In his January 27, 2014 keynote speech at the AXS Partner Summit Snapchat CEO Evan Spiegel summarized the ethos and functionality of his company: “Snapchat discards content to focus on the feeling that content brings to you, not the way content looks.” Snapchat is a native mobile application that allows you to send “Snaps,” or text, photo, or video messages to friends in your contact list. The company is most well-known for messages and short videos that disappear after ten seconds, a feature that sets Snapchat apart from other social networking platforms, as Spiegel makes clear. The irony here is that his speech is documented on the company blog, the long-form archival medium the young company relies on to deliver a consistent public branding narrative. The blog repeatedly reiterates Spiegel’s central claim in the quote above: the real product that Snapchat is offering users is an experience. By minimizing the archive on the level of the interface and offering users the ability to quickly and easily manipulate photos, the app simply reflects, rather than shapes how a user feels at an exact moment. What Spiegel posits is that ephemerality is more than a gimmick, it is the material condition of a better, more authentic form of social media.

In the last two years, however, the company has also expanded its platform to include more long-lasting or archival functionality as well. Stories, for example, are compilations of photographs and short video clips edited into a typically chronological narrative of your day that can be viewed for 24 hours. Such tools suggest that even though Snapchat is known for its ephemerality, that construct is somewhat limited for describing the kind of media experience the app offers its users. As if to reflect this temporal tension, the company also recently changed its name to Snap, Inc. in order to recognize its growing status as a media company, for which Snapchat is only one product. And it is, by almost any measure, a successful media company. Founders Evan Spiegel and Bobby Murphy turned down a $3 billion buyout offer from Facebook in 2013 despite a lack of any real revenue. At the time of the offer, the company was surviving on two rounds of Venture Capital investment, but after its March 2, 2017 Initial Public Offering (IPO), the company was valued at $34 billion.1 And although the company released a disappointing earnings report in July of 2017, leading the stock price to drop 37% below its IPO price, research analysts and commentators remain optimistic about the company’s future because of its exceptional understanding of its audience.2 Bloomberg reported in June 2016 that the app has 150 million daily users, a higher number than Twitter.3 And nearly 45% of those daily users are between the ages of 13-17, suggesting the potential for both long-term growth, and growth within older demographics as well.4 One of the app’s earliest and most popular users is DJ Khaled, whose Stories average 3-4 million views, roughly the same number of people that tune in weekly for television’s most popular sitcom, The Big Bang Theory.5

While much of the press about the company heralds ephemerality as the factor driving its success, the company itself crafts a much more nuanced narrative that emphasizes the experience the app offers as its primary product. Through the company blog, surprisingly chatty company policies, and interface design, Snapchat positions ephemerality as merely one functionality it deploys to create a mode of social networking more organic to everyday life. Snapchat feels more authentic, these narratives argue, because it captures a spontaneous, unpolished, and temporary expression that more accurately reflects daily reality than the permanent and performative archival mode favored by other social networking platforms such as Facebook.

Although the critical literature on Snapchat is still at a very early stage, most scholars also describe the ephemerality of the app in terms of a relationship between presence and absence.6 A message exists and then it disappears. And as the app’s Cookie Policy explains, “delete is our default.” But as even a cursory examination of the Privacy Policy reveals, the company retains a massive archive of both content and metadata about messages, users, and devices. The archive is as central to the app as ephemerality. In this sense, defining the app as a tension between presence and absence quickly breaks down. What instead makes more sense is an exploration of ephemerality as a discursive framework, the construction of which reveals something important about where social media is today and where we imagine it is headed in the future. In her work on the reliance of metaphors in the scientific, cultural, and commercial discussion of the Internet, Sally Wyatt argues that these figurative phrases provide both a normative function and a horizon for the cultural imaginary.7 Tarleton Gillespie similarly argues that for Web 2.0 companies, the discursive appropriation of laden terms allows them to shape “a trope by which others will come to understand and judge them.”8 Ephemerality is thus a metaphor and trope the company has expertly crafted to signal an interval of attention that occupies a space between memory and forgetting, and suspends communication between the past and the present.

The app relies on durational forms of engagement in order to approximate the urgency and affect associated with living in the moment, or invisibilizing the experience of mediation altogether. But it doesn’t achieve this through discourse alone. The affordances of the app, from its home screen to its filters to its photo editing options further cultivate an aesthetic and functional grammar of ephemerality that often supports but sometimes challenges the dominant discursive construction of ephemerality. For instance, on March 31, 2017, Snap announced the addition of both an “Infinity” timer for Snaps, and Loops, a tool which allows a video to replay endlessly until it closes. Both of these new additions prolong the duration of engagement with a Snap. This move is one of many over the company’s five-year life span that seemingly reconfigure the boundaries of the ephemerality the app was founded on, and signal the flexibility of this construct, but also its reliance on the ability of the app to so seamlessly anticipate its users’ needs that such meditation seems to disappear. As the blog post states, “We’ve all felt the frustration of not being able to fully enjoy a Snap—even after replaying it,” suggesting that the discourse and functionality of ephemerality is co-constructed between Snap, Inc. and its users based on shared affective responses to the material constraints of ephemerality. The ephemeral toward which Snapchat aspires is not simply the disappearance of messages, but a social media experience in which mediation itself seems to disappear. It achieves this, I argue, through a polysemous construction developed in the company narrative, the materiality of the app, and the aesthetic affordances that attempt to approximate unmediated engagement and in so doing signal the horizon of social media experience.

Designing Disappearance

When the ephemeral app originally launched in July 2011, it was called Picaboo. The name evokes the ludic nature of the asymmetrical information game where one player has information that she reveals and obscures from the other in order to produce pleasurable effects. The Picaboo founders, Evan Spiegel, Bobby Murphy, and Reggie Brown, aimed to create a smartphone application that embraced the dynamic nature of everyday conversation by foregrounding the moments not polished enough for Facebook permanence or hashtag infamy. By the end of that summer, despite dreams of Instagram-style instant adoption, the app only had 127 users and Reggie Brown had left the company.9 The departure was acrimonious and Evan Spiegel and Bobby Murphy immediately changed the name of the app to Snapchat and started an aggressive word-of-mouth campaign that resulted in early adoption among young users drawn to the promise of disappearing data. By April of 2012 the company had 100,000 users.

But while disappearance was the draw, the founders framed that ephemerality as a form of freedom and authenticity not yet experienced in a digital environment. As Spiegel writes in the first company blog post on May 9, 2012: “Snapchat isn’t about capturing the traditional Kodak moment. It’s about communicating with the full range of human emotion—not just what appears to be pretty or perfect [sic].”10 In his first official company blog post, Spiegel surprisingly spends no time describing the app or its functions. The blog post instead focuses on what kind of an experience the app offers its users and describes a practice that embraces flaws and awkwardness rather than polish and poise. Spiegel mentions “perfection” and “beauty” twice in two paragraphs to highlight the ideal against which Snapchat strives. There is also no mention of either disappearance or ephemerality, but there is an intense focus on why people started using the platform and what kind of feeling the use of the app promotes. Snapchat promises users a freedom to be more themselves than they can be in other social media platforms.

In a September 20, 2013 company blog post titled “The Liquid Self,” researcher Nathan Jurgensen develops this idea further by contrasting the ethos of ephemerality with the albatross of the archive. “The logic of the profile,” he writes, “is that life should be captured, preserved, and put behind glass. It asks us to be collectors of our lives, to create a museum of our self.” The alternative to this permanence, he suggests, is the spontaneity and authenticity encouraged by Snapchat: “Rethinking permanence means rethinking this kind of social media profile, and it introduces the possibility of…something more living, fluid, and always changing.” Jurgensen’s definition evokes a phenomenological understanding of the relationship between identity and time as asserted by Henri Bergson: “Our personality shoots, grows and ripens without ceasing. Each of its moments is something new added to what was before.”11 In the Bergsonian framework the self does not transform from a static to an altered state as a result of experience, it is instead engaged in a state of constant transition as it compiles and incorporates perceptual information from external objects.

Fluidity and presentness is also a good way to describe the app because it has a much more decentralized structure than either Facebook or Twitter. Rather than opening onto a static “wall” or Newsfeed, from which you can navigate outward, Snapchat opens with an immediate camera view. The only navigational clues are a series of symbols that appear in white outline over the transparent background offering the camera view. Anchoring the symbols is the large white circle in the bottom of the screen: this is the “snap” button that captures an image. The “home page” is thus always different because it reflects whatever you—by way of your device—are seeing in the moment.

Beyond taking a photo, there are three options that appear on the bottom of the screen: Chat, Memories, and Stories. Chat allows you to send text messages, view other Snaps, and communicate directly with someone in your contact list. Memories allows you to access your Camera Roll to send Snaps and edit and access previously saved images and video. Stories links you to several primary features: Stories, Live Stories, and Discover. Stories are short compilation videos created and edited by individual users. Live Stories are also short compilation videos, but these are publicly accessible videos focused on a major location or event, such as an art festival, concert, or sporting event, to which a variety of users have submitted Snaps by tagging their contributions with that location. Snap then edits and compiles these contributions into a single short video that represents the event, a labor-intensive process still executed by a human team, instead of an algorithm. Inclusion is also highly competitive because a Live Story can receive as many as 20,000 submissions.12 This investment in human curation reflects the kind of attention and presence to Snaps that the app hopes to evoke from its users.

Like Live Stories, Discover is a narrative-driven content section, but it is sponsored rather than user-generated. Discover is a revealing section because it suggests other possible incentives for ephemerality than simply the “liquid self” ideal posited by Jurgensen. Discover content also disappears after 24 hours, and here ephemerality is a savvy economic bet because it creates a form of urgency not found in the archival model of networked sociality. In many ways, this is a familiar tactic. The dominant model of advertising for online content is “pay-per-click” (PPC), in which advertisers pay website owners only for the consumers who click on or through to their content.13 Examples include the pop-up ads that appear in the margins of a Facebook wall, or on the banner heading of a news story. The PPC model rewards distraction and has created an aesthetic of advertising meant to interrupt and draw away a user’s attention. The effect of these types of disruptive engagements, author Nicholas Carr argues, is that deep and linear forms of intellectual engagement, such as reading a complex and lengthy article, have fundamentally shifted with the expansion of the Internet. Our brains are being literally rewired to “take in and dole out information in short, disjointed, often overlapping bursts—the faster, the better.”14 Carr asserts that as patterns of thinking adapted to forms of reading on the Internet, companies responded in kind by catering more and more to the type of content consumption to which the contemporary brain has become accustomed.

Economists have likewise noted that this shift in cognitive patterns creates a new market, one that trades in attention as its primary currency.15 Michael Goldhaber argues that attention is the true commodity of Internet culture, one that “really is scarce, [because] the total amount per capita is strictly limited…[it] is a zero-sum game. What one person gets, someone else is denied.”16 Goldhaber rejects the “information economy” as a false construct because information is abundant, even prolific online, and thus has a lower value. Attention, on the other hand, is a limited and scarce resource that can’t be shared because we are biologically limited in this currency. Our brains can only spend a finite amount of time engaging with information. A new market has thus sprung up in response, one that attempts to capitalize on those fleeting moments of attention before they disappear.

Snapchat’s advertising model reflects an understanding of the demands of this market, while also commanding content that aligns with its overall aesthetic and design in order to more effectively compete for user attention. The Discover section of the app features content developed specifically for Snapchat from companies such as Refinery29, Buzzfeed, the NFL, and CNN. “This is not social media,” Team Snapchat declares in its January 27, 2015 blog post announcing Discover, instead it is “a new way to explore Stories from different editorial teams…Stories are at the core—there’s a beginning, middle, and end so that editors can put everything in order. Every edition is refreshed after 24 hours—because what’s news today is history tomorrow.” The blog post is deeply concerned with how time shapes narrative, but it also contends that too much time renders narrative meaningless. Discover looks similar in layout to Stories precisely because of this concentration on the temporal dimension of narrative. Discover is not meant to disrupt engagement, as PPC advertising does, it aims to seamlessly integrate with the platform interface, including its aesthetic and ethos of presence. This form of advertising is typically referred to as “brand engagement,” where companies focus on facilitating conversations and experiences across media platforms in order to develop a loyal customer relationship based on an emotional attachment.17 Because Discover content is also ephemeral, and included Stories are limited in number, what companies are paying for—nearly $50,000 for a 24 hour feature in the Discover section—is engagement with their braded content that mirrors the engagement with user-generated content.18 Discover was initially slow to take-off because advertisers didn’t yet understand the integrated editorial approach that Snapchat was demanding in order to align advertiser content with the overall ethos of the site. But the initial revenue stream Discover generated is no longer just a stream.19 CNBC reported in January that Snapchat advertising totaled $90 million in revenue for 2016.20 Although that number pales in comparison to the $1.7 billion of ad revenue that Facebook reported for 2016, spending on Snapchat is expected to grow to $935.46 million in 2017.21 Ephemerality, it seems, is big business.

Despite this new business model, however, the company pitches the Discover section as a return to a better way of life: “The best advertisements tell you more about stuff that actually interests you…we want to see if we can deliver an experience that is fun and informative, the way ads used to be, before they got creepy and targeted,” the October 17, 2014 blog post reads. Glossing over the fact that Snapchat advertising is startlingly personalized, the policy explanation appeals to the way that advertising feels rather than how it actually operates. Sarah Banet-Weiser reads this type of rhetorical move as aligned with a larger cultural shift toward a “brand culture,” in which companies “strive to cultivate relationships with consumers…that have at their core ‘authentic’ sentiments of affect, emotion, and trust.”22 Like the company’s very first blog post, which didn’t mention the functionality of the app at all in favor of a focus on its affective dimensions and rhetorical aims, the company blog post announcing the change also positions advertising as an affective dimension of the app, one that evokes both the past and the future. Because it is so seamlessly targeted to the metrics of your attention, it is thus an “experience” rather than a “sell.” And the policy can make that claim precisely because the content disappears, and fades in the user’s memory, making it feel unique and ephemeral, rather than targeted.

While the economic incentives of ephemerality are clear, the company also equates it with the kind of intimacy and privacy that is only afforded by selective communication that enjoys various levels of context. In a keynote address at the LA Hacks event posted to the company blog on April 13, 2014, CEO Evan Spiegel urged attendees to “build thoughtfully for our future generations that they may discover the joys of human relationship and individual expression, as protected by privacy.” Spiegel employs a familiar rhetoric that aligns individual freedom with privacy, a freedom that is under threat by archival modes of social networking. The alternative he proposes feels more private because it creates a context of intimacy and selectivity, much in the same way as the advertising on the app feels “less creepy” because it is integrated into the interface, and into the user’s experience rather than determined to interrupt and redefine it. Spiegel proposes that this form of expression “creates a space for us to make ourselves vulnerable,” and “allows us to share our deepest, most unique thoughts—thoughts that might be easily misunderstood in a different context.” Social media must, Spiegel asserts, create an environment of intimacy that creates a context of experience, rather than a demand for performance.

The context that Snapchat attempts to emulate is a cognitive one, that of memory. By allowing messages to be shared and then erased, the app attempts to simulate the experience of forgetting, ensuring the safe transfer and anticipated loss of intimate content. Like a secret whispered in the ear and imperfectly remembered later, the disappearance of the message suggests that we should engage with something in the moment, not in perpetuity. As policy researcher Viktor Mayer-Schöenberger notes, until only a few decades ago, “to remember was the exception; to forget, the default.”23 Similar to Nicholas Carr’s assertion that digital media practice is transforming cognition, Mayer-Schöenberger traces the externalization of memory through digital tools, and argues that such a shift is having more than an individual cognitive effect, it is transforming how we understand what it means to be social. The loss of forgetting is not simply about endangering a job interview or being forced to remember an embarrassing moment, as Snapchat’s first blog post playfully frames “the digital permanent record,” it is about losing our relationship to the alleviating interpersonal effects of a faulty memory.24 “Because biological forgetting is built into our human physiology, we never had to develop an alternative cognitive ability to correctly valuate events in our past,” Mayer-Schöenberger states.25 The danger of a digital memory is that a fight between friends that might have previously been forgotten can now be instantly recalled through email, chat, or social media, perhaps altering the current relationship between the friends. Mayer-Schöenberger terms this change the “curse of digital remembering,” and warns, “it goes much beyond the confines of shifts in information power, and to the heart of our ability as humans to act in time.”26 Previously, the passage of time would have lessened the sharpness and even the exact shape of the memory of a disagreement, allowing the friendship to move forward harmoniously in the context of the present, rather than the past. But now these friends are bound to the context of the past by the perfection of its capture. In his 2014 AXS Partner Summit Keynote published on January 27 on the company blog, Evan Spiegel echoes Mayer-Schöenberger’s wariness of this power of the past: “Snapchat says that we are not the sum of everything we have said or done or experienced or published—we are the result. We are who we are today, right now.” Both Spiegel and Mayer-Schöenberger emphasize that living in the present necessitates an ephemeral past because if it continues its uncanny reappearance, we become its prisoner.

The transformation of temporal context in archival social media is not merely a personal threat, Snapchat asserts, it is a legal threat as well. This juridical framing of the danger of the digital memory is something that is at the forefront of the “right to be forgotten” movement. Launched by a case from a Spanish citizen who argued that information about the years-old repossession of his home infringed upon his current right to privacy, this European test case proclaimed the right to privacy in the face of inhuman digital memory.27 Although this particular case was not upheld, the EU did later affirm that individuals have the right “under certain conditions…to ask search engines to remove links with personal information about them…where the information is inaccurate, inadequate, irrelevant or excessive.”28 As technology scholar Meg Leta-Jones explains, this movement is about more than simply removing records, “It is a larger cultural willingness to allow individuals to move beyond their personal pasts, a societal capacity to offer forgiveness, provide second chances, and recognize the value of reinvention.”29 The emotional context that ephemerality provides, Leta-Jones contends, is that of redemption. Forgiveness is forged by the promise of forgetting, a fundamental social construct.

Snapchat researcher Nathan Jurgensen frames it slightly differently in a July 19, 2013 company blog post: “the harm that permanent digital media can bring…is not evenly distributed. Those with non-normative identities or who are otherwise socially vulnerable have much more at stake being more likely to encounter the potential damages past data can cause by way of shaming and stigma.” Ephemerality, he argues, protects not only those harmed by the release of potentially damaging information, it also promises to minimize the risk of revelation through disappearance. What Leta-Jones and Jurgensen maintain is that the permanence of digital memory does not equally endanger everyone, but it does impose a universal and artificial standard to our relationships that is not desirable. This loss of forgetting becomes a loss of freedom in two ways: it encapsulates users in a past that can’t be escaped, and it prevents them from acting in the present. Thus, the loss of freedom is not simply a rhetorical move meant to align a product with an individual identity, as neoliberal “brand engagement” does. Snapchat instead declares that our relationship to time is a fundamental human right that has been altered by the permanent digital memory championed by archival social media. Changes to this standard, moreover, have the ability to restore a more just balance that provides users with the freedom to live in the present.

Archives and Security

Although the company changed its name from Picaboo to Snapchat in 2011, it did retain the original logo, an outlined ghost floating against a yellow backdrop. “Ghostface Chillah,” as he is affectionately called by employees and users, embodies much of what the company values, an experienced aura that cannot, ultimately, be raised to the level of material permanence. But the ghost is also telling of the company’s shadow values, its adherence to archives and data collections. The ghost is a spectral presence that haunts spaces, evoking histories and tensions not yet exorcised, but also not fully visible. The history and tension that is most significant to the app, on a material and rhetorical level, is the significance of the archive. The very functionality of the app is dependent on processes of retention and repetition, but these functions have also been built into the interface to provide users with a sense of security that true ephemerality seems to work against.

Ghostface Chillah is such an appropriate logo because it evokes the tension between persistence and disappearance built into the very materiality of the app. Snapchat runs on the Google Cloud Platform, a name that itself evokes ephemerality, but as Google reports, it has “built its cloud for the long haul.”30 This reliability is achieved by two key material processes. The first is redundancy, or the continuous back-up of data from the app to the multiple server farms that power Google’s Cloud Platform. The second is latency, or the amount of delay in rendering content on a mobile device. In order to reduce latency, Snapchat caches, or stores data on individual devices to increase the loading speed of the app. As the Privacy Policy notes, “We may also store some information locally on your device…as a local cache so that you can open the app and view content faster.” Creating an archive within both the device and the servers is what allows the app to function so rapidly and seamlessly. New media scholar Wendy Hui Kyong Chun has described these software processes as the “enduring ephemeral,” where the required processes of redundancy and latency, both fundamental protocols for cloud based applications, are engaged in a constant process of retention and destruction.31 Our data is involved in a constant cycle of being copied and purged. There is no such thing as a stable piece of data, it is always in flux, and thus vulnerable to destruction and transformation. The data protocol used by Google Cloud Platform is standard for most native to mobile applications, but for Snapchat this standard challenges their ephemeral narrative on a material level. While these procedures might not seem to affect how the user experiences the app, as Jacques Derrida has argued, “the technical structure of the archiving archive also determines the structure of the archivable content even in its very coming into existence…the archivization produces as much as it records the event.”32 Derrida was anticipating the changes to archives necessitated by the rise of digital technologies, and his assessment of the inevitable alterations in information in response to its intended retention is especially apt here. It suggests that the material demands of the app’s archive structure its modes of expression, however temporary they may appear. The back-end archival processing of Snapchat affects users on the front-end because it produces a controlling logic that can’t be escaped regardless of the design of the interface.

The necessity of retention is further articulated in the app’s perhaps less read Privacy Policy. As the January 10, 2017 update details, “Snapchat captures what it’s like to live in the moment. So in many cases the messages sent through our services are automatically deleted from our servers once we detect that they have been viewed or have expired…There are some exceptions though to this rule…” The stated exceptions make a distinction between “content” and “information” and outline different retention policies for each. Content is the message of the Snap itself, while information is the extensive metadata about that Snap, including, usage, location, device, phonebook, call log, camera and photos, and other data collected by third-party cookies. This metadata is collected on a regular basis, and is used in part for the analytics that allow advertisers to provide a “better, more intuitive, and satisfying experience,” as the company’s Cookie Policy states.33

But the company blog has also managed to equate that retention with a form of freedom it attributes to ephemerality. In a March 3, 2016 blog post CEO Evan Spiegel writes, “Over 100 million people use Snapchat every day because they feel free to have fun and express themselves. We take the security and privacy of all that self expression seriously.” In this post Spiegel is voicing support for Apple’s refusal to create a “backdoor” into the locked iPhone of San Bernardino shooter Syed Rizwan Farook, a move which ostensibly protects the freedom of individual users and private companies. But he also conflates two important ideas central to social media that can often themselves seem ephemeral and thus need unpacking.

First, Spiegel crafts the statement to reassure users that their information is private. This is important because a January 2014 breach revealed that hackers gained access to the personal information of nearly 4.6 million Snapchat users and posted it online. As the hackers later reported in an official statement the breach was intended to illustrate the company’s vulnerability in order to force Snapchat to increase security: “Our main goal is to raise public awareness on how reckless many Internet companies are with user information.”34 This perception of carelessness is significant because privacy, like the intimacy Evan Spiegel championed in his April 13, 2014 LA Hacks Keynote, is deeply dependent on context. If both parties don’t share the same view on privacy, it can’t be said to exist. As Epstein, et. al. describe it, privacy is “a discursive vessel filled with substance given a particular context and the strategic needs of the actors.”35 Those strategic needs aren’t always aligned on Snapchat and affect the construction of ephemerality because privacy and ephemerality have been so often elided on the site. In terms of functionality, the app privileges a closed network versus a public one, sharing messages from a contact list rather than through a public posting. And discursively, the company continues to reiterate this dynamic, such as in its November 1, 2015 blog post after a Privacy Policy update, stating, “the important point is that Snapchat is not—and never has been—stockpiling your private Snaps or Chats…we continue to delete them from our servers as soon as they’re read,” suggesting that such messages disappear. And yet, in the April 12, 2017 Privacy Policy, Snapchat reminds users, “the same common sense that applies to the Internet at large applies to Snapchat as well: Don’t send messages or share content that you wouldn’t want someone to save or share,” reminding users that the contexts of privacy on the site are dependent on an ephemerality that its can’t guarantee.

This complicated interpretation of a core company value is further illustrated in the second term Evan Spiegel raised in March 3, 2016 statement in support of Apple: security. In that statement he also equates data retention and distribution policies with a kind of national commitment to freedom via security. “Snapchat has zero regard for terrorists or any other criminals,” Spiegel asserts, “And we prove it by cooperating with law enforcement when we get lawful requests for assistance. In the first six months of 2015 alone, we processed more than 750 subpoenas, court orders, search warrants, and other legal requests.” This connection between security and ephemerality is not simply a material one, as Snapchat’s interface asserts, it is, fundamentally, an affective and interpersonal one. As political scientist Hans Günter Brauch notes, “‘security’ is…a process of interaction where social values and norms, collective identities and cultural traditions are essential…security is always intersubjective, or ‘security is what actors make of it.”36 As Brauch contends, security is itself ephemeral; it is a state of feeling that is never stable, or complete. Ephemerality and security thus express that which is now, including the affective weight of their own inevitable disappearance, requiring a perpetual intersubjective process of latency and redundancy. Neither is simply a state which an individual or a nation can achieve, it is instead a perpetual demand for data required to verify a feeling. And that is perhaps the strongest connection between these two affective states: while they are produced internally, they rely on externalities to make meaning.

What the focus on the concept of security makes clear is that disappearance evokes a sense of loss, even a loss of agency that the app tries to counter with practices and discourses of security that the company discursively posits as complimenting rather than corrupting the feeling of ephemerality. On the level of the interface, one of the biggest concessions to the archive was the introduction of the Memories function. “We realized that Snapchatters want to feel comfortable showing their Memories to friends while they’re hanging out together,” the July 6, 2016 blog post “Introducing Memories” reads. “It’s a personal collection of your favorite moments that lives below the Camera screen,” the post explains; the verb “live” again evokes the ghost mascot, suggesting that the memories are always sentient in the background, waiting to surface in the present. What sets Memories apart from the archival functions on other social media apps is that Memories is still an internal archive accessible only to the original user, rather than public archive accessible by others, and thus affords a sense of security. Memories promises to serve as a limited tool for personal recall because there is no publicly accessible archive that charts a Snap history, as you would find on a Facebook Newsfeed. But the Memories function still takes care to delineate the presentness of Snapchat through its design: “If you post a Snap you took more than a day ago…it will appear with a frame around it so that everyone knows it’s from the past.” Although the app is embracing the temporal multidimensionality of networked sociality by altering the interface to accommodate both past and present interactions, it still works to set the past apart by creating an internal visual grammar. Utilizing a white frame for older Snaps evokes the white borders of earlier paper photographs, and signals its archival nature rather than its present function. The past can serve a purpose in the present, the frame suggests, but only by providing context to the present, in setting itself apart. As WIRED writer Brian Barrett explains of the change, “A disappearing message is a fun gimmick, but some memories deserve more than that. In which case, why leave life’s milestones to Instagram?”37

The Ephemeral Experience

In a May 26, 2015 Code Conference interview, Evan Spiegel summed up his company in three short words: “camera, communication, content,” and when asked what Snapchat was ultimately creating, he replied, “entertainment.” The order of his word choice is significant because it emphasizes that the app is a tool first, a social media platform second, and an information channel last. The interface itself seems to be ordered along these lines, and is one of the aspects of using the app that people, particularly those over 25, find most disorienting, a fact that the company blog blithely ignores.38 “We…learned that conversation feels better when it’s visual. So we decided to make sure that every time you launch Snapchat we take you straight to the camera,” the May 1, 2014 post states. From this screen, navigation occurs with a series of swipes and gestures that allow a user to access the full range of tools and services. This design places an emphasis on both speed and affect, but it can also serve as a barrier to adoption precisely because it is so different from other social media platforms. But Snapchat’s popularity isn’t based simply on its photographic functionality. What engages users, and creates a unique visual grammar of ephemerality, are the ways in which Snapchat tools allow users to creatively manipulate their images to better express their presentness.

The first of these tools, Geofilters, was introduced on July 15, 2014 as “dynamic art for different places.” Geofilters are a variety of art frames that can be laid over photographs taken within a specific location. Because the Snapchat app can access a user’s location through the device, it quickly and accurately identifies the options available for Snaps taken in that location. Geofilters are broken down into two categories: Community and On-Demand. Community Geofilters are created by local artists and designers and are submitted to Snapchat for approval for longer-term use in a limited area such as a college campus or a city neighborhood. On-Demand Geofilters are filters designed by companies or individuals for use by Snappers within a specific location for a specific period of time. “Whether it’s for a house party or wedding, a coffee shop or campus-wide event, Geofilters make it easy for Snapchatters who are there to send your message to friends,” the Support page assures users. Like the rest of the Snapchat interface, Geofilters create urgency in the temporal duration, but they also impose a spatial limitation. On-Demand Geofilters are priced according to the length of time they will be active as well as how much space the filter will be applied to. Here ephemerality evokes both the present and presence through its limitations of the time and space of engagement.

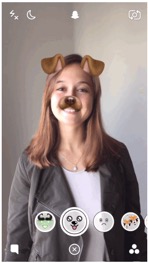

The second creative tool is Lenses, which create animated effects using facial enhancements and drawing tools laid over photographs. Lenses were introduced with the September 15, 2015 app update, and some of the most well-known filters include the rainbow vomit, and the face swap. Lenses can be accessed through a row of rotating buttons that appear at the bottom of the screen during the process of snapping a selfie. The alteration works by first mapping the user’s face with a geometric “mask” structure that pinpoints the borders of individual features in order to overlay the animated filters. The technology is surprisingly accurate, allowing users to switch Lenses quickly and seamlessly; one minute you’re a deer, and the next you’re a wizened old person. Once a Lens has been applied, the image can either be saved or sent to friends. Snapchat was able to integrate this functionality easily through its acquisition of the Ukrainian startup company Looksery, which was attempting to use its facial recognition software to start a new social networking platform.39

Filters are similar to Lenses, and work in much the same way, but differ slightly in that they can be applied to any image. Once an image has been captured, you can swipe left or right to overlay colored filters—similar to Instagram—that add the time, temperature or altitude, or even add a quick geolocational tag to any image, grounding it in a specific moment. Once you have taken any Snap, you also have the option to draw, write, or scribble on the photograph using your finger and the palette of colors provided under the pencil tool in the top right corner of the screen. Filters, more so than almost any other aspect of the app, evoke the archival nature of photography, what Roland Barthes refers to as the “that has been” quality of the photographic image.40 By overlaying an event filter you declare, “I was there, I lived this moment,” but always in the past tense. The moment of participation feels like a moment of presence, but the moment of circulation then becomes a moment of documentation, a move toward the archive.

The kind of interface integration offered by Filters and Lenses is also part of the overall engaged advertising model that Snapchat relies on for revenue. Companies can pay for sponsored Lenses at a rate of $350,00 to $650,000 for 24 hours, the most expensive ad purchase on the app.41 The most successful Lens to date was a 2016 Taco Bell placement that allowed users to turn their head into a giant Taco. The Lens was viewed more than 224 million times when it launched on May 5. And as Yum! Brands Chief Marketing Officer Marisa Thalberg characterized the campaign, “it was about creating a special moment for us on Cinco de Mayo.”42 Thalberg emphasizes both the intimacy of the ad—referring to the “us” of users and the company—and its temporality, the “moment” made special by the experience, which corresponds with Evan Spiegel’s repeated emphasis of Snapchat’s ability to capture the feeling of a particular moment.

Whether for corporate or creative purposes, Geofilters and Lenses are an excellent manifestation of how the ephemeral aesthetic is expressed as a material tension between disappearance and documentation. Drawing over a photograph to point to something ridiculous in the background, or adding an exaggerated effect to your face to show how beautiful, silly, or irreverent you are feeling allows users to create a unique and specific image. These effects are all added after the photograph has been taken, creating a longer period of time in which the photograph is suspended between the moment of its capture and the moment of its circulation. The emphasis on the manipulation of Snaps also evokes the malleability of the photographic image, its instability and impermanence on a material level that corresponds with the “enduring ephemeral” of the software that powers its capability. The ephemeral ethos does not simply mean that the photograph will disappear after a set period of time; Lenses and Geofilters suggest that a stable meaning of the “photograph” as either content or information never actually comes into existence. The image is instead an expression of the in between, a reflexive trace of a moment of creation that circulates as a durational experience.

The ability of the image to thus command a moment of attention within the app reinvigorates its scarcity rather than its multiplicity. Snapchat researcher Nathan Jurgensen highlights the deeply economic thinking that guides the design of the app’s photographic functionality. “Temporary photography by definition enforces a certain rarity,” he writes, “the meaning of the photo doesn’t rest just in its content but in the choice to restrict its consumption.”43 Returning to market metaphors, Jurgensen reads value as accruing within both scarcity and circulation, an ethos that is reiterated by the company narrative, and the app’s interface as much as by its advertising strategy. Scarcity, Jurgensen argues, is not a result of limited numbers, but of the limits on the time of consumption. It is not that more photos won’t be forthcoming, but that the moment of that exact photograph is finite. In his analysis of the legal ramifications of self-destructing data programs like Snapchat, Christopher Kotfila asserts that these systems tap into a consumer desire “to create disposable, short-term information [that is] slowly but surely re-introducing obscurity into an otherwise flat and persistent information landscape.”44 Kotfila’s notion of obscurity suggests that the image accrues value not simply because it is finite, but that such images, even in their abundance, have value because they are unique. Modification of the photographic image conveys that a durational engagement has been created just for you. Like the tailored brand engagement and the context afforded by privacy and memory, scarcity is a product of specificity.

What Ephemerality Means Now

On September 24, 2016, Snapchat announced a significant change; the company name has been changed to Snap Inc., and the logo has been multiplied. Now a single eye, a large black pupil surrounded by a white iris, floats in tandem with Ghostface Chillah. Under the new company focus, these two logos work together: “Snap Inc. is a camera company,” the new landing page of the company webpage announces. Gone is the emphasis on the platform, or even ephemerality. What remains is a vision of what ephemeral foundations might build, a reconception of social networking. “We believe that reinventing the camera represents our greatest opportunity to improve the way people live and communicate,” the announcement continues, asserting that not just social media, but society itself is in transition.

The company’s changed name and logo were announced on the same day that the company also announced the development of their newest product, Spectacles, which are sunglasses with an integrated camera that loads footage directly into the app under the Memories tool. “Imagine one of your favorite memories,” the announcement reads, “What if you could go back and see that memory the way you experienced it?” With Spectacles, the company is rhetorically reconceptualizing ephemerality; it is no longer about the disappearance of the archive, but about invisibilizing the apparatus that makes the archive possible. Whereas such functionality was once a procedural affordance of the platform, now the company has taken such a process one step further so that the decision to delete, or not, is a secondary decision. Storage becomes the default through the automatic capture and transfer of images via the livestream wireless camera. And yet, the company promises, “we won’t backup any photos or videos from your Camera Roll, unless you use one to make a new Story or add it to My Eyes Only. In that case we’ll back up only the photo or video that you used.” The statement plays with an affective attachment to time, both past, in the form of memories, and present, a feeling that those memories are actively integrated into the present. This is the aim of Spectacles, and by thus incorporating such a tool into a firmly established discursive structure, the company hopes their new product will enjoy a wider audience than Google Glass.45

“Our products empower people to express themselves, live in the moment, learn about the world, and have fun together,” the final paragraph of the new landing page description earnestly states. This ordering of processes suggests that by removing the apparatus of mediation, or at least embedding it in wearable technology, life itself will be seamlessly integrated into the social media framework. The ethos and aesthetic of the faulty ephemerality in Snapchat reimagines how time should be experienced in social media, and the design of the app expresses its affective dimensions, if not its material reality. As the rebranding statement from their blog communicates, social media is about presentness, about feeling as if one is living in the moment through the specific grammar of mediation the app provides. And other social media platforms are responding in kind by adopting the tools and language pioneered by Snapchat. On January 25, 2017 Facebook announced its newest product, Facebook Stories, which are photo and video narratives created by users that disappear after 24 hours.46

What ephemerality signifies, as the many changes to the app’s tools assert, is a fluid but powerful concept. But the surprisingly cohesive company narrative about how ephemerality feels asserts that users want to engage with social media differently, and that begins by letting go of static concepts about what platforms should be and do. Like the new unblinking eye logo, Snapchat appears to look clearly forward into the future of social networking. But perhaps what Snapchat’s flawed ephemerality signals most vividly is the transition to an experience of digital media focused on meaning and the disappearance of mediation. Scholars have looked beyond Web 2.0 and the focus on user generated content to characterize the next stage of Internet development as Web 3.0, which Tim Berners-Lee has called the “Semantic Web.”47 In this phase of Internet development, signaled by the Internet of Things (IoT) and improvements in artificial intelligence, we will be surrounded by an online environment that understands the content and context of data so that it seamlessly responds to and integrates within everyday life.48 This transition will essentially invisibilize the apparatus so that mediation itself becomes increasingly ephemeral. Within this larger framework of media history, Snapchat’s failures of ephemerality on a material level seem balanced by a prescient understanding of the complicated discursive role of ephemerality in the future of digital media practice.

Michael J. de la Merced, “Snap Shares Leap 44% in Debut as Investors Doubt Value Will Vanish,” The New York Times, 02 March 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/02/business/dealbook/snap-snapchat-ipo.html. ↩

Commentators have noted a parallel between Snapchat’s stock price dip and Facebook’s 60% drop in stock price four months after its IPO in 2012. Bilton, Nick, “Don’t Panic, Wall Street: Why You Shouldn’t Bet Against Snapchat and Evan Spiegel,” Vanity Fair Hive, 19 July 2017, http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2017/07/do-not-bet-against-snapchat-and-evan-spiegel. ↩

Sarah Frier, “Snapchat Passes Twitter in Daily Usage,” Bloomberg Technology, 2 June 2016, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-06-02/snapchat-passes-twitter-in-daily-usage. ↩

The 2015 Pew Research Center report “Teens, Social Media & Technology states that 41% of American teenagers between the ages of 13-17 are Snapchat users while a 2014 study by consulting film Frank M. Magid found that only 18% of all social media users are active on Snapchat. http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/09/teens-social-media-technology-2015/pi_2015-04-09_teensandtech_22/; https://www.emarketer.com/Article/Young-Users-Zoom-on-Instagram/1011795. ↩

Max Chafkin and Sarah Frier, “How Snapchat Built a Business by Confusing Olds,” Bloomberg Businessweek, 3 March 2016. ↩

See, for example: Andrew C. Billings, et. al., “Permanently Desiring the Temporary? Snapchat, Social Media, and the Shifting Motivations of Sports Fans,” Communication & Sport 5.1 (2017): 10-26; Joseph B. Bayer, et. al., “Sharing the Small Moments: Ephemeral Social Interaction on Snapchat,” Information, Communication & Society 19.7 (2016): 956-977; Lukasz Piwek, Adam Joinson, “’What Do They Snapchat About?’ Patterns of Use in Time-Limited Instant Messaging Service,” 54 (2016): 358-367. ↩

Sally Wyatt, “Danger! Metaphors at Work in Economics, Geophysiology, and the Internet,” Science, Technology, & Human Values 29.2 (2004): 244-245. ↩

Tarleton Gillespie, “The Politics of ‘Platforms,’” New Media & Society 12.3 (2010): 348. ↩

Alex Konrad, “Snapchat Billionaires Protect their Stakes by Settling with Ousted Cofounder Reggie Brown” Forbes 9 September 2014, http://www.forbes.com/sites/alexkonrad/2014/09/09/snapchat-settles-cofounder-lawsuit/#3312f9ac2123. ↩

Unless otherwise noted, I have retained all original spelling, grammar, and punctuation from the original Snapchat company blog posts. ↩

Henri Bergson, Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness, Translated by F.L. Pogson, (London: George Allen & Unwin , 1910), 175. ↩

Victor Luckerson, “How Snapchat Built its Most Addictive Feature,” Time Magazine, 25 September 2015, http://time.com/4049026/snapchat-live-stories/. ↩

Tracy Tuten, Advertising 2.0: Social Media Marketing in a Web 2.0 World (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2008), 6-9. ↩

Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2010), 6. Carr is citing Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994), 10. ↩

See, for example: The “attention economy” was initially outlined by Michael H. Goldhaber in a series of articles such as “Attention Shoppers!” WIRED 01 December 1997, https://www.wired.com/1997/12/es-attention/, and was then expanded in Thomas Davenport and John C. Beck The Attention Economy: Understanding the New Currency of Business (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2002), and its history and future implications have been recently explored in Tim Wu, The Attention Merchants: The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads (New York: Knopf, 2016); danah boyd, 6 January 2017, “Hacking the Attention Economy,” apophenia http://www.zephoria.org/thoughts/archives/2017/01/06/hacking-the-attention-economy.html. ↩

Goldhaber, “Attention Shoppers!,” WIRED 01 December 1997, https://www.wired.com/1997/12/es-attention/. ↩

Linda D. Hollebeek, “Demystifying Customer Brand Engagement: Exploring the Loyalty Nexus,” Journal of Marketing Management 27.7-8 (2010): 785-807. ↩

Garrett Sloane states in a January 14, 2015 Adweek article that the 24 hours cost of advertising on the site is $750,000, (http://www.adweek.com/news/technology/snapchat-asks-brands-750000-advertise-and-wont-budge-162359 ) but then reports in a June 29, 2016 Digiday article that the company dropped its rates to $50,000 for 24 hours in Discover (http://digiday.com/platforms/snapchat-slashing-ad-prices-brands-sources-say/), and Snap Inc. claims that it doesn’t comment to the press about advertising specifics. ↩

Tim Peterson, “See the Charts: Snapchat Discover is Averaging Just 2.5 Ads a Day,” AdvertisingAge, 12 August 2015, http://adage.com/article/media/snapchat-discover-averaged-ads-day-past-month/299929/. ↩

Arjun Kharpal, “Advertisers Spent $90 Million, Three Times What Was Expected, on Snapchat Last Year–and It’s a Threat to Facebook,” CNBC, 17 January 2017, http://www.cnbc.com/2017/01/17/snapchat-advertising-spend-by-clients-hit-90-million-in-2016-wpp-ceo-martin-sorrell.html. ↩

“Snapchat Ad Revenues to Reach Nearly $1 Billion Next Year,” eMarketer, 2 September 2016, https://www.emarketer.com/Article/Snapchat-Ad-Revenues-Reach-Nearly-1-Billion-Next-Year/1014437. ↩

Sarah Banet-Weiser, Authentic™: The Politics of Ambivalence in a Brand Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2012), 214. ↩

Viktor Mayer-Schöenberger, Delete: The Virtue of Forgetting in the Digital Age (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009), 92. ↩

The term “digital permanent record” was used by Matt Ivester, founder of the now defunct campus gossip site JuicyCampus to describe the impetus for the design of his site in his book, LOL…OMG!: What Every Student Needs to Know About Online Reputation Management, Digital Citizenship and Cyberbullying (Reno, NV: Serra Knight, 2011). ↩

Mayer-Schöenberger, Delete, 116. ↩

Mayer-Schöenberger, Delete, 117. ↩

Eleni Frantziou, “Further Developments in the Right to be Forgotten,” Human Rights Law Review 14.4 (2014): 761-777. ↩

European Commission, “Joint Statement on the Final Adoption of the New EU Rules for Personal Data Protection,” European Union Press Release, 14 April 2016, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_STATEMENT-16-1403_en.htm. ↩

Meg Leta-Jones, Ctrl+Z: The Right to Be Forgotten (New York: New York University Press, 2016), 11. ↩

“Future-Proof Infrastructure,” Google Cloud Platform, https://cloud.google.com/why-google/. ↩

Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Programmed Visions: Software and Memory (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2013), 137. ↩

Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, Translated by Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1995), 17. ↩

Kurt Wagner, “Snapchat’s Automated Ad Sales Have Arrived, And Real Ad Dollars Are Likely Coming Next,” Recode, 5 October 2016, http://www.recode.net/2016/10/5/13180176/snapchat-advertising-api-revenue. ↩

Nicole Perlroth and Jenna Wortham. “Snapchat Breach Exposes Weak Security.” The New York Times 2 January 2014, https://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/01/02/snapchat-breach-exposes-weak-security/. ↩

Dmitry Epstein, Merrill C. Roth and Eric P.S. Baumer, “It’s the Definition, Stupid! Framing of Online Privacy in the Internet Governance Forum Debates,” Journal of Information Policy 4 (2014): 149-150. ↩

Hans Günter Brauch, “Concepts of Security Threats, Challenges, Vulnerabilities and Risks,” in Coping with Global Environmental Change, Disasters and Security, Edited by Hans Günter Brauch et. al. (Berlin: Springer, 2011), 61-106. ↩

Brian Barrett, “Snapchat Saves Your Snaps Now Because Hey, Memories Can Be Nice,” WIRED 6 July 2016, https://www.wired.com/2016/07/snapchat-memories/. ↩

See, for example: Will Oremus, “Is Snapchat Really Confusing, or Am I Just Old?” Slate 29 January 2015, http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/technology/2015/01/snapchat_why_teens_favorite_app_makes_the_facebook_generation_feel_old.html; Kevin J. Ryan, “The Ingenious Reason Snapchat Makes Its App So Hard to Use,” Inc. 9 December 2016, http://www.inc.com/kevin-j-ryan/the-ingenious-reason-snapchat-makes-its-app-so-hard-to-use.html; Joanna Stern, “How to Use Snapchat,” The Wall Street Journal 12 January 2016, http://www.wsj.com/articles/snapchat-101-learn-to-love-the-worlds-most-confusing-social-network-1452628322. ↩

Josh Constine, “Snapchat Acquires Looksery to Power Its Animated Lenses,” TechCrunch 15 September 2015, https://techcrunch.com/2015/09/15/snapchat-looksery/. ↩

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, Translated by Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 75. ↩

Julia Boorstin, “How Snapchat Utilizes Lenses to Turn Users into Brand Evangelists,” CNBC, 26 August 2016, http://www.cnbc.com/2016/08/26/how-snapchat-utilizes-lenses-to-turn-users-into-brand-evangelists.html. ↩

Steven Perlberg, “Snapchat: How Brands Reach Millennials,” The Wall Street Journal, 22 June 2016. ↩

Nathan Jurgensen, “Pics and It Didn’t Happen,” The New Inquiry, 7 February 2013, http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/pics-and-it-didnt-happen/. ↩

Kotfila, “This Message Will Self-Destruct,” 15. ↩

Paresh Dave, “What Separates Snapchat Spectacles from Google Glass: Simplicity,” Los Angeles Times, 27 September 2016, http://www.latimes.com/business/technology/la-fi-tn-snapchat-spectacles-20160926-snap-story.html. ↩

Alex Heath, “Facebook Just Made a Key Move In Its Quest to Crush Snapchat,” Business Insider, 25 January 2017, http://www.businessinsider.com/facebook-testing-snapchat-clone-called-facebook-stories-2017-1. ↩

Tim Berners-Lee, James Hendler, and Ora Lassila. “The Semantic Web” Scientific American 284.5 (2001): 34-44. ↩

Matthew T. McCarthy, “The Semantic Web and Its Entanglements,” Science, Technology and Society 22.1 (2017). ↩