The poetry reading in Canada developed into an increasingly important form of literary expression in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s alongside the development of literary publishing in Canada, the teaching of Canadian literature in university English departments, and the establishment of the Canada Council for the Arts. Poetry readings gained a foothold in the literary imagination of cultural agents in Canada with a scope and intensity akin to the explosion of little magazines and small presses in these same decades. This occurred, in part, due to the relationship of poetry readings, as a specific form of cultural production, to the nationalist interventions of the Canada Council. Yet this relationship was a fraught one, not unlike the relationships writers and publishing houses had with the Canada Council. Jason Camlot and Darren Wershler, in their working paper “Theses on Discerning the Reading Series,”1 call for approaches to studying poetry readings predicated on “an historical understanding of the place of different reading practices in relation to historical conceptions of the literary.”2 The emergence of the Canada Council framed conceptions of the “literary” in liberating and restricting ways in these decades, codifying various literary categories based on the eligibility requirements of evolving categories of funding (malleable and responsive at first, ordered and constricting in later years). The myriad forces that nurtured the aesthetic development of Canada’s literary fields in the decades following the Second World War have been documented and studied by critics for years now, with complex networks of national and international influence traced and contested.3 The intervention of the Canada Council was germane to these networks on a material level. Council funding provided the literal means necessary for many of Canada’s cultural agents to pursue their projects (I use “agents” here, and throughout the paper, in relation to Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of the field of cultural production in order to encompass writers as well as editors, publishers, event-organizers, critics, and other actors within the field).

The Canada Council for the Arts is a Canadian Crown Corporation founded in 1957. It supports and promotes the production of Canadian art in a variety of fields (visual arts, media arts, dance, music, theatre, writing, and publishing) through funding to artists and arts organizations. It was created based on the recommendations of the Massey Commission Report of the Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences 1949–1951 (1951), a foundational document in the forging of the nationalist links between the Canadian Government and the production of art in Canada. The Massey Report was commissioned by the Government of Canada based on the belief that it was “desirable that the Canadian people should know as much as possible about their country, its history and traditions; and about their national life and common achievements.”4 The Government felt it was “in the national interest to give encouragement to institutions which express national feeling, promote common understanding and add to the variety and richness of Canadian life.”5 Among numerous recommendations, the Report proposed establishing the Canada Council as well as founding a National Library (something Canada did not have until 1953, and a direct result of the Report’s recommendation).

Since 1957, the Canada Council has acquired a central place in supporting the production, dissemination, and reception of Canadian art, both by funding artists directly and through the development of structures that distribute and preserve work. It was not (and still is not) without critics of the tension between centralized government support and marginal, ostensibly oppositional artistic practice (tensions that will be discussed in greater detail shortly), but it nonetheless provided (and provides) material financial support necessary to the current state of Canadian arts and letters. Ken Norris, in his study of the rise of the little magazine in Canada, cites the financial aid provided by the Canada Council as a vital new resource that enabled the rapid proliferation of magazines across the country.6 Karl Siegler, editor of Vancouver-based small press Talonbooks from 1974–2007, makes a similar yet conflicted case for the interventions of the Council from the mid–1960s on: “In the intervening thirty years, we did, in fact, create a vibrant, post-colonial Canadian literature and culture of our own […]. And how did we do that? The way all struggles of liberation, the re-inscription of the self and the other, are carried out. Through sweat equity, and a great deal of help from our colonial government.”7 The “colonial” help provided by the Government of Canada for Canadian literature was distributed to writers, as well as to publishers of small presses and little magazines. Organizers of poetry readings received tenuous funding beginning in 1959, support that cultural agents fought to stabilize during the ensuing decade before it became firmly established in the offices of the Council by 1970.

At a structural level, the funding of poetry readings by the Canada Council supplies an opportunity to engage with the active processes of the formation of cultural policy, or, to borrow Camlot and Wershler’s terms, to investigate literary readings as “[instruments] of cultural policy that [position] subjects in relationship to the State and its official and unofficial cultures.”8 According to Pierre Bourdieu, the “fundamental stake in literary struggles is the monopoly of literary legitimacy, i.e., inter alia, the monopoly of the power to say with authority who are authorized to call themselves writers; or, to put it another way, it is the monopoly of the power to consecrate producers or products.”9 The Canada Council rapidly became the primary national body wielding the power to define literary legitimacy by way of grants and prizes. However, as Barbara Godard notes, this degree of government financial support compromises the presumed autonomy of Bourdieu’s fields.10 Pauline Butling traces the complexity of the manner in which literary production related to Council funding and its “centripetal, homogenizing narratives of the nation”:

Obviously the prizes, public reading programs, writers-in-residence programs, and grants to publishers, magazines, and individuals have provided invaluable financial support for both communities and individuals. Less obvious are the benefits derived from Canada’s peculiar combination of nationalism and modernism. To prove to the world that the nation has shed its colonial past and achieved mature nation status (a nationalist goal), the government supports experimental, “avant-garde” art (a modernist goal). The Canada Council has thus regularly supported innovative, experimental, separatist, independent, even anarchic work as much as mainstream cultural production.11

Canada Council support was not universally adopted by cultural agents in the fields of Canadian literature. Butling points to the magazines NMFG (No Money From the Government) and filling Station [sic], as well as the 1980s small press scene in Toronto, as examples of independent Marxist positions relative to Council grants.12 Oppositional positions of this sort are rooted in resistance to the “market-oriented, corporate ideology”13 that forms the basis of the rules of applying for and receiving funding. Frank Davey’s critical examination of the material-economic specifics of Council funding dissects the influence of the “block-grant” program, including its role in defining what constitutes a book. To qualify, books must be a minimum of 48-pages, placing funding out-of-reach for shorter titles and “privileging […] the 100–200 page novel as the standard of English-Canadian publishers,”14 thus directly influencing what is and is not published in Canada. Other critics confront problems of jury bias, wherein “the so-called ‘peer’ juries were, for many years, almost exclusively composed of mainstream subjects”,15 consigning marginal subjects to more difficult struggles to acquire support.

The relationship of literary readings to the Canada Council is a productive, yet largely unexplored, component of this body of forces. Darren Wershler, following from Barbara Godard’s charge to include the critical study of cultural policy within literary studies, signals one way that the study of literary readings can both illuminate and be illuminated by critical engagement with cultural policy: “[Godard gestures] toward an equal but opposite imperative – the need to look outside the text at the assemblages of discourse, power, material media forms and systems of circulation that allow particular statements to come into being at a particular time and place, and imbue them with significance.”16 Literary readings are particularly suited to this practice because they already exist fundamentally “outside” the text as it is typically conceived and studied. The emphasis of a public reading does not fall on the printed page, but rather on public utterance. Literary readings were anomalous in Canada in the 1950s, staging an alternative material manifestation of literature, circulating human bodies as opposed to printed texts. The novelty of public readings rendered them open to experiment. As the model for funding readings developed throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, structures became fixed, widely adopted, and normalized, due in large part to the availability of funding and the necessity to apply for such funding in regulated patterns. In our current critical moment, poetry readings furnish the opportunity to study literary production, dissemination, and communities in novel ways due to this characteristic of being “outside” the text. Wershler calls for scholarship that treats art “not as a conduit, but as a kind of critique at the limits of what cultural policy (critical and uncritical alike) will currently allow itself to think.”17 As literary readings did not exist as a category at the offices of the Canada Council in 1957, they therefore performed this function. An attentive examination of the funding of readings in these years will reveal cultural policy in the act of “allowing itself to think” in slightly wider terms. In the activities of the Canada Council and the poets who lobbied for funding, we can observe an alternative model of cultural funding that was initially adaptable and responsive to the needs of cultural agents.

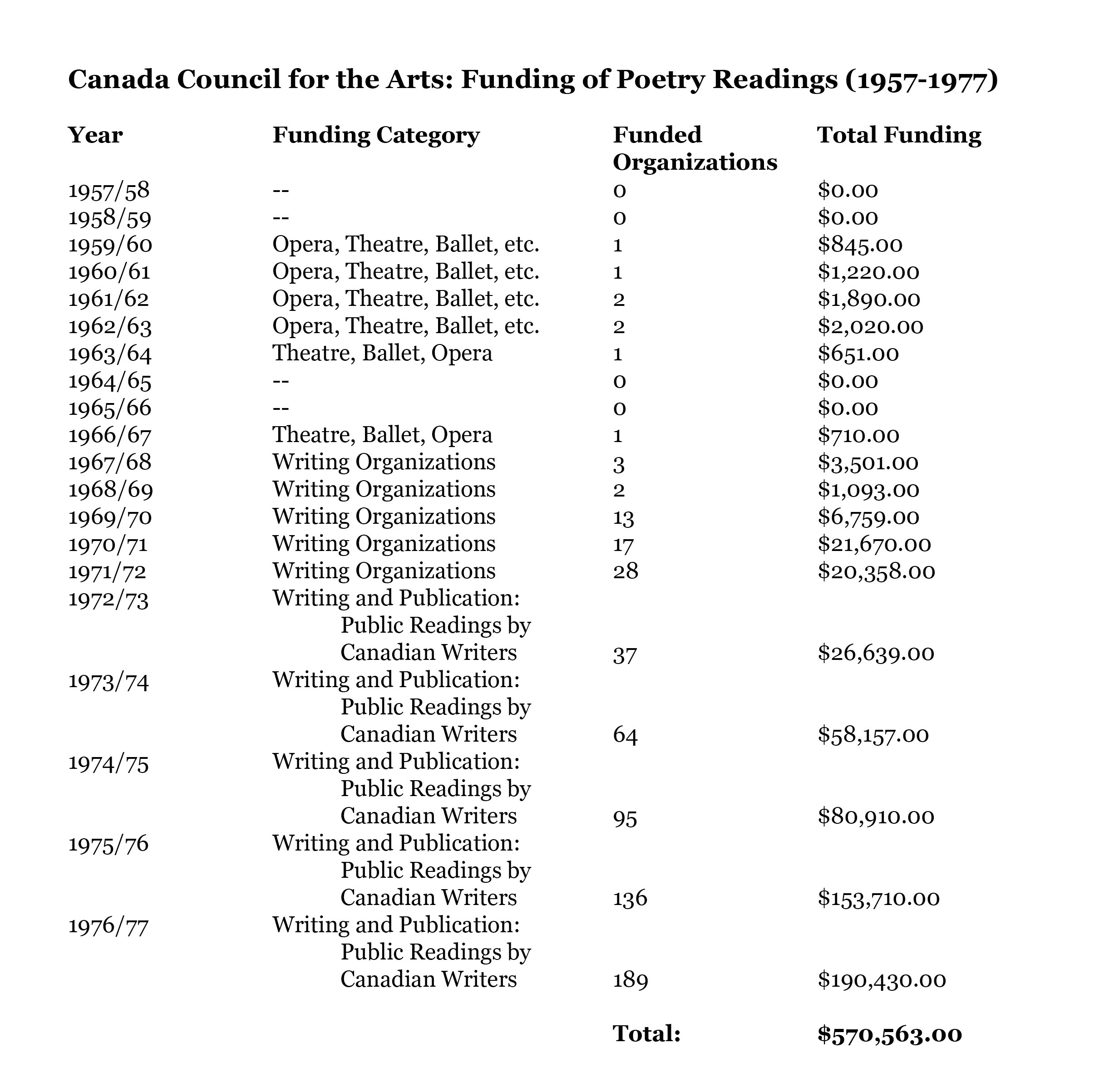

The table below organizes information gathered from the Council’s published Annual Reports to illustrate the staggering rate of growth in both the number of literary readings (and organizations) and the funding made available by the Council during the first two decades of its operation. This table does not, and cannot, reflect the complete network of poetry readings and organizations that flourished during these decades. The emphasis of this table follows from the emphasis of this paper on the role of the Canada Council in funding a particular type of poetry reading. Unaccounted for here are series that submitted failed applications, series that missed deadlines, series that were unaware of the availability of such funding, as well as series that were not interested in applying for funding (whether because it was not required or because of a politically motivated opposition to the Canada Council).

In 1959, the Council funded a poetry reading series for the first time. The Contact Poetry Readings received $845.00 to “provide travel and assistance to Canadian poets to present readings of their own work at the Isaacs Gallery, Toronto.”18 The Contact Poetry Readings ran from 1957–1962. Raymond Souster was the primary force behind the series, but was aided by others, including Kenneth McRobbie, John Robert Colombo, Peter Miller, and Avrom Isaacs. Initially, organizers drew on poets in Montreal and Toronto due to financial limitations. However, Canada Council grants received in 1959,1960 and 1961 enabled the series to present a list of emerging and established poets from across Canada and the United States.19 The Contact Readings established a creatively successful Canadian precedent for poetry reading series, while simultaneously drawing Canadian poetry into a broader international dialogue with similarly focused modernist and early postmodernist communities.

The Council’s tentative decision to fund readings plays out in a series of letters between Kenneth McRobbie, on behalf of the Contact Readings, and Dr. A.W. Trueman, Director of the Canada Council, written between May and July 1959. This correspondence is fascinating for how it reveals McRobbie’s evident anxiety and frustration. Trueman, for his part, is sceptical, but ultimately willing. McRobbie first contacts the Council on May 20, 1959, via a secretary. He inquires as to how an arts organization should apply for a grant, knowing there is no precedent at the Canada Council for funding poetry readings. McRobbie emphasizes what he perceives to be the value of such events:

This project can provide a valuable service to letters in Canada. It will help reimburse (to a minute extent) poets who incur many expenses over the years for the satisfaction of putting their work before the public…it can help restore the spoken word to poetry, in the sphere of entertainment. It will enable the public to see that poets are human after all, and create an interest in literary activity. And these readings will do much to offset the sheer geographical handicap for poets of being scattered in all parts of Canada, for too few of them have personal contact with other writers in other parts of the country.20

McRobbie receives a quick rejection before trying again on May 30, this time contacting Trueman directly. His frustration is palpable: “I stressed that I was not applying for a Scholarship for an individual. Yet Mr. Noonan sends me a stock refusal on the grounds that my application does not ask for what I had no intention of asking for in the first place.”21 McRobbie continues:

I know very well that you make grants to groups—as well as to individuals. I know that you assisted drama groups, small orchestras, a variety of other endeavours in no way more deserving than those whose interests I have at heart. I know also that several times I have read pronouncements by your committee that you are looking for projects which have already proved their worth in practical operation.

At this stage, the Canada Council begins to act in ways that are sensitive and responsive to the specific needs and goals of the Contact Poetry Readings, revealing a template for cultural funding and cultural policy that was able to evolve in the Council’s early days due to the relatively small scale of its operation. Poetry readings were not yet visible to the Canada Council in 1957 when it was founded; it had no category under which to fund such events. Nevertheless, and to the Council’s credit, it endeavoured to find a way to support the fledgling Toronto series.

Trueman passed the application along to Peter Dwyer, Arts Supervisor at the Council. There was concern about the scale of the readings. Dwyer worries that “the average size of the audience was 55 and […] this seems to be a very limited outlet.”22 During the process of evaluation, the Council expresses concern about whether they can justify spending money to “[provide] personal enjoyment for a very small group of people who like to hear poetry readings.”23 Despite these anxieties, the Canada Council decided to fund them, describing the act as an “experiment”24 in its Third Annual Report. Dwyer writes to Kenneth McRobbie on September 1, 1959 with the verdict:

The Council agreed to set aside a sum of $845 [of a requested $1,312.00] representing the sum of the amounts set out in your estimate for reading fees ($275), expenses per day ($180) and travel expenses ($390)…the Council has been impressed by what it has been told of the value of readings of this kind to the poets themselves.25

Poets were given a $25.00 reading fee, as well as contributions to travel and accommodations. The novelty of this grant is made plain by the fact of it having been given under the category “Opera, Theatre, Ballet, etc.,” alongside grants made to the Canadian Opera Company and the National Ballet Guild of Canada. The size of the readings, while a partial concern initially, was also likely an encouragement to the Council to fund the series as the grant was a relatively small investment compared to others that were being granted in the same category. For example, the $845.00 given to the Contact Readings constitutes less than 1% of the $100,000.00 given to the National Ballet Guild.

The series and the grant were so novel that the Council felt it worthwhile to include several paragraphs about the organization in their Annual Report. The Council wrote:

There should be nothing unusual in the reading of poetry aloud. Indeed in its origins it was most likely intended to be sung or recited. But poetry readings have not been common in Canada, and therefore the assistance which the Council has recently given for this purpose was something of an experiment.26

Underscoring the novelty of the series in the Canadian landscape, the Council also emphasizes how many of the Contact Readings poets were giving their first public reading in Canada (among these were Al Purdy, Ralph Gustafson, and A.J.M. Smith). Though it is difficult to believe that A.J.M. Smith had not read in Canada prior to 1959, that the organizers (and in some cases the poets) made such claims suggests that readings were, at the very least, scattered and infrequent. The report quotes from an unidentified poet who describes the benefit of the experience in personal terms:

It strengthened my sense of contact. And I think this is of vast importance, creatively. And it is certainly of special importance to a writer like myself, living in an isolated part of the country cut off from direct communication with other writers or even with people who are interested in poetry from the audience standpoint. Throughout my youth I had to fight the thought that I was, perhaps, the only person in the world who was interested in the least in poetry…The brief visit to Toronto helped offset that isolation, and thus helped me creatively.27

The Contact Readings received further grants of $1220.00 in 1960/61 and $1290.00 in 1961/62.

Frank Milligan, long-time administrator at the Canada Council, argues that this type of thoughtful, responsive approach to cultural funding in the first years of the Council’s existence can be traced to views that were implicit in its founding principles:

This approach, which sees government and the political processes as a much more untidy affair, rejects the attribution of goals to an abstraction, “the nation” – with all its accompanying overtones of Rousseau’s General Will. It insists instead on the reality of twenty-odd million citizens, each with his own cluster of goals, divergent and contradictory not only among the citizens but within each cluster as well. The task of government then, is not to eliminate contradiction and ambiguities in the name of some mythical higher goals, but to accommodate and reflect, in its actions, all the contending wants of the public in a way that yields as equitable as possible a balance of satisfaction – at least of dissatisfaction.28

Milligan describes this approach as “highly imperfect”29 but suggests it is the best available option. His emphasis on the “reality” of “divergent and contradictory goals” is the type of unwieldy, experimental approach that could only be practiced at a time when the Canada Council was brand new and operating with a staff of only nineteen30 and at a time before Canada Council funding had become vital to the establishment and survival of a majority of mid- and large-scale literary activities in the nation. Peter Dwyer and A.W. Trueman were able to “accommodate and reflect” Kenneth McRobbie’s request in their funding model because the model was still fundamentally malleable. Robert Fulford, profiling the Canada Council in 1982 on the occasion of its twenty-fifth anniversary, argues that the early years were a learning process for everyone involved: “The council people – including the first director, Albert Trueman – saw this as a time to learn their jobs, develop as an institution, and make no noise.”31 Moreover, it appears that the bureaucrats tasked with making such decisions had personal affinities for the goals of writers and organizers of literary events. Peter Dwyer, who worked for the Council from 1958 until his death in 1972 as Assistant Director, Associate Director, and finally Director, is a prime example. Dwyer, a former liaison officer in the British Secret Intelligence Service, was active in theatrical productions throughout his education and sat on the Board of Directors of the Ottawa Little Theatre. Dwyer also wrote a one-act play, Hoodman-Blind, which co-won first prize in the Ottawa Little Theatre’s national playwriting competition in 1953.32

One further feature of the experimental nature of the Council’s funding of the Contact Readings is the manner in which the Council funded American readers. Although the accompanying note for the grant made to the Contact Readings in 1959 stated that the money was intended to “provide travel and assistance to Canadian poets [emphasis added],”33 American poets were also funded by this grant. Denise Levertov and Charles Olson received money from the Canada Council for their trips to Toronto to read in the series in 1959/1960. In 1960/61, Leroi Jones, Louis Zukofsky, Cid Corman and Theodore Enslin were funded. In 1961/62, Robert Creeley, Frank O’Hara, and Charles Olson received funding to read in Toronto. By this final season, the funding of American poets was beginning to be questioned. Trueman, in his internal report, remarks, “I am not sure whether the Council will wish to continue grants to bring in poets from the U.S. We are told that their presence is stimulating.”34 The willingness of the Council to fund American readers based on being told that “their presence [was] stimulating” is striking given the anti-American anxiety that permeates discussion of the mandate of the Council and the document that led directly to its creation, The Report on the Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences (1951). Paul Litt argues that the Massey Commission “in its final report…would single out the influence of the US as the greatest threat to the development of a distinct Canadian culture.”35 Dilys Hankins, tracing the relationship between the Council and the establishment of a National Theatre, argues that in “the Commission’s view, Canadian self-expression was being adversely influenced by American values, ideas, and thoughts as American cultural ‘output’ was felt through most areas of Canadian life.”36

These attitudes can be located in certain places in The Massey Commission. For example, under the heading “The Future of Canadian Letters,” the report states

we do think it important to comment on the efforts of those literary groups belonging to various schools of thought which strive to defend Canadian literature against the deluge of less worthy American publications. These, we are told, threaten our national values, corrupt our literary taste and endanger the livelihood of our writers.37

However, there is another thread that can be traced in the findings of the report that argues in favour of the necessity of engaging Canadian cultural life with international influences. The report states, “the literature of the United States, which in the last thirty years has acquired an increasing international reputation, exercises an impact which is beneficial in many respects no doubt, but which, at the same time, may be almost overpowering.”38 Moreover, in its official recommendation that “a body be created known as the Canada Council,”39 the report emphasizes that one role of this new body will be to “foster Canada’s cultural relations abroad.”40 While the Council in many respects was established as, and continues to exist as, the “centripetal, homogenizing” force described by Pauline Butling, an alternative was always present in its foundational structures.

Robert Lecker identifies the mandate of the Council as a “federalist and culturally elitist ideology”41 directed toward the goal of “stabilizing nationhood”42 that nonetheless “embraced the new, the innovative, the unconventional, and the regional”43 despite the implicit subversive challenges these activities posed to the ideal of a coherent national identity. Lecker argues that supporting such activities “was intended to demonstrate that federalism could encompass – and still does encompass – difference.”44 Such broad terms, however, obscure the actions of individuals engaged in the Council’s day-to-day decision making, especially in its earliest days, before procedures had been developed, let alone become fixed and routine. Without question, Peter Dwyer, A.W. Trueman, and other early administrators operated within a federalist mandate, but one that did not restrict their ability to fund experimental work they believed was deserving of financial support, however minimal. Dwyer engaged directly with poets and audience members, soliciting opinions on the value of such activities (including the funding of American readers) before deciding that the Council should “experiment” by funding them.

Despite the initial grant to the Contact Readings in 1959, funding of poetry readings proceeded irregularly for several years. 1962 is notable for marking the first time that the Council funded two different sets of readings, the second at Le Hibou in Ottawa. In 1962/63 organizations in Edmonton and Vancouver received funding. The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts received funding for poetry readings in 1963/64. The following two years saw no organizations receive funding (it is unclear whether this was due to lack of applications or to the quality of applications received). The Poetry Series at Sir George Williams appears in the Canada Council Annual Reports for the first time in 1966/1967, and received the only grant given out that year. Readings continued to be funded under “Opera, Theatre, Ballet, etc.” (renamed “Theatre, Ballet, Opera” in 1963/64) until 1967/68. At this point, funding for poetry readings was subsumed under the general body of grants made to “Writing Organizations.” In 1972/73, a new funding category was created to manage the rapid rise in grants that the Council was making to poetry readings across the country: “Public Readings by Canadian Writers.” The emphasis of this new category falls clearly on “Canadian,” clarifying and restricting how federal arts funding could be spent.

Among the most interesting recorded comments from the Canada Council regarding its first ever grant to a poetry reading series was Trueman’s, in his final evaluation of that application: “We need not anticipate setting widespread precedent, since poets of the calibre of those chosen would not be likely to wish to attend readings except where an important audience is to be found.”45 Trueman’s judgement appears to hold true for several years following the Contact Readings grant in 1959. The Poetry Series at Sir George Williams University (SGWU) arrived at a pivotal moment for the Council, as only a handful of grants were given out prior to 1966/67. In that year, starting with the Poetry Series at Sir George Williams, a new wave of readings emerged and worked collectively to establish a network of reading series across the country and to assert the value of funding such activities. Beginning in 1969, the rapid and widespread growth of poetry readings across Canada began to register at the Canada Council. Between 1959 and 1968, eleven grants were made to fund poetry readings. Twelve were made in 1969 alone. 189 grants would be made only seven years later in 1976/77. Poetry readings had successfully moved from occupying the marginal position of the “etc.” in “Opera, Theatre, Ballet, etc.” to receiving the dedicated category “Public Readings by Canadian Writers.”

The spread of readings across Canada strained the limited resources of the Council. In the case of the SGWU Poetry Series, the increased demand (despite increased total funding) contributed directly to the end of the series. Organizer Howard Fink recalls:

…we weren’t trying to prove anything, but you sort of hoped that it had been useful and the proof that it had been useful, finally the strongest proof was when [Naim Kattan, Literature Officer at the Canada Council] wrote me back the last year and said, ‘we can’t give you as much money as you want this year. When you started you were all alone…’and that was the last year and we didn’t do it anymore. Well there were poetry readings he said across the country and they had to share it out.46

Between 1957 and 1977, the Canada Council awarded $570,563.00 to facilitate literary readings across Canada.47 The intervention of the federal government in the development of the Arts following the Massey Commission and the creation of the Canada Council after the Second World War have been the subject of much scholarly and artistic criticism. The implications and stakes of the use of funding that is granted and spent in a framework as explicitly nationalist as the Canada Council is a necessary site of investigation. However, this ongoing analysis requires material historical grounding. An investment of $570,563.00 in poetry readings over twenty years is significant and is responsible for making at least some measurable headway in combating the geographical isolation endemic to the experience of Canadian writers in the middle decades of the previous century. Canada Council funding played a substantial role in facilitating the growth of poetry readings while simultaneously fostering the work of small presses and little magazines. However problematic this funding is, a significant portion of the literary exchange of these decades was only possible in the form that it eventually took because of the influx of Council money.

Institutions like the Canada Council and university English departments hierarchize knowledge and culture by privileging certain forms of production by way of grants and study. Funding one practice encourages others to apply for similar funding, thus establishing precedents and contributing to the evolution of the habitus of the cultural field. Canadian Literature emerges in the 1960s and 1970s as a visible cultural formation alongside its establishment as a viable academic discipline. The Canada Council was central to both of these processes, supporting artistic and scholarly work. By looking closely at one site among the diverse concurrent processes, one can discern a moment of growth and development in the emergence of the poetry reading as a new form of literary expression that the Canada Council recognized, as well as the mechanics of cultural policy that gradually shape such a new form into a more fixed and controlled cultural process. This paper has traced one dimension of the ever-changing historical conceptions of the “literary” in Canada in the twentieth century by documenting the specific material economic conditions that facilitated the widespread establishment of public readings as a form of literary expression.

This study also returns some humanity to institutions more often written off as unthinking bureaucracies by focusing on individual decision-makers and their interactions with cultural agents. While the funding of poetry readings would grow increasingly bureaucratic by 1977 as they became more widespread and funding categories became established, the earliest manifestations in 1959, 1960, and 1961 offer a model of cultural funding and policy that, due to its small scale and relatively small financial stakes, was able to respond directly and personally to the needs of artists and other cultural agents. It displays a form of thoughtful, engaged, and responsible cultural policy development, the results of which can be measured and evaluated, in part, in material terms. Given sufficient time and financial resources, one could trace who travelled where and when across Canada during these decades in order to map what was accomplished with the Council’s investment. Such a mapping would show the circulation of bodies that followed from Canada Council funding to form part of the “complex discursive assemblage” of poetry readings.48 Poetry readings require the movement of human bodies and as such require greater financial investment than the movement of books and literary magazines. Readings, unless hyper-local, necessarily consume more resources than these other, previously more common forms of literary expression. The Council enabled the circulation of hundreds, if not thousands, of human bodies in these years to read poetry out loud. Regardless of the valid criticisms that have been regularly levelled at the Council since its inception, this funding was vital in establishing poetry readings as important forms of expression in Canadian literary fields.

A first draft of “Theses on Discerning the Reading Series” was distributed to participants in the Approaching the Poetry Series Conference (Concordia University, April 2013) in the weeks leading up to the proceedings. ↩

Camlot and Wershler, “Theses,” 1. ↩

See Pauline Butling and Susan Rudy’s Writing in Our Time: Canada’s Radical Poetries in English (1957–2003) (2005), Robert David Stacey’s (Ed.) Re:Reading the Postmodern: Canadian Literature and Criticism After Modernism (2010), Barbara Godard’s Canadian Literature at the Crossroads of Language and Culture (2008), Frank Davey’s Surviving the Paraphrase: Eleven Essays on Canadian Literature (1986) as entry points to this discussion. ↩

Report on the Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences 1949–1951 (Ottawa: Edmond Cloutier, 1951), xi. ↩

Report on the Royal Commission, xi. ↩

Ken Norris, The Little Magazine in Canada 1925–80 (Toronto: ECW Press, 1984), 77. ↩

Quoted in Butling, Pauline and Susan Rudy, Writing in Our Time: Canada’s Radical Poetries in English (1957–2003) (Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2005), 45. ↩

Camlot and Wershler, “Theses,” 4. ↩

Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature (New York: Columbia UP, 1993), 42. ↩

Barbara Godard, “A Literature in the Making: Rewriting and Dynamism of the Cultural Field” in Canadian Literature at the Crossroads of Language and Culture, ed. Smaro Kamboureli (Edmonton: Newest Press, 2008), 279. ↩

Butling, Writing in Our Time, 41–42. ↩

Butling, Writing in Our Time, 43. ↩

Butling, Writing in Our Time, 44. ↩

Frank Davey, Reading Canadian Reading (Winnipeg: Turnstone Press, 1988), 100–101. ↩

Butling, Writing in Our Time, 43–44. ↩

Wershler, Darren, “Barbara Godard vs. The Ethically Incomplete Intellectual,” Open Letter 14:6 (2011): 109–110. ↩

Wershler, “Barbara Godard,” 120. ↩

Canada Council for the Arts, Third Annual Report (Ottawa: Canada Council, 1960), 82. ↩

Readers included Leonard Cohen, Denise Levertov, Al Purdy, Charles Olson, Cid Corman, Leroi Jones, Louis Zukofsky, Robert Creeley, Miriam Waddington, Margaret Avison, Diane Spiecker, Frank O’Hara, and many others. ↩

Kenneth McRobbie to The Secretary, Canada Council, May 20, 1959, Raymond Souster Fonds, Thomas Fisher Rare Books Library, University of Toronto, MS00203, 25. ↩

Kenneth McRobbie to Dr. A.W. Trueman, May 30, 1959, Raymond Souster Fonds, Thomas Fisher Rare Books Library, University of Toronto, MS00203, 25. ↩

Peter Dwyer to Water Herbert, July 3, 1959, Canada Council for the Arts, Ottawa. ↩

Walter Herbert to Peter Dwyer, July 13, 1959, Canada Council for the Arts, Ottawa. ↩

Canada Council for the Arts, Third Annual Report (Ottawa: Canada Council, 1960), 26. ↩

Peter Dwyer to Kenneth McRobbie, September 1, 1959, Raymond Souster Fonds, Thomas Fisher Rare Books Library, University of Toronto, MS00203, 25. ↩

Canada Council for the Arts, Third Annual Report (Ottawa: Canada Council, 1960), 26. ↩

Canada Council for the Arts, Third Annual Report (Ottawa: Canada Council, 1960), 26–27. ↩

Milligan, Frank, “The Ambiguities of the Canada Council,” in Love and Money: The Politics of Culture, ed. David Helwig (Ottawa: Oberon Press, 1980), 79–80. ↩

Milligian, “Ambiguities,” 80. ↩

Robert Fulford, “The Canada Council at Twenty-Five,” Saturday Night, March 1982, 40. ↩

Fulford, “The Canada Council,” 37. ↩

Mark Kristmanson, Plateaus of Freedom: Nationality, Culture, and State Security in Canada 1940–1960 (Don Mills: Oxford UP, 2003), 95–136. ↩

Canada Council for the Arts, Third Annual Report (Ottawa: Canada Council, 1960), 82. ↩

A.W. Trueman, “Endowment Fund Application 1961,” Canada Council for the Arts, Ottawa. ↩

Paul Litt, “The Massey Commission, Americanization, and Canadian Cultural Nationalism,” Queen’s Quarterly 98:2 (Summer 1991): 378. ↩

Dilys Hankins, “Towards a National Theatre: The Canada Council 1957–1982,” The Journal of Arts, Management and Law 14:4 (Winter 1985): 31. ↩

Report on the Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences (Ottawa: Edmond Cloutier, 1951), 225. ↩

Report on the Royal Commission, 225. ↩

Report on the Royal Commission, 377. ↩

Report on the Royal Commission, 377. ↩

Robert Lecker, “The Canada Council’s Block Grant Program and the Construction of Canadian Literature,” English Studies in Canada 25:3/4 (1999): 439. ↩

Lecker, “The Canada Council,” 441. ↩

Lecker, “The Canada Council,” 441. ↩

Lecker, “The Canada Council,” 441. ↩

A.W. Trueman, “Endowment Fund Application 1959,” Canada Council for the Arts, Ottawa. ↩

Howard Fink, Interview with Jason Camlot. SpokenWeb. November 2, 2012. ↩

It should be noted that this number is derived from the Council’s published annual reports. It was beyond the scope of this paper to investigate whether every single dollar granted was ultimately claimed and spent by the individual applicants. ↩

Camlot and Wershler, “Theses,” 1. ↩

Article: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.