The room was dark as ebony. █████████ started playing a track very loudly — I mean very loudly. The song was, “Let the bodies hit the floor.” I might never forget that song.

-Mohamedou Ould Slahi, Guantánamo Diary1

Our image ████████████ █████████ dominion

-Philip Metres, Sand Opera2

In short, the thesis of this book is ███████████.

-Craig Dworkin, Reading the Illegible3

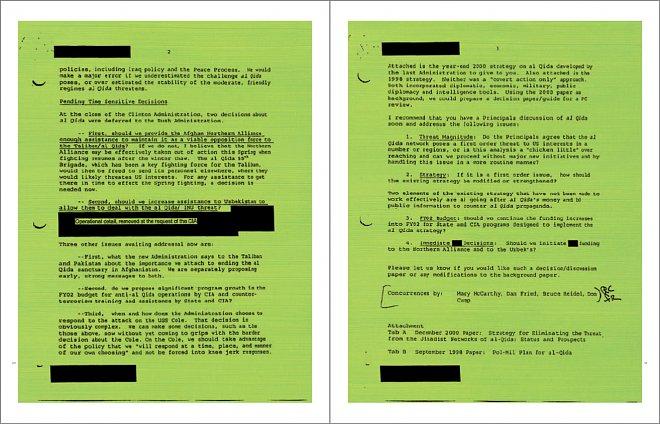

In January 2015 Mohamedou Ould Slahi published his Guantánamo Diary in twenty-two languages worldwide. The Mauritanian national began writing the memoir in his cell shortly after meeting with his attorneys in 2005. How exactly the heavily redacted document was released in its present form is not entirely known, since all communications by detainees at the prison are subject to automatic censor. We do know that his attorneys first underwent a legal battle to gain access to an unclassified version of the document; the manuscript was then subject to clearance by a Pentagon “privilege review team,” after which further negotiations were made for its public disclosure. The memoir tells a story consistent with many former detainees: abducted by the CIA and rendered to a prison in Jordan in late 2001, Slahi was then taken to a black site known to its inmates as the “Dark Prison” north of Kabul, Afghanistan, before subsequent transfer to Guantánamo Bay’s infamous “Strawberry Fields” compound for high-value prisoners (known as “ghost detainees”).4 At the time of the diary’s publication, Slahi will have been held without charge by the U.S. government for more than thirteen years.

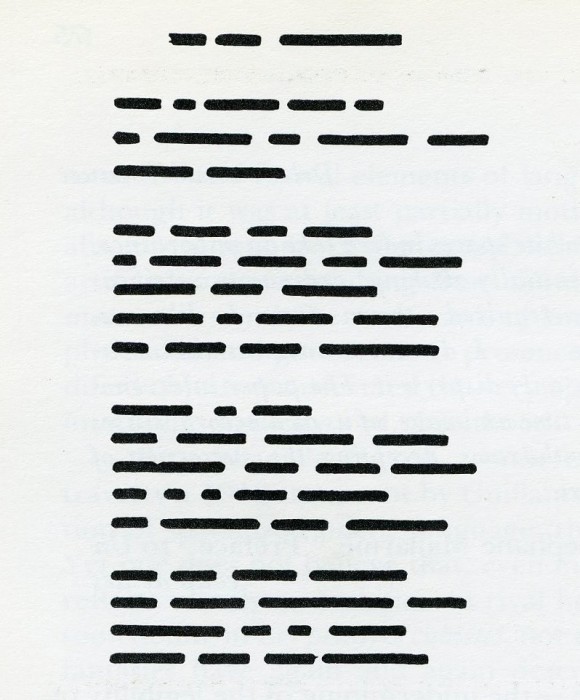

“During my time with █████████,” Slahi recounts of one official who interrogated him late in 2005, “many poems went across the table.” His interrogator’s verses, recalls Slahi, were far too “surrealistic,” admitting he is “terrible when it comes to surrealism. I hardly understood any of her poems.”5 He did not keep his interrogator’s work, but dutifully included one of his own in the diary. The poem’s eighty-six lines are redacted in full, and hence opaque in an altogether different sense:

One of my poems went

██████████████████████████████

█████████████████████████████████

█████████████████████████████████

█████████████████████████████████

█████████████████████████████████

█████████████████████████████████

……………………………………………………………………………………………….

-Slahi, GTMO6

This was not the first time a prisoner at Guantánamo published his poetry. In 2007, law professor Marc Falkoff published a small collection, Poems from Guantánamo: The Detainees Speak, having undertaken a herculean effort in negotiations with Pentagon review teams that first classified the poems as a national security threat, according to its editor.7 Slahi’s poem, however, is no doubt the first to appear in print fully redacted. In fact, only one passage from the memoir is more strictly classified (an episode recounting a December 2003 interrogation). Slahi’s editor Larry Siems explains that the 466-page handwritten manuscript was edited twice: “first by the United States government, which added more than 2,500 black-bar redactions, … and then by me.”8 He first saw the manuscript in 2012, at which time other documents related to Slahi’s case had entered the public record. Siems went to work cross-referencing Slahi’s account of his detention with Justice Department and Senate Armed Services Committee reports that also documented his interrogation. Read together, these documents trouble the very classification procedures designed to conceal incriminating evidence implicating state actors. Thus, Siems quickly learned: “redactions are like the fingerprints of that longstanding censorship regime.”9

Some editors might have excised the redacted passages given their supposed illegibility. Instead, Siems chose to keep them intact, creating for readers a visually disorienting book that incorporates into Slahi’s memoir the menacing effects of state censorship and surveillance. For New York Times reviewer Mark Danner – in addition to Dostoevsky, Beckett, and Kafka, the literary spirits “looming over these pages” – it is the U.S. intelligence agents’ “pitch-black” redaction marks that make this a “dark masterpiece.”10 The “final” installment of the Guantánamo Diaries features many hands: Slahi’s of course, Siems’s, and an untold number of editors working for the CIA and the Information Security Oversight Office (ISOO). Readers must therefore negotiate these marked deletions in terms of the institutions that frame processes of reading, linguistic materiality, cultural translation, and especially the subjects who shape and are shaped by these practices.

The purpose of this inquiry is two-fold. First, we will consider how to read the material mark of the redacted line – that is, to track how this specific form of censorship came to be the preferred tool of military intelligence agencies – and how we might read redaction within and against the attendant legal and bureaucratic protocols specific to the discursive apparatus it produces and maintains. I will argue that redaction shares a complex symbolic economy of meaning with black ops, black sites, and black budgets, terms that name unacknowledged acts of extrajudicial state subterfuge and violence, perpetrated under a veil of secrecy and impunity, carried out with the aid of corporate actors, and a well of near-limitless funds. This symbolic economy (attendant to the aforementioned military apparatus) ultimately conceals, more often than not, the surveillance and punishment of black and brown bodies coming into purview of its optical sites.11 The point then is to disrupt and trouble these markings – specifically where they operate in the State’s official history of records – by confronting the censorial regime’s exercise of power over representations of war.

The second aim of this inquiry is to offer an account of an emergent poetics that counter-inscribes the redacted page and its pernicious cultural logics. Jenny Holzer’s Redaction Paintings, Trevor Paglen’s redacted geographies and “Black Site” maps, and Philip Metres’s Sand Opera will afford exemplary case studies. Yet, a unique form of documentary closer to “counter-forensics” (Eyal Weizman’s term)12 than to a poetics of witness has unfolded over the course of the twenty-first century – among poets, artists, and filmmakers like Mark Nowak, Mariam Ghani, Claudia Rankine, Wafaa Bilal, Noor Behram, Carlos Soto-Román, Critical Art Ensemble, Rachel Zolf, Harun Farocki, Precarias a la Deriva, Gulf Labor, Hasan Elahi, Caroline Bergvall, Nonny de la Peña, Sang Mun, Simon Denny, Stephen Collis, Institute for Applied Autonomy, Commune Editions, Mark Lombardi, Forensic Architecture, Judith Goldman, Jordan Abel, Jena Osman, Amy Sara Carroll, Adam Dickinson, Lisa Robertson, Nick Thurston, Paula Levine, Kim Rosenfield, Ed Steck, and Laura Kurgan. They create a form of tactical art so-called by assembling together documentary, erasure, lyric, maps, digital tools (e.g. GPS, GIS, API), diagrams, the essay, and other poetic (and non-poetic) ad-hoc forms of research-driven artistry fixated on the paper trail left in the wake of conflict.

███████ ███ ███████

To redact means “to conceal from unauthorized view; to censor but not to destroy.” Its original sense – “brought together in a written form,” to organize, compile, and arrange – appears almost opposite its present-day meaning. Redaction criticism names a critical method of Biblical scholarship whereby the author is an editor (“redactor”) of her source materials. In this sense, then, to redact is to edit. Its operative logic is secrecy rather than negation, drawing a dividing line between the few with special providence over clandestine knowledge and the public at large subject to the machinations of such power by varying degrees. Its most common synonym is to “sanitize” (“clean up, as by the removal of undesirable, improper, or confidential material”). Yet a further entry should give the reader pause: “of a material thing reduced to ‘ashes’ (‘redacte into duste’),” and in its verb form “to reduce (a material thing) to a certain form, esp. as an act of destruction.” Hannibal, we are told, “let Carthage be demolished and redacted to ashes.”13

There are many ways to inscribe illegibility. Ronald Johnson’s radi os (1977), Jen Bervin’s Nets (2003), Brian Dettmer’s Book Autopsies (2005-), and M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! (2011) have ostensible similarities in form and method. Yet their techniques – strike-through, deletion, cutting, elision, and so on – signify according to very different cultural contexts and meanings that highlight, in turn, various processes of reading, regimes of censorship, satiric commentaries, and linguistic materiality.

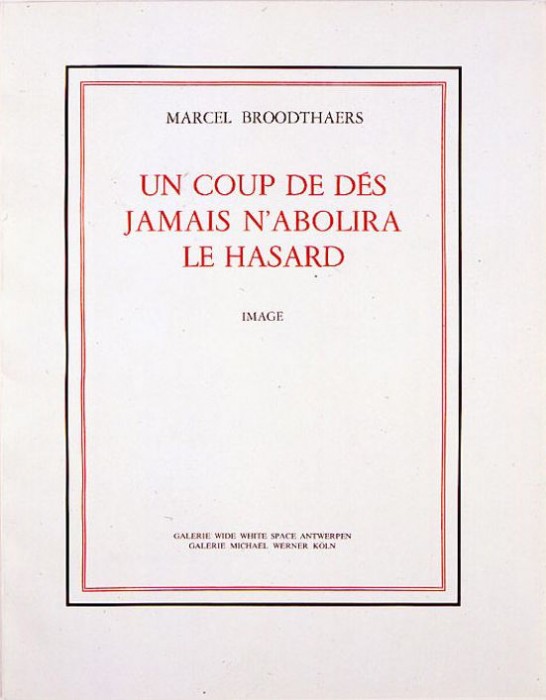

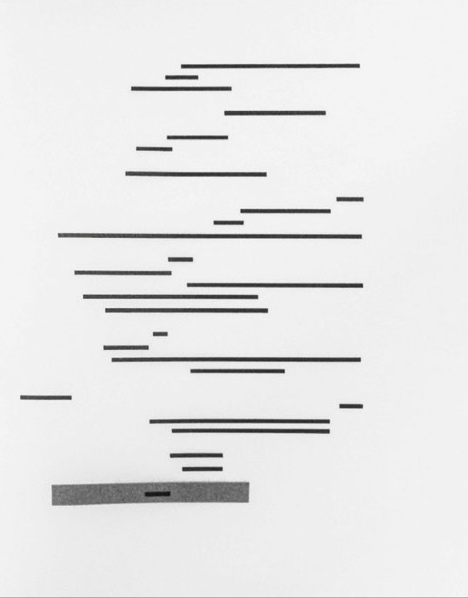

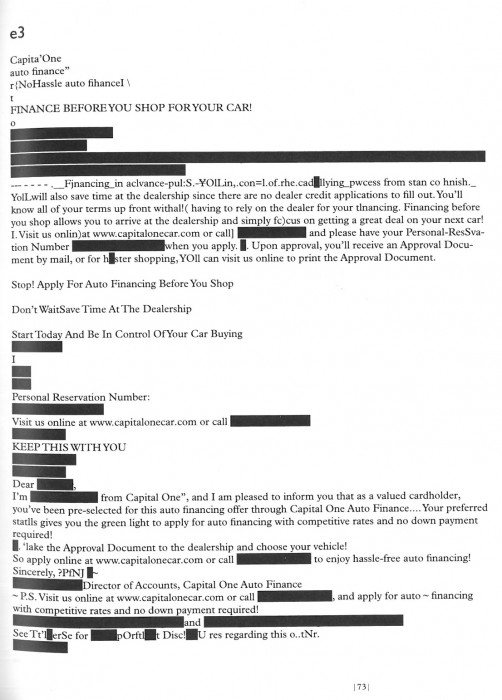

In 1969 Marcel Broodthaers produced an edition of Stéphane Mallarmé’s Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (“A cast of the dice will never abolish chance”), replacing every line in the poem with solid black bars of equivalent length. The artist also substituted the word “(Image)” for “Poème” in the book’s front matter, having translated the French modernist’s 1887 masterpiece into clean, geometric abstraction. Broodthaers said of Mallarmé that he was the chief source of contemporary art, having “unwittingly invented modern space.”14 Craig Dworkin avers that Broodthaers’s schematic edition is no “mere reduction.” Instead, “(image) is more a logical extension of Mallarmé’s poetics, recognizing not just the obvious fact that Un coup de dés is a visually marked poem with a unique significant layout, but that Mallarmé’s work was predicated … on the materiality of the letter.”15

Image 1-2: Marcel Broodthaers, Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hazard (“A cast of the dice will never abolish chance”), Illustrated Book with Lithographs, MOMA, 1969.

Broodthaers produced three versions of Un coup de dés. The second featured a bound book of translucent paper; ethereal in effect, the black bars appear to hover in the air. In the third version, Broodthaers does away with the codex form altogether, replacing the bound book with a series of aluminum plates. If Mallarmé had sought to liberate language from the typographic and formal restrictions of the conventional book, experimenting with multiple typefaces spread across the page, then Broodthaers extended this project to include the material page itself.

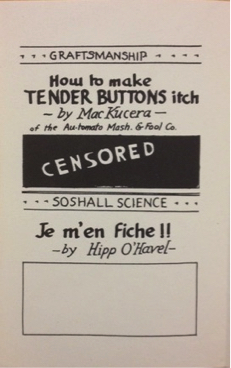

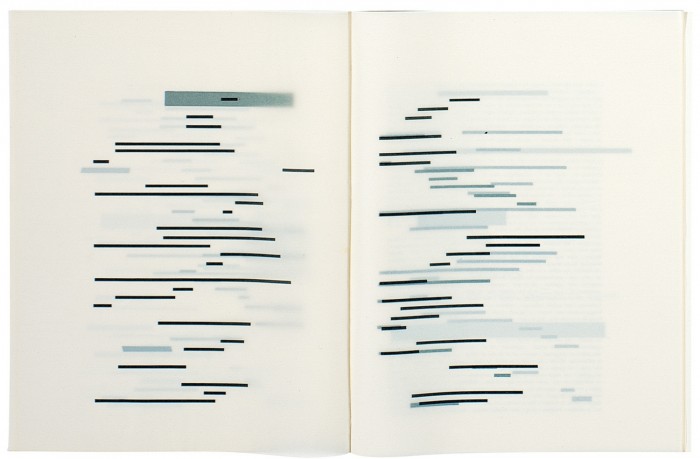

Ezra Pound, Kurt Schwitters, Raoul Hausmann, Bob Brown, and Man Ray comprise a shortlist of poets and artists who use the iconic black markings decades before Broodthaers had done so. In every one of these cases the purpose was to satirize the censorship of obscenity. Brown, for instance, remarks, “HA! HA! The ███ ███ ███! Censor it if you must. Say: ‘The ███ ███ ███! The black blot of the censor makes anything innocent seem most reprehensible. Efficiently censored the classic tome entitled “The Winged ███ ███ ███” might be mistaken for “The Winged Victory.”16 The grateful “compiler,” Brown remarks in the preface to Gems: A Censored Anthology, could not have created this work “without continual reference” to the texts of Wordsworth, Longfellow, Tennyson, and others, which “have sustained his inspiration at the high pitch needed in successful censorship.”17 The volume was published in 1930, in the wake of the “Clean Books” crusade spearheaded by the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice.18 Craig Saper remarks in his poignant introduction to Gems (reissued for the first time in 2014), “[t]o hang the ███ ████ sanitizers by their own ███████ was the vanguard tactic that Brown employed repeatedly.”19

Image 3: Bob Brown, Gems: A Censored Anthology, ed. Craig Saper (New York: Roving Eye Press, 2014), 63.

Marginal and obscure as such experiments may seem, consider that Brown’s premise echoes Annabel M. Patterson’s trailblazing Censorship and Interpretation: The Conditions of Writing and Reading in Early Modern England (1984), in which she argues that it is largely due to censorship that we “owe our very concept of ‘literature,’” that the “functional ambiguity” upon which figurative codes of communication developed, did so in order to negotiate and circumvent potentially “hostile and hence dangerous readings of their work.”20 For Brown and Patterson alike, symbolic language evolves and maneuvers through a gauntlet of repressive gag orders.

These two lineages – the typographic production of modern space and the protocols of censorship – are dialectically driven rather than mutually exclusive. By the time Broodthaers produced his editions of Un coup de dés in 1969, the same black marks used to police obscenity had become inexorably linked to forms of bureaucratic state and corporate “representability”21 arising with the advent of the World Wars, the subsequent Cold War, and now the War on Terrorism. The classification of wartime correspondence presents one facet of this complex history of military surveillance, while cryptography and the emergence of digital telecommunications has expanded the technical scope, systematization, and control of knowledge production. The horizontal black bar, like Thomas Pynchon’s “Byron the Bulb,” is present in the background of western twentieth-century history – in memos, reports, correspondence, black-box recordings, metadata entries, and satellite imagery.

Redaction forms the surreptitious underbelly of what Lisa Gitelman in Paper Knowledge calls the “media history of documents.” Literary studies tends to focus on the mimeograph’s pivotal role in self-publishing during the post-WWII decades. Poets associated with the Beats, Black Mountain College, the San Francisco Renaissance, Black Arts, the New York School, and radical Feminism, along with early science-fiction fanzines depended upon this comparatively inexpensive form of analogue duplication. Notably, the xerox revolution was also underway. Photocopying was in the beginning at least the province of state functionaries, inseparable from bureaucratic protocols and practices, which form an essential part of the cultural politics of the Cold War. In plain terms, the instant duplication of sensitive records prompted a wave of policy reforms designed to secure, classify, and control information. Gitelman’s book is especially edifying where little-known facts about xerography inform well-known historical events. Take the Pentagon Papers, for instance. In the same year Broodthaers made his first copy of Un coup de dés, Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo, both employees of the RAND Corporation, began to photocopy installments of the forty-seven-volume report, secretly completing their work after-hours at the workplace of a sympathetic friend. Known then by its comparatively banal official title, “History of U.S. Decision-Making Process on Vietnam Policy,” Robert MacNamara had commissioned the report in 1967 as Secretary of Defense, enlisting thirty-six authors whose identities remained intentionally anonymous (presumably to protect their reputations at the Pentagon). Gitelman rightly observes that the Pentagon Papers seemed to have “sprung from a giant five-sided filing cabinet. And the filing function, unlike the author function, organizes documents rather than classifies discourse.”22 The Pentagon Papers would appear in three separate editions published by the New York Times, the Beacon Press, and the Government Printing Office, each one featuring its own distinct contents, drafts, appendixes, and the like.23 However prosaic the activity may seem, Gitelman insists that xerography is “an unacknowledged form of cultural production, a form of making, remaking, and self-making that was framed in part by the always emergent bureaucratic norms of statecraft and citizenship.”24 We might dote on the choice of words here to ponder the “unacknowledged xerographers” of the world. The age of mechanical document duplication that produced the modern office drone also produced the modern whistleblower – who, after all, is a subversive copy-maker.

The 1966 Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) mandated partial disclosures of government documents, procedures for said disclosures, along with key exemptions such as executive orders pertaining to national defense, trade secrets, “inter-agency memoranda,” and some law-enforcement records. Following a wave of scandals, chief among them Watergate and the Pentagon Papers, Congress passed amendments to the FOIA in 1974 to cover CIA and FBI records. (Notably, Gerald Ford unsuccessfully vetoed the measure on the advice of his then chief-of-staff Donald Rumsfeld and deputy Dick Cheney).25 Subsequent access to FBI records revealed now infamous investigations of prominent individuals and organizations, including Martin Luther King Jr., Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, John Lennon, the Communist Party, W.E.B Du Bois, the Southern Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the NCAAP, and others. The release of CIA files similarly uncovered covert operations in Iran, Guatemala, Cuba, Chile, and Nicaragua. Athan G. Theoharis and James X. Dempsey are among countless historians who argue that access to these agency records were indispensible if historians were to document and analyze government surveillance at home and in U.S. interests abroad.26 In the wake of these revelations, political leaders and agency officials have worked diligently to annul or limit key aspects of the FOIA. Shortly after the Pentagon Papers surfaced, President Nixon issued an executive order creating the Interagency Classification Review Committee in 1972, which was later replaced with the Information Security Oversight Office by the Carter Administration in 1978. Housed today in the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), this office is tasked with standardizing policies of document classification and advises the president on matters of information security. A detailed account of this protracted legislative history is beyond the scope of this paper, but suffice it to state here it continues to serve as a battleground between information activists and intelligence agency officials.

In March 2015, The Associated Press released a comprehensive study of federal data pertaining to the FOIA, concluding that the Obama administration has set a record for censorship since the legislation was enacted in 1967. Among its key findings:

- the government took longer to release documents (if at all) than any previous administration. The backlog at year’s end grew by 55 percent to more than 200,000 requests;

- it cut 375 full-time employee jobs tasked with locating records;

- one in three cases in which claimants appealed decisions to withhold or censor records were done so improperly;

- the White House spent $28 million in lawyers fees to keep documents secret;

- and it set a record by censoring or denying access in 250,581 cases (or 39 percent) of total requests. Additionally, in 215,584 instances the government could not locate records,

- the claimant could not pay the copy fee, or the government found the request “unreasonable” for unspecified reasons.27

Another statistic is also telling: 714,231 FOIA requests in 2014 mark an all-time high. Mirroring a wave of scandals during the late-1960s and early 1970s that led to the Privacy Act Amendments of 1974, key disclosures by WikiLeaks, Chelsea Manning, Edward Snowden, William Binney, Thomas Drake, John Kiriakou, Jeffrey Sterling, and others have generated significant interest in the FOIA by activist collectives, journalists, academics, writers, and artists. Filing a FOIA request is made so intentionally difficult there are entire organizations dedicated to navigating its onerous agency-specific guidelines. The Electronic Frontier Foundation, the Federation of American Scientists’ Project on Government Secrecy, and George Washington University’s National Security Archive provide a range of essential resources. The last of these is an independent research institute and repository that publishes a highly instructive “How to File” manual, Effective FOIA Requesting for Everyone. The Freedom of Information Act request has apparently become a work of art in its own right.

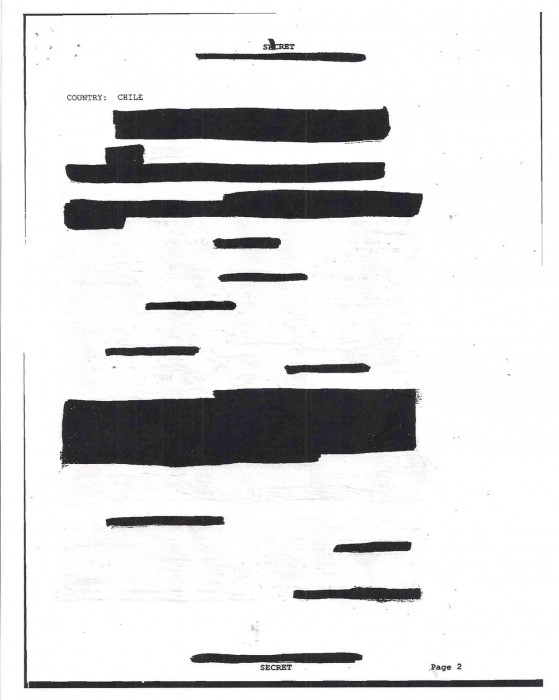

Image 7: Carlos Soto-Román, Chile Project [Re-classified], San Francisco, CA: Gauss PDF Editions, 2013.

Nevertheless, by the late twentieth century it would become virtually impossible to read aesthetic uses of redaction apart from the statecraft inaugurated during the Cold War and expanded during the War on Terrorism. In the summer 2001, Cabinet Magazine published work from Julia Meltzer and David Thorne’s Speculative Archive for Historical Clarification (SAHC), a project to examine state self-documentation.

Image 8: Julia Meltzer and David Thorne (The Speculative Archive), “ 1 in 32: The Culture of Secrecy,” Cabinet 3 (Summer 2001), 35.

Image 9: “The FOIA Process,” Effective FOIA Requesting for Everyone (New York: National Security Archive, 2008), 3.

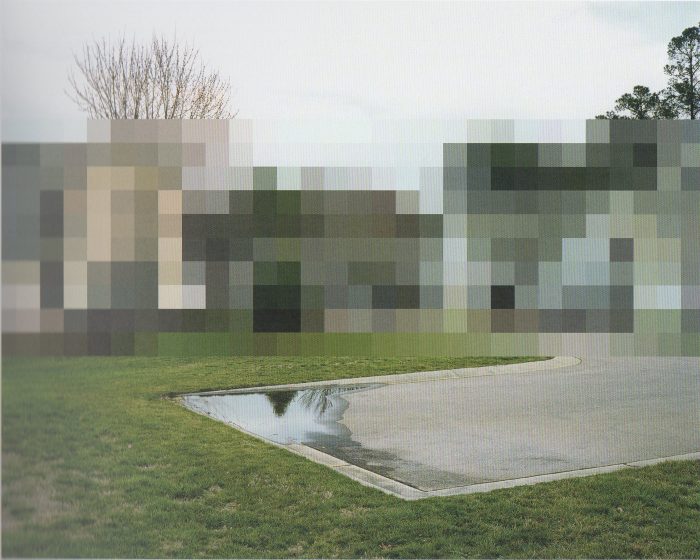

Image 12: Edmund Clark, “Untitled,” Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition, eds. Crofton Black and Clark (New York: Aperture, 2015), 141. “Redacted image of of a complex of buildings where a pilot identified as having flown rendition flights lives” (155).

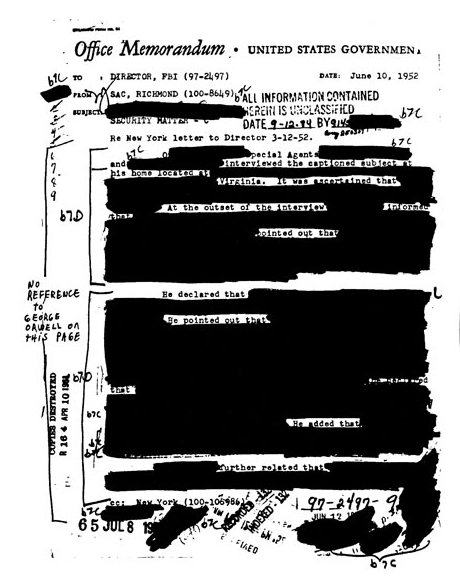

An unknown official tasked with document classification offers an unusual gloss: “no reference to George Orwell on this page.” The heavily redacted memo sent to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover is dated 10 June 1952, its subject matter a letter sent in March regarding an interview with an unnamed subject. The person in question cannot be Orwell, who died two years earlier in London and a year after the publication of 1984 (1949). The gloss, read both against the vague unredacted phrases (“he declared that,” “he pointed out that”) and Hoover’s campaign against alleged communists and other radicals during this period only serves to highlight Cold War paranoia. Although the redactor’s intentions remain unknown, comments by employees involved in classification protocols can be surprisingly candid. The Speculative Archive’s short film It’s Not My Memory of It (2003) contains interviews with information management officials, including Charlie Talbott, the Deputy Director of the Freedom of Information and Security Review, and Steven Garfinkel, the Director of the Information Security Oversight Office (ISOO). The latter remarks, for instance: “I call them protocol secrets, and that’s my own term … because they’re not really secret. Everybody knows that it happened, we just can’t admit that it happened… and there are lots of protocol secrets. They’re secret in the sense that they’re not admitted, so they’re not formally true. It’s just that everybody assumes that they’re true, and their assumptions are usually pretty correct.”28

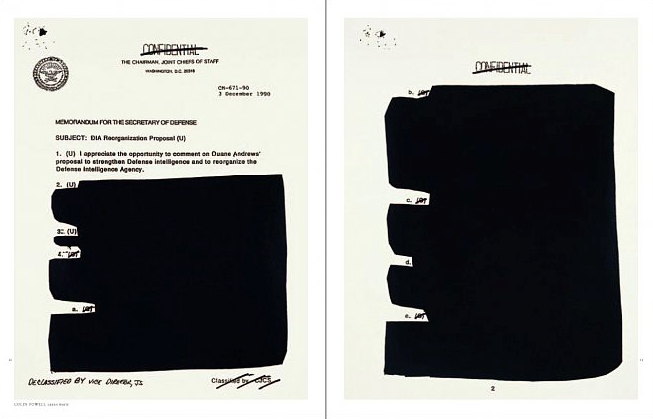

Jenny Holzer’s series of Redaction Paintings (2006) repurposes memoranda obtained through FOIA requests, many of which detail the justification for war in Iraq by top-ranking officials such as Colin Powell, Dick Cheney, and Donald Rumsfeld.

Image 13: Jenny Holzer, “Colin Powell – Green White.” Screen print, oil on linen, 33 x 76.5 in. Redaction Paintings (New York: Cheim & Read, 2006), 12-13.

Image 14: Jenny Holzer, “Memorandum for Condoleezza Rice – Green.” Screen print, oil on linen, 33 x 76.5 in. Redaction Paintings (New York: Cheim & Read, 2006), 20-21.

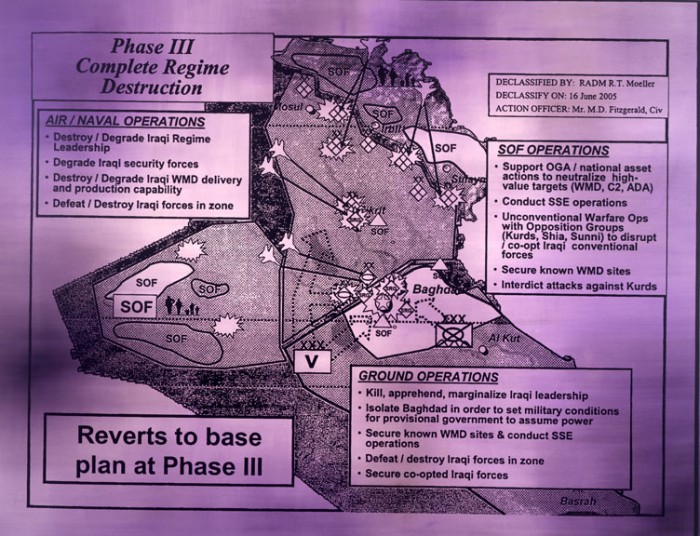

Recalling Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning, Holzer’s Redaction Paintings look like one of Robert Motherwell’s monochrome works painted over Joseph Kosuth’s concept art. Robert Storr concisely observes that Holzer’s work during the early 2000s engages with the U.S. government’s war on terror by way of the “patchwork of letterheads, standard forms, lists and, without irony, bullet points” that form the document history of warfare. “It is also a verbal maze of specialized terminology, acronyms, abbreviations, wrote salutations and initials” rendered intentionally opaque by “autocracy’s bunkered clerks.”29 PowerPoint diagrams used to brief President Bush and high-ranking officials on the United States Central Command’s plan for invading Iraq serve as a companion piece to the Redacted Paintings. Notably, the diagrams were made public via a FOIA submitted by the National Security Archive.30 Each features a mapped theater of operations31 in Iraq annotated with jargon-laced action items:

Image 15: Jenny Holzer, “Protect Protect.” Screen print, with oil on linen, 79 x 102.5 in. TATE, 2007.

Holzer’s choice to reproduce black and white documents in bright colors places these documents in dialogue with several of her most iconic works. From afar one might mistake them for Truisms or Inflammatory Essays (1978–1983), wherein iconic phrases like “war is a purification rite” ably mix with “complete regime destruction,” not to mention Rumsfeld’s “known unknowns” (whose clichéd sound-bytes were also the source text for appropriated poetry and an especially successful internet meme).32 The goals enumerated in these military slides promise to “deter Iraqi leadership from taking action against indigenous population, neighbors, and U.S.,” a four-phase plan in all with an approximate operations timeline of 200 days. In Holzer’s paintings it is the redacted line that becomes the consummate tautological aphorism.

By contrast, Mariam Ghani’s work is more research intensive. The Trespassers (2011) is a 105-minute video installation based on an archive of declassified internal reports, emails, memos, and legal briefs describing the interrogation of detainees in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Guantánamo – a portion of which is derived from FOIA requests obtained by the ACLU’s National Security Project. In the video, a magnifying glass highlights passages read simultaneously in English, Arabic, and Dari (an Afghan dialect of Farsi).

The Trespassers (excerpt) from Mariam Ghani on Vimeo.

Ghani elaborates, “[t]he translators have several different degrees of distance from the material: one is an Afghan only temporarily in the U.S., another a diasporic Afghan who formerly worked as a contract translator for the military, another an Iraqi who translated for Western journalists and was granted political asylum in the U.S. after being kidnapped by insurgents, and so on.”33 Moreover, the translators were encouraged to interpret the redactions they translated “based on their own inferences of what might belong in the blank spaces.” This polyphonic effect makes the video intentionally difficult to follow, replicating the ad-hoc contingency of real-time translation work. The effect also evokes the space of an interrogation room, “where important information is being volleyed back and forth between multiple codes and languages and no single person – not even the translator – fully understands everything that is going on.”34 In this way Ghani’s mise en scène of document production makes broader comment on the vast flows of fragmentary information culled, indexed, distilled, and labeled “Intelligence” by a battery of interrogators, translators, analysts, and policy makers. That which is lost in translation, whether by error, cultural bias, or disinformation, generates yet another form of redaction that spreads surreptitiously throughout the archive.

STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE

The speaker of Philip Metres’s “When I Was a Child, I Lived as a Child, I Said to My Dad” recalls an afternoon of play, then a day of work:

I turned back to the screen,

maneuvering pixilated tanks. Each arrow keyaltered trajectory, each cursor tap a tank blast. Fast-

forward two decades: in a cubicle outside Vegas,Jonah joysticks his predator above Afghanistan,

drone jockey hovering above a house on computer screen.35

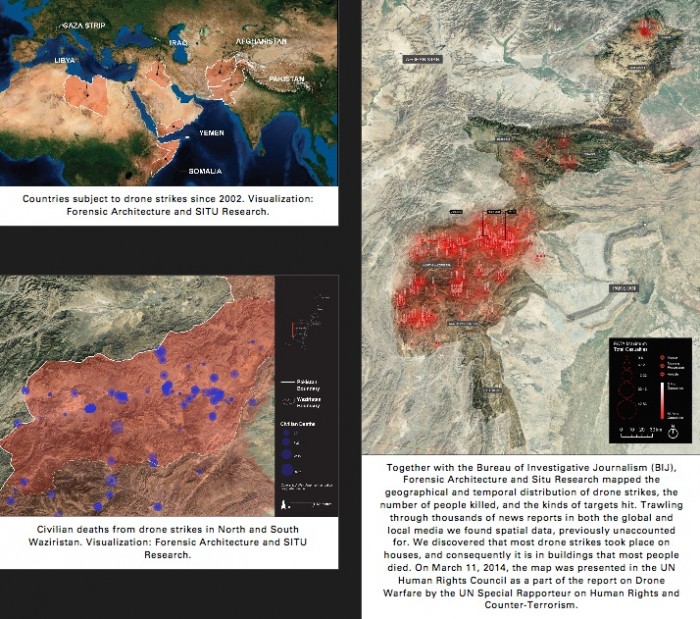

After the kill, Jonah “heads home. Pizza. Diaper rash. Removes a thumb / from his toddler’s sleeping mouth. Again no sleep … Our game’s / quaintly obsolete.”36 Numerous critics observe that Obama’s expansion of the CIA drone program makes redaction of prisoner testimonies moot. Thus, the drone wars ongoing in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia, Palestine, Iraq, and Yemen present a unique problem for journalism, activism, and just so a poetics of witness.

A terminological shift in descriptions of twenty-first-century warfare tells us a great deal about the “War on Terror,” and the justification for an expansionist project global in scale and endless in scope. Variations on this idea are numerous: Saskia Sassan speaks of a “multi-sited war,” Derek Gregory of “the everywhere war,” and for Jeremy Scahill, “the world is a battlefield.” Samir Amin terms the U.S. policy a “permanent war,” Mark Duffield an “unending war,” and for Dexter Filkins it is a “forever war.”37 Indeed, the “total wars” of the twentieth century are becoming protracted, borderless conflicts in the twenty-first.

On this point national defense strategists are hardly cryptic. Consider the “twenty-first century” defense objectives outlined in the Pentagon’s 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR).38 Its authors claim the U.S. must be ready to act on every continent from South America to Europe, the Middle East to South Asia. Nick Turse observes in “The Special Ops Surge” that since September 11, 2001, Special Operations forces “have grown in every conceivable way”:

Most telling, however, has been the exponential rise in special ops deployments globally. This presence – now, in nearly 70% of the world’s nations – provides new evidence of the size and scope of a secret war being waged from Latin America to the backlands of Afghanistan, from training missions with African allies to information operations launched in cyberspace.39

Turse reports that since the Bush Administration left office, Special Ops were deployed in approximately sixty nations; by 2013, according to Special Operations Command (SOCOM), elite forces such as Joint Special Operations Command were operating in 134 countries worldwide, accounting for a 123% increase during Obama’s presidency. William Hartung notes that while the Pentagon still maintains an enormous network of military bases, there has been a pronounced increase in its “‘rotational’ presence: training missions, port visits, and military exercises.” Indeed, “even as the size and shape of the American military footprint undergoes some alteration, the Pentagon’s goal of global reach, of being at least theoretically more or less everywhere at once, is being maintained.”40 The plan is a more permeable network of proxy armies designed to enforce American interests.

The CIA-led drone program comprises the other, more conspicuous, characteristic of the everywhere/anytime war. Several journalists, scholars, and organizations have already produced a sizeable body of research on drone warfare, including analysis of civilian death tolls and the psychological impact on affected populations; its place in the history of air combat and contributing advances in robotics, cinema, and geospatial technologies, surveillance, and reconnaissance; the lucrative business of drone manufacturing and its powerful political lobby, and remote warfare as a central theme in the dubious field of “military ethics.”41 I will discuss remote warfare in greater detail with regards to the groundbreaking work of Forensic Architecture and the photojournalism of Trevor Paglen and Noor Behram below, but suffice it to say for now that the systematic use of drones by the Bush Administration, just as with Special Ops forces, has greatly expanded under Obama’s presidential tenure. At present, surveillance and bombing campaigns are ongoing in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria, Iraq, Libya, Yemen, and Somalia, while Israel, too, has increasingly used drones to police the Palestinian territories.

And yet the “everywhere war” seems to play out everywhere else than the U.S. James Fallows observes that “as a country, America has been at war nonstop for the past 13 years. As a public, it has not. A total of about 2.5 million Americans, roughly three-quarters of 1 percent, served in Iraq or Afghanistan at any point in the post-9/11 years.” By contrast, as World War II drew near to a close, almost “ten percent” of the entire U.S. population was assigned to active duty – meaning a considerable number of “American families had at least one member in uniform.”42 This explains in part why the U.S. population fails to understand that Washington is a war state holding jurisdiction over much of the planet. Such is the difference between the total wars of the twentieth century and the permanent conflicts of the twenty-first. That is, both Fallows and Gregory are correct: the U.S. Military is simultaneously everywhere abroad and invisible at home.

Since the September 11th attacks, Intelligence spending by the nation’s sixteen spy agencies has grown exponentially. Moreover, the National Intelligence Program’s “black budget” for the 2013 fiscal year reached $52.6 billion.43 That is approximately 500 billion since the 2001 attacks. And while total Intelligence spending has been published since 2007 (after a successful FOIA request submitted by the Federation of American Scientists), disclosures by whistleblower Snowden reveal a great deal more about how the funds are allocated. The CIA, NSA, and National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) receive the lion’s share of this amount, while the National Geospatial-Intelligence Program (NGP) has grown by more than 100 percent since 2004. Among the chief duties for which they are charged, data collection, processing, and exploitation account for the largest portion of total spending. The report also indicates that the CIA and NSA have greatly expanded “offensive cyber operations” designed to hack foreign networks and conduct attacks on enemy states (Stuxnet being the most high profile example).44 The Washington Post reports that although its expense sheets provide no explicit breakdown of funds allocated for the CIA’s drone program, an item line titled “covert action programs” likely accounts for the “agency’s expanded paramilitary role, providing more than $2.5 billion … that would include drone operations in Pakistan and Yemen, payments to militias in Afghanistan and Africa, and attempts to sabotage Iran’s nuclear program.”45

By 2008, years before the Snowden revelations afforded greater clarity to the most recent annual black budgets, a small cadre of investigative journalists – among them artist and experimental geographer Trevor Paglen – were combing post-2007 declassified records just recently compelled by Congress. Historian R.J. Hillhouse and Paglen report that of the 2007 43.5 billion dollars spent on the National Intelligence Program, 70 percent went directly to private industry.46 This resource boon had transformed the CIA into a paramilitary force replete with a secret global prison system, an enhanced interrogation program, a fleet of drones, and a greatly expanded workforce comprised of private sector contractors.47

Beyond Washington’s monolithic architecture, “historical reference points to sculpt a national story about what it means to be an American,” and Paglen reads another ensemble of architectural texts “far subtler than the towering monuments and Doric columns” of the nation’s capital.48 “Hidden in plain sight” among Washington’s suburban sprawl are nondescript buildings and banal office parks, some of which house the largest intelligence agencies in the world along with a legion of contractors competing for their business. These agencies, Paglen contends, “are the monuments of the intelligence community, behemoth organizations occupying so much space they have freeway exits named for them.”49 Only the Pentagon’s iconic structure fits the ostentation appropriate for Washington; conversely, the post-9/11 funding boom produced an architecture indistinguishable from the private-sector office parks which house the contractors who increasingly drive public policy. To look at these structures, Paglen remarks: “it is not clear where the corporate world ends and the civic world starts.”50

After the Snowden disclosures, several major news affiliates still featured the same photograph of the NSA headquarters likely dating to the mid-1970s. In response Paglen sought “to expand the visual vocabulary we use to ‘see’ the U.S. intelligence community” by photographing the three largest U.S. intelligence agencies: the National Security Agency (NSA), the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA). “Although the organizing logic of our nation’s surveillance apparatus is invisibility and secrecy,” Paglen maintains:

its operations occupy the physical world. Digital surveillance programs require concrete data centers; intelligence agencies are based in real buildings; surveillance systems ultimately consist of technologies, people, and the vast network of material resources that supports them. If we look in the right places at the right times, we can begin to glimpse America’s vast intelligence infrastructure.51

Paglen intentionally chose to photograph the NSA Headquarters at night. Surrounding lights reflect off the black tint of the glass façade, making the spy agency appear – ironically – transparent. During the day, however, the building’s dark exterior is the architectural equivalent of the redacted black line. Perhaps also it wryly evokes a “black box,” the building a closed system device known only by its transfer characteristics, but whose inner-workings are unknown to its viewer.

Image 17: Trevor Paglen, “The Salt Pit, Northeast of Kabul, Afghanistan,” C-print, 24 x 36 in, 2006.

Paglen’s “experimental geography” shares common objectives with Mark Lombardi’s Global Networks (2003), Laura Kurgan’s counter-mapping projects (2006-), and Josh On’s They Rule (2001-).52 In Torture Taxi (2006) and Blank Spots on the Map (2009), Paglen meticulously traces CIA rendition flights to and from a network of secret prisons throughout the world. Paglen locates these sites using a combination of satellite imagery, a compass, testimony from former prisoners, and a range of cartographic techniques. “Although they were blindfolded, hooded, and shacked,” Paglen explains, “prisoners held who spent time at the Salt Pit consistently describe a ten-minute ride from the Kabul International Airport to the prison.” A former detainee, Khaled el-Masri, also provided a blueprint of the prison interior from memory. “If you draw a circle around the Kabul airport that represents the distance that one might travel in ten minutes, and compare that to el-Masri’s map, the Salt Pit jumps out at you.”53 The U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s own “Torture Report” (2015) would confirm these details nine years later.

Like Holzer’s Redaction Paintings and Paglen’s photographic series, we encounter in Metres’s Sand Opera an investigative poetics that similarly reads para-poetically – that is, beside or next to redacted lines in order to scrutinize the contexts that shape its concealed content. Metres’s title features a procedural constraint akin to Tom Phillips’s A Humument (a treatment of Victorian-era novel A Human Document), Ronald Johnson’s radi os (an erasure of John Milton’s Paradise Lost), and more recently, Jen Bervin’s Nets (an excision of William Shakespeare’s Sonnets). In Sand Opera, Metres redacts certain letters of the Camp Delta procedural manual for prison operations at the Guantánamo Bay Prison complex – hence, “Standard Operating Procedure.”54 Metres received a copy of the Standard Operating Procedure manual directly from a WikiLeaks affiliate years before Julian Assange’s organization received worldwide notoriety. The author then set to work on abu ghraib arias (2011), a chapbook whose cover page is made from old military uniforms as part of Chris Arendt’s Combat Paper Project, and which would later form the first section of Sand Opera.55 The title notably also alludes to Errol Morris’s eponymous documentary. Recent popular films dehumanizing Muslims like Zero Dark Thirty and American Sniper notwithstanding, even Morris chose only to interview American subjects for his film. Poet Fady Joudah calls this the “Oliver Stone syndrome”: “War stories and war poetry, far too often, valorize the soldier (or soldier-victim) at the expense of civilian-victims, who number about 90% of war casualties since the First World War.”56 Yet its source text, like the Pentagon Papers, also features an authorial presence closer to a “filing function” than an “author function”; despite instructions for detainee treatment that includes prevention of Red Cross meetings, Muslim burial instructions, and torture techniques, its language is often indistinguishable from the most banal policy documents. Metres’s counter-instruction thus involves a litany of written readings employing a variety of poetic forms and subjects.

Structurally Sand Opera is composed of two central operatic modes: arias and recitatives. This allows Metres to expand the poem’s testimonial impulses; “opera,” he explains in an interview with Alice James Books, “is always a multiplicity.” It is always “dialogic, polyvocal, polyphonic,” accommodating multiple voices and stories. Lyric, prose poetry, visual poetry, sound poems (for multi-voice), fractured sonnets, sestinas, diagrams, prayers, epigrams, heroic couplets, epistles, and other modes comingle, as do prisoner testimony, soldier interviews, redaction committees, and the voice of God. The poem’s testimonies converse within and against the bureaucratic procedures described in SOP and by the Director of the Information Security Oversight Office above Voices multiply to include many others who cope with the war from their different positions: for instance, the curator of the Iraq National Museum, an author of an Iraqi cookbook, an Arab American child playing a Gulf War video game, and lovers who identify their lovers’ bones.

Redaction serves as both a visual and a verbal device. Whereas modern and mid-century poets and artists like Brown and Broodthaers explore the visual possibilities of the censor’s black rows, for Metres the censor is one of several embodied subjects, to make present “the interference of an Editor … Homeland Security? The National Security Agency? Empire?”57 Consider the following passage:

In the Beginning I was there for 67 days of

██████████████████ I saw myself on the face

of the deep And the darkness he called Night

And Graner released

my hand from the door and he cuffed my hand in the back.

I did not do anything █████████████ hit me hard on my

██████████████████ cuffed me to the window of the room58

Grayscale adds yet another material dimension to the text’s innovative typography by registering the partially disembodied voice of the effaced. Public readings of the abu ghraib arias typically feature multiple participants from the audience, “one Editor, one Echoer, and one Voice of Genesis.”59 Directly evoking Elaine Scarry’s notion of pain, the theological concept of torture “requires an assault on the subjectivity of the tortured.” It is to strip not only dignity, but identity itself, from its victims. In this way,” Metres explains, “the Abu Ghraib Prison scandal began to resemble a perverse version of the Book of Genesis, in which God decreates Adam (one of the prisoners, of course, is A). Which is why I began to interpolate phrases from The Book of Genesis.”60 The role of the classified passage here is not to invite the reader to guess at a concealed content, but instead as a blank signifier to register torture’s gradual “decreation” of the subject.

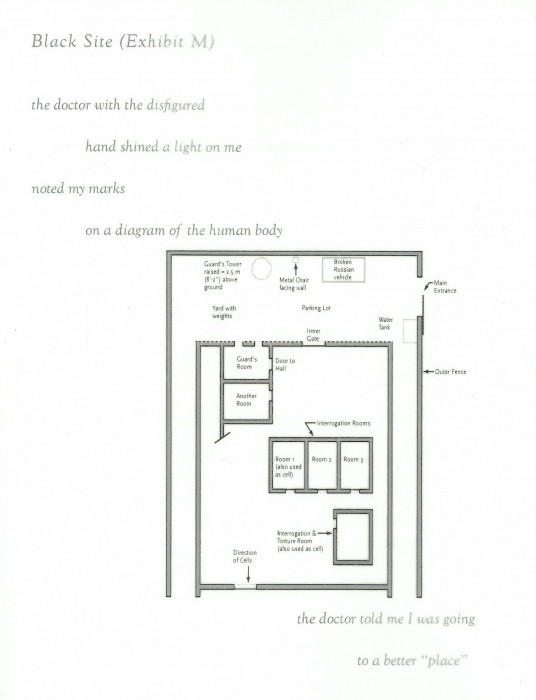

The final sequence of Metres’s volume, “Homefront/Removes,” is dedicated to Mohamed Farag Ahmed Bashmilah, a Yemeni national rendered, incarcerated, and tortured at the Dark Prison in Bagram, Afghanistan for more than eighteen months. Bashmilah is one of twenty-six prisoners formally recognized as being wrongfully detained, according to the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s (SSCI) report on torture.61

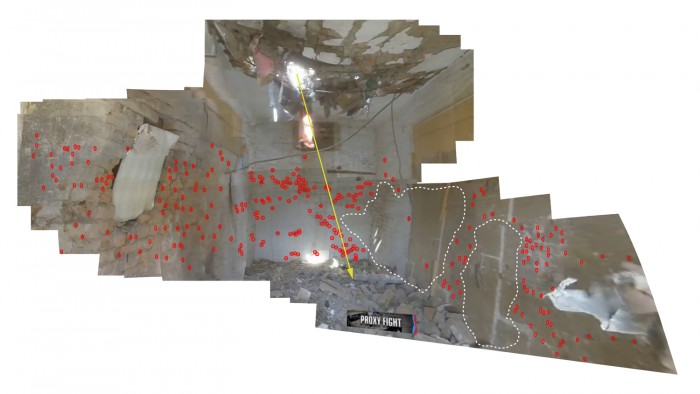

Image 19: Philip Metres, “Black Site (Exhibit M),” Sand Opera (Farmington, ME: Alice James Books, 2015), 71-3.

Pages alternate between Bashmilah’s testimony and fourteen-line prose poems, one of several irregular sonnet forms in the collection. Sand Opera also includes three of Bashmilah’s remarkably precise diagrams. One depicts his 9.5 x 6.5 foot cell at Bagram; a second diagram describes the interrogation room; and a third details the cellblock containing these rooms, a guard tower, and other adjoining structures. Each diagram is labeled “Black Site,” printed on semi-transparent vellum paper, overlaying a brief portion of Bashmilah’s testimony. A turn of the page creates a striking transposition, a mise-en-scène detailing Bashmilah’s confined material conditions and the prisoner’s subjective yet “disembodied I” lineated to highlight its affective lyricism: “The doctor with the disfigured / hand shined a light on me / noted my marks / on a diagram of the human body” (“Black Site [Exhibit M]” 1-4). “The doctor,” the speaker reveals, “told me I was going / to a better ‘place.’”62 Bashmilah was one of the first detainees to describe a CIA Black Site to Amnesty International officials. His account of conditions at the prison are consistent with several others allegedly held in Kabul, while Bashmilah’s reference to a “doctor[’s]” menacing words corroborates the allegations waged against American Psychological Association (APA) members who participated in CIA interrogations.63

Jordan Scott’s remarkable Clearance Process offers a similar examination of the military’s secretive prison system. In April 2015 Scott applied to U.S. Southern Command to visit the Guantánamo Bay Detention Center. Notably, he applied as a poet (rather than a journalist or an academic); consequently, officers at the camp were often uncertain how to classify his access status. Scott was given sporadic opportunities during highly restrictive tours of the prison complex to collect ambient sound recordings and to write poems and notes on his phone. At the end of each day, media personnel had to submit to an Operational Security (OPSEC) review where officers redact any “Operational Protected Information,” including transcribed sounds produced by “non-permissible human voice(s).” For Scott, the ambient sounds he collected “capture the room tone of a once-held violence or a never-heard pastoral … belong[ing] to the disappeared and the indefinitely detained.” Ambient recordings constitute “a kind of empty form that resonates with the visually-redacted photo or the lexically-redacted poem.” Indeed, redaction, Scott explains, “looks like ambience sounds. How can we listen to redaction? How can we listen to entire systems of it?”64

“The appetite for pictures showing bodies in pain,” writes Susan Sontag, “is as keen, almost, as the desire for ones that show bodies naked.”65 Thus Sontag’s last book, Regarding the Pain of Others, once again takes up a central theme in Of Photography, this time as the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq were fully underway. In Saidiya V. Hartman’s equally brilliant Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (1997), she inquires whether depictions of the tortured body incite indignation or merely “immure us to pain by virtue of their familiarity”: “[a]re we witnesses who confirm the truth of what happened in the face of the world-destroying capacities of pain, the distortions of torture, the sheer unrepresentability of terror, and the repression of the dominant accounts? Or are we voyeurs fascinated with and repelled by exhibitions of terror and sufferance?”66 Metres refuses to recirculate the Abu Ghraib photos for reasons consistent with Sontag and Hartman’s respective critiques. Like Paglen, Holzer, and Ghani, a central question informing Metres’s work is how to document without reproducing the terrible spectacle of suffering bodies? Instead, the diagrams, testimonies, manuals and reports overlay – like the book’s vellum paper – to form an architectural blueprint of systems that enable these acts of state-sanctioned violence.

The answer is most certainly not to sanitize war reporting or suppress evidence of war crimes. Photographs have a necessary place in the public record. But rather than further expose the victims of Abu Ghraib, and thus perpetuate the crime, Metres chooses specifically to document the acts of those who colluded in their torture and the acts of those who revealed and disseminated evidence of these abuses. The task for any documentary poetics is not to perpetuate the spectacle of black and brown social death, but rather to investigate critically the interpretive matrices in which the photographs circulate outside their original scenes, with the ultimate aim to intervene in this interpretive field, accounting for the ethical positions expressed by and between involved subjects and the structural oppression manifest in state institutions – both at home and abroad. Judith Butler argues that we must disrupt how war is “framed” in order that we may develop “disobedient acts of seeing.” What must be brought into view “is the staging apparatus itself, the maps that exclude certain regions, the directives of the army, the positioning of the cameras, the punishments that lie in wait if reporting protocols are breached.”67 Pair this set of claims with Fred Moten’s assertion that critical race studies provides a counter-frame to the logic of white supremacy found at the core of U.S. military policy. “What’s at stake,” Moten insists, “is fugitive movement in and out of the frame, bar, or whatever externally imposed social logic – a movement of escape, the stealth of the stolen that can be said, since it inheres in every closed circle, to break every enclosure.”68 Such is true of the structural logic underlying U.S. domestic and foreign policy.

“REDACTE INTO DUSTE”: THE BODY ██████████

In 2013, Forensic Architecture partnered with the Bureau of Investigative Journalism to produce detailed forensic studies of drone strikes carried out by the United States and Israel in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Palestine, Yemen, and Somalia.69 Led by Eyal Weizman, Forensic Architecture comprises a unique collective of architects, artists, filmmakers, and theorists who collaborate to reconstruct sites of conflict using an array of maps, geospatial data, satellite imagery, aerial footage, and digital modeling tools. Their purpose, Weizman explains, is to “gather and present spatial analysis in legal and political forums” that investigates the campaigns of States and corporate actors.

Image 20: Forensic Architecture, Bureau of Investigative Journalism, SITU Research, Geo-Platform, Forensic Architecture, 2013.

This fusion of witness account and spatial analysis is particularly important in a region of the world where social media is either unavailable or heavily censured. Authorities in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) enforce a strict siege on the region, forbidding entry to nonresidents and any circulation of recording equipment across its borders. In many instances, the information we have of the FATA comes from individuals like Noor Behram, a resident photo-journalist located in North Waziristan who documents the aftermath of drone attacks, including, for example, shrapnel used to identify makers of hellfire missiles and other ballistic evidence.

Image 21: Noor Behram, recovered fragment of AGM-114 Hellfire Missile; Presented at Lahore Arts Festival, “Bugsplat Week,” October, 2011. Republished in Spencer Ackerman, “Rare Photographs Show Ground Zero of the Drone War,” 12 Dec. 2011.

Image 22: Noor Behram, Datta Khel, 13 Oct. 2010. Presented at Lahore Arts Festival, “Bugsplat Week,” October, 2011. Republished in Spencer Ackerman, “Rare Photographs Show Ground Zero of the Drone War,” 12 Dec. 2011.

Image 23: Forensic Architecture, Bureau of Investigative Journalism, SITU Research, Case study no. 3: Miranshah, North Waziristan, Forensic Architecture March 30, 2012.

The research team’s main focus is the “spatial” element of drone strikes, meaning the urban and architectural component of bombing campaigns.70 This meant compiling and visualizing data regarding the patterns and number of casualties, the location of strikes within village settings, and the buildings typically the targets of lethal strikes. Members of Forensic Architecture explain the digital reconstruction of an attack that took place in the Miranshah territory of North Waziristan in 2012: “[t]he missile is designed to penetrate through a ceiling, and detonate when inside a room, spraying hundreds of steel fragments and killing everybody in proximity.” Subsequently, “[e]ach fragment was studied and mapped. Where the distribution of fragments is in lower density, it is likely that something absorbed them. Although we could not be certain, it is possible that the absence of the fragments indicated the places where people died.” Just so, we revisit the fifteenth-century meaning of redaction: namely, to “redacte into duste,” a material thing reduced, pulverized, or incinerated.

How might a cultural poetics expand to embody a comparable form of militant research? For Mark Nowak, documentary poetics is not so much a movement as a “modality within poetry” that one might plot “along a continuum from the first person auto-ethnographic mode of inscription to a more objective third person documentarian tendency (with practitioners located at points all across that continuum).”71 Along this ethnographic spectrum, autobiography, biography, and reportage find their place in a poetics of testimony, witness, and investigation, variously named. The author of Coal Mountain Elementary (2009) rightly points to doc/po’s resiliency as a mixed-media form that blends the cinematic, photographic, literary, and the auditory/performative. Add to this a variety of non-traditional artistic forms – charts, diagrams, maps, and other forms of “visual knowledge production” (Johanna Drucker’s term).72 Writing with Dee Morris for Jacket2 Magazine, we argue that books like Metres’s Sand Opera, Caroline Bergvall’s Drift (2014), M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! (2011), Rachel Zolf’s Neighbor Procedure (2010), and Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Ode (2014) develop an “evidence-collecting and case-making poetry, poetry that combines aesthetic and political practices in search of public truth and moral accountability.”73 We might productively expand Nowak’s ethnographic model of poetic inquiry to include a counter–forensic poetics of militant research, one that reverse-engineers those technologies of surveillance and warfare increasingly absorbed into the fabric of everyday life.

In the twenty-first century, redaction has become more than just a technique of censorship chiefly associated with the bureaucratic administration of empire. It has developed its own symbolic logic, closely related to the “everywhere-anytime war,” each pitch-dark line a miniature black site within the media history of records.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi, Guantánamo Diaries, ed. Larry Siems (New York: Little, Brown, and Co., 2015), 234-35. ↩

Philip Metres, Sand Opera (Farmington, ME: Alice James Books), 8. ↩

Craig Dworkin, Reading the Illegible (Evanston: Northwestern UP, 2003), xviii. ↩

The “Dark Prison” is also known by its military codenames the Salt Pit and Cobalt. See Human Rights Watch, “U.S. Operated Secret ‘Dark Prison’ in Kabul.” Writing for The New York Times, David Johnston and Mark Mazetti cite CIA officials who claim “Strawberry Fields” is a reference to the Beatles’ song “Strawberry Fields Forever,” referring to the indefinite term prisoners are held at the camp. See “Interrogation Inc.: A Window into Into CIA’s Embrace of Secret Jails.” ↩

Slahi, Guantánamo Diaries, 359 ↩

Slahi, Guantánamo Diaries, 359-61. ↩

See Judith Butler’s analysis of this collection in Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (New York: Verso, 2009), 55-62. ↩

Slahi, Guantánamo Diaries, xi. ↩

Quoted in Cora Currier, “How Guantánamo Diary Escaped the Black Hole and Got Past the Censors (Mostly),” The Intercept, 31 Jan. 2015. Italics mine. ↩

Mark Danner, “No Exit,” The New York Times Book Review, 1 Feb. 2015, 18. ↩

One should be careful, here, not to conflate several distinct and potentially antithetical notions of blackness. Fred Moten instructs us: “Black ops. Black Sites. What is it that now one has to forge a paleonymic (r)elation to black, to blackness? The word persists, now, under erasure or eclipse, ceded to the state of law/exception. The word is begrudged, grungy, dingy, encased in a low tinge, always understood as being in need of a highlight.” Hence, other meanings of blackness might intercede and challenge this semantic frame. Moten’s claim appears in his unpublished essay, “Black Optimism/Black Operation,” <https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/…/files/…/moten-black-optimism.doc>, 2007, 5. See also, “Black Op.” PMLA 123(5): 1743-7, and “The Case for Blackness,” Criticism 50.2 (Spring 2008): 177-218. ↩

Eyal Weizman: “We were on the other hand committed to the possibilities of reversing the forensic gaze, to ways of turning forensics into a counter-hegemonic practice able to invert the relation between individuals and states, to challenge and resist state and corporate violence and the tyranny of their truth. Transformative politics must begin with material issues, just as the revolutionary vortex slowly gathered pace around the maggots in the rotten meat on board the Potemkin.” See Weizman, “Introduction,” Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth (London: Sternberg Press and Forensic Architecture, 2014), 11. ↩

OED adj. 3b, v. 3b. ↩

Marcel Broodthaers, “Poesie – unique source” (Poetry – unique source Part A, lc of L’exposition à la Galerie, in Jeu de Paume, in Deborah Schultz, Marcel Broodthaers: Strategy and Dialogue (Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang, 2007), 37. ↩

Craig Dworkin, Reading the Illegible, 150. ↩

Bob Brown, Gems: A Censored Anthology, 1930, Ed. Craig Saper (New York: Roving Eye Press, 2014), 17. ↩

Brown, Gems, 58. ↩

See Paul S. Boyer, Purity in Print: Book Censorship in America from The Gilded Age to the Computer Age, 2nd ed. (Madison, WI: U of Wisconsin P, 2002). ↩

Boyer, Purity in Print, ix. ↩

Annabel Patterson, Censorship and Interpretation: The Conditions of Writing and Reading in Early Modern England (Madison, WI: U of Wisconsin P, 1991), 11. Patterson elaborates, “a theory of functional ambiguity, in which the indeterminacy inveterate to language was fully and knowingly exploited by authors and readers alike (and among those readers, of course, were those who were most interested in control),” 18. ↩

Judith Butler in Frames of War: “I refer to ‘representability’ here, rather than ‘representation,’ because this field is structured by state permission (or, rather, the state seeks to establish control over it, if always with only partial success). As a result, we cannot understand the field of representability simply by examining its explicit contents, since it is constituted fundamentally by what is left out, maintained outside the frame within which representations appear. We can think of the frame, then, as active, as both jettisoning and presenting, and as doing both at once.” Butler continues, “that such a form of power is non-figurable as an intentional subject does not mean that it cannot be marked or shown. On the contrary, what is shown when it comes into view is the staging apparatus itself, the maps that exclude certain regions, the directives of the army, the positioning of the cameras, the punishments that lie in wait if reporting protocols are breached.” See Frames of War, 73-4. ↩

Lisa Gitelman, Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents, Sign, Storage, Transmission (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2014), 87. See also, Cornelia Vismann, Files: Law and Media Technology, Trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, Meridian: Crossing Aesthetics (Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2008; Alan Delgado, The Enormous File: A Social History of the Office (London: John Murray, 1979). ↩

For a deft assessment of the Pentagon Papers’ multiple editions, see H. Bradford Westerfield, “What Use Are Three Versions of the Pentagon Papers?” American Political Science Review 69.2 (1975), 685-9. ↩

Gitelman, Paper Knowledge, 88-9. ↩

See Thomas S. Blanton, “Veto Battle 30 Years Ago Set Freedom of Information Norms: Scalia, Rumsfeld, Cheney Opposed Open Government Bill,” Electronic Briefing Book No. 142, National Security Archive, 23 Nov. 2004. ↩

For an excellent overview of the FOIA, see Athan G. Theoharis, ed., A Culture of Secrecy: The Government Versus the People’s Right to Know (Lawrence, KS: UP of Kansas, 1998). Literary scholars should consult William J. Maxwell, F.B. Eyes: How J. Edgar Hoover’s Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2015) and his F.B. Eyes Digital Archive. ↩

See Ted Bridis, “Obama Administration Sets New Record Withholding FOIA Requests,” PBS News Hour, 18 Mar. 2015; Gary Pruitt, “AP CEO: Government Undermining ‘Right to Know’ Laws,” Associated Press, 13 Mar. 2015. ↩

Julia Meltzer and David Thorne, It’s not my memory of it: three recollected documents, The Speculative Archive for Historical Clarification, video installation, 2003. The film is distributed by Video Data Bank and V-Tape. ↩

Robert Storr, “Paper Trail” in Redaction Paintings, Jenny Holzer Archive (New York: Cheim and Read, 2006), 8. See also, Robert Bailey, “Unknown Knowns: Jenny Holzer’s Redaction Paintings and the History of the War on Terror,” OCTOBER 142 (Fall 2012), 144-61. ↩

See the National Security Archive, U.S. Central Command Slide Compilation, ca. August 15, 2002. ↩

The term “theater of war” first appeared in Carl von Clausewitz’s On War (1832), written largely in the wake of the Napoleonic wars. For useful readings of Clausewitz, see Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1987), p. 419 ff. See also, Michel Foucault, Lectures 1, 3, and 7 of “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-1976, eds. Mauro Bertani and Alessandro Fontana, trans. David Macey (New York: Picador, 2003). ↩

Hart Seely, “The Poetry of D.J. Rumsfield,” Slate Apr. 2003. Seely’s satiric verse was later published in Pieces of Intelligence: The Existential Poetry of Donald H. Rumsfeld (New York: Free Press, 2009). ↩

Mariam Ghani, The Trespassers, 2011. ↩

Ghani, The Trespassers, 2011. ↩

Metres, “When I Was a Child, I Lived as a Child, I Said to My Dad,” Sand Opera, 62. ↩

Metres, Sand Opera, 62. ↩

Saskia Sassan, “When the City Itself Becomes a Technology of War,” Theory, Culture & Society, 27.6 (2010), 37; Derek Gregory, “The Everywhere War,” The Geographical Journal 177.3 (Sept. 2011), 238; Jeremy Scahill, Dirty Wars: The World is a Battlefield (New York: Nation Books, 2014); Samir Amin, The Liberal Virus: Permanent War and the Americanization of the World (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2004); Mark Duffield, Development, Security and Unending War: Governing the World of Peoples (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2007); and Dexter Filkins, The Forever War (New York: Vintage, 2009). Note also the shift in Paul Virilio’s thought a quarter century after the publication of Pure War (1983). Paul Virilio, “Introduction: Impure War,” Virilio and Sylvère Lotringer, Pure War: Twenty Five Years Later, trans. Mark Polizzotti (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2008), 7-13. ↩

Nick Turse, “The Special Ops Surge: America’s War in 134 Countries,” TomDispatch.com, 16 Jan. 2014. ↩

William Hartung, “Military Strategy? Who Needs It?: The Madness of Funding the Pentagon to Cover the Globe,” TomDispatch.com, 26 Mar. 2015. ↩

For expanded discussions of drone warfare, see Medea Benjamin, Drone Warfare: Killing By Remote Control (New York: Verso, 2013); Derek Gregory, From a View to a Kill: Drones and Late Modern War,” Theory, Culture, & Society 28.7-8 (2011): 188-215; “Nick Turse and Tom Engelhardt, Terminator Planet: The First History of Drone Warfare, 2001-2050 (CreateSpace Independent Pub. Platform, 2012); Akbar Ahmed, The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam (India: HarperCollins, 2013); P.W. Singer, Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century (New York: Penguin Books, 2009); and Grégoire Chamayou, A Theory of the Drone (New York: The New P, 2015). See also, the joint study conducted by the International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic at Stanford Law School and the Global Justice Clinic at New York University School of Law, Living Under Drones: Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan, 2012, http://chrgj.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Living-Under-Drones.pdf. See also Garrett Stewart’s chapter “Digital Reconnaissance and Wired War” from his study of contemporary film, Closed Circuits: Screening Narrative Surveillance (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2015). With deft readings of films such as Home of the Brave, The Green Zone, Redacted, and Battle for Haditha, Stewart remarks: “There are few panoramic scenes in these narratives of the last decade, no martial choreography, no geometric symmetries of spectacle, few wide-screen needs – or satisfactions – whatsoever. Battle, usually renamed ‘firefight’ – a function more of ad-hoc counterinsurgency than grand design – has fragmented into the extreme contingencies of sniping and roadside bomb blasts. War is so total that it is nowhere and everywhere at once. So that what the War on Terror film serves to picture is for the most part a soldiery without a genre …. Although the philosopher Paul Virilio has repeatedly linked cinema at large to a battlefield’s ‘logistics of perception,’ these new films – with their depleted plots of intermittent skirmishes, roadside sabotage by improvised explosive devices (IEDs), recurrent panic, mayhem, and localized reprisal – have lost almost all narrative (as well as martial) logic while surrendering perception to the flash of image and its random capture” (170). ↩

James Fallows, “The Tragedy of the American Military,” The Atlantic 315.1 (Jan./Feb. 2015), 74-5. ↩

Washington Post, “Black Budget,” 29 Aug. 2013. The data visualization is based on the “FY 2013 Congressional Budget Justification (vol. 1: National Intelligence Program Summary)” provided by whistle blower Edward Snowden. ↩

For an excellent account of the Stuxnet program, see Kim Zetter, Countdown to Zero Day: Stuxnet and the Launch of the World’s First Digital Weapon, New York: Crown Pub. Group, 2014. For an abbreviated assessment, see Zetter’s article in Wired: “An Unprecedented Look at Stuxnet, The World’s First Digital Weapon,” Wired Magazine, Online Ed., 3 Nov. 2014. ↩

Washington Post, “Black Budget,” 29 Aug. 2013. ↩

Trevor Paglen, Blank Spots on the Map: The Dark Geography of the Pentagon’s Secret World (New York: Dutton, 2009), 205. ↩

For an overview of the role played by private contractors since the beginning of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, including security, intelligence, and interrogation, see Tim Shorrock, Spies for Hire: The Secret World of Intelligence Outsourcing (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009); Jeremy Scahill, Black Water: The Rise of the World’s Most Powerful Mercenary Army (New York: Nation Books, 2008); and Robert Young Pelton, Licensed to Kill: Privatizing the War on Terror (New York: Broadway Books, 2006). ↩

Paglen, Blank Spots on the Map, 169-70. ↩

Paglen, Blank Spots on the Map, 173. ↩

Paglen, Blank Spots on the Map, 175. ↩

Trevor Paglen, “New Photos of the NSA and Other Top Intelligence Agencies Revealed for First Time.” The Intercept and Creative Time Reports. 9 Feb. 2014. ↩

See Judith Richards, Robert Hobbs, and Mark Lombardi, Mark Lombardi: Global Networks (New York: Independent Curators International, 2003); Laura Kurgan, projects at Spatial Information Design Lab; Josh On, They Rule. ↩

Trevor Paglen, The Black Sites, TrevorPaglen.com, 2006. ↩

Metres: “I suppose it’s possible also to read the title ironically, since placing ‘sand’ next to ‘opera’ is to juxtapose the low and the high, the natural and the artificial, etc. “Sand,” of course, is also a silly Orientalist stereotype about the Middle East, whose geography and ecosystems are quite varied.” See Alice James Books, “An Interview with Philip Metres,” Alice James Books Newsletter, 19.2 (Fall 2014), 7. ↩

See the Combat Paper Project. ↩

“At the Borders of our Tongue: Fady Joudah Interviews Philip Metres,” Los Angeles Review of Books, 23 Feb. 2015. ↩

Metres, Sand Opera, 7. ↩

Philip Metres, “(echo /ex/),” Sand Opera, 8. ↩

Metres, Sand Opera, 8. ↩

Alice James Books, “An Interview with Philip Metres,” 6. ↩

See Mohamed Bashmilah profile, The Rendition Project: Researching the ——– Globalization of Rendition and Secret Detention, here; also see the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, “Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program: Executive Summary” (“Torture Report”); for an instructive assessment of the SSDI’s heavily redacted executive summary, see Dan Froomkin, “12 Things to Keep in Mind When You Read the Torture Report,” The Intercept, 2 Dec. 2014. ↩

Metres, Sand Opera, 71-3, 81. ↩

See the Hoffman Report (“Report to the Special Committee of The Board of Directors of the American Psychological Association: Independent Review Relating to APA Ethics Guidelines, National Security Interrogations, and Torture,” 2 Jul. 2015, here. Also see James Risen’s work, Pay Any Price: Greed, Power, and Endless War (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014). ↩

Jordan Scott (with audio composed by Jason Starnes), Clearance Process, Small Caps Series (Vancouver: The Capilano Review, 2016), 7, 11. ↩

Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2003), 41. ↩

Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1997), 3. Note an important distinction: unlike Sontag, Hartman reserves no special place for literature to represent more efficaciously the ethics of suffering. ↩

Butler, Frames of War, 74. ↩

Moten, “The Case for Blackness,” Criticism 50.2 (Spring 2008): 177-218. 179. ↩

The SRCT Interim Report was presented to the United Nations General Assembly in New York on October 25, 2013. ↩

Forensic Architecture, “Drone Strikes: Investigating Covert Operations Through Spatial Media,” Centre for Research Architecture, in the Department of Visual Cultures, Goldsmiths, University of London, ca. 2011. ↩

Mark Nowak, “Documentary Poetics,” Harriet Blog, The Poetry Foundation, 17 Apr. 2010. ↩

Johanna Drucker, Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production, MetaLABprojects (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014). ↩

Dee Morris and Stephen Voyce, “Forensic Mapping,” Jacket2 Magazine, 23 Apr. 2015. ↩

This article is dedicated to Mohamedou Ould Slahi.

I would like to express my gratitude to Dee Morris. Our co-written commentaries for Jacket2 laid the groundwork for this essay. Thanks as well to Angela Rawlings, Jordan Scott, Michael Nardone, and Nick Thurston, for their invaluable editorial comment.

Article: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Image: Kristen Mueller, "Sleep, Night," from Partially Removing the Remove of Literature, 2014.