“Quantitative measurements will get you nowhere, and all descriptions are on their way to being out of date as soon as formulated.”1 So Rochdale College’s 1969 academic calendar prompted incoming residents as they prepared to join the then one-year old experimental free school at the north-end of the University of Toronto’s campus. For those weary of uppity collegiality and longing for community, Rochdale promised “a living articulate cross-section of contemporary society different only in being genuinely self- (often un-) determined, and in the openness with which its citizens act out both their joys and troubles.” Accordingly, “You may have trouble distinguishing between the academic, the therapeutic, and the vocational.”2

Between 1968 and 1975, Rochdale’s cast-in place concrete tower housed thousands of residents. At eighteen stories Rochdale was North America’s largest free school and a vital hub of countercultural activity for both Canadians and newly arrived American ex-pats. An unprecedented operation, the College arose from a conjunction between a modest experiment in non-hierarchal participatory learning, an ambitious student co-operative project, and the Liberal federal government’s renewed attention to education and youth employment as the economy began to shift away from industrial production.3 Over a period of seven years, the College and its community cycled through moments of high ebullience and trouble—hosting countless cultural and social organizations, negotiating the circulation and sale of drugs, entrusting security to an ad-hoc team of bikers, managing a crippling mortgage, and enduring constant struggles to maintain democratic self-governance. Internal pressures that, combined with public persecution by the police and the media, ultimately contributed to Rochdale’s closure.4

Rochdale, of course, was part of a broad movement in alternative education, its scale, ambition, and notoriety locating it within an international matrix of radical flashpoints. Yet, as poet, teacher and one of Rochdale’s principle founders, Dennis Lee recalls the experiment was motivated by a pronounced desire for autonomy beyond typical alternatives:

[I]t could have taken the direction of the standard model of the time for a ‘free university,’ which simply meant a few score people who would get together and create courses that they couldn’t study at the local university. But the hope was that it would not be just a counter-institution, but that it would have its own dynamics and its own reason for being.5

The term ‘counter-institution’ is one that requires some unpacking. To Lee, it described something positive, yet all too common at the time. Although coordinated as alternatives such projects ultimately remain tethered to and determined by that which they were positioned against. And while existing processes and environments might be rejigged, for Lee they lingered around this adversarial position for too long instead of making the leap into new motives. No matter Lee’s categories, Rochdale was for many residents and observers a vital counter-institution. In her study of the expatriate scene in Canada, René G. Kasinsky uses the term in reference to Rochdale and a range of other organizations and services accommodating the war resister community.6 Following a visit by Vancouver artist Gary Lee-Nova and poet Gerry Gilbert in 1969, together representing the prototypical artist-run centre Intermedia, a newsletter printed at Rochdale reported that the guests were excited by what they saw in Toronto and hoped for future exchange between the two “counter-institutions.”7 A 1972 guidebook to Toronto’s alternative organizations published by artist-run centre A Space further positioned the College as part of an ecology of new and recalibrated institutions.8 Indeed, with a portion of its rentals going to small, independent organizations Rochdale itself could be though of as an aggregate of counter-institutions.9

Considering Rochdale’s promise to confuse the embodied and perceived boundaries between the sensorial and socio-economic conditions of education, it’s necessary to situate the experiment in ratio with coeval projects underway in Toronto. These included The New School of Art, the Ontario College of Art, and Harley Parker’s exhibition designs at the Royal Ontario Museum. It is with Parker’s work in mind that I follow up with a detailed profile of one of Rochdale’s earliest amenities, The Same 24-hour restaurant. Designed by artist, publisher, ex-architecture student, and Rochdale resident Ken Coupland the restaurant is an unlikely yet suitable foil to Parker’s exhibition designs (both realized and projected). Where Parker is concern with the contemporary relevance of the museum experience when confronted with the “participatory wakefulness” of its audience as compelled by electronic media, I propose that the design of Rochdale’s restaurant equally aimed to better calibrate its built environment to its immediate context. Moreover, I suggest that in its own way this design agitated the College’s past and present filiations as a means of foregrounding a possible future against the dual obligation to status-quo counterculture and administrative prescriptions.

The New School of Art

Students attending The New School of Art were among Rochdale’s first residents. Founded by defected faculty from the Ontario College of Art, The New School offered a studio-based curriculum that privileged students as artists. Writing in arts/canada, artist and pedagogue Vera Frenkel described the general atrophy of art education in Canada as a condition of “teachers teaching teachers to produce teachers” resulting in little more than “a hall of mirrors for the passing on of second-hand experience.”10 The New School brought its body of “neophyte-artists” into contact with a faculty of legitimate (read: exhibiting) artists, in addition to guest instructors from outside fields including computer design and psychiatry. To Frenkel’s eyes it was “a human environment laboratory” coordinating “insight-explosions” previously unavailable under the watch of the Ontario College of Art’s conservative administration.11.

Such results were not exclusive to The New School and Frenkel notes similar promise in the soon-to-open Rochdale as well as experimental grade schools Everdale and Superschool.12 Further evidence of a turn toward student-centered and experiential learning is found in a newly drafted provincial report on education. Officially known as The Hall-Dennis Report and subtitled Living and Learning the document offered some 260 recommended changes to the primary and secondary education system in Ontario.13 These included projections for individualized learning, the abandonment of certification, and a sweeping de-hierarchization of the school system. The report outlined a program that foresaw a passage of study that allotted students with more freedom and choice in the direction of their studies as they progressed toward graduation.14 Field research, such as a survey of existing school architecture, was complimented by feedback from a wide range of advisors, among them Marshall McLuhan, and incorporated ideas from progressive educator A.S. Neill, philosophers John Dewey and A.N. Whitehead, and psychotherapist Erik Erikson.

Ontario College of Art

In 1971 Ontario College of Art appointed British artist and pedagogue Roy Ascott as president. Ascott was entrusted with lifting the school out of a stodgy curriculum mired in traditional training that had exasperated relations with the student body and faculty for too long. Rechristening the College as a “visual university” Ascott built his curriculum around an open foundational course guided by concepts drawn from cybernetics and communications theory, ideas key to his own practice.15 With a nod to Buckminster Fuller’s strategic questions, Ascott foresaw that students entering second year would spend a month investigating the question: “What is man?”16 Following this they were expected to anchor their curriculum in a “cultural probe” combining “a search and questioning in: life sciences, social studies, analysis of art systems, future studies.” This inquiry would then animate the three key elements of learning: structure, information, and concept, each further subdivided into the areas of analysis, theory, speculation, and social application. His tenure at the newly minted “visual university” was brief. For some the new curriculum was a radical break and much needed release for the College long seen to be behind the times. For others it only exasperated anxieties and divisions, as one newspaper headline reported with a nod to futurist Alvin Toffler, “Students and faculty are confused as ‘future shock’ hits our art college.”17 Ascott’s tenure was short, making as many friends as enemies his privileging of contemporary materials and processes further antagonized relations with faculty working in more traditional media. After some questions arose concerning his professional qualifications he was suspended and dismissed from his position in the spring of 1972.

In British Columbia similar experiments had already come and gone. Opening in 1965, The Centre for Communications and the Arts at Simon Fraser University was modeled as a “sensorium” for learning. Coordinated by composer R. Murray Schafer, the curriculum eschewed the dominance of the visual in art education. Instead, learning would claim no allegiance to one discipline in order to focus on the full sensorial experience of the students, a model described by Schafer as “synaesthetic.” Iain Baxter experimented with “non-verbal teaching,” delivering lessons through a series of silent yet “highly rhetorical” gestures. Students examining the question of “scent” consulted a cosmetician and a pestologist, while on another occasion, a physiologist was invited to present on the science of vision.18 The experimental nature of the program, however, was not embraced by the university’s administration and in 1969, following a three-year trial period, the Centre was dissolved leaving students to choose from discipline-specific faculties.19

Harley Parker’s Royal Ontario Museum

Because they do have some autonomy outside the educational system museums could be the first to use electronic communication techniques properly; not with the flat-footed pedestrianism of most educators nor with the misdirected enthusiasm of the hippies, but with invention coupled to an imaginative insight into the mores and real educational needs of our age.20

Thinking through his 1967 redesign of The Hall of Fossil Invertebrates at the Royal Ontario Museum, Parker appears dismissive of any wholesale presumption that new techniques of electronic communication might simply serve as an adjunct to traditional education. Any uptake within hippie culture is thought to be equally unconvincing. For Parker, the museum’s potential rested with its capacity to break from its nineteenth century origins and become a forum attuned to the “present sense.”21

Of course, McLuhan is the common, if reluctantly accepted, bond between Parker’s thought and contemporary experiments in education accommodating a growing hippie constituency. An intimate of McLuhan’s, Parker’s thoughts on museum designs share in a complicated and thorough navigation of the bind between communication, space, and sensorial data as figured within new models of education. Similar pronouncements can be found circulating through the examples surveyed above. Frenkel’s “insight explosions” match the “flash insights” Parker describes in an earlier article.22 In this same text, Parker notes: “we must be prepared to accept the idea that a re-appraisal of cultural articulation can “cleanse the doors of perceptions” and act as a constructive element in the reorientation of the human mind.”23 Thinking about the program at Simon Fraser University, Schaefer simply transposes “doors” for “lenses.”

Though Parker saw great potential in the museum and its manageable distance from the educational system, it is doubtful that he would have nominated it counter-institutional status or membership. Rather, he envisioned a “newseum” physically operating alongside the traditional museum. Coordinating its exhibitions around topical events in knowledge and politics Parker’s newseum would draw on the neighboring museum’s collection as a means to invite the public to think through contemporary issues by way of sensorial immersion.24

At Rochdale qualitative, empirical dispositions were thought incommensurable against its disciplinary formlessness, such an encounter further demonstrating how out of pace academic systems really were in the face of the electronic speed-up of contemporary thought. Museums, according to Parker, were encumbered by linear thought and an obstinate “visual bias” that maintained that all that was required to contemplate a set of information was a suitable vessel. Surmising that education is ultimately a question of structure, Parker approached data not as an isolated object but as something actively constituted through associative thought and experience. In other words, the guiding armature of education is to be constructed and determined by the mutable ratios between the objects of study. Here we find correlation with Lee’s wishes for an institution determined by “its own dynamics.”

One corollary of Parker’s redesign of The Hall of Fossil Invertebrates was that it agitated the ratios between the Museum’s other displays. A visitor experiencing the Hall’s rear-projections, semi-abstract dioramas, ambient audio, piped in odors, and optical patterns would surely be compelled to make a comparison with the other, more traditional exhibitions. Indeed, for Parker the urgency was palatable—“Maybe, just maybe, this hall is a first step toward the placing of museums in the twentieth century which is, incidentally, rapidly drawing to a close.”25

It is from here that the leap can be made between Parker’s displays as embedded within the museum and the dynamic between Rochdale and its restaurant. Where Parker’s hall betrayed the museum as a tired anachronism, disturbing its aggregate form as a set of containers for information and making the case for it as a mechanism constituted out of information, so Coupland’s designs, articulated in space and on the printed page, troubled the historical tense, built boundaries and tenuous radicalism of Rochdale’s experiment.

The Same Twenty-Four Hour Restaurant

Designed in a Brutalist style by architects Elmar Tampõld and John Wells Rochdale’s grey high-rise was but one example of a series of buildings that had started to appear along Bloor Street, bringing the strip, as a study of Toronto’s concrete architecture notes, into the “space age.”26 Yet, for some residents the austere environ remained too closely aligned with the institutional spaces they were rejecting, while for others it provided a literal fortress and refuge wherein a new community might unfold unimpeded.27

Prior to the construction of the building a group of students, teachers and participants frustrated with the conservatism of conventional university education came together to conduct seminars founded on the principles of non-hierarchical learning.28 Coordinated by Dennis Lee and John MacKenzie, the Rochdale Houses included six buildings on and around the University of Toronto’s campus accommodating a membership of roughly 160, half of whom were residents. Learning was shared, discursive, and improvised. It was initially imagined that the layout of these domestic spaces would be transferred over into the new high-rise building. The final outcome, however, was cold and utilitarian as the project’s secondary mortgage holders, Revenue Properties, enforced at the last minute strict conditions requiring the floor plans to be based on the configuration of the underground parking lot.29

Nonetheless, the basic format of the early workshops was extended to the larger Rochdale project where “resource people” replaced teachers. These were academics, adherents, entrepreneurs, and artists solicited to propose and lead workshops. In exchange the College offered to these individuals reduced or free accommodation. The scale of the Rochdale experiment, both its building and the population within, was unprecedented and the loose curriculum soon propagated via an improvised and constantly changing network of resources and services taking advantage of the cheap rent and built-in constituency.

A plethora of printed matter further extended the possibilities of Rochdale’s built environment. Important amongst this material was the Daily newsletter, printed and dispatched weekly by neighboring Coach House Press.30 The single sheet bulletin brought together council minutes, classified ads, personal notes, lifestyle suggestions, seminar and workshop descriptions, and advertisements, along with an assortment of graphic oddities. The bulletins were distributed throughout the building by a team of volunteers who would slip copies under each apartment door. With its frequency of production, its range of content, and wide dissemination, the Daily served as a vital, if at times vulgar, “connective tissue”—the phrase comes from artist AA Bronson— and a printed annex to the College’s assigned architecture.31 Indeed, this idea of Rochdale’s printed matter as a spatial adjunct can be read in another internally produced publication:

IMAGE NATION means where you locate—whether it be inside your body, your mind, on the street, in school or even Port Alberni or Roberts Creek, BC —looking around at what you know. Rochdale is a unique opportunity for communal design. IMAGE NATION is a working ground for such an effort.32

It is by way of this idea of communal design—the shared design of a new community and the printed plane as its support and forum—that the first pronounced architectural intervention at the College, The Same 24-hour Restaurant, can be approached.

Opening in the fall of 1968 and operating for just over a year The Same was a pronounced futuristic and sensorial apparatus. Accessed at street level, it served as a liminal site between the new society developing within Rochdale and the larger world outside. Plans for a restaurant were underway before Rochdale officially opened to the public. Residence included room and board, food services included a cafeteria on the second floor and communal kitchens on floors laid out following an “ashram” model (a compromise in the building’s architecture secured through much negotiation). Just below the cafeteria at street level there remained an unoccupied commercial space lined with large windows. Reserved for a restaurant servicing both residents and the public, it was the governing council’s hope that such an operation would provide a steady stream of income to the College.

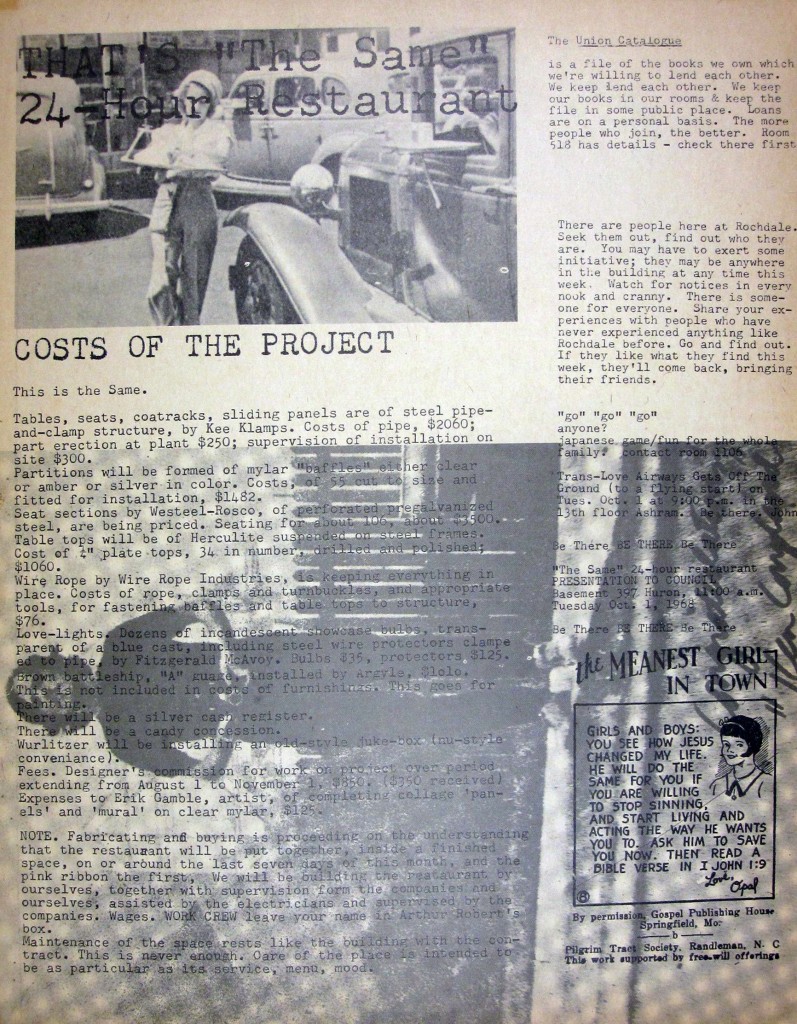

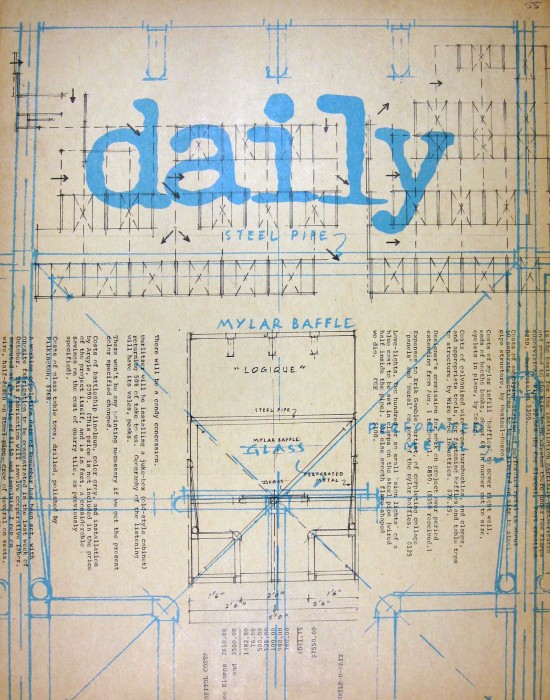

During the summer and fall of 1968, Coupland was responsible for many of the layouts for the Daily. In these months leading up to the College’s opening, where the chatter of residents had yet to commence, he used the newsletter to distribute architectural drafts and information on the restaurant. One undated Daily enumerates the material and labour costs of his design.33 Printed over a snapshot of himself, the list read more like an inventory for heavy industry than the make-up of a restaurant ready to service Toronto’s new countercultural Mecca: steel piping and clamps; slabs of Herculite reinforced vinyl; sheets of coloured metallized Mylar; panels of perforated pre-galvanized steel; spools of wire rope, and dozens of incandescent showcase bulbs. Only the inclusion of a silver cash register and a fifties-style jukebox betrayed the purpose of all this material. Indeed despite its futuristic look Coupland’s design was ultimately based on a classic diner layout.34 The restaurant was expected to accommodate 106 diners and would be open around the clock. At the moment of publication, construction was projected to occur during the last week of September and the governing council was scheduled to visit the new restaurant on September 30th, in order to christen the eatery and mark the commencement of the College’s official opening week.35

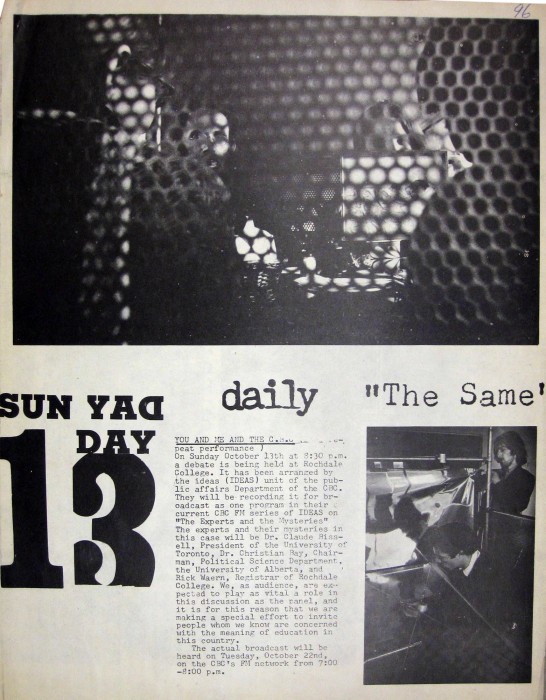

Image 2: Daily, October 13, 1968, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 9.

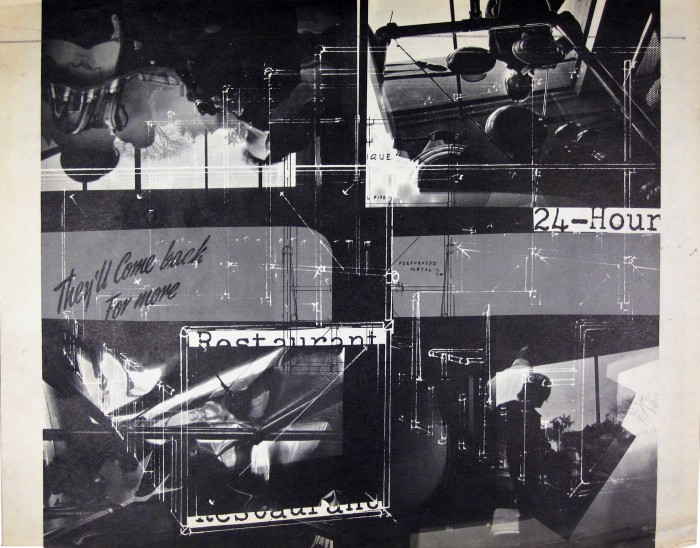

Image 3: Daily, October 13, 1968, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 9.

Despite some minor delays, Coupland’s novel use of industrial material proved to be successful and the structure was easily mounted in the early weeks of October. The October 13th edition of the Daily served as a photographic portfolio of the newly opened eatery. The front side featured a large black and white photograph of a group of four diners observed through the perforated steel seating of a neighbouring booth. A smaller photo on the same page shows the space in its final stages of construction, with Coupland himself adjusting one of the coloured baffles. To the top right of the backside is an ant’s eye view looking up through a transparent tabletop, upon which the dishware appears to float freely. To the bottom left a close-up photograph of a baffle, demonstrating its optical and material qualities in contradistinction to the ridged steel tube armature. The remaining photos featured silhouettes of diners in their booths with the large sheet windows looking onto the street. A view looking inside through those same windows was later incorporated in two versions of the 1969 course calendar, available in a booklet and folded formats, both showcasing a packed service at the restaurant.

Throughout the month of October small graphic advertisements for the restaurant continued to appear in the Daily. Making use of Coach House’s bank of graphics and typefaces, they paired simple illustrations of modernist and art deco skyscrapers with groan-worthy phrases set in brush stroke styled fonts, reminding the reader that “They’ll come back for more of: The Same.” These advertisements crept into the layouts, adding to the weekly textual cacophony that continued to rise as more residents arrived. The choice of fonts and imagery recalled enthused print advertisements of the post-war boom, and further accentuated the popular restaurant architecture upon which Coupland based his designs. For example, an advertisement for the restaurant on the back cover of Image Nation featured a photograph of a formal ball, the couples dancing at arms length beneath the phrase “Welcome to the Club.” This contrast between the advertisement’s vintage graphics with the restaurant’s futuristic design gave further force to the play in tenses at root in Coupland’s project.36

Early on the restaurant was heavily used, and abused, by the internal population—one announcement in the Daily pleaded with residents to return three hundred missing forks.37 And after just months of operation the restaurant had become a topic of concern for the governing council. A key issue at the November 27th meeting the council was depending on The Same to be a stable and lucrative enterprise in order to keep mortgage payments at bay.38 The delayed construction due to the late delivery of building materials was in part to blame for a shortfall in revenue.39 To save on costs it was decided that the restaurant would be closed over the winter holidays.40

Come the New Year and the return of much of Rochdale’s internal population The Same remained closed.41 Mention of the restaurant in print only reappeared near the end of the winter. The March 1st edition of the Rochdale Supplement, occasionally included with the Daily, featured an interview conducted in the restaurant by science fiction writer and Rochdale resource person Judith Merril with the band The Mothers of Invention (sans Frank Zappa).42 The spring season also welcomed the college’s culinary resource person Wu as the full time manager of the restaurant.43 Under Wu’s charge the menu expanded into a new modular form of gastronomy. A feature on the College published in Maclean’s enumerated but a small selection the myriad of choices now available:

19 kinds of honey, including linden, rosemary, and mellona; caviar at 40 cents a portion; 25 kinds of coffee, from straight Canadian to dandelion; 23 kinds of tea, from tea-bag through something called Constant Comment to Yerba Mate; 10 varieties of smoked meats; 22 variations on the theme of jam; and 23 flavours for milk shakes, including anise, bilberry and tamarind (a rare Indian date).44

This new, seemingly interminable, menu was well suited to Coupland’s design. Wu was quoted in the Maclean’s article as finding his work at The Same as “less inhibiting” than his other role of preparing daily meals for residents in the cafeteria. Just as the industrial and standardized make-up of the restaurant’s booths suggested a flexible dining space so Wu’s menu carried the potential for constant culinary permutations as diners assembled their meals ingredient by ingredient. Artist and early resident AA Bronson recalls how this combination of an expanded menu, ceaseless jukebox, and dynamic architecture emerged within a molasses thick passage of time, part drug induced, during the long waits for orders to arrive as Wu invented a new dish for each diner.45

With Wu now in charge of the kitchen it appears that by spring, close to half a year after opening, The Same had finally hit its stride. The restaurant continued to run smoothly up to the summer months when it once again became a subject of the council’s concern. In June the community at Rochdale was gearing up for the Toronto Pop Festival and it was expected that the transient population in the building would increase significantly over the festival’s run. A motion was passed to close the restaurant until the excitement around the festival had subsided.46 The festival came and went; the restaurant remained shuttered for the rest of the summer. Over these months professional caterers were hired to help Rochdale cope with the hundred thousand dollar debt it had amassed in just one year of operation.

Come the first week of September The Same reopened with significant changes to its operations and menu.47 No longer open for twenty-four hours and it now served mainly hot dogs, hamburgers, and chips; a menu no different than the cafeteria located above it or any fare available elsewhere in the vicinity.48 Later that month resident Jack Jones voiced this inquiry in the Daily: “The restaurant seems clean and nice, but not very Rochdale. I wonder if we can do something about that? Food? Decor?”49

Jones’s inquiry was published September 30th; a year to the day after the restaurant’s presentation to the council was reported. Sure enough The Same was closed yet again for renovations. Along with a new cooperative work program, steam tables arrived to replace Wu’s spur-of-the-moment concoctions. The cancellation of the around the clock service was also part of the council’s attempts at policing the growing presence of amphetamine users and non-residents, thought to use the restaurant as an easy passage into the building. Soon enough the rest of Coupland’s industrial material was packed up and replaced by the wood paneling and rustic décor of Etherea Natural Foods. Run by the Etherea commune, the new restaurant and health food store paid the rent on time, providing the college with a source of revenue that The Same was unable to generate.50 The legitimacy of hip capitalism was a potent topic around the college. In an editorial for the Canadian Whole Earth Almanac, for which Coupland was managing editor and designer, Tracy McCallum figures that money followed the growing popularity of alternative lifestyles. The question then is how this capital is used:

In the case of the hip merchant, if the end is to be able to buy a new mustang and a swimming pool, then he’s not hip. If the end is to be able to move to the country, finance the building of one’s own home and grow an organic garden, i.e., do more with less, then he’s not a capitalist.51

Clearly, in its bid to lend the college further fiscal autonomy, The Same fell into the latter category. Yet, the resistance to Coupland’s design also betrayed the conservative measure behind the outward forms that “hip (non) capitalism” could take. As Parker with his sensorial exhibition design down the street at the ROM aimed to expose the limits of the museum’s antiquated glass cabinets and categorical display, so Coupland’s futuristic restaurant provoked the restoration of a rather normative hippie aesthetic and business operation. Each part of a larger, para-academic institution, Parker’s hall and Coupland’s restaurant in their respective ways struggled to address Toronto’s hippie population with Parker’s suspicions of the restraints of hippie idealism confirmed in part by the reaction to Coupland’s restaurant.

While some residents perceived an irreconcilable contraction between their lifestyle and the College’s assigned architecture Coupland surely recognized that the material capacity of concrete was not stagnation but permutation. Having studied architecture at University of Toronto and thoroughly immersed in the local counterculture Coupland was well aware of the fantastic urban propositions emerging from the megastructure movement, famously chronicled by Rayner Banham in his 1976 study Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past.52 Propositions such as UK-based Archigram’s Plug-In City, Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome and the larger complex of Expo 67, ex-Situationist Constant Nieuwenhuys’s New Babylon, and Cedric Price’s Fun Palace all envisaged new forms of architecture in which shelter, entertainment, commerce, and leisure could be housed within one comprehensive built environment.53 Utopian in nature these propositions looked towards the full integration of technology to realize adaptive spatial networks, buildings and cities as open systems in synch with McLuhan’s “electronic speed-up.” These designs promised a cross wiring of architecture with individual and collective desires, adaptive environments responsive to each of inhabitant’s impulses. Moreover, Coupland’s friend, AA Bronson, who had previously studied and dropped out of the architecture program at the University of Manitoba, had in 1967 co-produced Junkigram! a sensational and critical one-off newspaper on radical architecture.54

Indeed, University of Toronto’s suburban outpost, Scarborough College, designed by John Andrews and completed in 1965, is among Banham’s examples of academic megastructures. Noting the persistence of megastructures within Canada, Banham suggests that the massive concrete campus in Scarborough and others like it were in part the result of a “Canadian accountancy megatrend”—namely, the cold weather.55 Key among his examples are A.J Diamond and Barton Myers’ University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta which featured a 800-foot covered street combining student residences with shops and York University’s indoor piazzas.

Rochdale’s concrete housing brought it in sync with both existing and planned structures across Canada. Yet, Banham writes, while “the concept of the university as a mini-city or a sample city neighbourhood was remarkably persistent,” with or without meteorological necessity, “[s]ocially, and in many other ways, the university campus was too impoverished an example to serve as a useful test-model for real city situations.”56This impoverishment was precisely what directed marooned students to Rochdale. In a sly gesture toward the growing commodification of university certification, the college’s governing council masterminded a fundraising campaign that offered customized, phony degrees for sale by mail.57

Plugged in at its base, The Same confirmed the college’s ambitions to provide the necessary framework for a total living and learning environment. However, unlike the University of Alberta’s arcade-like refuge from the harsh prairie winters, Rochdale was another sort of asylum. Regular police crackdowns in neighboring Yaletown combined with growing gentrification saw the quarter’s population surge into the building, the horizontal world of late-night coffee houses and hippie patrons redistributed vertically throughout the tower.58

While the futurological propositions of megastructural design might have served as arcane delights to architecture students, enrolled or dissenting, by the fall of 1968 the majority of Canadians were already familiar with the standard look of utopian architecture. Montreal’s immensely popular Expo 67 with its network of pavilions and man-made islands served as a training ground for what architecture historian Inderbir Singh Riar refers to as a new “citizen-participant.” For many Expo 67 visitors architecture took on a surprising new character. The experience of free ambulation throughout and between pavilions, in combination with a ceaseless barrage of sensorial data, foregrounded the spectator’s own role in the overall event and introduced a notion of learning (bound up with a muddling of corporate and national identity) as a multisensory activity.59

A year later in Toronto passersby on Bloor Street could peer into the street-level restaurant at the foot of North America’s most ambitious countercultural community. Inside they would see diners and staff corralled within a steel-tubular structure, a system of booths slipped into the foot of a towering concrete box, and looking as if it had been constructed from cast off material from Expo 67’s futuristic city. Around the clock the restaurant advertised and affirmed Rochdale as a utopian-minded project, a rag-tag parallel to the highly stylized meeting of nations and industry in Montreal.

Many megastructure projects existed solely as propositions spread over essays, publications, models, and illustrations. Architectural theorist Anthony Vidler has suggested that this pairing of architectural conventions and futuristic projections gives rise to an uncertainty as to if such projects will unfold toward utopian or totalitarian ends. Referring to this as the “representation effect,” Vidler notes that the critical edge of megastructures lies in this ambiguity, leaving the viewer to wonder if the inhabitants are liberated by a sensorial and adaptive architecture or apprehended and exploited by its acute surveillance of life at interpersonal and affective strata.60

For Coupland the newsletters provided a forum wherein he could anticipate the sensorial experiences of his design. Moreover, this speculative drafting provided a means to figure the restaurant beyond its budgetary and material constraints. Instead of seamlessly bridging the divide between the virtual space of the printed page and the real space of the College, these documents called attention to the reader’s dual occupation of these realms.

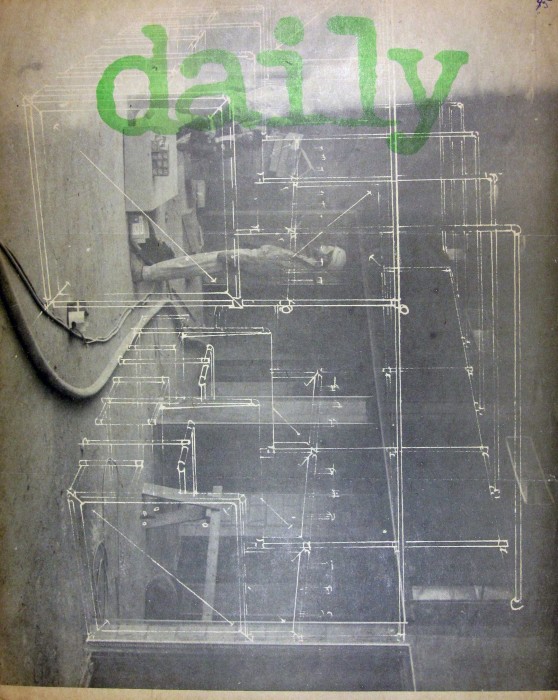

Image 4: Daily, September, 1968, , Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 9.

On the reverse side of the Daily from the early fall of 1968 is a precise montage transferring a drafted plan onto a photograph of the actual space it would come to occupy. Rendered in white, the overlaid design suggests the cool luminescence of the proposed metal and plastic armature. Readers could then consider the restaurant as they might approach it upon entry. The underlying photograph also revealing Rochdale’s delayed state of construction—electrical cables snake across the floor, exposed cinderblocks betray unfinished walls and columns, various tools and materials are strewn about, all covered with a chalky dust. Amidst the debris are two figures, one standing in the centre of the room, presumably facing the street, and another seated further back on some low-lying debris. At first glance this photograph could be assumed to be a convenient study of the space, the perspective and relative bareness of the setting suited to Coupland’s needs. However, the location and position of the two figures neatly corresponds with the overlaid design and suggests a careful staging: the standing figure situated in an aisle, perhaps as a server attending to the second seated figure now seen within a booth.

Image 5: Daily, September, 1968, , Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 9.

In another edition of the Daily it is the reader who is placed within the coming design. Under a light blue title is a tangle of three booth plans and textual information. The page is framed by a draft of a booth viewed from the side with the back of each bench marking the limits to the left and right edges. Steel tubing extends vertically up to the top edge of the page where it would be expected to connect the booth to the larger tubular system. Here Coupland’s layout proposed the infinite continuation of his design from a single fixed point, as if the page of this Daily shared the view of the seated figure in the construction site, peering out of one booth and into another. The textual data also provides details missing from the layout. Included is additional information on building materials, a working schedule, as well as an enumeration of atmospheric experiences—“There will be a candy concession,” “Wurlitzer will be installing a juke-box…geography of the listening will have its vales, peaks,” “Love-lights.” Labour costs are also accounted for, including Coupland’s fee and another to artist Erik Gamble for some collage work to be applied to a selection of baffles. The total amounted to $7550, its inclusion demonstrative of the College’s attempts of sustaining an open society rooted in fiscal and informational communality.

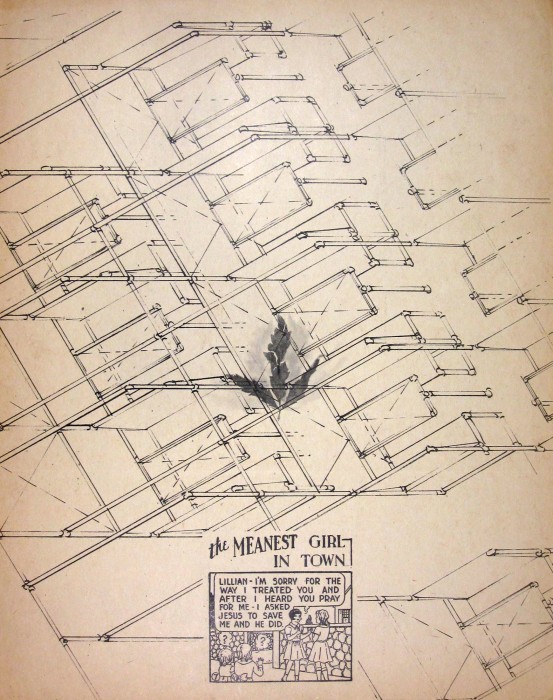

Offering further elaboration of Coupland’s plans, the reverse side of this same newsletter is dominated by a bird’s-eye view of the restaurant’s booths. As if viewing the restaurant from the College’s highest floors the plan sketches in hard black lines a complex arrangement of tubes, wire, and plastic.

Image 6: Daily, September, 1968, , Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 9.

Apparent are the structural connections between booths as tubes snake through metal clamps to trace out one booth form after another. In the centre of this dense lattice a print of a small branch, a token of the recognizably organic lest there be worry of its exclusion. To the bottom of a page is a panel extracted from the “The Meanest Girl in Town,” a morally assertive Christian comic that had been appropriated and embroiled in Coach House and Rochdale’s weekly graphic and textual tumult.61 Here Coupland’s plan expands beyond the dimensions of the page as if to prove its easy execution, modular nature, and potential for growth. Indeed, taking the whole run of this edition and lining it up edge-to-edge would simulate such a mutation.

With his design Coupland refused direct confrontation with the building’s seemingly impenetrable austerity. Rather he insisted on a collaborative relation, resulting in a foregrounding of the latent mutability of concrete. This understanding of the material’s plasticity, the possibilities derived from immediate on-site casting, was imbued in Coupland’s restaurant design. The addition of the steel and plastic eatery literally recast Rochdale’s concrete real estate as but one interval within a larger utopian project. His ironic design flirted with the functionalist and egalitarian objectives of the tower’s diminished Brutalist style while simultaneously setting itself in contrast to the persistent hippy status quo preferring the handmade, organic material and earthy colours. With chromed jukebox in the corner The Same dressed the College in futuristic drag, repositioning and stimulating its hippie customers as anachronistic visitors in the present sense, be they time-travellers from a coming hippiedom or present-day freaks wandering into a future amenity.

Rochdale is… (Toronto: Coach House Press, 1969) n.p. ↩

Rochdale is… n.p. ↩

For more on the correspondence between Rochdale’s rhetoric and the federal government’s see my text “Let The Buyer Beware,” A Play to be Played Indoors or Out: This book is a Classroom, eds. Corinn Gerber, Lucie Kolb, Romy Rüegger. (Zurich: Passenger Books, 2012). ↩

For more on Rochdale see Howard Adelman, The Beds of Academe: A Study of the Relation of Student Residences and the University (Toronto: Praxis Press, 1969); Brian J. Grieveson, Rochdale: Myth and Reality (Haliburton, ON: Charasee Press, 1991); Stuart Henderson, “Off the Streets and into the Fortress: Experiments in Hip Separatism at Toronto’s Rochdale College, 1968–1975,” The Canadian Historical Review 92.1 (2011): 107-33; Sunny Kerr, “Rochdale College: Failure Studies in Toronto” in Wood, ed. Christof Migone (Mississauga, ON: Blackwood Gallery, 2011) 114-17; Dennis Lee, “Getting To Rochdale,” This Book Is about Schools, ed. Satu Repo (New York: Pantheon, 1970) 354-80 Henry Mietkiewicz and Bob Mackowycz, Dream Tower: The Life and Legacy of Rochdale College (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1988); Ralph Osborne, From Someplace Else: A Memoir (Toronto: ECW Press, 2003); David Sharpe, Rochdale: The Runaway College (Toronto: House of Anansi, 1987); Robin Simpson, What We Got Away With: Rochdale College and Canadian Art in the Sixties, MA thesis, Concordia University, 2011; Peter Turner, ed. There Can Be No Light Without Shadow (Toronto: Rochdale Press, 1971); Dream Tower, dir. Ron Mann, Sphinx Productions, 1994. ↩

Qtd. in Mietkiewicz and Mackowycz, Dream Tower, 18. ↩

René G. Kasinsky, Refuges from Militarism: Draft-Age Americans in Canada (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Books, 1976): 189-190. ↩

Daily, 28 February 1969. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 9. ↩

Isobel Harry and Marlene Sober, eds, Vehicle: Handbook of Toronto Cultural Resources (Toronto: A Space, 1972). ↩

Indeed, this activity was also compounded within Rochdale, a partial list of some of the organizations working out of and in collaboration with the College includes: Theatre Passe Muraille, Canadian Whole Earth Almanac, Coach House Press, the Spaced-Out Science Fiction Library, the Institute for Indian Studies, Alternative Press Centre, Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre, Hassle Free Clinic, and the Women’s Involvement Program and Liberation Media. This in addition to countless improvised initiatives, festivals, and programs coordinated by an ever-renewing population of residents and guests. ↩

Vera Frenkel, “The New School of Art: Insight-explosions,” arts/canada Oct/Nov. 122/123 1968: 13-16. ↩

Vera Frenkel, “The New School of Art: Insight-explosions,” 13-16. ↩

A key source for information on radical education in and around Toronto at the time was This Magazine is About Schools, a periodical that Frenkel was familiar with and occasionally contributed to. ↩

Emmett Hall, Lloyd Dennis, and Provincial Committee on Aims and Objectives of Education in the Schools of Ontario, Living and Learning (Toronto: Publications Office, Department of Education, 1968). ↩

Re-Thinking Education: The proceedings of a conference on the report of the provincial committee on aims and objectives of education in the schools of Ontario, Living and Learning (Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, 1969) 44-45. ↩

Former OCA teacher Morris Wolfe has published a detailed account of this era at the school in OCA 1967-1972: Five Turbulent Years (Toronto: Grub Street Books, 2001). ↩

All of Fuller’s designs were predicated on a set of forty “strategic questions” ranging from “Has man a function in universe?” to “What is ‘truth?’” Buckminster Fuller, Utopia or Oblivion: The Prospects for Humanity (Toronto, New York, Bantam Books, 1969). ↩

Edward A. Shanken, “From Cybernetics to Telematics: The Art, Pedagogy, and Theory of Roy Ascott,” Telematic Embrace: Visionary Theories of Art, Technology, and Consciousness, ed. Edward A. Shanken (Berkeley: University of California, 2003) 40-41. Toffler also notably foresaw the germination of the experience economy resulting from the global redistribution of production (dubbed deindustrialization) and migration of consumerism from material goods to psychological and affective registers. Alvin Toffler, Future Shock (New York, Bantam Books, 1990) 219-237. ↩

R. Murray Schafer, “Cleaning the lenses of perception,” arts/canada Oct/Nov. 122/123 (1968): 10-12. ↩

Hugh Johnston, Radical Campus (Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 2005) 244-248. ↩

Harley Parker, “New Hall of Fossil Invertebrates Royal Ontario Museum,” Curator: The Museum Journal 10.4 (December 1967): 284-296. ↩

“Surely, somewhere in the world a museum can be built which, while conserving the past, will use that past to illuminate the present and the future; which will involve the young people as completely as television; which will make present sense of centuries of collecting.” Parker, “New Hall of Fossil Invertebrates Royal Ontario Museum” 296. ↩

“The Museum as a Communication System,” Curator: The Museum Journal 6.4 (October 1963): 358. ↩

“The Museum as a Communication System,” Curator: The Museum Journal 6.4 (October 1963): 351-352. ↩

For a discussion of Parker’s model see Adam Lauder, “Executive Fictions: Revisiting Information,” MA thesis, Concordia University, 2010: 55-57. ↩

Parker, “New Hall of Fossil Invertebrates Royal Ontario Museum” 296. ↩

Michael McClelland and Graeme Steward, Concrete Toronto: A Guidebook to Architecture from the Fifties to the Seventies (Toronto: Coach House Books, 2007) 32. ↩

This became all the more pronounced in the later years as Rochdale adopted its own security force and played host to a robust set of drug sale and distribution operations. For a discussion of Rochdale as a separate and defensible enclave see Stuart Henderson’s “Off the Streets and into the Fortress: Experiments in Hip Separatism at Toronto’s Rochdale College, 1968–1975”. ↩

Sharpe, Rochdale, 20. ↩

Sharpe, Rochdale, 28-34. For more on the building and residents reactions to it see Mietkiewicz and Mackowycz, Dream Tower, 14-15. ↩

The Daily masthead was prone to permutations, sometimes appearing as the Tuesdaily, Mondaily, The Daily Planet amongst others. ↩

Once a resident of Rochdale College and designer working with Coach House Press, here Bronson writes in retrospect of the importance of underground publishing in the late 1960s as a necessary communicative tool and support for a burgeoning artist-run culture in Canada. AA Bronson, “The Humiliation of the Bureaucrat: Artist-Run Spaces as Museums by Artists,” From Sea to Shining Sea: Artist-Initiated Activity in Canada, 1939-1987. Eds. AA Bronson, et al. (Toronto: Power Plant, 1987). ↩

Image Nation, 15 April 1969. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 0013 Box 9. ↩

Daily, n.d., Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 9. ↩

Coupland, accompanied by Coach House Press’s Stan Bevington, conduced an exhaustive survey of Toronto area restaurants and their interior design, documenting and measuring classic booth designs. The Press later reprinted at least one of these photographs as a postcard. ↩

A reminder of this presentation can be found in the Daily, 29 September 1968. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 9. ↩

Image Nation, 3 March 1969. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 0013 Box 9. ↩

Daily, c. December 1968. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 9. ↩

Daily, 2 December 1968. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 9. ↩

Daily Planet, 20 January 1969. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 9; council minutes published and circulated in June indicated that the restaurant was expected to make $60 000 in revenue, Council Meeting, 20 June 1969. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 13. ↩

Daily, 2 December 1968. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 9. ↩

Daily Planet, 20 January 1969. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 9. ↩

Rochdale supplement, 1 March 1969. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 9. ↩

Mondaily, 3 March 1969. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 9. With Wu’s arrival came a slight increase in menu prices, although a 25% discount was available to all members (otherwise registered Rochdale residents). Wu is simply referred to by this single name throughout the College’s periodicals as well as its two published histories (Sharpe; Mietkiewicz and Mackowycz). Prior to Wu’s arrival Art Roberts managed the restaurant. ↩

Alan Edmonds, “The New Learning: Today it’s Chaos / Tomorrow…FREEDOM?,” Maclean’s, May 1969: 70. ↩

AA Bronson, personal interview, 4 August 2009. ↩

Council Meeting, 20 June 1969. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 13. ↩

Daily, [c. 8 September 1969]. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 13. ↩

Daily, c. 8 September 1969. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 13. ↩

Daily, 30 September 1969. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, T-10 00013 Box 13. ↩

Sharpe, Rochdale, 163-64. ↩

Tracy McCallum, “Editorial from a Hip (non) Capitalist,” Canadian Whole Earth Almanac (Spring 1971): n.p. ↩

Rayner Banham, Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past (New York: Harper & Row, 1976). ↩

See Felicity D. Scott, Architecture or Techno-utopia: Politics After Modernism (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007). On Archigram see Simon Sadler, Archigram: Architecture Without Architecture (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005). On Constant’s New Babylon see Tom McDonough, “Metastructure: Experimental Utopia and Traumatic Memory in Constant’s New Babylon,” Grey Room 33 (2008): 84–95 and Simon Sadler, The Situationist City (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999). On Cedric Price’s Fun Palace see “Cedric Price: Fun Palace,” Canadian Centre for Architecture, 28 April 2011 <http://www.cca.qc.ca/en/collection/283-cedric-price-fun-palace> and Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Cedric Price (Köln: Walther König, 2010). For contemporary sources in addition to Banham’s study, see Michel Ragon, Histoire mondiale de l’architecture et de l’urbanisme modernes, vol. 3: Prospective et futorologie (Tournai: Castermann, 1971) and Justus Dahinden, Urban Structures for the Future (New York: Praeger, 1972). ↩

Bronson recalls that he and Coupland “were both well-versed in such arcane delights as Archigram” and that this interest held noticeable influence over Coupland’s designs. E-mail to the author, 1 February 2010. Junkigram! was produced in collaboration with Clive Russell. Christina Ricci notes that in addition to its obvious synonymy with Archigram the publication also drew inspiration from architects Alison and Peter Smithson and the Independent Group, in particular their 1956 exhibition This Is Tomorrow that famously marked the emergence of pop art. While the publication was published by the University of Manitoba School of Architecture these architects and events were not included in its curriculum, Bronson and Russell gleaned this information from their own independent learning. Christina Ricci, “Illusions, Omissions, Cover-Ups: The Early Days,” The Search for the Spirit: General Idea 1968-1975 (Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 1997) 14. I believe the same argument can be made for Coupland’s case, in that his technique was honed through study at the University of Toronto but the conceptual underpinnings of his designs were acquired outside of its curriculum. Ricci’s perceptive identification of Alison and Peter Smithson is also apt for Coupland, considering the duo’s central importance to the advent of Bruatalism and Pop Art, a genealogy to which Coupland, I argue here, attempted to foreground. For more on the work of Alison and Peter Smithson and the Independent Group see: Claude Lichtenstein and Thomas Schregenberger, eds., As Found: The Discovery of the Ordinary (Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2001) and The Independent Group, spec. issue of October 94 (2000). ↩

Banham, Megastructure, 133-139. ↩

Banham, Megastructure, 132. ↩

See my text “Let The Buyer Beware,” A Play to be Played Indoors or Out: This book is a Classroom, eds. Corinn Gerber, Lucie Kolb, Romy Rüegger. (Zurich: Passenger Books, 2012). On changing economics of Canadian universities, see James Turk, ed, Corporate Campus: Commercialization and the Dangers to Canada’s Colleges and University (Toronto: James Lorimer and Company, 2000). ↩

See the aforementioned article by Stuart Henderson as well as his book Making the Scene: Yorkville and Hip Toronto in the 1960s (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011). ↩

Inderbir Singh Riar, “Montreal and the Megastructure, Ca 1967.” Expo 67: Not Just a Souvenir, Eds. Kenneally, Rhona Richman and Johanne Sloan (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010) 197-198. On participation see also, Jonathan Hughes and Simon Sadler, eds, Non-Plan: Essays on Freedom, Participation and Change in Modern Architecture and Urbanism (London: Routledge, 2013) and Fred Turner, The Democratic Surround: Multimedia and American Liberalism from World War II to the Psychedelic Sixties (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). Expo 67 and other structures in Montreal also figure prominently in Banham’s study. ↩

Anthony Vidler, “Diagrams of Utopia,” The Activist Drawing: Retracing Situationalist Architectures from Constant’s New Babylon to Beyond, eds. Catherine de Zegher and Mark Wigley (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2002) 84. ↩

“The Meanest Girl in Town” was published and syndicated by Gospel Publishing House in Springfield, Montana. The comic follows Opal a teenage girl who bullies her good Christian friends only to later follow their example of forgiveness and prayer. ↩

Article: Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported License.

Image: "In Sit You" by Jennifer Marman and Daniel Borins. Used with permission.