perry is beautiful by nonspecific design, accumulating color and fabric without ever fixing a permanent look, except perhaps vague kitsch. (Itself chic at present.) I cannot identify what draws me to her.”39 Like much of Durbin’s recent work, “Prism” toggles back and forth between everyday life and celebrity news. “Prism” also contains a significant passage that could be classified as fan fiction in which the poet has dinner with Perry. Durbin and Perry, together with a character repeatedly referred to only as Perry’s “current boyfriend” and a mysterious political figure referred to as “[REDACTED],” engage in a conversation about whether two members of the boy band One Direction are gay or not. Perry seems unaware that her new album, Prism, is titled for the NSA’s surveillance program, until [REDACTED] offers the following Pynchonesque monologue implying that [REDACTED] might have more information than is publicly available:

‘The proof [that Louis and Harry of One Direction are gay] is in their entire team, which is not only composed of assistants, producers, and other handlers, but also: a corporate mass surveillance program – known in some circles as DARK HORSE – run by a shadowy group of privacy gurus at great distance from their immediate circle but which keeps close tabs on them, and a number of other important celebrities, in order to control and manipulate their private lives, creating an environment of paranoia that ensures they behave on-brand and according to certain market-friendly values. Whatever they do is what gets out; the music industry – Hollywood, too – learned long ago that, in addition to controlling the media and its “narratives,” they had to control their product on the most basic level, that is, on the level of their personal lives by essentially erasing that privacy and colonizing what remained. This control ultimately proves effective in terms of curbing certain off-brand impulses, like, say, gay sex among the boys of One Direction, by creating a restrictive, paranoid culture of information-sharing.’40

At this point in the conversation, Perry is offended and she and her entourage depart abruptly. Later in the poem, the poet offers this reflection, which locates him specifically within omnipresent systems of data collection:

‘Dark Horse’ evokes… the highly organized systems of information management that cache, tag, and categorize both the metadata of these remnants (text message: ‘hi what r u doing rite now its late i know’; recorded as ‘Message containing no flagged content sent at 3:02:42AM 11/08/13 from Maison O, 98 Kenmare Street, Manhattan, New York City, New York 10012; born 09/28/89; profile clear of flagged content. SEE MORE).’41

The poet has here – against the advice of most privacy experts – revealed a considerable amount of data (or rather metadata) about himself, including his date of birth and where he had dinner. Viewed from the perspective of the NSA his communications pose no threat; there is no content to flag.

Durbin is, in a sense, presenting himself as a “normsie” in the eyes of those who would surveil his activities. Allusions to “normsies,” “normopaths [Glenum]” and “normcore” abound in the recent poetry of celebrity. The bad star is out of control or past his or her prime; the banal star is too much in control, or too well handled by his or her public relations team. Durbin suggests in his BOMB interview that

celebrities help us to develop a tolerance for reality and can manufacture, disrupt, change, subvert, regenerate, or create fantasy…. The illusion is that they are radically original, or separate and above, which isn’t to say that they’re not, but they’re no more radically original than the rest of us. They – and their PR teams – are just better at creating a narrative of their own originality, or their own difference. They identify very quickly what it is about our fantasy of the world that can be harnessed – or, really, made into a product that they can then sell back to us.42

The banal star is the star who was either never original, or whose originality has been eclipsed. The banal star, as in the case of Action Kylie above, induces a different kind of identification. In the work of Kate Durbin, Julia Bloch and Lara Glenum, the banal star can become an icon for some of the most persistently sexist representations of female sexuality. In one of her fan letters to Kelly Clarkson, Bloch writes:

Dear Kelly,

Clutched in femininity’s dystopic embrace as if it were a big clammy hand from the deep, I watch the bright box, forgetting to blink, I know I should be turning to the book and reading and writing but the images keep coming, trafficking my sense for the real and the room. The screen is sometimes described as an eye or a tube filled with celebrity jelly. I can’t see any of your pores; I know I shouldn’t but I want you to be a real girl, muscular, with a hair shade that doesn’t make a sound.43

Bloch would like to turn away from the compulsory femininity displayed onscreen and return to a (presumably more serious) book, but finds it impossible. She wants Kelly Clarkson to be more real than she is, but what can this mean in this context? American Idol winners are both ordinary in their humble appeal, and extraordinary in that they are (in theory) turned into celebrities by the sheer will of ordinary people like themselves. They owe their stardom paradoxically to their very unstar-like origins.

The banal star offers far less than the bad star in terms of celebrity gossip potential – but the banal star is far more likely to be a role model with potentially adverse consequences for impressionable fans. Kate Durbin’s E! Entertainment is a sophisticated response to said TV channel’s interest both in delivering celebrity news and meta-entertainment industry news – as well as in fostering reality TV programs that turn ordinary people into celebrities. Like the channel she channels, Durbin moves back and forth effortlessly between “Real Housewives of __________” and the trials and travails of bad stars such as Anna Nicole Smith, Kim Kardashian and Lindsay Lohan. Many of the book’s vignettes end with seemingly superficial details, such as descriptions of the lips of the speakers. Beneath many of these details, however, lurks the grotesque. “Wife Drita smiles; lips red, teeth white,” for instance, operates by a kind of synecdoche wherein the speaker is represented by a body part.44 In the aggregate, the “real housewives” are profoundly banal; their lives revolve around their husbands, and if they have any celebrity it is due to their husbands or to being on the show. The coverage of celebrity trials is even more banal in Durbin’s rendering. The book ends with a long write-through (or extended reimagining) of the show The Hills in which the show’s main characters endlessly castigate one another – in effect performing a pointless auto-misogyny or woman-on-woman verbal violence.

Perhaps because the star after which it is named is herself so protean a figure, Maximum Gaga by Lara Glenum is one of the most difficult to classify of recent books of celebrity poems. Set at the bottom of the sea, Maximum Gaga parodies the “seapunk” movement, in which mermaid attire is deployed in a whimsical, nostalgic manner. The book contains countless invocations of the grotesque and depictions of vague holes and slits on nearly every page. The book also contains four poems titled “Normalcore.” I read this complex work as a dialogue between the normal and the abnormal, the beautiful and the grotesque.45 In a playlet titled “A Burlesque in a Sewer” near the book’s midpoint, a “chorus of trannie mermaids” sings:

The Body is the Inscribed Surface of Events!

A Volume in Perpetual Disintegration!

The Body is Always Under Siege!46

These anthemic sentiments are in line with post-Judith Butler feminism – but are they in line with Lady Gaga’s self-presentation? Among the most self-conscious of contemporary celebrities, Lady Gaga has both strategically deployed her own beauty (and nudity) at the same time that she has drawn attention to how the media objectifies female performers (by, for example, famously wearing a dress made out of raw beef to the MTV Video Awards in 2010). Gaga’s avid fan base – known as Little Monsters – would seem to be sympathetic to non-beautifying self-presentation strategies. Glenum does not weigh in on these aspects of Lady Gaga’s celebrity; Glenum’s intention, I take it, is to offer a darkly whimsical thought experiment on female representation. Maximum Gaga, that is to say, offers a series of intense, bawdy dialogues having to do with the repression and liberation of female sexuality. Glenum plays on the contradiction of the “pathologically normal” and the “normopath” repeatedly in Maximum Gaga. But by the book’s end (similarly perhaps to the filmic techniques of Harmony Korine), it is almost impossible to tell the difference between the beautiful and the grotesque.47

The Project of Attention and the Collective Livestream

If I’m not online, I’m nothing.

—Andrew Durbin48

Tan Lin’s Heath restricts itself to a fairly limited span in terms both of its focus and its composition. As Lin explains in an interview included within the book itself:

the time frame for writing, publishing and distributing was radically compressed, at least for a book, so that its surrounding textual composition strategies are more fully integrated with the ‘finished’ book itself. It was composed out of a rewritten preface to a novel I had just completed. I rewrote it and added a huge amount of other material. So what was so interesting here, compositionally, was the total time from writing to publication – it was something like 5 months and it was written in under a few weeks.49

Embedded within its covers, the expanded Heath Course Pak includes its own timeline for composition:

January 22, 2008 Heath Ledger dies.

Most of the book was written after this point, and the bulk of the drafts date from February through late June 2008, so about five months. During this period, 23 drafts were done. Most of the stuff written prior to Heath’s death in fall 2007 was discarded. The white out article was recycled from an earlier article, which I had sent to Artforum. The earliest material from the Pickwick Arms is the preface to a novel, Our Feelings Were Made by Hand. It thus dates earlier.

Ms. turned in to Danielle Aubert July 14th, 2008.

Ms. turned into Manuel by Danielle in InDesign. July 16, 2008.

Book arrives from printers October 2008.50

I want to suggest that this constraint approximates what Michael Sheringham refers to as a “project of attention.”51 Projects of attention typically involve the recording of everyday experience over specific periods of time. Georges Perec’s “Attempt to Exhaust a Place in Paris,” which took place over three days, is an exemplary “project of attention.” Considered as a “project of attention,” Heath is not so much a personal lifestream as much as it is a collective livestream. Lin’s treatment of celebrity death depends on multiple remediations from a baffling array of sources (blogs, online newspapers, RSS feeds, chatrooms, and even notecards written by his students). Heath also exists in a number of versions and editions.52 Unlike many conceptual practitioners (such as Kenneth Goldsmith), Lin has made versioning a central aspect of his practice. When one of his books goes out of print, Lin will often update or revise for a new edition. Lin’s ambient poetics thwarts our ability to pay attention to the collective livestream of data; it also undermines our very notion of what constitutes a stable printed text.

Lin’s interest in celebrity is also part of a larger onslaught on originality. “Originality is the last remaining waste product (muda) of creative practices and remains to be eliminated within aesthetic production and/or distribution systems,” he writes.53 In the larger context of the Heath project, Heath Ledger becomes merely another news feed, a bad star who becomes increasingly banal through overexposure. Lin offers a critique of celebrity exceptionalism at the same time that he explores his own fascination with the Heath Ledger story. Lin, to my mind, offers the strongest possible response to ideologies of “platformed individuality” by drawing continual attention to the many platforms upon which his writing operates. In his history of fame, Leo Braudy writes that:

To the extent that the desire for fame demands a solitary eminence, it too easily becomes a rejection of fellowship, a threat to a just society, a dead end of individualism…. The modern formulation might be that the urge to fame can become a threat when it too consciously replaces any other goal of personal or public good.54

By making his students his co-authors and titling the second edition of the book Heath Course Pak, Lin also foregrounds his own institutional position as someone who is neither anonymous nor famous. Heath offers no ideal of personal or public good, but it does satirize the literal “dead end of individualism,” when the dead star can only be an object of necrophilic reflection.

The Heath project also draws attention to the problem of “fan labor” – or “affective labor,” a typically feminized (and unpaid) form of immaterial labor.55 Although affective labor usually takes the form of positive affect, it can also take the form of negative affect. According to Arlie Hochschild’s The Managed Heart, emotional labor “requires one to induce or suppress feelings in order to sustain the outward countenance that produces the proper state of mind in others.”56 Another of Hochschild’s books, The Outsourced Self: Intimate Life in Market Times, suggests that even our most intimate feelings have been outsourced to the entertainment industry.57 The original full title of the 2008 version of Heath is plagiarism/outsource, Notes Towards the Definition of Culture, Untilted Heath Ledger Project, a history of the search engine, disco OS suggests something analogous.58 Who is doing the “work of mourning” in Heath if its authorship has been outsourced? Is it the students in Lin’s class at the Asian American Writer’s Workshop? Or is it the often-anonymous writers that Lin is openly plagiarizing? Adorno and Horkheimer claim in “The Culture Industry” that “Entertainment is the prolongation of work under late capitalism.”59 In the era of social media, this problem is particularly acute, given that social media users both generate and consume content, and especially given that celebrity news is typically a feminized discourse. Lin’s project, I want to suggest, thwarts any notion of a stable “edited self” by in effect largely refusing to edit on behalf of readers, who must do their own work of meaning-making.

Not all of the materials in Heath can be traced back to an online source. These charged lines, for instance, seem to have been written either by Lin or his students:

and because everyone I know

is white

and because whiteness could not be memorized, plagiarism was60

The lines seem to imply that whiteness and plagiarism are merely two forms of copying. Perhaps they also aim to counter stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans as being less original, or more likely to be overachievers and thus more motivated to copy the academic work of others. But “whiteness could not be memorized” also suggests that whiteness is a learned or remembered condition. Another untraceable quotation suggests that “memory is a species not of correspondence but of frequency.”61 Heath does not offer a comprehensive theory of memory, but it does imply that memory is unreliable as well as technology-dependent. Many images and textual fragments are repeated through the book. The “history of the search engine” dimension of the book (as embedded in its full original title) suggests that the book is an attempt to record “real-time” emotional reactions, and yet at the same time the book questions the extent to which those reactions are conditioned by pre-existing gender- and race-based modes of identification. Heath repeatedly elides individuated emotional response in favor of a collectively-sourced response:

The economic engine was a search engine, part SMS, part poem, part paid art review, part installation based practice, part retrieval system, part polemic. The writing of a news event like an art installation is indiscriminate, alternate, short ubiquity. Like SMS, it’s a place where desires are ranked and collapsed (contributor’s page) without angst, i.e. seven individuals worked to this. One person requested that they be listed as a pseudonym.

Ledger is part of the search engine mechanism as are his fans. To mourn collectively perhaps is to mourn “without angst.” And yet there also may be a kind of racial melancholy that pervades Heath.62 References to Jackie Chan are scattered throughout, as if to juxtapose the aging Asian action star with Heath Ledger as the forever young, white and beautiful bad star. Allusions to Brokeback Mountain abound in Heath, while curiously there are few references to The Dark Knight, Ledger’s last film. Brokeback not only featured Ledger as a bisexual man, it was also directed by Ang Lee, the first person of Asian descent to win an Oscar. The Heath project refuses to speak specifically to such aspects of Ledger’s cultural significance, but instead treats the actor as a kind of algorithm to explore and complicate patterns of identification across platforms.63

Lin offers an extended account of his writing process in Heath that bears reflection:

the core of the book is not procedural at all, which implies making a predetermined choice about the composition of a piece (i.e. the procedure) that will then guide the writing of the piece; in that sense I don’t think the process is something I personally connected with at a very specific moment. It was a mild intrusion or a barely noticed break or dilation or evanescence or hyperbole that I was interested in, in an overall ambient environment of which I was a part of, so it would be hard for me to say the interest was ‘mine.’64

In terms of undermining his own authorial agency, Lin’s brand of celebsploitation may be the most radical. Despite his avowed personal connection to the material, he does not say specifically how Ledger’s death affected him, rather he channels the media sources which presumably led him to feel a connection to a person he had never met. Moreover, Lin does not position his project as conceptual writing. He does not begin with a predetermined constraint in mind, but rather allows himself to drift with the material as it is continuously updated. This way of dealing with celebrity news may in the end be the most authentically mimetic of how we experience celebrity death: we are bombarded with multiple stories, multiple remarks from friends, and countless micro-updates. The death comes first, then comes the funereal reflection, and then come the toxicology reports. We are at all levels of society fascinated by this news that does not pertain to us directly in any way.

Coda

Critical works in the field of media theory are quickly dated. Many of the platforms mentioned in this essay did not exist ten years ago. Other platforms have either waned (blogging) or vanished entirely (MySpace). Given the level of flux that currently exists not only in terms of poetry publication platforms, but also in terms of the available platforms for the discussion of poetics and the (self-)promotion of poets, it is almost impossible to predict how social media will affect poetry in the long run.

During the course of writing this article, I Facebook friended almost all of the writers under discussion. I also asked for help in finding poems about celebrity misfortune, and the responses I received informed the selection of works I chose to write about. “In the future, everyone will be famous to 1500 friends,” I playfully posted during one afternoon writing session.65 I received about ten likes in the first fifteen minutes, and only a few thereafter. Warhol in one sense was right about fifteen minutes of fame, and in another sense he was wrong. The Warhol quote seems most appropriate to the television era, which seems already to be receding quickly. Hannah Arendt was more correct to suggest that “fame comes in many shapes and sizes.” Poets are often considered to partake of an outmoded, nostalgic or technophobic genre. My experience studying avant-garde poetry suggests the opposite: poets are unacknowledged legislators of new communications technologies. Rather than lagging indicators, they are leading indicators. Social media is altering the language we speak; it is also changing the poetry we read. But this is not a one-way street, to borrow the title of Walter Benjamin’s first book. At the time that Arendt wrote her introduction to his work (from which Durbin quotes earlier in this essay), Benjamin was virtually unknown. Now he is widely considered the greatest literary critic of the twentieth century, and one of its greatest media theorists as well. Nearly ninety years ago, he claimed in One-Way Street that “the book is already…an outdated mediation between two different filing systems.”66 Plus ça change: the book remains an outdated mediation, and yet the book remains the authoritative format for literary publication. In addition we now have countless filing systems and countless new topics for poets to draw from. An important role for scholars of contemporary literature is to write the ongoing histories of these mediations – between obscurity and celebrity, print and digital media, high culture and mass culture. As in Benjamin’s time, poets remain at the vanguard of exploring new forms of communication and collective identification.

“Vanessa Place talks with Ben Fama about Vanessa Place, Inc.” Bright Stupid Confetti, July 17, 2013, accessed February 20, 2014, http://www.brightstupidconfetti.com/2013/07/authors-on-artists-vanessa-place-talks.html. ↩

In addition to the works discussed in this article (and this is by no means a complete list), see Sarah Blake, Mr. West (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP, 2015) Brandon Brown, Flowering Mall (New York: Roof Books, 2012) and Top 40 (New York: Roof Books, 2014), Brian Joseph Davis, Portable Altamont (Toronto: Coach House, 2001), Ben Fama, Fantasy (Brooklyn: Ugly Duckling, 2015), Michael Friedman, Martian Dawn (New York: Turtle Point Press, 2006), Ronald Gross, Pop Poetry (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1967), Lauren Ireland, Dear Lil Wayne (Northampton, MA: Magic Helicopter Press, 2014), Trisha Low, The Compleat Purge (Chicago: Kenning Editions, 2013), Michael Magee, My Angie Dickinson (Canary Islands: Zasterle Press, 2006), Adrian Matejka, The Big Smoke (New York: Penguin, 2013), Monica McClure, Tender Data (Austin, TX: Birds, LLC), Sharon Mesmer, Annoying Diabetic Bitch (Cumberland, R.I.: Combo Books, 2008), Morgan Parker, Other People’s Comfort Keeps Me Up at Night (Chicago: Switchback Books, 2015), Robert Polito, Hollywood & God (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2009), D.A. Powell and David Trinidad, By Myself: An Autobiography (New York: Turtle Point Press, 2009), Sam Riviere, Kim Kardashian’s Marriage (London: Faber, 2015), Nicole Steinberg, Getting Lucky (Austin, TX: Spooky Girlfriend Press, 2013), Jennifer Tamayo, You Da One (Atlanta, GA: Coconut Books, 2014), Jess Tyehimba, Leadbelly: Poems (Seattle, WA: Wave Books, 2005) and Dana Ward, This Can’t Be Life (Washington, DC: Edge Books, 2012). There are indications too that stars are paying attention to poets. Shia LaBoeuf has cited Kenneth Goldsmith as an influence. James Franco has reviewed Polito’s book: “‘Hollywood and God’ Reveals the Dark Side of Tinseltown.” Vice, February 23, 2014, accessed February 24, 2014,

http://www.vice.com/read/hollywood-and-god-reveals-the-dark-side-of-tinsel-town.htm. Kathy Acker’s interview with The Spice Girls, although not a celebrity poem, makes for fascinating reading: “All Girls Together,” The Guardian, May 3, 1997, accessed February 10, 2014, http://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/all-together-now. In an interview with Holly Cassell, Forsyth Harmon discusses “celebsploitation” in terms of female objectification. The Le Sigh (February 2014), accessed February 4, 2014, http://www.thelesigh.com/2014/02/girl-spotlight-forsyth-harmon.html. Ted Rees and Brandon Brown maintain a blog “Celebrity Brush” about poets’ encounters with celebrities: http://poetsmeetcelebs.tumblr.com. Although Kenneth Goldsmith’s work is highly pertinent to this essay’s discussion of writing about celebrity misfortune, I have chosen not to address it here. This essay was written before the controversy emerged surrounding Kenneth Goldsmith’s performance “The Body of Michael Brown” on March 13, 2015. Michael Brown was not a celebrity; nor is the text of Goldsmith’s performance available for scholarly scrutiny. More relevant for consideration here would be Goldsmith’s chapters on the John Lennon assassination and on the death of Michael Jackson in Seven American Deaths and Disasters (Denver: Counterpath, 2013). For a broader historical consideration of celebrity in relation to American poetry, see David Haven Blake, Walt Whitman and the Culture of American Celebrity (New Haven: Yale UP, 2006). ↩For more on fanfiction, see Anne Jamison, Fic: Why Fanfiction Is Taking Over the World (Dallas: Smartpop Books, 2013) and especially Darren Wershler’s contribution “Conceptual Writing as Fanfic”: 363-371. Like most fanfic, most poetry is not published for profit. As Jamison writes, “Fanfiction blurs a whole range of lines we (mistakenly) believe to be stable: between reading and writing, consuming and creating, genres and genders, authors and critics, derivative and transformative works” (6-7). ↩

Following Wershler (who draws on Henry Jenkins), I am using the term transmediation loosely to suggest mediation not only across media (e.g. radio to print) but also across digital platforms (e.g. Facebook to Twitter). ↩

For more on poetry and portable ubiquitous computing, see the introduction to my book The Poetics of Information Overload: From Gertrude Stein to Conceptual Writing (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press, 2015). ↩

Alice Marwick, “Instafame: Luxury Selfies in the Attention Economy.” Public Culture 27.1 (Winter 2105): 137-160, 139. ↩

Qtd. in Jamison, Fic, xiii. ↩

For more on the poem’s composition, see Joe LeSueur, Digressions on Some Poems by Frank O’Hara: A Memoir (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004): 264-266. LeSueur specifies that it was the Post; I must admit, however, that I cannot prove with absolute certainty that it was. I do think it is overwhelmingly probable that it was the Post. The New York Times also recorded the event the same day, but in a brief column that gives no details to suggest that it could have been the item (or headline) that O’Hara saw. For more, see Andrew Epstein’s post “‘Lana Faints; In Hospital’: A Visual Footnote for Frank O’Hara’s ‘Poem (Lana Turner has collapsed)’” on Locus Solus: The New York School Poets Blog, March 7, 2014, accessed March 15, 2014, http://newyorkschoolpoets.wordpress.com/2014/03/07/a-visual-footnote-for-frank-oharas-poem-lana-turner-has-collapsed/. ↩

O’Hara first refers to his “‘I do this I do that’ poems” in September 1959 in “Getting Up Ahead of Someone (Sun).” Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara, ed. Donald Allen (Berkeley: UC Press, 1971), 341. ↩

Alice Marwick, Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Branding in the Social Media Age (New Haven: Yale UP, 2013), 208. ↩

See especially Andrew Epstein, Beautiful Enemies: Friendship and Postwar American Poetry (New York: Oxford UP, 2006), Lytle Shaw, Frank O’Hara: The Poetics of Coterie (Iowa City: U of Iowa Press, 2006) and Michael Clune, “Frank O’Hara and Free Choice,” in American Literature and the Free Market, 1945-2000 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2010): 53-76. For more on O’Hara and mass culture, see Andrew Epstein, “‘I want to be at least as alive as the vulgar’: Frank O’Hara’s Poetry and the Cinema,” in The Scene of My Selves: New Work on New York School Poets (Orono, ME: National Poetry Foundation): 93-121. ↩

Mark Ford, “A Poet Among Painters,” in A New Literary History of America, eds. Greil Marcus and Werner Sollors (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2009): 814-819, 817. ↩

LeSueur, Digressions, 63-4. ↩

Qtd. in David Lehman, The Last Avant-Garde: The Making of the New York School Poets (New York: Anchor, 1997), 350. ↩

For more on this, see Daniel Belgrad, The Culture of Spontaneity: Improvisation and the Arts in Postwar America (Chicago: U of Chicago Press, 1999). ↩

Warhol and O’Hara strongly disliked one another, but were well aware of each other’s work. For more on their relationship, see Reva Wolf, Andy Warhol, Poetry, and Gossip in the 1960s (Chicago: U of Chicago Press, 1997). ↩

Goldsmith, Seven American Deaths and Disasters, 173. ↩

Douglas Fogle, Andy Warhol/Supernova: Stars, Deaths and Disasters 1962-1964 (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2005), 16. ↩

Andy Warhol, I’ll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews, ed. Kenneth Goldsmith (New York: Carroll and Graf, 2004), 19. ↩

Warhol, I’ll Be Your Mirror, 18. ↩

Ana Božičević, Rise in the Fall (New York: Birds, LLC, 2013), 52. ↩

Leo Braudy, The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and Its History (New York: Vintage, 1997), vii. ↩

February 19, 2014. Note on social media quotations/screenshots: I have asked permission from all parties whose social media posts I have quoted, as I consider these semi-private communications. ↩

Andrew Durbin interviewed by Jacob Severn, BOMB Magazine (January 27, 2014), accessed February 25, 2014, http://bombmagazine.org/article/7523/. Josef Kaplan’s Kill List (Philadelphia, PA: Cars Are Real, 2013) and its reception merit consideration here. In part due to unresolved concerns regarding the quotation Facebook posts, I have refrained from a full discussion. Within a few days of publication, Kill List was followed by Joey Yearous-Algozin’s Real Kill List (Buffalo, NY: Troll Thread, 2013) [which printed Facebook comment threads related to Kill List], Sophia Le Fraga’s Chill List (Facebook and Twitter), and Rose Arthur’s Reading List, accessed February 25, 2014, http://hyperallergic.com/95889/reading-list/. One informant I spoke to referred to the collective reactions to Kill List as “Microcelebrity Death Match.” For more on the scholarly ethics of quoting from Facebook threads, see Marwick 295, footnote 22. ↩

For more on microcelebrity, see my article “Reading Robert Fitterman’s Now We Are Friends Through the Lens of Ten Media-Theoretical Terms.” Post45 Contemporaries, accessed January 21, 2015, http://post45.research.yale.edu/2015/01/reading-robert-fittermans-now-we-are-friends-through-the-lens-of-ten-media-theoretical-terms/. For parallel critiques of what is variously referred to as “networked individualism” or “platformed sociality,” see Jose Van Dijck, The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media (New York: Oxford UP, 2013) and Lee Rainie and Barry Wellman, Networked: The New Social Operating System (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2014). ↩

The debate over internet addiction is a large and complex one. For more, see the introduction to my Poetics of Information Overload. Writers such as Bernard Stiegler, Larry Rosen and Nicholas Carr maintain that internet overuse is a serious problem. Sherry Turkle, on the other hand, has argued plausibly that addiction is the wrong metaphor for technological dependency; see Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other (New York: Basic Books, 2011). ↩

Ben Fama, Cool Memories (Tuscon, AZ: Spork Press), 27. ↩

Fama, Cool Memories, 27. ↩

Fama, Cool Memories, 27. ↩

Fama, Cool Memories, 31. ↩

For more, see http://vanessaplace.biz/. ↩

Bernadette Mayer, “Experiments,” in The L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Book (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois UP, 1984): 80-83. ↩

Kevin Killian, Action Kylie (New York: In Girum Imus Nocte et Consumimur Igni), 52. ↩

Killian, Action Kylie, 51-2. ↩

I am thinking of course of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet (Berkeley: UC Press, 1990) and also of Deborah Nelson’s crucial study of confessional poetry, Pursuing Privacy in Cold War America (New York: Columbia UP, 2001). ↩

Marwick, Status, 114. ↩

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Vintage, 1977), 219. ↩

Killian, Action Kylie, 53. ↩

Andrew Durbin, Mature Themes (New York: Nightboat Books, 2014), 49. ↩

Durbin, Mature Themes, 50-1. ↩

Durbin, Mature Themes, 56. ↩

Durbin, BOMB, n.p. ↩

Julia Bloch, Letters to Kelly Clarkson (San Francisco: Sidebrow Books, 2012), 42. ↩

Kate Durbin’s E! Entertainment (New York: Wonder, 2014), 7. ↩

For more on Glenum’s interest in the “female grotesque,” see her “Theory of the Gurlesque: Burlesque, Girly Kitsch, and The Female Grotesque,” in Gurlesque: The New Grrly, Grotesque, Burlesque Poetics, eds. Lara Glenum and Arielle Greenberg (Ardmore, PA: Saturnalia Books, 2010): 11-24. ↩

Lara Glenum, Maximum Gaga (Notre Dame, IN: Action Books), 62. ↩

It should be noted that the celebsploitation poems by women that I survey in this essay tend to be much more concerned with the visual appearance of celebrities, as well as with normative standards for beauty and aging. For a recent examination of how female celebrities are represented in the media, see Sarah Projansky, Spectacular Girls: Media Fascination and Celebrity Culture (New York: NYU Press, 2013). ↩

Durbin, BOMB, n.p. ↩

Tan Lin, Heath Course Pak (Denver: Counterpath, 2012), n.p. ↩

Lin, Heath Course Pak, n.p. ↩

Michael Sheringham, Everyday Life: Theories and Practices from Surrealism to the Present (New York: Oxford UP, 2006), 388. Sheringham also cites the examples of Henri Lefebvre, Raymond Queneau and the Situationists. See also Andrew Epstein, “‘Pay More Attention’: Ron Silliman’s BART and Contemporary Everyday Life Projects.’” Jacket 39 (2010), accessed July 12, 2011, http://jacketmagazine.com/39/silliman-epstein-bart.shtml. ↩

For more on the multiple versions of Heath, see the interview near the conclusion of (the unpaginated) Heath Course Pak, where Lin observes, “Just as a film carries credits and titles in the opening sequences, and these credits are the result of numerous ‘authors’ who are fully credited as ‘authors,’ so too could Heath be said to invoke a large company of authoring devices/genres/software programs/inks/printing technologies/fonts/distribution systems/editorial practices/legal system/legislative bodies and individuals – though the distinction between the former and the latter is fudged.” ↩

http://directobjective.blogspot.com/2010/03/theres-no-such-thing-as-originality.html. ↩

Braudy, Frenzy, 593. ↩

For more on affective labor, see Michael Hardt, “Affective Labor.” boundary 2 26.2 (Summer 1999): 89-100, and Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham: Duke UP, 2011). See also especially Marwick 194-207. ↩

Qtd. in Marwick, Status, 196. ↩

Arlie Hochschild, The Outsourced Life: Intimate Life in Market Times (New York: Holt, 2012). ↩

The title page of the first print edition of plagiarism/outsource, Notes Towards the Definition of Culture, Untilted Heath Ledger Project, a history of the search engine, disco OS (La Laguna, Canary Islands, 2007) incorrectly notes the date of the book’s publication, which did not occur until 2008. It should be noted that the print and electronic editions of Heath differ substantially. The first print edition credits seven co-authors and Danielle Aubert, the book’s designer. Heath Course Pak credits five additional co-authors (or perhaps co-producers): Kristen Gallagher, Chris Alexander, Gordon Tapper, Danny Snelson and Tim Roberts. ↩

Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer. The Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments, trans. Edmund Jephcott and ed. Gunzelin Schmid Noerr (Stanford: Stanford UP, 2002), 109. ↩

Lin, Heath Course Pak, n.p. ↩

Lin, Heath Course Pak, n.p. ↩

I am thinking here of Anne Cheng’s The Melancholy of Race: Psychoanalysis, Assimilation, and Hidden Grief (New York: Oxford UP, 2001). ↩

Danny Snelson has convincingly read Heath through the lens of Actor-Network Theory. See “HEATH, prelude to tracing the actor as network,” accessed March 10, 2014, http://aphasic-letters.com/heath/. ↩

Heath Course Pak, n.p. ↩

Warhol in fact originally said “in the future, everyone will be world-famous for fifteen minutes.” Selected Interviews, xxv. He later dropped the “world-,“ and (re-)quoted himself saying the more familiar “In the future, everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes.” Andy Warhol and Pat Hackett, POPism (New York: Harcourt, 1980), 130. ↩

Walter Benjamin, “One-Way Street,” in Selected Writings, Vol. 1: 1913-1926, eds. Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1996): 444-489, 456. ↩

Article: Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-NoDerics 3.0 Unported License.

Image: “Lana Turner”

Url: http://www.flickr.com/photos/x-ray_delta_one

Access Date: 21 October 2015

License: Creative Commons Share Alike