The paired qualities of contingency and dispersion inform the theoretical inflections of this page and shape the delivery of its content. The materials featured here extend a presentation given at the Approaching the Poetry Series Conference held at Concordia University on April 5, 2013. Over the course of the following essay, I consider two online collections that are likely to be well known to Amodern’s readers (PennSound and UbuWeb) alongside two sites that are likely to be lesser known (Mutant Sounds and SpokenWeb). This route is plotted to address SpokenWeb, but will only arrive at its destination by way of conclusion. Following this trajectory, I argue, a user might come to an understanding of SpokenWeb from within a wider culture of online collections. Along the way, the page gathers a compendium of already circulating objects via text, image, sound, and movie files. Just as someone might “read” a magazine exclusively for the pictures, I imagine someone might read this page exclusively for the downloads.1 My aim is to chart the passage of a specific constellation of materials through several little databases as a scenario for objects hosted by online collections in general. This page is constructed on the principles of selection, navigation, description, and distribution. The corresponding acts of interpretation, analysis, or critique may arise within the reader of these paragraphs and the objects embedded within them.

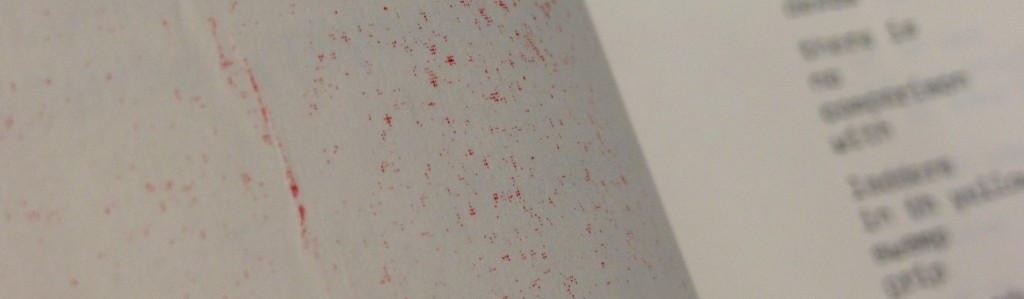

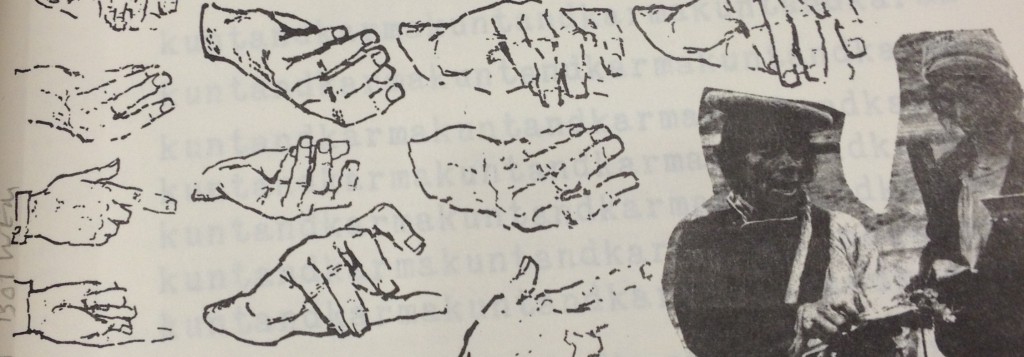

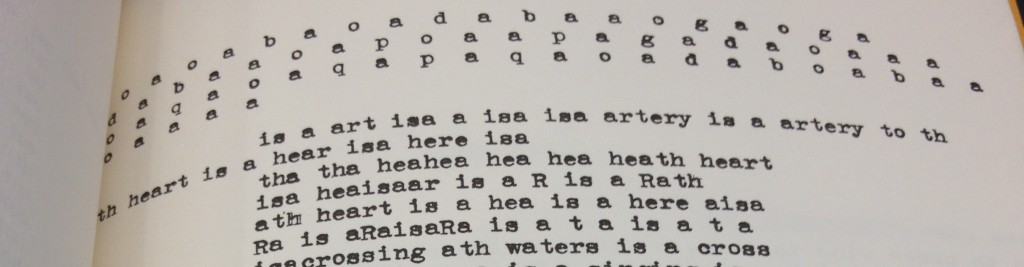

| JPG: | bill bissett, detail from the lost angel mining co. (Vancouver: Blewointmentpress, 1969) | |

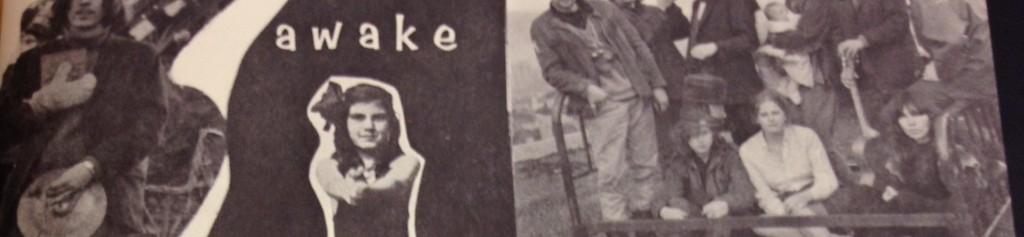

| MP3: | bill bissett & th mandan massacre, “2 awake in th red desert!!,” Awake in th Red Desert (Vancouver: See/Hear Records, 1968) | |

| Download: | bissett, “2 awake in th red desert,” Awake in th Red Desert (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1968) [JPG] |

To address the sites featured here, this essay follows the thread of a particular poet’s output in an attempt to tease out a description of each online collection, how they mediate the recordings they host, and how we might begin to understand contemporary iterations of the audio database through this network. For the moment, it does not particularly matter who the poet is, nor what the character of their output might be. I have chosen bill bissett for a number of incidental, autobiographical, and medial reasons that will be made clear throughout the essay. However, from the onset, I must insist that this essay could have just as easily followed any of a dozen other poets presented on a dozen alternate platforms. Simply put, it is useful to follow a thread. Not a special thread, as a symptomatic reading or work of cultural critique might have it, but any thread whatsoever. Ravelling a path through the database is perhaps all that a narrative format like the essay might attempt: in other words, the essay can be understood as a kind of test for trajectories through these networks. Alongside the essay, we might add archival downloads, edited compilations, a related scroll of images, sources, or hyperlinks. If there is anything to be learned from the sites I examine, it is that any webpage may also contain a collection. This page offers one such alternative to the little databases it samples.

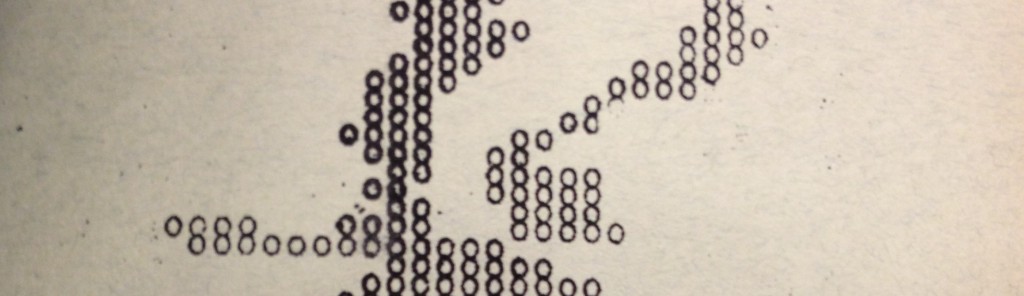

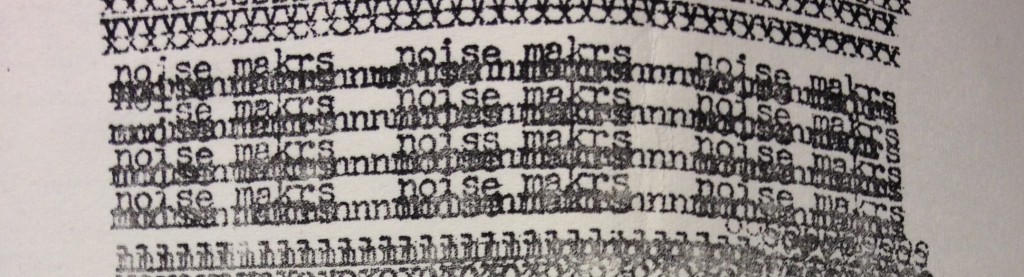

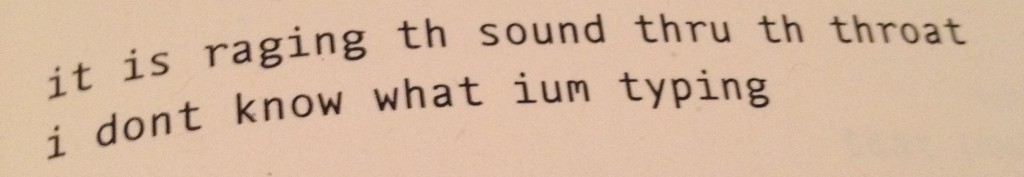

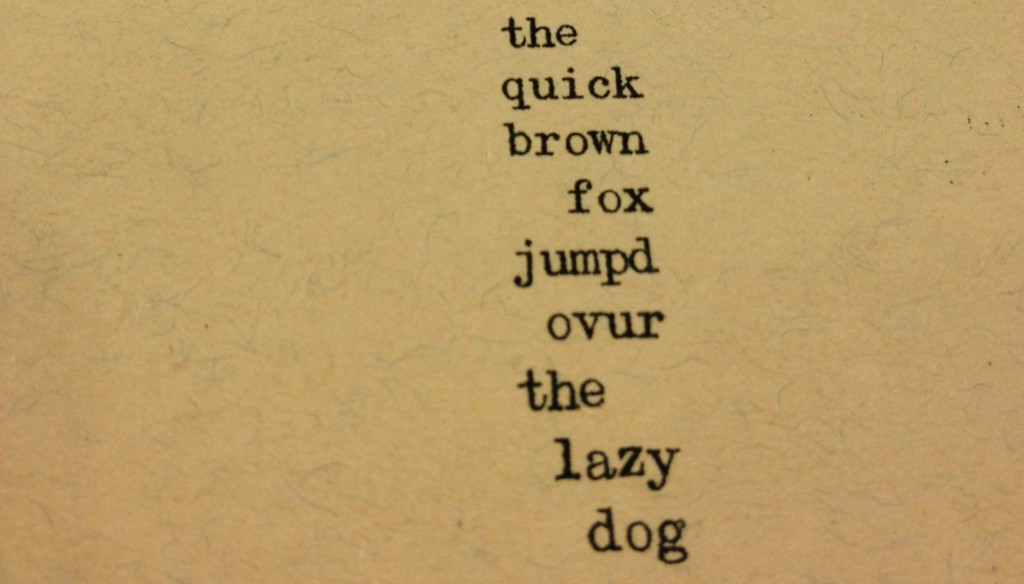

| JPG: | bissett, from words in th fire (Vancouver: Blewointment Press, 1972) | |

| MP3: | bissett, “Circles in th Sun” from lost angel mining company, Sir George Williams University reading (1969) | |

| Download: | Contemporary Literary Criticism, bissett entries [ZIP: PDF, 2.5MB] |

This particular foray into a network of bissett recordings is both informed by and inscribed within an ongoing research project into what I term the “little database.” I offer the analogical coding of these online distribution platforms as little databases after the little magazines that served as the vehicle of modernism and the historical avant-garde. This terminology is indebted to recent developments in periodical studies that Robert Scholes and Cliff Wulfman have described as a transition “from genre to database.”2 Inhabiting the vexed space between preservation and distribution, between memory and practice, these sites dramatically reconfigure the contemporary experience of historical artifacts. Far from a simple act of remediation or media conversion, the process of transcoding – broadly defined by Lev Manovich as the translation of culture from analog media to digital networks – presents a complex set of radical alterations to historical works.3 This new form of archive, more than simply degrading or distorting analog works of art and literature, dramatically rematerializes historical works for the use and reuse of millions of users. I argue that a reading of specific digital objects in coordination with their file formats (following studies of protocol and infrastructure by Alex Galloway and Jonathan Sterne) and local database contexts (following explorations in material texts and contingency by Lisa Gitelman and Alan Liu) might open an understanding of the historical works that circulate widely within the cultural and technical processes of the internet.4

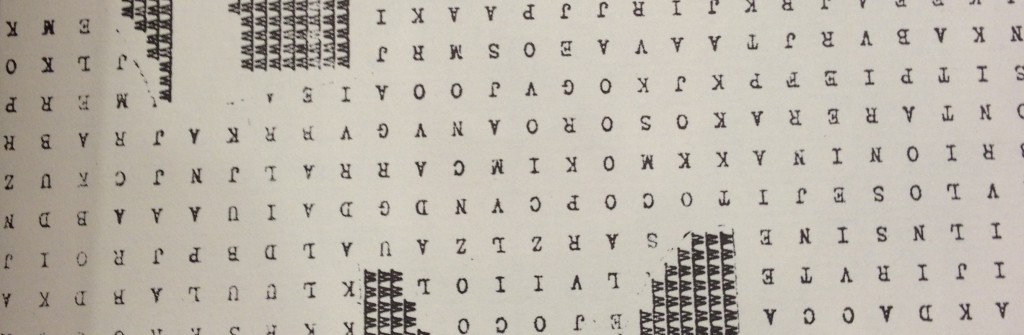

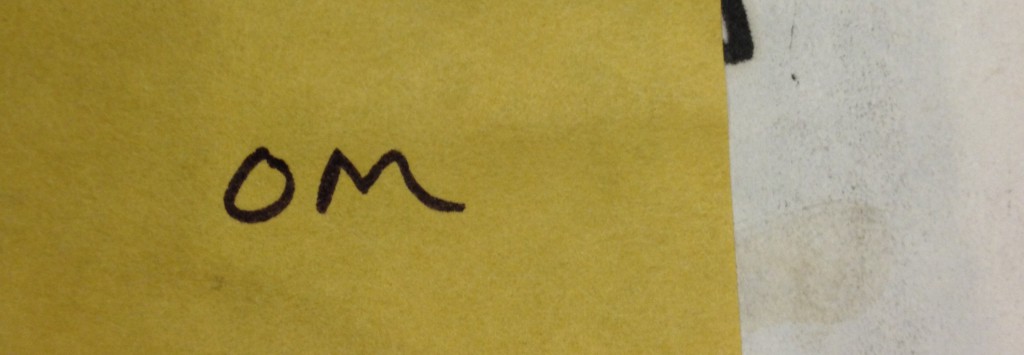

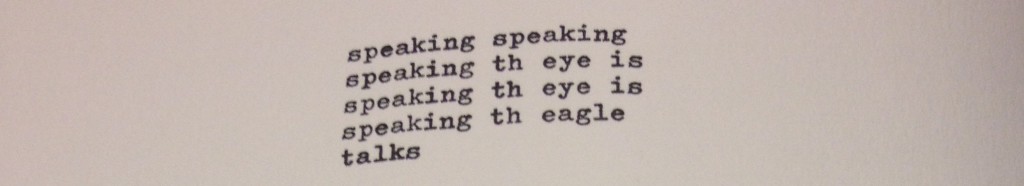

| JPG: | bissett, Medicine My Mouth’s on Fire (Ottawa: Oberon Press, 1974) | |

| MP3: | bissett, “Colours” (1966), Past Eroticism: Canadian Sound Poetry of the 1960s (Underwhich Audiographics No. 13, grOnk Final Series #6: 1986) | |

| Download: | Past Eroticism: Canadian Sound Poetry in the 1960s, UbuWeb [ZIP: MP3, 111MB] |

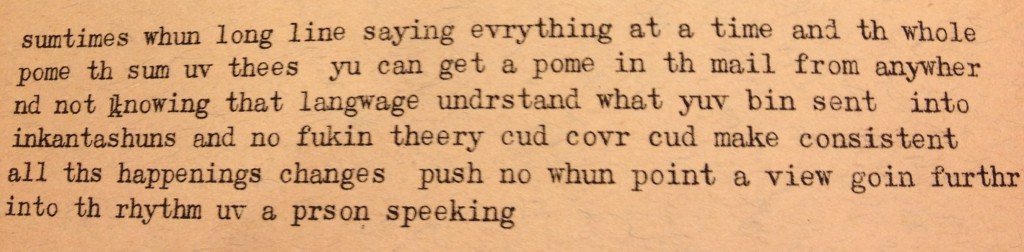

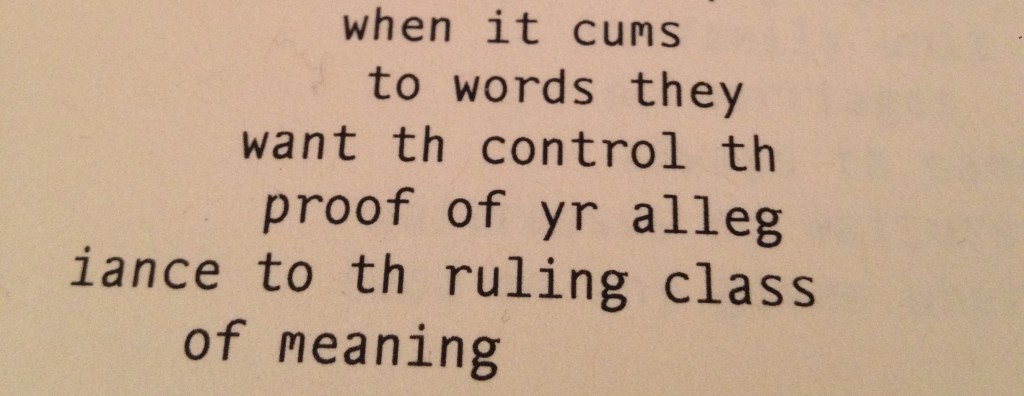

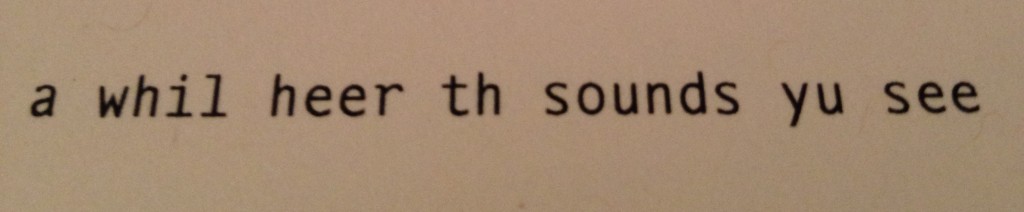

As a supplementary gesture in this direction, each paragraph on this page is interspersed with an image of a page from a book by bissett for potential close reading. This editorial premise is constrained to excerpts that relate to bissett’s poetics of recording and media in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Each image may be incorporated into the argument of this essay by the reader, however they may choose to do so. Further, an audio recording accompanies each image and paragraph, which may be heard in concert with both the images and the essay. If the internally standardized conventions of bibliography and performance in bissett’s output over the last thirty years have muted the urgency of his poetics, perhaps these archival materials can be released anew – in facsimile and recording, altered but indexed – as urgent documents for a rapidly changing media environment in the new century.5 Altogether, I have found that this expanded set of probes presents an argument for bissett as an important entry point into the study of digital remediation. The reader may find otherwise. My approach attempts to channel a mode of fidelity to the ways in which bissett’s early work, in the words of Darren Wershler, “defies conventional notions of genre: collages are paintings and drawings bleed into poems turn into scores for reading and chant and performance generates writing bound into books published sometimes or not.”6 As a kind of parasite on bissett’s web presence, the reader might consider this essay to be the introduction to a new set of versions of these objects as digital files. The lines between preservation and republication are increasingly difficult to define. We might not consider a book transformed based on the library or archive that contains it. However, if the same book were reprinted by a new press, its bibliographic codes would be widely recognized as significantly revised. As with the republication process, bissett’s output acquires new bibliographic codes in each of the following four sites of its reappearance. The little database, even masked as an essay, also suggests that a highly significant mode of versioning is taking place in every instance.

| JPG: | bissett, back cover detail from th wind up tongue (Vancouver: Blewointmentpress, 1976) |

|

| MP3: | bill bissett & th mandan massacre, “heard ya tellin,” Awake in th Red Desert (1968) | |

| Download: | Steve McCaffery and bpNichol, Sound Poetry: A Catalogue (Toronto: Underwich Editions, 1978) [PDF, 51MB] |

Mutant Sounds

The incident that generated this essay occurred six years ago when I stumbled upon a relatively unnoticed archival release through a little database called Mutant Sounds.7 In the heyday of the music blog, Mutant Sounds delivered an incredible array of rare and obscure albums, primarily ripped from out of print vinyl LPs, free for download. Founded in 2007, the Mutant Sounds blogspot had amassed over 3,000 posted releases in five years, many so rare that only the most devoted, and wealthiest, crate diggers might have ever heard their sounds. The reader might note that UbuWeb hosts just under 1,000 entries in the “sound” subsection of the site and PennSound features around 600 author entries. While these pages most often host multiple sets of recordings per entry, the volume is roughly comparable to the Mutant Sounds inventory. Given the cultural support and academic prominence of PennSound and UbuWeb, it’s all the more remarkable that Mutant Sounds – a free blog platform periodically releasing download links enabled by free filesharing servers – might rival these collections as one of the great distribution channels (or, more boldly, archival collections) for obscure experimental recordings from the last half-century. At least, it may have been recognized as such by its devoted core of users. However, these qualifications have become moot: the collection disappeared from the internet just as suddenly as it had once appeared.

| JPG: | bissett, “the caruso poem,” Awake in th Red Desert (1968) | |

| MP3: | bill bissett & th mandan massacre, “an ode to d a levy,” Awake in th Red Desert (1968) | |

| Download: | Radio program featuring bill bissett, Robert Creeley Tapes, PennSound (c. 1978) [MP3] |

In the spring of 2013, when I first delivered this inquiry at the Concordia conference, the website had just ceased operations. After six years of reissuing out of print albums on a (slightly misinformed) “notice-and-takedown” principle of online copyright law, a greater current led by the RIAA and the scandalous failure of MegaUpload brought about the site’s demise. RapidShare, the file locker of choice for Mutant Sounds, had deleted most files that the site had uploaded to its server in an effort to avoid the same fate as Kim Dotcom.8 This process was accelerated by the emergence of a range of streaming platforms, from Pandora to Spotify, as well as a few musicians devoted to dismantling the site. Currently, the Mutant Sounds catalog of thousands of painstakingly digitized recordings lies in the obscurity of digital ruin. The site proves two important points that UbuWeb founder Kenneth Goldsmith has often repeated over the last ten years: first, that anyone could have made such a collection given the abundance of free resources and relative internet neutrality of the past two decades; and second, that on any given day it could all simply disappear.9 We might add two more points: one, that this type of collection is increasingly unlikely to appear; and two, that the DIY internet of the nineties and aughts is quickly disappearing.

| JPG: | bissett, from RUSH: what fuckan theory: a study uv language (Toronto: Gronk Press, 1971 / BookThug, 2012) | |

| MP3: | bill bissett & th mandan massacre, “is yr car too soft for th roads,” Awake in th Red Desert (1968) | |

| Download: | Maurice Embra, Strange Gray Day This, bill bissett documentary (1964) [ZIP: MP4, 110MB] |

In a roundtable hosted by The Awl aptly titled “The Rise and Fall of the Obscure Music Download Blog,” Mutant Sounds editor Eric Lumbleau addresses the unique moment of these ‘sharity’ sites, active primarily from 2004 until 2012.10 Summarizing the purpose of the Mutant Sounds collection for the Free Music Archive, the editors characterize their project as a campaign for “enlightening the masses to elusive musical esoterica buried beneath canned historical narratives and induced cultural amnesia.”11 The ideological thrust of the collection – much like UbuWeb and PennSound – was to destabilize the historical narrative by distributing an alternate canon far and wide. In particular, Mutant Sounds was plotted to combat the accepted progression from rock to punk to post punk. A brief stroll through their posts quickly presents a much stranger and far more diverse sense of experimental music from the mid-sixties to the present. Or rather, one might hear that argument if the collection were still intact. Instead, today’s user will find only the contexts, descriptions, and images of albums one might never find elsewhere. Perhaps these remnants of the site may still function like the Nurse With Wound list that guided the collection itself: as a series of signposts for further exploration.12 In the enclosed ZIP file, the reader may download the complete remnants of the site.

| JPG: | bissett, from s th story i to: trew adventure (Vancouver: Blewointmentpress, 1970) | |

| MP3: | bill bissett & th mandan massacre, “she still and curling,” Awake in th Red Desert (1968) | |

| Download: | Mutant Sounds HTML Archive (2014) [ZIP: HTML, 140MB] |

Within this catalogue, on February 1st, 2008, Mutant Sounds released a digital version of the incomparable album, Awake in th Red Desert, recorded by bill bissett and th Mandan Massacre in 1968. At the time, I ran a pseudo-anonymous blog in between audio engineering sessions for PennSound, where I had recently become an editor. I downloaded the album immediately, as part of a habitual requisition session among the various music blogs I followed. Before the “filter bubble” of social media encapsulated the navigable internet, these sessions were a mode of discovery within an enigmatic and unpredictable network. Like many of the untold numbers of collectors exploiting the releases shared by Mutant Sounds, my private collection grew within the contours of my own interests. Unlike the stable collections of PennSound, UbuWeb, or SpokenWeb, these releases came to exist only as a dispersed set of objects on hard drives accumulating diverse sets of materials in unknowable configurations. In my own collection, Awake in th Red Desert arrived as a RAR archive file. The decompressed folder was saved to my general “Music Library” folder and the RAR file was discarded. Duplicate copies of the album were placed in two adjacent folders: the first, for potential upload to PennSound; the second, in a database structured for the collaborative Endless Nameless project I published with James Hoff at the time. Endless Nameless organized digital objects by their original publishers to produce a series of limited edition hard drives. In this instance, I made a new folder entitled “See/Hear Records.” I rechart this activity as it is quickly disappearing in an era of cloud listening and authorized in-application purchases.13 The provenance of other iterations, within other users’ collections, is as variable as the unknown numbers of downloaders.

| JPG: | bissett, from words in th fire (1972) | |

| MP3: | bill bissett & th mandan massacre, “now according to paragraph C,” Awake in th Red Desert (1968) | |

| Download: | bill bissett and th mandan massacre, Awake in th Red Desert (1968) [ZIP: MP3, 69MB] |

With each new posting to Mutant Sounds, the editors wrote a short text. The release comments accompanying bissett’s record bear reiterating in full:14

Originally released circa 1968 in an edition of 500 copies, the lunacy contained within the grooves of this Canadian mindfuck is perched somewhere midway between the outwardly bound trajectories of their contemporaries in both The Nihilist Spasm Band and Intersystems, with intuitive and screw-loose outsider psych improv moves crashing headlong into lividly blurted sound poetry in a way that also calls to mind the touched-in-the-head maneuvers of Fire & Ice, Ltd (not to mention a raft of contempo freak folk practitioners…). Bissett is far better known as a poet (phonetische and otherwise) than musician and his spew here is what really tugs this in the direction of the aforementioned head cases in Intersystems. This is taken from the out of print CD reissue of several years back and features three 90’s era bonus cuts by Bissett and some other character that are both gruesomely awful and woefully out of place in this context, though that said, this CD sounds a good bit better than my rather battered original vinyl…

The post fits the generic conventions of the Mutant Sounds approach to distribution. Locating bissett within the context of the site’s postings devoted to “screw-loose outsider psych improv,” jangly electronic post-punk, and damaged noise albums, every post is related to the collection as a whole. The text bespeaks the importance that Mutant Sounds placed in its well-earned outsider status, as one of the most extreme sources for historical records online. The collection is rewritten with each new relational text. Not only in synchronic relation to Canadian experimental music (The Nihilist Spasm Band and Intersystems), but also to a wide range of albums hosted on the site. Much could be gathered today, for example, by plugging these references into a topic-modeling network diagram. Of course, the position of the album as charted by Mutant Sounds produces a dramatically different register than the presses with which and poets with whom even this recorded work is most often associated. Nevertheless, with bibliographic attention to release dates, edition numbers, and the technical process of the digitization, the text transmits the essential components of archival metadata.

| JPG: | bissett, detail from Awake in th Red Desert (1968) | |

| MP3: | bill bissett & th mandan massacre, “fires in th tempul,” Awake in th Red Desert (1968) | |

| Download: | Free Music Archive, Bill Bissett: Pleonasm Mix (2010) [ZIP: MP3, 64MB] |

Aside from the adjacent domain of experimental music, one primary difference to the collections that follow is that Mutant Sounds exclusively presented download links to full albums for external use. I’ll return to this point in relation to the other sites discussed, but for now, we might sketch the general character of this distribution method. Each blog post was linked to a full album download. These downloads were typically delivered as RAR or ZIP files that compressed a folder containing individual tracks, along with extremely lo-fi images of album artwork. The archive was a conduit for personal use, with the emphasis exclusively placed on sound. In the case of Awake in th Red Desert, this meant the exclusion of the “recorded book” that was originally distributed with the album by See/Hear Records. In this way the fundamental purpose of the original publication – relating the printed page to the audio recording – has been excised from the digital release. This action is at the heart of the formlessness of the MP3. As Jonathan Sterne has noted: “at the psychoacoustic level as well as the industrial level, the MP3 is designed for promiscuity.”15 In other words, the sustained attention of “reading along” is counterintuitive for a format built for distracted listening and streamlined distribution. Recordings of poetry readings in the MP3, as we’ll see, in general present an alternative to these popular uses of music online. At any rate, after download, the MP3 files were at the user’s disposal in their own private collection, free to be used on any platform in any number of circumstances.

| JPG: | bissett, from the lost angel mining co. (1969) | |

| MP3: | bissett, “Air To The Bells/The Face In The Moon” (1967) from Past Eroticism (1986) | |

| Download: | bpNichol, ed. The Cosmic Chef: An Evening of Concrete (Ottawa: Oberon Press, 1970); derek beaulieu ed. (Visual Writing /ubu Editions, 2011) [PDF, 63MB] |

PennSound

When I first listened to the files (as the reader of this page is advised to do), I quickly recognized the singular contribution that Awake in th Red Desert might be heard to have made within the archive of countercultural poetics in the 1960s. I moved fast to get selections from the album up on PennSound, where they might be distributed to a very different community of listeners. As a first step, I wrote to bissett directly for permission. In an obligatory note on copyright, PennSound – unlike Mutant Sounds – operates as a strictly permission-based platform. Bissett responded with characteristic charm and inimitable style: “yes xcellent if yu want 2 put seleksyuns from awake in th red desert on pennsound that wud b awesum[.]” To augment selections from Awake in th Red Desert, I decided to “segment” a full-length reading bissett gave at the Bowery Poetry Club in 2006.16 Both recordings were hosted with embedded links to individual MP3 files. For some time, this was the extent of PennSound’s bill bissett collection. Recently, the page has accumulated a movie recording of the 2012 Book Thug launch of its republication of Rush: What Fuckan Theory as well as a radio program recording from around 1978 through the Robert Creeley collection.17 On another PennSound page, the user may also find a bissett track from the Carnivocal: Celebration of Sound Poetry album from 2004. From the Bowery Poetry Club back to See/Hear Records, the situation of Awake in the Red Desert on PennSound reveals a host of differences to the original upload.

| JPG: | bissett, from RUSH: what fuckan theory (1971/2012) | |

| MP3: | bill bissett & th mandan massacre, “my mouths on fire,” Awake in th Red Desert (1968) | |

| Download: | bissett Reading at the Bowery Club as part of the Segue Reading Series (New York: 2006) [ZIP: MP3, 31MB] |

While both Mutant Sounds and PennSound hosted precisely the same MP3 files – aside from the changed ID3 tags – the textual conditions of these two iterations could not be more different. As Charles Bernstein reminds us: “the fact is that the sound file exists not as a pure acoustic or sound event – an oral or performative event outside textuality – but as a textual condition, mediated by its visual marking, its bibliographic codes, and the tagging we give to it to mark what we consider of semantic significance.”18 An additional aspect to this condition, as theorized by Jerome McGann, is the social text. In other words, a more nebulous array of factors including reception, circulation, and context also inflect an object’s textual condition. To repost is to transform: not superficially, but at the most basic levels of a work’s significance. Here, we might note the immediate transformation from the lyrical “spew” accompanying “screw-loose outsider psych improv” in the music-based collection at Mutant Sounds to the institutional stamp of innovative poetry on PennSound. Where PennSound focuses on individual MP3s of poems and complete readings, Mutant Sounds releases only full album collections, previously published by a dispersed array of labels. Both sites push against canonical formations in their own way: Mutant Sounds against the tidy lineages of popular music, PennSound against the tidy lineages of mainstream poetry. There is a confluence of these genres in the work of bissett. Awake in th Red Desert works in both directions, and each site transforms the historical recording in its own way, for its own listeners. If, as Steve McCaffery has argued, bissett’s pioneering approach to sound poetry with Th Mandan Massacre was “significant in pushing poetic composition into the communal domain,” we might wonder in what domain it exists today.19

| JPG: | bissett, from Sunday work? (Vancouver: Blewointmentpress, 1969) | |

| MP3: | bissett, “5. And that light is in thee is in thee and,” SGWU (1969) | |

| Download: | bill bissett and bpNichol Interview with Phillis Webb (1968) [ZIP: MP4, 67MB] |

Despite the utter contrast of context, these two sound-based sites share a great deal in common. Like Mutant Sounds, the PennSound collection periodically releases audio recordings via a highly compressed MP3 audio format that typically remediates original cassettes, reel-to-reel tapes, vinyl records, and radio broadcasts. The collections both grow incrementally with each new digitized release, from a full series to an incidental recording. Primarily delivering files compressed to just 128 kilobytes per second, the MP3 actually prevents PennSound from official recognition as a poetry recording archive.20 Where other projects might acquire certain types of funding for digital archives hosting “lossless” formats like WAV or FLAC, PennSound’s emphasis on speedy distribution precludes it from archival classifications, despite the range and depth of its collection. Instead, like Mutant Sounds, the PennSound collection is built for user downloads. This approach reflects the uncertain future of the internet when the collection was founded by Charles Bernstein and Al Filreis in 2003. Even then, the MP3 offered a better alternative to the proprietary Real Audio format. Given its portability and accessibility, the MP3 remains the most popular format for audio distribution online. Popular arguments on the distraction inherent to the MP3 are weakened by the “close listening” techniques that poetry generically warrants. The recordings at PennSound earn this attention in sites as diverse as private academic research, university classrooms, and MOOC discussion boards. In remarks on the use of its thousands of poetry recordings, Filreis notes that the files have been downloaded by hundreds of millions of users. More perversely, we might imagine a million new versions across blog posts, syllabi, remixes, and other uses of the files.

| JPG: | bissett, from RUSH: what fuckan theory (1971/2012) |

|

| MP3: | bill bissett & th mandan massacre, “Arbutus garden apts 6 p m,” Awake in th Red Desert (1968) | |

| Download: | The Chemical Brothers, We Are the Night (New York: Astralwerks, 2007) [ZIP: MP3, 139MB] |

UbuWeb

Although Awake in th Red Desert is not hosted on UbuWeb, among the twelve hits for the string “bill bissett” on the site, there are two illuminating mentions of the album: both citations are from discographies. The first, compiled by Michael Gibb and originally included in the remarkable Sound Poetry: A Catalogue, is titled “Sound Poetry: A Historical Discography.”21 The second, compiled by Dan Lander and Micah Lexier for Sound By Artists is titled “A Discography of Recorded Work by Artists.”22 Of course, bissett is both poet and artist. However, the difference between the two – paired with the generic equivalence played out across the site – clearly bespeaks an entirely new condition for hearing bissett’s album. UbuWeb offers a less focused conjuncture, neither the musical archeology of Mutant Sounds, nor the poetry reading compendium of PennSound. Here the work joins with a wide range of objects beyond classification: outsider rants, conceptual art, structural film, concrete poetry, everything that might be read under the sign of the avant-garde, broadly construed. Other hits for “bissett” include articles by derek beaulieu and Steve McCaffery, a few concrete poems featured in various collections, bpNichol’s homage sound poem “Bill Bissett’s Lullaby” from Motherlove (1968), and bissett’s track “The Mountain Lake.” The last of these was recorded with guitar, tape, and “flux” as a contribution to an audio supplement to the 1984 sound poetry issue of The Capilano Review.23 Gathering this scattered assemblage of hits for bissett across the various sections of the site delivers a collection marked by the same intermedial disregard that characterizes the internet at large.

| JPG: | bissett, “o a b a,” Awake in th Red Desert (1968) | |

| MP3: | bill bissett & th mandan massacre, “o a b a,” Awake in th Red Desert (1968) | |

| Download: | The Capilano Review, no. 31, Sound Poetry (1984) [ZIP: MP3 14MB] |

However, the most interesting audio work by bissett on UbuWeb does not appear in any of the search results. Clicking through the extensive sound section of the site, a user might stumble upon the entry for Past Eroticism: Canadian Sound Poetry in the 1960s.24 The page hosting this digitized cassette simply breaks the audio into two MP3 files – Side A and Side B – in a technically convenient and tellingly remediated fashion. Aside from the title, there is no searchable text on the page. Instead, a JPG scan of the liner notes displays: “bill bissett (recorded 9/28/66* & 6/26/67**) / 7. Air To The Bells/The Face In The Moon** / 8. Valley Dancers* / 9. Colours*.” These three tracks immediately predate Awake in Th Red Desert, and anticipate that album’s generic freedom at the intersection of poetry, chant, song, and music. All three have been segmented for the first time for this page. Compared to the relatively metadata-scarce PennSound, the UbuWeb distribution of the MP3 file is even further stripped of context: “nude media” in Goldsmith’s terms.25 And yet, a truly interdisciplinary reading of the bissett files emerges through UbuWeb. If the files themselves carry little information, the context of their dispersion supports a robust network for an array of avant-garde productions in poetry, dance, sound, film, essays, radio, posters, and so on. All of which is compiled and released together with the happenstance bricolage of an assemblage magazine. Here, the bissett tracks merge with an undifferentiated conflux of historical and contemporary practices, regardless of the original social texts of the work. By betraying all contexts, UbuWeb creates a digital environment of utmost fidelity to the genre-blending work bissett set out to record.

| JPG: | bissett, from words in th fire (1972) |

|

| MP3: | bill bissett & th mandan massacre, “and th green wind,” Awake in th Red Desert (1968) | |

| Download: | bill bissett Tracks from the Past Eroticism Cassette (1986) [ZIP: MP3, 19MB] |

SpokenWeb

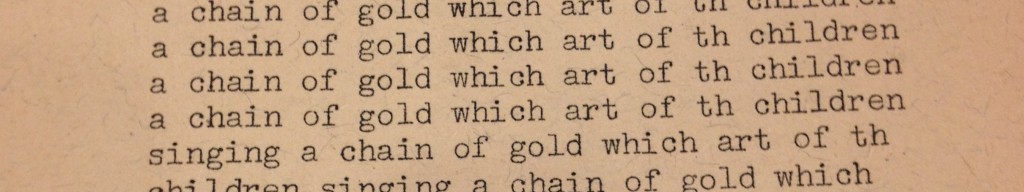

It is in relation to these three sites that I began to consider bissett’s performance in 1969 at Sir George Williams University (SGWU) as presented on the SpokenWeb digital poetry archive site. Recorded just one year after the release of Awake in th Red Desert, the SGWU reading draws from the same body of work that bissett deploys in his previous “recorded book.” As SpokenWeb tells us, with superb bibliographic attention, this reading by bissett features poems to be published in Nobody Owns th Earth (Toronto: House of Anasi Press, 1971); the lost angel mining co. (Vancouver: Blew Ointment Press, 1969); and OF TH LAND DIVINE SERVICE (Toronto: Weed/Flower Press, 1968). This last title is the organizing principle of the SGWU reading. It is also the only book released by bissett in the same year as Awake in th Red Desert. While the tape cuts off the opening, we can safely assume bissett begins with the first two poems OF TH LAND DIVINE SERVICE, given the pattern of works to follow: namely, poems “3,” “4,” and a variation of “5” in the cycle, followed by intermittent works from across the book and concluded with “moss song,” the final poem from OF TH LAND DIVINE SERVICE. However, the beginning and the end of the reading are both cut off. The failing of the archive here perfectly performs the play of in media res that bissett’s work demands. As Sterne reminds us: “sound recording is an extension of ephemerality, not its undoing.”26 Through no fault of the SpokenWeb editors, the lapse in the original mobile reel-to-reel tape recording renders the attentive metadata approach to this particular reading necessarily incomplete. There is no introduction to the reading, nor is there any commentary from the audience that we might analyze.27 The technical flaws in the reel-to-reel recording match perfectly with the aesthetics of assemblage, trans-genre performance, and intermedial nature of bissett’s poetics. In other words, to deform a track from Wershler, “bissett’s experiments on poetic excess yield highly specific social, historical and technological information about the shape and boundaries of what constitutes the permissible” in the contemporary audio archive.28 In this way, finally arriving at SpokenWeb, bissett delivers a fascinating case for practices that operate at the limits of the little database.

| JPG: | bissett, “Tarzan Collage” from Medicine My Mouths on Fire (1974) |

|

| MP3: | bissett, “Tarzan Collage,” SGWU (1969) | |

| Download: | bissett, Complete Segmented Reading at the SGWU Poetry Series (1969) [ZIP: MP3, 97MB] |

It’s useful to query these limits of the database with regard to SpokenWeb, if only because the collection is itself so attentive to its materials. Designed to investigate “the features that will be the most conducive to scholarly engagement with recorded poetry recitation and performance,” SpokenWeb offers “an interactive and nuanced tool that allows for deeper critical engagement with literary recordings.”29 Deeper, one might guess, than the formal qualities that structure the cultural practices applied to sprawling MP3 repositories like PennSound. This depth model is characterized by the site’s reflexivity, including sections that feature research perspectives, audio analysis and sound visualization resources, ongoing events and blog posts, oral literary histories, and commentary on other audio collections online. Further, all of these features are concentrated on a set of recordings from a single reading series held at SGWU between 1965 and 1974. Each reading is in turn broken down with introductions, bibliographies, transcripts, sources, and an array of metadata on the recording. Annie Murray and Jared Wiercinski have extensively charted the development of these features of the site: their papers on the subject are essential reading for the future of audio studies on the internet.30 This essay, on the other hand, is prepared to relate the output of a single recording within the SpokenWeb audio collection to a selection of related files hosted by Mutant Sounds, PennSound, and UbuWeb.

| JPG: | bissett, “4: a chain of gold which art of th children,” OF TH LAND DIVINE SERVICE (Toronto: Weed/Flower Press, 1968) |

|

| MP3: | bissett, “4: a chain of gold which art of th children,” SGWU (1969) | |

| Download: | Complete bill bissett IMG Set, Penn Library Special Collections (2013) [ZIP: JPG, 294MB] |

The differences between these sites and the SpokenWeb platform are, of course, quite pronounced. However, the commonalities they share may prove to be just as illuminating. Like Mutant Sounds, SpokenWeb sets out to map a network of relations in a given era of poetic production. Relating a community of practitioners in proximity to SGWU to an international group of poets and interlocutors, SpokenWeb presents the reading series as an “enormously intertextual affair.”31 The series is a sounding board for developing poetics and unlikely combinations. In this way, bissett is linked to his contemporaries at the height of his exploration of the technologies of publication and performance. Like PennSound, the collection is distinguished by its focus on the poetry series, a periodical collection not unlike the complete run of a little magazine. Rooted in a specific locality with a concrete set of recording devices and live contexts, hosting the poetry series online amplifies an approach to the slightest event of literary versioning. In Bernstein’s words, considering the sound file as part of the work “disrupt[s] even the most expansive conception of versions, all based on different print versions.”32 Both sites work to make this disruption possible. Like UbuWeb, SpokenWeb recodes its materials within an expanded set of concerns: bissett’s reading, like others featured on the site, is suddenly absorbed into an argument on digital platforms, the audio collection as an object of academic study, and the emerging problem of studying sound with digital analytics. Surely, this is the most unlikely context for these readings. Who might have imagined in 1969, when the recordings were made, that this inquiry would be the way in which these readings would come to be heard by a public audience?

| JPG: | bissett, from RUSH: what fuckan theory (1971/2012) | |

| MP3: | bissett, “bright yellow sky,” SGWU (1969) | |

| Download: | Selected Further Reading on Sound and bill bissett, PDF Collection (2014) [ZIP: PDF, 716MB] |

Listening to the poetry series at SpokenWeb today, it’s impossible to ignore the depth of the original series, with its unique constellation of readers and the wider poetics community at SGWU. But it is equally impossible to forget the context in which this collection surfaces. To listen deeply to a reading that bill bissett gave in 1969, the user must also hear a range of contemporaneous works hosted across the internet, to consider the digitization of the reading on a synchronic plane that includes versions circulating in unknown locations and unknowable configurations. For example, further afield we might add Strange Gray Day This (1965), a documentary film uploaded to YouTube in 2009, the sample from bissett’s “Pome for Oolijah,” used in The Chemical Brothers’ chart-topping record We Are the Night, or any number of further dispersed examples. A reading of any poet featured on SpokenWeb might, in this way, be differentially located on a map of the present. Rather than bind these threads into a single string, this page has aimed to select, edit, collect, and disperse. Beyond any single argument concerning the ways in which bissett might illuminate the audio-visual-textual confluence on these sites, this essay points to a variety of alternate readings that bissett might enable the user to consider. And this, I argue, is at the core of the digitized poetry reading. Already a kind of offshoot or supplement to the printed work, the social text of the historical reading radiates out to a wide range of materials from our present moment, on- and off-line. This argument seems to be at the core of SpokenWeb’s design. As a platform for scholarship, the site directs its user outward: to read historical publications, critical articles, technical details, and source materials into each recording; to read the culture of the online audio collection into the poetry series; to read the potential for a future use of digital tools into a little database of audio recordings; to read the digital file, the poem, the book, and the reading at once. This scholarship is built on the sheer potentiality of reading any narrative within the endless versioning processes of the internet. As such, like the audio recording itself, it remains in the realm of the virtual: the pleasure of knowledge is joined with the impossibility of full realization.

| JPG: | bissett, “wagon wheels,” Awake in th Red Desert (1968) | |

| Download: | Complete Amodern: LIVE VINYL MP3 Collection (2014) [ZIP: Various, 2.05GB] |

For example, before reading any further, the user may instead opt to download all materials presented on this page at the above link, which concludes the essay. ↩

Robert Scholes and Clifford Wulfman, Modernism in the Magazines: An Introduction (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 44. ↩

Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2002), 45-48. ↩

In particular, see Alexander Galloway, Protocol: How Control Exists After Decentralization (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2004); Jonathan Sterne, Mp3: The Meaning of a Format (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012); Lisa Gitelman, Always Already New: Media, History and the Data of Culture (Cambridge, Mass: MIT, 2008); and Alan Liu, Local Transcendence: Essays on Postmodern Historicism and the Database (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2008). ↩

See, for instance, Derek Beaulieu, Seen of the Crime (Montreal: Snare Books, 2011), 52: “Sadly in 2011 bissett’s books and performance upon repeated exposure become the work of an overwrought maraca-weilding hippie who’s overplayed LP is caught in a groove.” ↩

Darren Wershler, “Vertical Excess: what fuckan theory and bill bissett’s Concrete Poetics,” Capilano Review 2.23 (Fall 1997): 117. ↩

Mutant Sounds, http://mutant-sounds.blogspot.com ↩

See Bryan Gruley, David Fickling, and Cornelius Rahn, “Kim Dotcom, Pirate King,” http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2012-02-15/kim-dotcom-pirate-king ↩

For one example of these points, see Kenneth Goldsmith, “UbuWeb at 15 Years: An Overview,” http://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet/2011/04/ubuweb-at-15-years-an-overview/ ↩

Mark Allen, Brian Turner, Eric Lumbleau, et al. “The Rise and Fall of the Obscure Music Blog: A Roundtable,” http://www.theawl.com/2012/11/the-rise-and-fall-of-obscure-music-blogs-a-roundtable ↩

Apart from the description, this page is similarly defunct. Free Music Archive, http://freemusicarchive.org/curator/Mutant_Sounds/ ↩

“To collectors of unusual music the Nurse With Wound List is legendary. […] The NWW List covers the period from the late 1960s to 1980 when serious hybrids of avantgarde and popular music first became prevalent. It also covers a wide range of underground musical styles including krautrock, free jazz (improv), avantgarde classical, electronic, industrial, folk, aracho-punk, proto-punk, no wave, library music, and many more uncategorizable.” TGK, “The Nurse With Wound List,” http://nwwlist.org/ ↩

Alternatively, it should be noted that in the more radical variant, this activity has migrated to private torrent and file sharing communities like What.cd or the still-active Soulseek P2P platform. ↩

With apologies to Amodern editor Darren Wershler’s 10 Out Of 10, though I didn’t have to substitute for any of these words. See Mutant Sounds, “BILL BISSETT & TH MANDAN MASSACRE-AWAKE IN TH RED DESERT, LP, 1968, CANADA,” http://mutant-sounds.blogspot.com/2008/02/bill-bissett-th-mandan-massacre-awake.html ↩

Sterne, “The Mp3 As Cultural Artifact,” New Media & Society 8.5 (2006): 836. ↩

That is, create individual MP3 files for each poem recited in a full-length reading. For more on this process, and its importance to the collection, see PennSound, “PennSound Manifesto,” http://writing.upenn.edu/pennsound/manifesto.php ↩

See PennSound, “bill bissett,” http://writing.upenn.edu/pennsound/x/bissett.php ↩

Charles Bernstein, “Making Audio Visible: the Lessons of Visual Language for the Textualization of Sound,” Textual Practice. 23.6 (2009): 284. ↩

Steve McCaffery, “Sound Poetry: A Survey,” Sound Poetry: A Catalogue, ed. Steve McCaffery and bpNichol, (Underwich Editions, Toronto, 1978), 17. ↩

Even among internet pirates, this is a substandard data rate. See comment streams on Pirate Bay for complaints about anything released in less than 320kbps. ↩

Michael Gibb, “Sound Poetry: A Historical Discography,” http://www.ubu.com/papers/gibb.html ↩

Dan Lander and Micah Lexier, “A Discography of Recorded Work by Artists,” http://www.ubu.com/papers/artists_recordings.html ↩

For all of the above and more, search http://ubu.com for “bissett.” ↩

UbuWeb, “Past Eroticism – Canadian Sound Poetry in the 1960s – Vol. 1,” http://www.ubu.com/sound/eroticism.html ↩

“In thinking about the way that UbuWeb (and many other types of file sharing systems) distribute their warez, I’ve come up with a term: nude media. What I mean by this is that once, say, an MP3 file is downloaded from the context of a site such as UbuWeb, it’s free or naked, stripped bare of the normative external signifiers that tend to give as much meaning to an artwork as the contents of the artwork itself. Completely detached from shopping impulses, unadorned with neither branding nor scholarly liner notes, emanating from no authoritative source, the consumer of these objects is left with only the wine, not the bottles. Thrown into open peer-to-peer distribution systems, nude media files often lose even their historical significance and molt into free-floating sound works, travelling in circles that they would not normally reach if clad in their conventional clothing.” Goldsmith, “The Bride Stripped Bare: Getting Naked with Nude Media,” http://epc.buffalo.edu/authors/goldsmith/nude.html ↩

Sterne, “The Preservation Paradox in Digital Audio,” Sound Souvenirs: Audio Technologies, Memory and Cultural Practices, ed. Karin Bijsterveld and José van Dijck (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2009), 58. ↩

Jason Camlot has demonstrated the value of these paratextual components of the reading in his article on the SpokenWeb collection. See Camlot, “The Sound of Canadian Modernisms: The Sir George Williams University Poetry Series, 1966-1974,” Journal of Canadian Studies 46 (2012): 26-59. ↩

Wershler, “Vertical Excess,” 118. ↩

SpokenWeb, “About SpokenWeb,” http://spokenweb.concordia.ca/about/ ↩

See Annie Murray and Jared Wiercinski, “A Design Methodology for Web Based Sound Archives,” DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly 8 (2014); and Murray and Wiercinski, “Looking at archival sound: visual features of a spoken word archive’s web interface that enhance the listening experience,” First Monday 17(4), April 2012. ↩

For further resonance with the little magazine see Scholes and Wulfman, Modernism in the Magazines, 44-72. ↩

Bernstein, “Making Audio Visible,” 286. ↩