This body is a technoliving, multiconnected entity incorporating technology. Neither an organism or a machine, but ‘the fluid, dispersed, networking techno-organic-textual-mythic system

–Paul B. Preciado, Testo Junkie

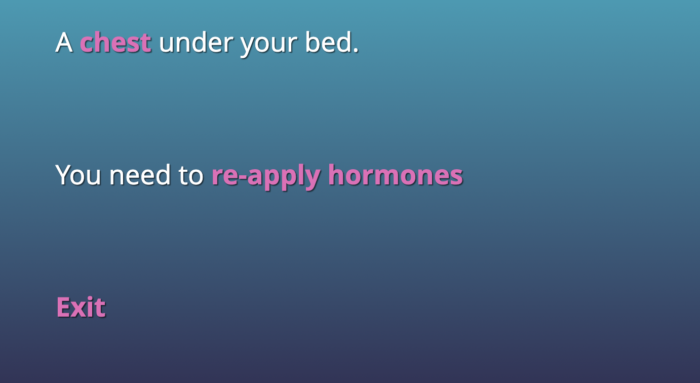

I feel lost, aimless, and tired as I click through the hypertext pages of Porpentine Charity Heartscape’s 2014 Twine narrative, With Those We Love Alive.1 I’m in the city, even though the pages all look the same. White text, pink links, sometimes purple ones, a blue gradient background. I’ve been here before. To the city, I mean. Was it yesterday? Two days ago? Not sure. I keep clicking. I watch things in the dry canal. Grotesque things. Freak things. Urchins, rat kids, an angel corpse, sewer ooze. I can either continue to watch or look away. “Look away.” Next, I navigate to the maze-like alley. I’ve been here before too; it’s a dead end with a puddle of green slime and nothing to do or click. Most of the interactive fiction is like that. Nothing to do but sleep and work. Today’s different though, today “A Slime Kid is here.” The next ten minutes or so we spend together are joyful. This Slime Kid, who seems to have leaked in through the cracks in the alleyway stone from nowhere, plays with me, spattering slime and oozing back together. “Yay” (Fig. 1). Where did she come from? I’ve never seen her before. Curiosity gets the best of me as I right-click the webpage to see the program’s source code. A quick page search for “slime” and I see it, “if $hormone_day is 4…a [[slime kid]] is here” (Fig. 2). She came from hormones. These moments remind me of Susan Stryker’s somatechnics and Paul Preciado’s assessment of the hormonal body as techno-fluid “chemical traffic” distributed across biopolitical capitalist networks; hormones are technical matter capable of constructing novel and multiple relations across bodies, even in the most unlikely of places.

Fig. 1: A screen capture from With Those We Love Alive depicting one of the Slime Kid’s playful interactions.

Fig. 2: A screen capture from With Those We Love Alive’s source code. When the variable $hormone_day reaches day four in narrative time, the Slime Kid can be found in the maze-like alleys of the city.

Since they were first named into existence nearly 120 years ago at the time of publication, hormones have been considered meaningful biological mediators, “chemical messengers” that flow and leak into, out of, and between bodies. Hormones’ biochemical roles are semiotic and agential, as they are able to execute certain processes and procedures that make the medicalized body legible through social frameworks such as gender, race, disability, and illness. Throughout the twentieth century, steroidal hormones became an experimental tool with which the scientific community could make claims about the sexual modalities possible for hormonal life. As chemical codes, hormones have increasingly influenced the legibility of the body. Critical assessments of twentieth-century endocrine science continue to emphasize hormones’ semiotic capacity. Nelly Oudshoorn’s Beyond the Natural Body and Celia Roberts’ Messengers of Sex provide critical analyses of the capitalist power structures that dictate how hormones, and knowledge claims about them, flow through medical, social, and ecological organizations. In Testo Junkie, Paul Preciado situates the techniques and technologies of hormone capitalism firmly in postmodernity as he argues that hormones, both “chemical traffic” and chemicals that are trafficked,2 are semiotic matter which flows through the distributed protocols and procedures of a biocapitalist pharmacopornographic regime. More recent scholarship in trans studies further nuances these arguments. Malin Ah-King and Eva Hayward demonstrate how hormones’ ongoing processes of sex- and gender-making produce a shared condition of vulnerability in networked relations between bodies and environments.3 Writings by both Jules Gill-Peterson and Hil Malatino emphasize hormones’ technical capacities4 to mediate and make meaningful the human hormonal body by tracing its (oftentimes) eugenic histories of sexual, gendered, and racial plasticity5, and by identifying it as a site for intervention through procedural logics like “hacking.”6 Though tackled in different contexts and from various disciplinary methods, scholarly meditations on hormones, particularly in the humanities and social sciences, recognize this matter as both agential and operational in its flows across embodied relations.

My reading of With Those We Love Alive is informed by micha cárdenas’ scholarship on algorithmic analysis. As a literary method, algorithmic analysis shares a premise with critical code studies that coded text holds meaning beyond its immediate function or procedure.7 In Poetic Operations, cárdenas emphasizes how algorithmic analysis offers an approach to thinking through the “complex processes of identity and oppression”8 with a focus on trans of color poetics produced through these operations. Porpentine is a trans woman, though not a woman of color, but, as cárdenas notes, these specific intersections of identity are not prerequisite for performing trans of color poetics through computer code.9 However, the materialist approach in Poetic Operations remains founded in an ethos of survivability through the coded movements, operations, and transformations well-known to those who move through precarious and shifting identities. Informed by cárdenas’ work, which uses algorithmic syntax as part of her practice to “bring [trans] experiences to life through poetry and performance,”10 I take the mediation of ‘hormone mediation’ quite literally, offering a close reading of how Porpentine codes hormones as variables in her program and how those encodings inform narrative outcomes either toward or against the reproduction of oppressive violence. In the latter case, I discuss how a variable in the program’s code called “$hormone_day” acts as a poetic operator, producing joyful and kin-based engagement in opposition to the oppression that defines much of the trauma-bound environment of With Those We Love Alive.

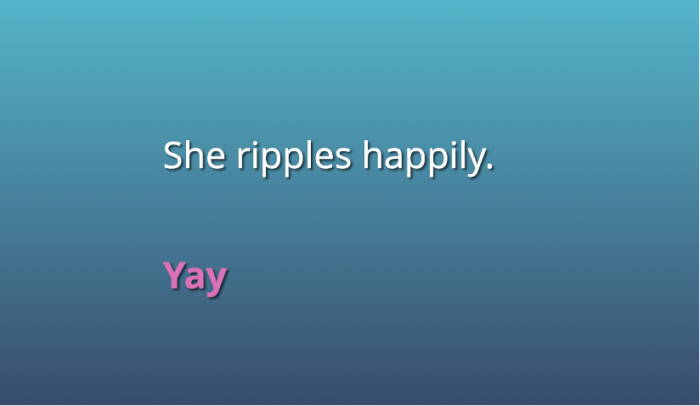

While I do stress the coded values of hormones, my reading of these “chemical messengers” does not rely only on the medicalized body as a site to trace the power, affects, and subjugated positions that come out of hormonal relations. Rather, I look at how a hypertext narrative about trans life, standardization, and complacency uses hormones to either reproduce or subvert these politics by coding hormones through a digitally embodied protocol, rather than an explicitly biochemical one.11 I offer a close reading of the time-keeping variable, $hormone_day in the program code of With Those We Love Alive. In computer programming, variables act as containers that store values while a program is running. In With Those We Love Alive, $hormone_day stores information about narrative time by counting in-game days through a seven-day loop. Letting the playable character sleep increases the value of $hormone_day by one. After $hormone_day reaches a value of ‘7’ readers must apply a weekly dose of feminizing HRT pharmaceuticals in the forms of estroglyphs (in-game estrogens) and spiroglyphs (in-game spironolactone) before they can move on to the next day by sleeping, which resets the value of the variable back to ‘1.’ As mentioned at the outset of this paper, $hormone_day also determines the Slime Kid’s presence when the value of the variable reaches ‘4.’ In this way, With Those We Love Alive operates through a narrative ontology in which working towards progress and encountering certain features of the world are contingent on hormonal value.

Porpentine’s decision to base her narrative progression on hormone variables is not an unfounded representation of the endocrine system. Hormones themselves are rule-bound agents that inscribe on bodies as textual media. Since the turn of the twentieth century, when British biochemists Ernest Starling and William Bayliss first proposed hormones as the body’s biochemical agents, these various substances have been framed as chemical messengers, subject to specific condition-based rules of the body in order to achieve a sustained equilibrium or “homeostasis”12 of endocrine levels. But the rules they follow are themselves subject to management and standardization. With increasing development and circulation of hormone protocols through what Preciado calls the “pharmacopornographic regime,” hormones as technical matter have been leveraged by biocapitalism to produce “subjects on a global scale.”13 With gender-reaffirming therapies, anti-depressants, fertility treatments, and so forth, these subjects are made valuable to capitalist control not just as consumers of hormones, but as ideal hormonally-mediated subjects ready to participate in both public and private labors.

With Those We Love Alive’s use of the variable $hormone_day brings attention to hormone’s technical capacity to produce subjects through procedure, whether digitally or biochemically. In what follows, I offer close readings of two notable events controlled by $hormone_day; the first is the need to re-apply hormones on day ‘7’ before any other action towards narrative progress can be taken and the second is the presence of the ‘easter egg’ character Slime Kid on day ‘4.’ While the act of reapplying hormones in a narrative inflected with themes of trans life may seem a like a moment of self-actualization and gender euphoria, taking these hormones is rendered laborious through a procedural rhetoric in which the most efficient and complacent modes of progressing through the narrative reproduce the violence of the trauma-bound environment. In contrast, Slime Kid, who comes from no pharmaceutical capitalist regime, but is nonetheless a product of hormonal relations in the narrative’s ontological framing, is a product of inefficient modes of play who brings moments of joy and reprieve to the reader. Ultimately, this essay challenges a contemporary understanding of hormones in which productions of hormonal meaning are limited to the sites and contexts of the medicalized body. By recasting the coded value of “chemical messengers” as procedural, digital operations, through texts like With Those We Love Alive, we might better understand how hormonal relations inscribe across all sorts of bodies without necessarily reproducing biomedical subjectivities.

Narrative Progression: A Procedural Rhetoric of Alienation

With Those We Love Alive was developed by Porpentine Charity Heartscape in 2014 and has received critical acclaim.14 The game is a hypertext narrative made with Twine, an open-source software for writing interactive fiction that enables storytellers of all programming experience to build their fictions in HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. Set in a dark fantasy world controlled by a larval and “ichorous” Skull Empress, With Those We Love Alive depicts an environment where the tyranny of the Empress depends on her subjects’ complacency with the various types of violence which drive her oppressive regime. As an interactive fiction, this complacency is not limited to diegetic storytelling. Rather, it is enacted by the reader through the procedural affordances of hypertext narratives.

Specifically, readers are guided to move through the narrative and its world paying little attention to interactive events outside of the Empress’ demands or how the playable character does or does not conform to them. This reading reproduces a capitalistic mode of interaction with the work, effectively alienating readers from the story and its world. The procedural rhetoric that suggests linear reading modes and efficient narrative progressions are the intrinsic reward for engaging with the story persuades the reader, ironically, to disengage from close and careful readings of Porpentine’s dark fantasy world. Readers who follow the most linear and ‘efficient’ route to narrative completion, where such progression is contingent on increasing the value of $hormone_day through the sleep action, end up reproducing the oppressive and alienating effects of the Empress’ regime through their complacent and disengaged reading.

Interactive fictions are procedural texts. They follow rules that determine how, with what, and when readers can interact in their stories. Common interactive fiction practices like procedural linking15 (using text that describes a new action to progress the narrative), conversational linking (using dialogic responses to progress the narrative), cyclical linking16(cycling through a series of text options so readers can customize aesthetic features of the narrative), and node-based, non-linear narrative design inspired by Choose Your Own Adventure (CYOA) storytelling combine diegetic practices (narrative) with rules-based and interactive design (ludic) to create storytelling experiences that adhere to what Ian Bogost calls a procedural rhetoric; the “practice of persuading through processes.”17 In With Those We Love Alive, readers face a procedural rhetoric through linking structures and in-game repetition that encourages alienation and isolation from the Empire on the one hand, and participation in violence as a means of escaping isolation on the other. Though these choices have no influence on the outcome of the story, readers are persuaded toward either alienation or violence because choosing, and thereby following the narrative’s linking structures, entices readers with the promise of narrative progression; a reward for playing by the rules.

Readers of With Those We Love Alive assume the role of an artificer who is tasked with making weapons and accessories for a tyrant Skull Empress. The narrative is mapped across webpages called “passages” in Twine’s programming. Navigating through these passages generates opportunities to interact with different objects, events, and locations. Assuming the role of the playable character, readers of With Those We Love Alive can choose to visit a number of areas in the Skull Empire, including the city, their character’s chambers, and their character’s workshop where she is tasked with making accessories for the Empress.

Reading With Those We Love Alive requires clicking links. The story establishes an aesthetic protocol for these links as a way of procedurally directing readers towards narrative progression.18 White text indicates prose, purple texts are cycling links that loop through a set number of aesthetic descriptors, and procedural and conversational links that move readers through passages are pink. Readers have some constrained agency in their exploration of the narrative world. For example, cycling through descriptive purple links changes the specific poetics of the story, even if it doesn’t alter the narrative’s general aesthetics of all things grotesque. For instance, to establish the playable character’s name, readers are asked “What is your element?” and can choose their answer from the cycling options; Petal, Tears, Mud, Machine, Fur, and Feathers. In another example, when the playable character is instructed to craft an accessory for the Empress within the first three days of servitude to her, readers may choose to craft a Diadem, Gauntlet, or Mask made of Heretic Bone, Dronesteel, or Lake Crystal (Fig. 3). Porpentine’s poetics are pre-determined in the program, rather than generative. However, through the affordances of interactive text, she presents these fragmented moments in such a way that the order, timing, and visual emphasis and de-emphasis on particular words, phrases, and sentences produce what Inge van de Ven calls “a non-linear reading with fleeting attention” that at the same time “wears its rules [of] notice on its sleeve, as it explicitly indicates when it pays off to pay attention [to] and close read” both content and the mechanics of form.19 Thus, readers of With Those We Love Alive are able to produce multiple and various understandings of prosody and plot through negotiations with the narrative constraints at hand.

Fig. 3: A screen capture from With Those We Love Alive depicting purple cycling links for customization of the narrative poetics, white prose, and pink procedural links.

One soon comes upon limitations to the story’s scope and types of interaction they might experience in it. Many pages contain just a few lines of prose or poetry followed by a single pink link to move forward. Navigating through the interactive design of With Those We Love Alive often feels like work. Readers are not often rewarded with new information or options when they visit sites or interact with objects multiple times over the course of the narrative, fostering a “fleeting attention” to much of the worldbuilding. Interaction exhausts itself quickly with much of the world soon feeling like an amalgamation of stagnant set pieces, rather than vibrant and interactive.

With Those We Love Alive emphasizes various embodied engagements with its text. Occasionally, readers are asked to draw ‘sigils’ on their skin with a pen, marking their own flesh in response to the events in the narrative; an action that can be read as a trauma response analogous to self-harm practices or other physical augmentations to one’s body.20 Though less immediate, navigating through the hypertext by clicking links is not any less embodied or laborious; on most in-game days, readers move through the world rather uneventfully, only progressing the story by going to the playable character’s chambers and sleeping, increasing the value of $hormone_day in order to advance the narrative. Unlike some other CYOA structures, few other actions hold bearing on the story’s outcome or the subplots readers engage with along the way. Particularly impatient readers who are not keen to explore the world could very easily engage in a reading of With Those We Love Alive that emphasizes the depressive mundanity of life under rule of the Skull Empress, spending much of narrative biding time before being called to labor for the Empress once again. In this reading mode, one could finish the story by sleeping it away, a procedural realization of the depressive and dissociative state of the playable character within this world.21 This way, readers would never need to have the playable character leave her chambers unless other in-story events, such as re-applying hormones, making weapons and other adornments for the Empress, special princess spore-killing ceremonies, or the return of a long-lost friend, require readers to take action before returning to sleep. In taking the smoothest path towards story progression, readers will face more actions that support the violence of the Skull Empire with fewer moments of relief.

The timekeeping structures that measure narrative progression within With Those We Love Alive not only emphasize a fantastical interpretation of Arendtian banalities of evil, they also allow readers to embody them. Ludonarrative time is organized through in-game days. Similar to a standard calendar week, the value of the variable resets to ‘1’ after every seven sleeps. When readers sleep, $hormone_day advances by a value of one. When $hormone_day reaches a value of ‘7,’ the playable character must re-apply a dose of hormones before advancing the story (Fig. 4). This relationship effectively congeals an otherwise meaningful moment of gender affirmation, taking HRT, into just another act of labor for survival performed by the playable character. After applying hormones, readers can sleep until the next day, resetting $hormone_day to ‘1’ and continuing the sleep-work cycle that dictates story events (Figs. 5 and 6).

Fig. 4: A screen capture of With Those We Love Alive’s source code. This line indicates that the playable character will have to re-apply hormones ($hormone_need=true) when the variable $hormone_day reaches day seven in narrative time.

Fig. 5: A screen capture of the chambers passage in With Those We Love Alive on most in-narrative days.

Fig. 6: When $hormone_day reaches a value of ‘7’ in With Those We Love Alive, the option to sleep is not available until the reader re-applies hormones.

As narrative progression is contingent on readers taking the sleep action, an action which changes the value of the interactive fiction’s time-tracking variable, and because the time-tracking variable itself was designed by Porpentine to reflect hormonal states, With Those We Love Alive is best understood through an ontological framing that privileges attention to mediating hormonal relations across time, events, and interactions. However, this privileged attention to hormones does not necessarily result in hormone treatments that reflect the community-based praxis of trans care and kinship outlined by Malatino in Trans Care. On the contrary, the subsumption of hormone therapies into the labor cycle of With Those’s affective narrative play erodes any presumed sense that HRT alone is sufficient trans care and renders taking HRT as a sort of “minimal [form] of survival” needed to sustain the playable character (and the reader) as co-operative laboring subjects before they return to working for the Empress.22

Re-applying hormones in With Those We Love Alive does not feel like a celebratory moment of gender euphoria. Though readers are told the estroglyphs and spiroglyphs are “precious” when looking at the drugs in a chest, the only reaction offered to advance the game after taking the hormones is “okay” (Fig. 7), rendering the act an entirely underwhelming experience. Taking hormones feels like work. This labored relationship between hormone re-application and affective alienation under indentured servitude to the Empress is exemplary of Preciado’s understanding of pharmacocapitalism as the global colonial engine that turns bodies into both commodities and ideal subjects. For instance, from the perspective of those reading With Those We Love Alive, estroglyphs and spiroglyphs are most transformative for the playable character not as self-actualizing matter, but as subject-making, insomuch as they produce a character willing to continue the narrative through alienating sleep-work cycles that demonstrate a complacency with the Empire’s violence.

As a time-keeping variable, $hormone_day suggests an ontology in which the value of hormone relations determine time, events, and interactions in the dark fantasy world of With Those We Love Alive, and how With Those We Love Alive invokes a procedural rhetoric which encourages readers to advance the narrative by performing limited actions which produce an alienating mode of reading the text. This mode of reading produces a type of labor embodied by the reader clicking the sleep action, and advancing the values of $hormone_day, to reach the next novel event, such as crafting something for the Empress, or until they must make the playable character re-apply HRT. In this way, $hormone_day creates a contingency between taking HRT and the alienation of progress-oriented reading modes in With Those We Love Alive’s trauma-bound setting. Taking HRT becomes a task one needs to complete before they can return to work, further progressing the story. However, the ontological framework invoked by the $hormone_day variable does not exclusively posit hormones as subject-making by violent means under violent regimes. Despite this, Slime Kid, an easter-egg character whose presence suggests some of the most joy and relief from trauma within the game, is product of both $hormone_day and modes of reading that forgo a logic of linearity and progress.

Finding Joy in Slime Kid: Coding Hormones as Community Care and Praxis

The violence of With Those We Love Alive is countered by moments of intimacy and care between the two trans-coded, trans-femme characters. Readers who are familiar with the plot of With Those We Love Alive will know that the ultimate narrative resolution is achieved when the playable character reunites with a long-lost friend and fellow victim of the violent regime. Together, they restore each other’s sense of self, share romantic moments, plan a rebel attack on the Empress, and escape her control.23 These moments are essential to With Those We Love Alive’s allegorical position against coercive and disciplinary regimes. However, they are not the only moments which emphasize community-based care against a conformity to and complacency toward violence in the story.

The Slime Kid, who appears in the city’s alleys only on days when $hormone_day stores a value of ‘4’ (i.e., four ‘sleeps’ after re-applying estroglyphs and spiroglyphs), is similarly a product of the interactive fiction’s hormonally-determined ontology. Unlike the alienating affects produced by readings toward narrative progression, the Slime Kid is a product of hormone relations who exists outside the logics of efficiencies, hegemonic progress, and pharmacopornographic subject-making. The only way to engage with the Slime Kid is to find her ‘hidden’ at a moment and place within the narrative world where engagement has no consequence on programmed in-story events. This is not to say that her presence has no consequence of possible readings of the text. The Slime Kid’s presence in the narrative is an altogether joyful one, a stark opposition to the dreary aesthetic so thoroughly established elsewhere across the narrative. When readers do find her, if they find her, all possible programmed interactions with the Slime Kid elicit a sense of relief as she provides community and care outside of the control of the Empire.

When interacting with the character, the reader will experience the Slime Kid performing one of fourteen activities. She gurgles, spraying slime on your boots; She kisses a bug; She shows you a drawing she made. It’s very good; She climbs around on the wall for a while, sticking to it like gum; She shows you how to puff up to scare your enemies. Your body doesn’t stretch as much, but you promise to study hard; She’s [digests] a piece of trash; She pops like a bubble, spattering slime everywhere, then oozes back together, giggling; She hugs a snail; She turns into funny shapes then falls over; She [helps] a bug find a home; You teach her some melter tricks; She pretends to be a puddle; She [draws] on the wall with a piece of chalk she found. The whole wall is covered with rain-faded smears of soft pastel; She ripples happily. The only available text reaction to these childlike performances is “Yay” (Fig. 8). The reader has no choice but to celebrate and share in the play, joy, compassion, mutual teaching, and love offered by the Slime Kid. Unlike the weekly applications of estrogylphs and spiroglyphs in With Those We Love Alive, the Slime Kid’s hormonal presence signals the necessity of complex and integrated care and aftercare practices “in the wake of profound recalibrations of subjectivity and dependency” beyond the therapies for which access is so often institutionally controlled.24

Though the narrative is not explicitly autobiographical, I do read the Slime Kid as a sort of cameo or self-insert by Porpentine in an attempt to allow her reader a moment of reprieve from the narrative’s main focus on trauma, violence, and complacency. During my first encounter with her work, Porpentine’s online brand and alias was “Slime Daughter,” a slime kid of sorts.25 If readers are to take the Slime Kid’s hormonal origins earnestly, as I believe they should, her existence also stands in a long history of community-based and -dispensed trans hormone therapies now commonly referred to as ‘trans DIY’ practices. The self-appointed doctors of trans DIY communities have been and continue to be mostly made up of trans feminine and trans women of color who frequently risk their safety to provide trustworthy, compassionate, and effective care for their community in direct opposition to the pathologizing, poor-quality, and inaccessible, or otherwise non-existent, care available through licensed medical practices, particularly in the United States.26 Slime Kid’s kinship-based care in With Those We Love Alive challenges the presumed efficacy of the narrative’s pharmaceutical hormones to provide the best care for both the reader and the playable character.

This community-based and anti-capitalist ethos is further reinforced by Porpentine’s continued use of Twine and her participation in the Twine community. As a tool for designing and telling interactive stories, Twine democratizes modes of visual storytelling that are often considered exclusive to mainstream game-makers.27 Namely, Twine is made accessible to programmers of varying experiences through its easily understood editing interface. Community members, including Porpentine herself, will often readily share their techniques for more complex programming beyond the platform’s basic documentation with beginners.28 Twine is known for its community of queer creators. The accessibility of the platform and the ‘shareware’ fictions and games one can make with Twine has created a space for a plurality of voices to participate in the digital creation and distribution of ideas, stories, and polemics, not through the often-hostile spaces of ‘mainstream’ game development, but through a cultural politics that shares its genealogy with print media counterparts like zines and other types of pamphleteering.29 The social rules and functions established within Twine’s community of designers generally follow a refreshing ethics of care and kinship in digital spaces where, more often than not, “racism and sexism are part of the architecture and language of technology.”30 The culture fostered by these tools exemplifies a crucial aspect of the political project of trans care practices as argued by Malatino; to demand and create a redistribution of the power enjoyed by those in hegemonic spaces.31 As such, creators who exist at the intersections of 2SLQBTQIA, BIPOC, disabled, and otherwise ‘queered’ identities, often turn to Twine and similarly accessible and distributable software as favourable tools for producing works that “resist commodification” of mainstream game development.32

The Slime Kid offers readers a rare moment to celebrate the playfulness and curiosity of a hormonally-determined embodiment, particularly the experience of a certain jouissance amidst the agony of coming into adolescence (and perhaps not her first adolescence) indicated by her ‘Kid’ status. Notably, Slime Kid’s youth is presented without the threat of what Edelman calls reproductive futurism.33 Slime Kid is not given to us as progeny, she is a kid but no one’s child. Instead, she emerges from a coding hormone message that redirects reader action away from the alienating labor that pushes the reader toward a sense of narrative completion through complicit violence. A sort of femme-trash, cyberpunk, Benjaminian figure, Slime Kid resists the futurist promise of progress.34 A product of hormonal logics recuperated from biocapitalist power; her slimy presence seems to literally leak out of fissures in the otherwise violent organizational structures of the Skull Empire. Leaks expose cracks and create inefficiencies in controlled flows.

Meandering readerly modes that allow readers to find Slime Kid in the alley demonstrate a similar sort of inefficiency as they forgo the alienating experience of a teleological reading. In this way, entertaining the Slime Kid’s presence is both an act of resistance against readerly tendencies aimed toward linear, narrative progress and a reminder that the complex webs of hormonal care exist outside of and beyond biomedical subjectification. Her presence is always in opposition to the biocapitalist ethos that directs readers toward narrative efficiencies and progression. Her kinship is based in hormone relations that affectively mediate through interaction and interfacing rather than in taking (re)productive routes.

Conclusion: The Poetic Operations of Hormones

The Slime Kid’s presence as a product of $hormone_day underscores a politics of trans care found in queer sharing of hormone experiences. By organizing diegetic time as a hormone operation, Porpentine leverages the interactive affordances of Twine to create a world where hormonal interaction determines readers’ affective experiences with the narrative. These responses mimic the vastly different understandings between colonial institutionalized medicine and community-based practices of what sorts of processes and interactions might constitute ‘care.’ What’s more, while teleological readings must engage with HRT as a routine means to an end, slow careful reading modes that engage with the Slime Kid’s kinship understand care via hormonal mediation as a mutable, non-linear and always incomplete process.

It may be tempting to discount the hormone relations depicted in With Those We Love Alive, both in-narrative and in the code that organizes it, as simply figurative and therefore trivial to any political concerns about hormone’s flows and access in our ‘real world.’ All hormones are already semiotic, regardless of their representation as digital programming or by molecular structure, and that given the emphasis on the embodied affects of hormone operations in With Those We Love Alive, my hope is that “symbolic” is not confused with “immaterial.” Porpentine’s decision to base her narrative progression on coded hormone variables is not an unrealistic representation of the hormones as procedural matter. Hormones are agential matter and the bodies they construct are susceptible to managed flows of traffic in distributed hormone networks. In other words, hormones are tools easily leveraged in processes of subjectification. Turning to an algorithmic analysis of With Those We Love Alive that understands the $hormone_day variable as a political operator, both able to reinforce and resist dominant forms of medicine and care, helps bring to life the mediating power of hormones as biochemical agents. Hormone operations assume an embodied intertextuality between the subject and biochemical mediation. These are the same sorts of intertextual relations that are encoded in Porpentine’s storytelling through affective and distinctly embodied reading modes. The hormone relations offered to us through the Slime Kid character resist reproducing hegemonic encodings of the body—both hormonal bodies and bodies of texts.

By building a world where hormone messages determine how time is perceived and when intimately shared joy might occur, Porpentine’s hormone protocol is perhaps speculative in nature, but it is not at all fantastical. What if hormones produced kinship? The hormone-determined variable in her code represents a very real ontological position for people who depend on hormone therapies and use them to think themselves through time, space, and intimate relations. By bringing such ontologies to focus, With Those We Love Alive prompts me to consider what other kinds of hormone messages we can produce outside of dominant procedural action and the ways they might network hormonal life through multiple interpretations of chemical being. Porpentine’s formal and narrative aesthetics demonstrate how a playful and queer engagement with hormones and their mediating operations can enable a reparative encoding and decoding of hormone messages: the telling of new stories that readily attend to kinship as a product of hormone relations and resist the myth of progress as a product of labor by creating tactical inefficiencies.

You can read With Those We Love Alive on Porpentine Charity Heartscape’s website, https://xrafstar.monster/games/twine/wtwla/. ↩

Paul B. Preciado, Testo Junkie, Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era, trans. Bruce Benderson (New York, NY: Feminist Press, 2013), 159. ↩

Malin Ah-King and Eva Hayward, “Toxic Sexes: Perverting Pollution and Queering Hormone Disruption,” O-Zone: A Journal of Object-Oriented Studies 1, (2013): 1-12. ↩

Jules Gill-Peterson, “The Technical Capacities of the Body: Assembling Race, Technology,” TSQ 1, no. 3 (2014), 402-418, doi.org/10.1215/23289252-2685660. ↩

Gill-Peterson, Histories of the Transgender Child (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2018). ↩

Hil Malatino, “Biohacking Gender: Cyborgs, Coloniality, and the Pharmacopornographic Era,” Angelaki 22, no. 2 (2017), 179-190, doi.org/10.1080/0969725X.2017.1322836. ↩

Mark C. Marino, Critical Code Studies (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020), 9. ↩

micha cárdenas, Poetic Operations: Trans of Color Art in Digital Media (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 9. ↩

cárdenas, Poetic Operations, 25. ↩

cárdenas, Poetic Operations, 25. ↩

Porpentine Charity Heartscape, “Notes,” Electronic Literature Collection Vol. 3., (Cambridge, MA: Electronic Literature Organization, 2016), https://collection.eliterature.org/3/works/with-those-we-love-alive/notes.html. ↩

Walter B. Cannon, The Wisdom of the Body (New York: The Norton Library, 1963), 21-23. ↩

Preciado, Testo Junkie, 54. ↩

From Electronic Literature Collection’s feature of With Those We Love Alive: “ [Porpentine]’s won the XYZZY and Indiecade awards, had her work displayed at EMP Museum and The Museum of the Moving Image, and been profiled by the New York Times, commissioned by Vice and Rhizome, and she is a 2016 Creative Capital Emerging Fields awardee.” See, https://collection.eliterature.org/3/work.html?work=with-those-we-love-alive. With Those We Love Alive was also featured in the 2017 Whitney Biennial. ↩

Anastasia Salter and Stuart Moulthrop, Twining: Critical and Creative Approaches to Hypertext Narratives (Amherst, MA: Amherst College Press, 2021), 91. ↩

Salter and Moulthrop, Twining, 41. ↩

Ian Bogost, Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), 2-3. ↩

See Ian Bogost’s writing on “procedural rhetoric” in his book Persuasive Games (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007) or his chapter on “The Rhetoric of Video Games” in The Ecology of Games (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008) for an in-depth discussion of how interactive media persuades through protocollary design. ↩

Inge van de Ven, “Platform-based Rules of (Un)Notice: Digital literature and attentional modulation” (paper presented at the ELO 2021 Conference and Festival: Platform (Post?) Pandemic, Aarhus University, virtual conference, May 24-28, 2021, https://conferences.au.dk/fileadmin/conferences/2021/ELO2021/Full_papers/Inge_van_de_Ven_Platform-based_Rules_of_Notice__Electronic_literature_and_attentional_modulation__172.pdf. ↩

Alice O’Connor, “Physically Interactive Fiction: With Those We Love Alive,” Rock Paper Shotgun. Published November 14, 2014. https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/drawing-violences-mundanity-with-those-we-love-alive. ↩

Ian Bryce Jones, “Do(n’t) Hold Your Breath: Rules, Trust, and the Human at the Keyboard,” New Review of Film and Television Studies 16, no. 2 (2018), 177, ↩

Hil Malatino, Trans Care (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2020), 66. ↩

These characters are romantic but not explicitly sexual. They love each other but are not necessarily love interests to each other. In her notes, Porpentine states “WTWLA is a friendship between fems. The game’s metadata describes itself as a “romance” but nothing sexual happens, they don’t really flirt. I wanted to talk about romantic friendship, about intimacy outside of the binary of platonic/sexual.” ↩

Malatino, Trans Care, 3. ↩

You can engage with a variety of Porpentine’s creative works, including more interactive fiction and art, on her website, previously slimedaughter.com which redirects to her address at the time of writing, xrafstar.monster. ↩

Jules Gill-Peterson, “Doctors Who? Radical Lessons from the History of DIY Transition,” The Baffler, no. 65 (2022), https://thebaffler.com/salvos/doctors-who-gill-peterson. ↩

Alison Harvey, “Twine’s revolution: Democratization, depoliticization, and the queering of game design,” Game: The Italian Journal of Game Studies 3 (2014), 102, https://www.gamejournal.it/3_harvey/, 100. ↩

Harvey, “Twine’s revolution,” 98. ↩

Anthropy, Rise of the Videogame Zinester, 8. ↩

Safiya Umoja Noble, Algorithms of Oppression (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2018), 9. ↩

Malatino, Trans Care, 70. ↩

Harvey, “Twine’s revolution,” 103. ↩

Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Durham, NC :Duke University Press, 2004), 17. ↩

See Walter Benjamin’s writing on progress in “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” ↩

Article: Creative Commons NonCommerical 4.0 International License.