You play and feel your way by ear and eye. But always you have

hindsights, if not insights

–Larry Eigner, “Qs & As (?) Large and Small”1

There are many definitions of ecopoetry and ecopoetics, but none quite fit Larry Eigner’s work.2 John Kinsella goes so far as to say that he has “grave doubts that an ‘ecopoetics’ can be anything but personal.”3 If this is so, then Eigner’s personal ecopoetics could be called his ecrippoetics, as I propose. The ungainliness of the term marks the intersection of the poet’s physical abilities, writing technology, and ecological crisis. As a person with disabilities whose activism focuses on environmental issues, Eigner’s use of a manual typewriter “crips” ecopoetics and “ecologizes” disability poetics. Eigner rarely mentions his disability in his poems, but it is from such a disability perspective that his interest in experimental poetics and concern for ecology emerge, and the defamiliar body is the locus at which these approaches to poetry – eco/crip – merge into Eigner’s idiosyncratic ecrippoetics. Eigner’s disability informs his practice of shaping a “material page,” but it does not determine how he writes or what he chooses to write about. Because he plays and feels his way “by ear and eye,” Eigner’s ecrippoetics makes poems that are rich both in visual and aural texture. It is what Timothy Morton’s deconstructive ecocriticism calls an “ambient poetics,” which “reflects the significance of multi-media in general, and synesthesia in particular.”4 The relationship between eye and ear, writing and speaking, necessarily involves space and time, and dividing eye from ear distinguishes what language in different mediums does in terms of space and time: graphic marks on a surface spatialize language and make it visible; articulated utterances happen in time and are invisible. “Ambience,” Morton observes, “denotes a sense of circumambient, or surrounding, world. It suggests something material and physical, though somewhat intangible, as if space itself had a material aspect.”5 Eigner’s ecrippoetics give space a material aspect by creating a visual form, and that visual form, in turn, corresponds to an aural performance of voice in time. Because it presents an ecological content and produces an ecological form, Eigner’s mixed-media poetry is the prime example of a poetry that thinks Morton’s “ecological thought” in which inside and outside, content and form, foreground and background, ear and eye, voice and image come into an uncanny juxtaposition on the page and in the world.6

Eigner’s ecrippoetics thinks the ecological thought, which can be defined as open and unending interconnectedness, by producing defamiliar textual bodies. Michael Davidson guardedly introduces the idea of the “defamiliar body” in the afterword to Concerto for the Left Hand: Disability and the Defamiliar Body. He is wary of reproducing the ableist tendency to see “proper” embodiment as conforming to a “normate” body, “but,” he writes, “as much as the aesthetic is underwritten by an able body, so it is revised when the photographer is blind, the poet is deaf, the pianist has one arm. The defamiliarization of the normate body is also the generative force in new cultural production.”7 Davidson argues for a disability poetics that complements a disability politics, a poetics that would allow for this new cultural production to register. Davidson describes Eigner’s compositional practice:

Eigner used his limited mobility to create a highly idiosyncratic pattern of lineation. . . . his lines tend to slant gradually across the page, each line indented a few spaces further toward the right to indicate the onrushing force of his perceptual awareness as well as his physical difficulty in returning the carriage to the left margin. Because his typing was limited to his right index finger, he painstakingly measured each word and phrase, often isolating individual words on a single line or using the space bar to mark changes of attention. And in order to avoid having to put a new piece of paper into the typewriter, he often continued the poem in the space vacated by his rightward tending lines. In short, Eigner’s material page became a cognitive map of his relationship to space, phenomena, and physiology.8

In this account, Eigner’s typing oscillates between intention and chance, control and contingency, deliberation and serendipity.9 The spacing and indentations depend on the limits of his abilities, but they are also “painstakingly measured.” His ability to type with only one finger slows the speed at which he can capture “onrushing” perceptions, but that pace also allows for sensitively marking shifts and changes inside and outside the poet’s mind. When Eigner shapes his “material page” into a “cognitive map,” he “defamiliarizes not only language but the body normalized within language.”10 Eigner’s friend, fellow poet, and editor Robert Grenier emphasizes that Eigner is “not ‘handicapped’” but, rather, “empowered by his / ability” to type and “shape the page.”11

Because Eigner developed his poetics on a manual typewriter – he could write, but his handwriting is barely legible – the shape of his poems on the page is determined by the interaction of his intentions as an artist and his body’s ability to control the typewriter, as we saw in Davidson’s account. Just as his experience in the external world is mediated by the prosthesis of his wheelchair, his experience in language is mediated by the prosthesis of the typewriter. Discovering this parallel, Eigner once remarked, “The typewriter is the only machine controls I am familiar with, except for the control stick on the electric wheelchair. Ah!”12 The typewriter ambiguously records both Eigner’s disability (partial returns of the carriage, mistrikes on the keyboard, irregular spacing) and his intentional choices (where the poem begins on the page, groupings of lines, nonlinear arrangement of text). Such elements create the distinctive shape on the page as Davidson describes; therefore, Eigner’s ecrippoetics produces what Jacques Derrida calls an “irreducibly graphic text,” one that achieves “its ‘modernity’” by exposing the “purely graphic stratum within the structure of the literary text.”13 For Derrida, modernism’s textual materiality is the first successful challenge to the metaphysics of presence because it scrambles the logocentric distinction between speech and writing, invisible and visible, inside and outside: “This is the meaning of the work of Fenollosa whose influence upon Ezra Pound and his poetics is well-known: this irreducibly graphic poetics was, with that of Mallarmé, the first break in the most entrenched Western tradition.”14

Editors and publishers of Eigner’s poetry are well aware of this tradition. In “The Text as an Image of Itself,” Curtis Faville, one of the editors of The Collected Poems of Larry Eigner, points out that Eigner’s typographical play follows in the line of “early modern departures from the traditional presentation of distributed text formalities [such as] Mallarmé’s Un Coup de Des.”15 Faville also sees Eigner’s typewriter as “the key ‘prosthetic’ link between Larry’s disabled body and the universe of print media,” but, in claiming that Eigner’s texts are images of themselves, Faville runs into some trouble with his terms.16 Clarifying what it is we are seeing or hearing when we read or listen to an Eigner poem will help us understand this visual component of his ecrippoetics and how it relates to his defamiliar body. Faville begins, “Historically, the content of a text has generally been considered as having a separate existence from its physical manifestation as print. . . . [T]he spoken word . . . was long thought to precede, or lie outside the parameters of the physical text.”17 The first problem is that a spoken word is also a “physical text,” it’s just not a mark on a surface. Textual editing provides many more terms for the interaction of intangible language with its material manifestations, and Jerome McGann makes a useful distinction between a written text’s “linguistic code” and its “bibliographic code”; the former being what the words mean linguistically and the latter being the material history and context of the text’s physical form.18 In Eigner’s work, along with other exceptions such as Mallarmé, Dickinson, or Cummings, the significance of the bibliographic code is greater than in other poets. Faville’s collapsing of “a text” into “the physical text” is confusing because all texts are found in physical documents. Using the terms according to the methods of textual editing, however, makes a clearer distinction. A text is a particular arrangement of marks on a surface that represents a work of art. Poems are not texts in this sense, but works that are, or can be, represented by a variety of texts (as well as in a variety of media, such as printed matter or recorded sound). We find those texts in documents – physical containers that hold the text. None of these are the work. Faville’s gambit is to reduce everything to text in order to confirm the “irreducibleness” of Eigner’s graphic form, but unless we destroy every other version of an Eigner poem aside from the “‘established texts’” that are the basis for The Collected Poems of Larry Eigner, a text cannot be an image of itself.19 It is a copy of a copy of a copy, ad infinitum.

Peter Schillingsburg, using terms parallel to McGann’s, emphasizes the importance of documents as intermediaries between the linguistic and bibliographic codes:

It will be useful . . . to have a term for the union of Linguistic Text and Document. I call it the Material Text. It seems clear that a reader reacts not just to the Linguistic Text when reading but to the Material Text, though it be subconsciously, taking in impressions about paper and ink quality, typographic design, size, weight, and length of document, and style and quality of binding, and perhaps from all these together some sense of authority or integrity (or lack thereof) for the text. These aspects of the Material Text carry indications of date and origin, and social and economic provenance and status, which can influence the reader’s understanding of and reaction to the Linguistic Text.20

The “indications” conveyed by the material text (I will drop Schillingsburg’s capitals) made by Eigner’s typing are the indexes to his disability, among other things. Therefore, it is Eigner’s material texts that defamiliarize language by being “irreducibly graphic texts,” and it is his defamiliar body that makes the linguistic text’s relationship with the documents it is found in also irreducible.

In other words, the material text is the work’s defamiliar body. Normate bodies and normate texts attempt to make their material instantiations invisible, transparent; as Lennard Davis observes, disability can be defined as a “disruption in the visual, auditory, or perceptual field.”21 A linguistic text can be invisible in a significant sense – we can memorize and recite a poem’s linguistic text, it is still physical in that it is made of synapses and sound waves, just not visible. It is easier for a visually impaired person, for example, to interact with a written work’s linguistic text rather than its material text; but, a material text, such as one rendered in Braille, is physically available (i.e., readable) to a visually impaired reader, it’s just not visible. Reading an Eigner poem out loud liberates its linguistic text from its visual material text, despatializing it, making it purely linear. An Eigner poem printed in Braille would preserve its spatial aspect, but can we say that this material text is an image of itself?

Some readers and critics propose that the material text constituted by sound is the better way to experience the embodiment of an Eigner poem. Stephen Ratcliffe considers Eigner’s poems to be equivalent to musical scores that “represent in notational form the sounds of a voice that otherwise would not be heard.”22 In Bodies on the Line, Raphael Allison proposes that a recording of Eigner’s actual voice indicates how he “crips” the lyric. Turning the tables on critics who fetishize what Eigner once wryly called his “momentous layouts,” Allison argues that “the repeated and uniform emphasis on Eigner’s graphic aesthetic erases his physical self.”23 As in Faville’s formulation, however, the term “physical” here is problematic. Certainly one’s “self” has a material basis in embodied perceptions and experiences, but the self and the body are not identical. Allison and Ratcliffe both claim that hearing a recording of Eigner reading aloud is the means by which we hear his authentic voice because it is marked by physical disability.

Ratcliffe writes, “To hear Eigner’s poems read aloud in his own voice (inaccessible to most listeners, those at least not used to his speaking habit) is to come face to face with the power of words to convey sense by sound (alone).”24 Allison privileges a recording of Eigner reading a poem over the printed poem because he finds that it “show[s] the awkward, lumbering, sometimes indecipherable, and error-prone voice sounding a language that it finds a challenge simply to express.”25 I believe that both critics intend to offer a way of acknowledging disability in Eigner’s work, but these statements strike me as just as ableist as saying that his typing is determined by his disability. They mean to accommodate Eigner’s manner of speaking, but what they are actually doing is reducing the meaning of his poems to disability.26 This is the tricky ground that I hope an idea of an ecrippoetics can help us navigate. A recording is a representation of Eigner’s voice; that is, it is a text, not the actual voice of the poet. The illusion that sound is the “natural,” physical link between language and its signs is at play here, and the logocentric privileging of speech over writing reinstates an ableist norm against which Eigner’s spoken words are measured.

In Allison’s account, Eigner’s vocal performance of a poem clarifies and corrects his ambiguous syntax and ellipses on the page through intonation and pacing as he reads the lines. The meaning is derived from normalizing and stabilizing the visual text.27 Relying on his notion of Eigner’s poems as scores, Ratcliffe locates meaning (“sense”) in sound itself: “if one cannot ‘understand’ Eigner speaking his poems – cannot make out what the words are – one nonetheless hears what is essential: pace, tone, pitch, pause, silence read (pronounced) according to the poem’s (page’s) direction.”28 Eigner himself is skeptical of claims such as Ratcliffe’s: “It’s fairly incredible to me that the only thing to be had from a piece of writing is sound.”29 Both Allison and Ratcliffe treat Eigner’s actual voice as a generator of meaning whether or not meaning is intended. But sound and voice are not the same thing, as Eigner himself recognized in an early poem that ends: “After trying my animal noise / i break out with a man’s cry.”30 Sound without meaning is an “animal noise”; the subject must “break” from that noise to make his complaint about the world not just sensible, but to make it make “sense.”

The poem as musical score is a standard trope for projectivist poets; it is based on Charles Olson’s claim that the typewriter, for a poet, is “the stave and the bar a musician has had,” and that modernist poets were using “the machine as a scoring to [their] composing, as a script to its vocalization.”31 Ratcliffe, however, goes further by equating the score with the poem (indeed, his essay is titled “Eigner’s ‘Scores’”), compounding the confusion between texts and works. Can poems be scores? Again, textual editing can help here. In “The Textual Criticism of Visual and Aural Works,” G. Thomas Tanselle writes:

The points that can be made about the nature of verbal works are directly applicable to thinking about music, even though the medium of music, sound, is less enigmatic than the ontology of language. What is immediately comparable about the two is that in each case the notation present on paper provides instruction for some kind of performance and is not in itself . . . part of the work of art. . . . Another similarity between musical scores and verbal texts on paper is that each can be the basis for a silent performance as well as a rendition out loud. Many people are adept at “hearing” music by reading scores, though when they do so, they are not experiencing the work in the medium in which its creator intended it to be experienced (unlike the silent readers of verbal texts). No two performances, silent or aloud, can ever be precisely identical, for the most that a score (like a tangible verbal text) can do is to provide a framework that encompasses, and delimits, a variety of performances.32

So, in Ratcliffe’s model, each reading of the poem, silently or out loud, is the poem (work) and the text is the notation for its performance. Yet, Eigner’s material page is intentionally “part of the work of art,” it is not merely notation for performance, so it is not exactly a musical score.

Tanselle acknowledges that both verbal texts and musical scores can have visual elements, that such texts or scores should be considered works of mixed-media, and the degree to which these visual features add to meaning would depend on the author’s intention. Therefore, it is best to think of Eigner as a mixed-media poet, in this case, because he has chosen (and not chosen) to add a visual component to his verbal texts. As Tanselle points out, most authors expect their readers to “hear” the verbal text silently. Eigner likely had this expectation as well, as indicated in this poem from the 1970s:

interior

speech,

thought

sweet and

silent33

Although Allison’s intention is to show us how Eigner crips the lyric, insisting that the slurred and hesitant enunciation heard on the tape is the real voice of disability seems to me to deny the voice Eigner hears in his head, which is “sweet and / silent,” and just as real. “Interior / speech” is, in fact, one of Eigner’s definitions of poetry: “Thought voiced and/or in the mind.”34

The ultimate cripping of speech, and the lyric’s association with it, would be to reveal its status as writing – Derrida’s arche-writing crips speech by demonstrating its dependence on an excluded, abandoned, and inauthentic other.35 Recorded readings will always be undermined by the supplement of the graphic text for the very reasons that Plato and Rousseau condemn writing: we ascribe a physical permanence to the mark, which risks the death of living speech by embedding it in lifeless matter. It is odd for Allison to argue against prostheses in regard to a poet like Eigner, but he claims that the tape recording presents the poet’s voice with “no mediating apparatus.”36 If we are being rigorously materialist about this, we have to acknowledge that we are not hearing Eigner’s living speech unmediated; we are hearing a representation of that speech as it was marked on magnetic tape and, later, transferred to a binary MP3 file. If there is a “voice of the body” in a text, it is a defamiliar body that makes us hear what we can see and see what we can hear.37

Eigner looked to the visual texts of other poets for models for his own practice. In a 1985 essay, he compares the standardized and edited versions of Emily Dickinson’s poems as they were first published with the Thomas Johnson edition of The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, which attempts to reproduce the poems more closely to the poet’s manuscripts. In a note, Eigner wonders:

As to her use of dashes, varying in length (not apparent from the books)–and there are her ways with capitals too–could Dickinson have possibly been careless more or less? How regular was her handwriting? Was Gerard Manley Hopkins a contemporary of hers, before the advent of the typewriter, or anyway the realization and use of its potential, who’s known to have come up with a calligraphic system graphing more specifically, accurately, how to speak a piece (in the mind)?38

These are similar to the questions evoked by Eigner’s ecrippoetics – what is deliberate or intentional? What is the consequence of carelessness, disability, or serendipity? Eigner wonders, was Dickinson using her idiosyncratic punctuation and orthography as scoring devices for performance? Is Hopkins’s diacritical system of accents marking his sprung rhythm comparable to Cummings’s and Olson’s use of the typewriter as a substitute for metrical patterning? Later in the same essay, he considers the musical score as well: “You wonder how versatile musical scoring has gotten or could be” (Areas 150). Rather than a visual musical score, however, Eigner more often used another model of producing irreducibly graphic texts as a metaphor for his practice.

Eigner imagines a relationship between his use of the typewriter and calligraphy, confirming his sense that his poems must be seen on the page to understand how they are to be voiced and heard. He coined a phrase for it in a poem:

calligraphy

typewriters

my hat

(bureau)

the world

inside

spins39

If the calligrapher’s brush is a prosthetic extension that allows her to mark the body’s voice in black lines on white space, then Eigner’s use of the typewriter is what allows him to do the same. The paradox is that we can only hear the voice of the body in our minds but we can see it on the page. If, in suppressing Eigner’s visual text in favor of his oral performance, Allison untypes his typing, then he also denies us access to the gestures of form in the poem in favor of unitary meaning. So, Eigner’s defamiliar body led him to develop a visual, graphic shape to his poems that he considered calligraphic, but in what way does calligraphy – the form or shape of letters and words – contribute to a text’s meaning?

In the essay that inaugurated the academic study of Eigner’s poetry, Barrett Watten uses structuralist linguistics and Russian formalism to find the “formal meaning” in Eigner’s syntax. Watten worked closely with Eigner as an editor in the 1970s, publishing his poems in the little magazine This, which he initially edited with Robert Grenier, as well as helping Eigner assemble a collection of his prose writings, so he is familiar with Eigner’s material texts.40 In his essay “Missing X,” however, he provides a deep analysis of the linguistic code of an Eigner poem rather than its bibliographic code. Wattten does not neglect the visual layout of the poem, nor does he ignore its “nonformal” meaning (i.e., what it is about), but his main concern is to account for how Eigner creates meaning through manipulation of syntax and grammar, suppressing predicates and emphasizing subjects. One of Eigner’s key techniques is ellipsis, leaving things out of the poem both grammatically as well as referentially, and this supports Watten’s idea of “the missing X” in Eigner’s poetry. He writes, “This X could be located in each case outside the poem,” yet, “at the same time, X could be” one part of the poem in relation to another part of the poem. The X could also be “the non-infrequent location of an apposed subject element on an axis horizontal to the body of the poem.”41 The missing X is a central feature of Eigner’s ecrippoetics because it frustrates any distinction between the inside and the outside of a text. Thinking the ecological thought, which entails “a radical openness to everything,” means that “inside-outside distinctions break down.”42 Davidson, again with some hesitation, adapts Watten’s figure for his interest in Eigner’s disability poetics: “I want to extend Watten’s useful speculations about predication to describe the ways that the ‘missing X’ could also refer to an unstated physical condition that organizes all responses to a present world.”43 For Davidson, in other words, Eigner’s missing X is disability or the defamiliar body.

Therefore, Eigner’s material page is the intersection of a poem’s “formal meaning” as he perceives and thinks about the world in and through his defamiliar body, and any of these things can be the missing X. For Watten, “the unity is in grammar, not objects, though there are ‘things’ in the poem.”44 For Davidson, the point is not to reduce the meaning of Eigner’s poems to disability, “not simply to find disability references[,] but to see the ways Eigner’s work unseats normalizing discourses of embodiment.”45 For both critics, Eigner’s work is a defamiliarization of norms, either in language or embodiment. Getting close to Faville’s “text as image of itself,” Watten writes, “the illocutionary act of the poem is the poem, accounting for its own existence, set against all else, as Eigner says, ‘to find the weight of things.’”46 In leaving out propositional acts (referring, predicating), Eigner’s illocutionary acts (stating, questioning) stand on their own as objects, which is the goal of projective verse. According to Olson: “For a man’s problem, the moment he takes speech up in all its fullness, is to give his work his seriousness, a seriousness sufficient to cause the thing he makes to try to take its place alongside the things of nature. This is not easy.”47 This aspect of projective verse is also what makes it formally ecological. According to Morton: “Ecological art, and the ecological-ness of all art, isn’t just about something (trees, mountains, animals, pollution, and so forth). Ecological art is something, or maybe it does something.” The “ecological-ness” of an Eigner poem is its material page, but it can also be the voicing of that page in speech: “The shape of the stanzas and the length of the lines determine the way you appreciate the blank paper around them. Reading the poem aloud makes you aware of the shape and size of the space around you. . . . The poem organizes space. Seen like this, all texts–all artworks indeed–have an irreducibly ecological form.”48 Eigner’s ecrippoetics is the defamiliarization of the normative form that insists on a distinction between inside and outside, and rather than making meaning by relating the objects (“things”) in the poem to a subject, it locates meaning in the weight of things (“words”) on the page.

The idea of weighing things cited by Watten comes from this 1973 poem:

to find

the weight

of things

the fish

the air

support

the flower

in the earth

pot

the woods

the floors49

As Watten’s quotation implies, it is not hard to read this poem as a “metapoem,” a poem about poetics.50 Eigner declares his ars poetica: to discover what “things” mean without imposing that meaning upon them one can weigh them, find what it is that they support and what they are in turn supported by. Indeed, flowers need air and water to grow, whether they are outside (“in the earth” or in “the woods”) or inside ([in the] “pot” or on “the floor[]”), and each of these things reciprocally supports the other. The poem’s linguistic code is clear enough. The Collected Poems of Larry Eigner provides a glimpse into the poem’s bibliographic code because it contains two versions of this text: the poem as quoted above from volume three, and a facsimile of its typescript in volume four. The facsimile shows one of Eigner’s paratextual notes to the right of the poem, another missing X: “In an interview Anselm Hollo citing the Provencal for to make a poem, trobar, to find, sd maybe at that it’s finding thngs and putting them together.”51 The parascript, in this case, confirms the reading of the linguistic code, and the only significant difference between the facsimile and the “‘established text’” in volume three is that in the typescript the last word appears as “flo ors” with a penciled correction closing the gap in the middle.52

So, in this case, the material pages do not produce very different meanings. Eigner often reproduced poems in letters he was typing, so there are also other versions of this text in various archives. Writing to George Butterick in 1974, Eigner types the poem into the margin of the letter and tells him:

I got it on reading Anselm Hollo’s speculation in an interview, after he cited the Provencal trobar, that poetry is finding things and putting em together (and ma’s inviting me to regard a pot of geraniums the man upstrs had just brought her, she held in her locked hands), and for seven months forgot abt Dr. Williams’ imagination and invention. As I think I noted in comment for St. James Press’ Contemporary Poets a few months ago, anyway I observed poetry for me has become thinking, a poem a course of thinking (and, e.g., there’s Rbt Frost’s “The Figure A Poem Makes”), and sooner and sooner afterward a record or artifact of thought, while I’m pretty well incapable of long substantial poems. But, at that, how things go together or are put together is maybe pretty much of a piece with what import, aim, drift, vector, force, meaning, is discovered in them or given to them. Epistemology, oh well, and brdcast news!53

The broader context supplied by this version of the material text – the Williams-esque moment of his mother showing him the pot of flowers–indicates what Eigner means by privileging immediacy and force over clarity and communication. The force of the poem is the moment of realization that joins the pot of flowers to the idea of putting things together to find out what they mean, which Eigner has just learned is one definition of poetry. A different poet would perhaps provide some rhetorical framing to locate the scene and clarify meaning, but Eigner’s ecrippoetics work by compression and ellipsis. In his letter to Butterick, he admits that meaning may be “given” to things, but how we know what we know (“epistemology”) is a question, and sometimes we just learn things from the news.

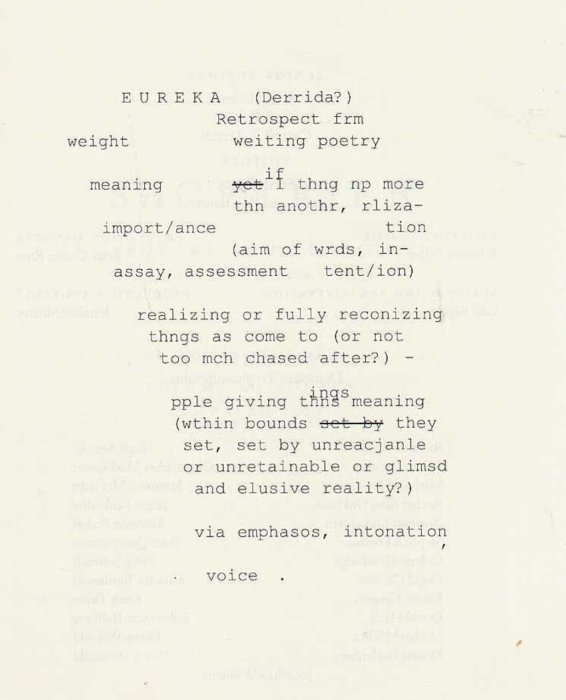

E U R E K A

weight

meaning

import/ance

assay, assessment

This poem is part of “an unpublished poetics statement by Larry Eigner typed on the back of an envelope postmarked 22 July 1987,” according to Benjamin Friedlander, who holds the document in his personal collection.54 I have extracted what I identify as the “poem” above – the entire statement reads:

Fig. 1: Unpublished poetics statement by Larry Eigner typed on the back of an envelope postmarked 22 July 1987. Courtesy of Benjamin Friedlander.

Even when it is transcribed, the text emphasizes its own materiality by following the diagonal flap of the envelope from the top left slanting to the bottom right. “Retrospect frm / weiting poetry” classifies this statement as one of Eigner’s hindsights that leads to insight. His typo functions as a Derridean metaplasm; the mistrike of “e” for “r” puts writing under erasure, and invokes the idea of weighing things to determine their value or meaning, or wei(gh)ting things to make them meaningful, and it also contains a Derridean deferral as a pun on “waiting.” It is a trace figure: there is an unnegotiable relationship between writing/waiting/weighting in this term. It is a mistake – certainly Eigner intended to strike r on his keyboard rather than e – that, being retained, becomes intentional and thereby signifies. The parenthetical statement that butts up against the poem, “(aim of wrds, in- / tent/ion)” can be paraphrased as words aimed at meaning, a great definition of “intention” (Eigner called an essay on poetics from the early 1970s “Arrowhead of Meaning”).

“E U R E K A” is what Morton would call “medial writing.” Although I can extract what appears to me to be the “poem” at the center of this arrangement, Eigner has made that move highly problematic by forcing the background (context, notes, explanations, mistakes, noise) into the foreground (text, statement, intention, meaning). “Medial writing” according to Morton, “highlights the page on which the words were written, or the graphics out which they were composed” because “ambient poetics seeks to undermine the normal distinction between background and foreground.”55 When everything is interconnected, we cannot draw clean lines between foreground and background, center and edge, inside and outside, intrinsic and extrinsic, text and context. Eigner himself wondered how much of the missing X to bring into the poem: “Distances between words are not negligible elements of a piece: pauses or silences. Punctuation can be intrinsic, as a title or heading can be, lacunae too can be, times when you (can) come up with such, ditto a parascript, and even a footnote has seemed nondistracting at least once.”56

When we see and read the material text we can hear the poet’s voice as he intended it to be heard rather than listening to a material text of his voice with its unintentional marks of disability. Meaning is found (or given) by the weighing of words through “emphasos, intontation / , / voice.” Morton refers to this as the “timbral voice,” which “far from the transcendental ‘Voice’ of Derridean theory . . . does not edit out its material embodiment.” He continues, “One of the strongest ambient effects is the rendering of this timbral voice. Our own body is one of the uncanniest phenomenon we could ever encounter. What is closest to home is also the strangest–the look and sound of our own throat.”57 Eigner’s material texts are the defamiliar body that is the return of the repressed, the unfamiliar that is familiar, the writing that we can hear and the speaking that we can see.

Morton, in part, derives his idea of the timbral from Derrida’s meditation on the tympanum, or inner ear. In “Tympan,” Derrida notes, “it has been observed, particularly in birds, that precision of hearing is in direct proportion to the obliqueness of the tympanum. The tympanum squints.”58 If the tympanum squints, the ear becomes an eye that hears. As well as being a “sideways glance,” a squint is “an oblique reference or inclination,” and to have an oblique inclination means “having a slanting or sloping direction,” which Eigner’s graphically irreducible poems, as we have seen, often do. In the text that occupies the margin of Derrida’s “Tympan,” a quotation from Michel Leiris’s Biffures, Leiris writes, “in the final analysis caverns [such as the ear] become the geometric place in which all are joined together . . . the matrix in which the voice is formed, the drum that each noise comes to strike with its wand of vibrating air.”59 Eigner’s first book was titled From the Sustaining Air, and air, atmosphere, wind, weather, sound, noise, broadcasts, and birdsong are the “constant ephemerals” that his material texts realize.60 Playing his poems by ear and eye all those years led Eigner to many hindsights and insights, which are to be found on his many material pages.

Larry Eigner, Areas Lights Heights: Selected Writings 1954-1989, ed. Benjamin Friedlander (Roof, 1989), 150. ↩

Recent studies of experimental ecopoetry that get close to accommodating a disability poetics like Eigner’s include Sarah Nolan’s Unnatural Ecopoetics: Unlikely Spaces in Contemporary Poetry (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2017), Lynn Keller’s Recomposing Ecopoetics: North American Poetry of the Self-Conscious Anthropocene (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2017), and David Farrier’s Anthropocene Poetics: Deep Time, Sacrifice Zones, and Extinction (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019). ↩

Forrest Gander and John Kinsella. Redstart: An Ecological Poetics (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2012), 37. ↩

Timothy Morton, Ecology without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007), 34. ↩

Morton, Ecology without Nature, 33. ↩

For another account of the development of Eigner’s ecopoetic form, see George Hart, “Walking the Walk: Ammons, Eigner, and Ecopoetic Form in the 1960s,” ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 24, no. 4 (2018): 680–706. ↩

Michael Davidson, Concerto for the Left Hand: Disability and the Defamiliar Body (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008), 226. ↩

Michael Davidson, “Disability Poetics,” The Oxford Handbook of Modern and Contemporary American Poetry, ed. Cary Nelson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 597; Davidson provides another account of Eigner’s use of the manual typewriter in Concerto for the Left Hand, 124-25. Once asked in an interview what the primary effect of his cerebral palsy was, Eigner replied, “I don’t know. Being jerky in my movements.” Contemporary Authors Autobiography Series 23, Gale Research, 56. ↩

Barrett Watten argues that Eigner should be considered a “distributed author” in that his authorial intentions are distributed among the other poets, friends, and editors who helped him make typescripts, select poems for collections, and arrange typesetting and printing. (“Scenes of Decision: Larry Eigner as a Distributed Author,” forthcoming in Momentous Inconclusions: The Life and Work of Larry Eigner, edited by Jennifer Bartlett and George Hart (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2020. ↩

Davidson, Concerto, 118. ↩

Quoted in Stephen Ratcliffe, Listening to Reading (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2000), 121. ↩

“Twenty-one Poems and an Interview.” The Kaleidoscope, spring 1982, 13. ↩

Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, 40th Anniversary Edition (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), 64. ↩

Derrida, Of Grammatology, 99–100. ↩

Larry Eigner, The Collected Poems of Larry Eigner, ed. Curtis Faville and Robert Grenier (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2010), vol. 4, xxviii. ↩

Eigner, Collected Poems, vol. 4, xxxii. ↩

Eigner, Collected Poems, vol. 4, xxvii. ↩

Jerome McGann, The Textual Condition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), 60. ↩

“‘Established texts’” is the editors’ phrase for texts based on typescripts prepared by Eigner with the help of Robert Grenier (Eigner, Collected Poems, vol. 1, xiv). ↩

Peter L. Shillingsburg, “Text as Matter, Concept, and Action,” Studies in Bibliography 44 (1991): 54. ↩

Lennard Davis, from Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness and the Body. The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 3rd edition (New York: Norton, 2018), 2175. ↩

Stephen Ratcliffe, Listening to Reading (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2000), 155. ↩

Raphael Allison, Bodies on the Line: Performance and the Sixties Poetry Reading (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2014), 174. Eigner uses the phrase “momentous layouts” in a letter to Charles Bernstein (Charles Bernstein Papers, Special Collections and Archives, UC San Diego). ↩

Ratcliffe, Listening to Reading, 155, emphases in original. ↩

Allison, Bodies on the Line, 185. ↩

This is a fraught issue. Eigner’s family encouraged him to speak and write clearly so that he could be understood. In “Course Matter,” recounting a recovery from an injury he suffered from a wheelchair accident, Eigner says he was still getting “speech therapy” that “brother and s..-in-law got me to take […] as I was talking strenuously enough as yet, often enough, hence poorly, words coming out skewed” (Areas 141). ↩

Allison, Bodies on the Line, 188. ↩

Ratcliffe, Listening to Reading, 155. ↩

Larry Eigner, Areas Lights Heights, 121. ↩

Eigner, Collected Poems, vol. 1: 140. ↩

Charles Olson, “Projective Verse,” in The Collected Prose of Charles Olson, eds. Donald Allen and Benjamin Friedlander (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 245. ↩

G. Thomas Tanselle, “The Textual Criticism of Visual and Aural Works,” Studies in Bibliography 57 (2005–6), 5–6. ↩

Eigner, Collected Poems, vol. 3, 1326. ↩

Eigner, Areas Lights Heights, 47. ↩

Allison actually confirms Derrida’s arche-writing. He reports that he was unable to find a “textual basis” for two of the poems, but why should that matter when he is concerned with the audio-recorded texts that he has at hand (183)? In any case, The Collected Poems of Larry Eigner indexes the poems by titles and first lines, so the mislabeled “Tribute to Cage,” which begins “living / music,” can be found on page 1192 of volume three, and the mislabeled “At Death, Olson’s,” which begins “get a / hand-out,” can be found on page 936. Whoever created the track list for the cassette mistook Eigner’s paratextual notes for titles. Moreover, the fact that Allison needs to track down the “textual basis” for audio recordings confirms the Derridean assertion that writing precedes speech–he requires the visual texts as counterpoints to his audio texts, and if the spoken text corrects the written text then writing must come first. ↩

Allison, Bodies on the Line, 183. Shillingsburg observes that “any recitation, whether from memory or from a written text, is a new production of the text susceptible to ‘transmission error’ or embellishment,” 55, n. 29. ↩

The phrase “voice of the body” is David Hinton’s. In The Wilds of Poetry, he traces the ecopoetic tradition back to Whitman, who, he claims, “reinvented language as the voice of the body” (16). Sixteen poems by Eigner are included in Hinton’s anthology. David Hinton, editor, The Wilds of Poetry: Adventures in Mind and Landscape (Boston: Shambhala, 2017). ↩

Eigner, Areas Lights Heights, 55. ↩

Eigner, Collected Poems, vol. 4, 1359. ↩

Larry Eigner, Country / Harbor / Quiet / Act / Around: Selected Prose, edited by Barrett Watten (THIS, 1978). ↩

Barrett Watten, Total Syntax (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1985), 178. ↩

Morton, The Ecological Thought (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010), 15, 36. ↩

Davidson, Concerto for the Left Hand, 122. ↩

Watten, Total Syntax, 180. ↩

Davidson, Concerto for the Left Hand, 121. ↩

Watten, Total Syntax, 190. ↩

Olson, “Projective Verse.” The Collected Prose of Charles Olson, 247. ↩

Morton, The Ecological Thought, 11. ↩

Eigner, Collected Poems, vol. 3, 1152. ↩

For an example of such a reading, see Hart, “Postmodernist Nature/Poetry: The Example of Larry Eigner,” in Reading Under the Sign of Nature: New Essays in Ecocriticism, eds. John Tallmadge and Henry Harrington (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2000), 124–26. ↩

Eigner, Collected Poems, vol. 4, p. 1726. ↩

The parascript is included in the notes, so even without the facsimile The Collected Poems includes this information. Eigner himself was ambivalent about when to include such information and when to leave it out: “If anything isn’t intrinsic, better to do without it, or sum up with something else. Immediacy and force take priority over notes clarifying allusions. A dedication ‘To So-and-So,’ for instance, doesn’t seem to interfere with a piece as much as I felt it did 15 or 20 years ago. Then, I felt less sure of my poems at the time of writing them and was aiming to write big and perfect poems” (Areas 149-50). ↩

Eigner to Butterick, 11/06/74; George Butterick Collection, The Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. ↩

An image of the envelope appeared on the cover of Sagetrieb, vol. 18, no.1, and Friedlander’s transcription is included in that issue. For Friedlander’s reflections on transcribing this text, see “Typos and Abbrevs,” https://nationalpoetryfoundation.wordpress.com/tag/larry-eigner/. 8 April 2010. ↩

Morton, Ecology without Nature, 37, 38. ↩

Eigner, Areas Lights Heights, 149. ↩

Morton, Ecology without Nature, 40. ↩

Jacques Derrida, Margins of Philosophy, trans. Alan Bass (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982), xv. ↩

Derrida, Margins of Philosophy, xix. ↩

The phrase “constant ephemerals” is from an early poem, Collected Poems of Larry Eigner, vol. 1, p. 76. From the Sustaining Air was published by Robert Creeley’s Divers Press in 1953. Jonathan Skinner discusses the wide variety of sounds that Eigner responded to in his “soundscape” and produced in his poems in “What Sounds: Larry Eigner’s Environments,” forthcoming in Momentous Inconclusions: The Life and Work of Larry Eigner, edited by Jennifer Bartlett and George Hart (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2020. ↩

Article: Author does not grant a Creative Commons license for this essay.

Image: "how th leevs in stanly park," by bill bissett (2020).