Alan Liu is known as a humanities scholar, but he might best be described as also an engineer of the humanities. He founded Voice of the Shuttle (VoS), the original web-based humanities index and search engine, and is the author of Wordsworth: The Sense of History (Stanford, 1989), The Laws of Cool: Knowledge Work and the Culture of Information (Chicago, 2004), and Local Transcendence: Essays on Postmodern Historicism and the Database (Chicago, 2008). Through all these projects he has engineered a series of enabling hacks on humanities methodologies that have changed the way scholars understand humanities research.

In his first book Liu set out to equip formalist and deconstructive reading strategies with a sense of history, making it possible to read Wordsworth’s denial of history as an important factor in his use of literary form. In The Laws of Cool, Liu devised a way to speak across the boundary between academia and business to ask whether knowledge of the humanities and arts has anything to contribute to the types of knowledge work whose primary mission is commerce. His recent work continues to seek a regenerated sense of history that can help us understand the peculiar sociality and historicity of databases and networks. Why? Because, he says, “we want a rich ecology of knowledge.”

Liu’s inquiries into the rich ecologies of digital networks puts the engineer back in touch with the humanist. This is a vital connection because it reminds us of the need to understand technical advances in terms of the historical agencies they channel. In our discussion for this issue of Amodern, Liu put it this way, “One of the key traits of humanistic work is that it relies on a vital historical understanding to drive, extend, shape, criticize its equally vital engagement with the present…. The ability to balance attention to the old and the new… is one of the unique features of humanistic work that should be put before the public as a humanistic contribution to society.” Which is to say that the humanities are important, as Marianne Moore once said of poetry, not because a high sounding interpretation can be put to them, but “because they are useful.”

The following exchange was conducted via email between Thunder Bay, Ontario and Santa Barbara, California.

—Scott Pound

It’s almost ten years since The Laws of Cool (2004) came out. How do you view this study of the fate of literary culture in the era of postindustrial “knowledge work” in light of the events that succeeded it: the great recession of 2007-09 and the subsequent upheavals within the University of California system where you teach?

When I started that book in the 1990s, I wanted to think about the fate of literary culture in the information age. But the project mutated. I discovered that my topic was the culture of knowledge generally in the age of “knowledge work.” I took “cool” to stand for the minimalist stub of culture that knowledge workers hold fast to amid the paradoxical privilege and plight of “lifelong learning” (lifelong insecurity under threat of managed corporate culture, obsolescence, restructuring, and outsourcing). As I put it: “We work here; but we’re cool.”

For the book, I used the year 2000 as a millennial marker of the dominance of knowledge work. Now, a decade later, it gives me little joy to say that the cool – e.g., students paying ever higher tuition while queuing for increasingly overenrolled classes, faculty who once did “theory” after the May 1968 protest era and now blog about “the cuts,” and, outside the academy, every other knowledge worker who lost ground to the “1 percent” in the great recession – are even less cool than they once minimally were. In particular, it pains me to see how completely of its moment (not ahead of its moment, because the great recession only surfaced ongoing trends) The Laws of Cool was in passages like this:

[T]he build-up to “2000” [has not] been merely a remote abstraction for academics. As indicated by controversies in the late 1990s over plans to “partner” the information systems of major U.S. universities with technology corporations, to restructure other universities according to the philosophy (declared by one university president) of “pretending” to be “a corporation,” to gear still others for the technological future by eliminating whole suites of liberal arts programs, or, in New Zealand, to reorganize the higher education system into strictly “accountable” corporate units, the academy is increasingly being told by administrators and legislators to attend to business, or else.

It pains me in particular because I’ve now gotten a close up and personal look at this dystopian scenario. While in the last decade I’ve continued to teach, research, and write, arguably the roles that have most absorbed me were academic versions of what business calls “middle management” and “tiger teams.” “Middle management” refers to being a department chair in the University of California system from 2008 to 2012, just in time for instructor cutbacks, faculty and staff furloughs, talk about an all-digital “eleventh UC campus,” and (in my campus’s humanities and arts division) a restructuring that took away department staff and centralized them in multi-department clusters. “Tiger team” (fangless though we were) refers to being team leader of one of the subunits of the Research Strategies group that (along with several other such groups) supported the work of the UC Commission on the Future (UCOF). The UCOF was launched by the UC Regents in 2009 with the mission, essentially, of imagining a future for our public university eviscerated of both public funding and public moral support.

I learned in that period in gritty detail how the great recession is forcing higher education, especially public institutions, fully into the age of knowledge work. It’s too easy to blame individual legislators and administrators who want to make higher education imitate the business of knowledge in the private sector. They’re only channeling a structural change. Earlier in this long cycle of change, Bill Readings in his University in Ruins had decried the transformation of knowledge into “excellent knowledge,” which for him was an ironic term (like Lyotard’s “performative knowledge”) meaning merely efficient, systemically aligned, and technically proficient knowledge work. I fear that the great recession has made even this too high a goal. Now we are in the age of good enough knowledge, where the metrics will all be tuition levels, enrollments, graduation rates, numbers of MOOC registrants, partnerships with businesses and foreign universities, and so on. If we can just get the metrics right, then perhaps higher ed will be good enough to give students the fragile illusion of access and opportunity even as they see their parents laid off, underemployed, stripped of pensions, thrown out of safety nets, and pilloried for wanting bargaining rights won during a previous century of even more naked aggression on the people who once literally “mined” and “harvested” but now data mine and harvest.

The critical stance I took toward all this in Laws of Cool is a double one that I still take, and even more so. On the one hand, the effect of the great recession on the academy prompts me, and many others, to react against what I am now calling the cultural singularity. The cultural singularity is when, as I said in Laws of Cool (though I did not use the phrase then), “competing models of knowledge work, once rooted semi-autonomously in academic, business, media, health-industry, government, and other sectors” fuse “into a single, parsimonious continuum – so-called ‘worldwide’ – able to afford just one global understanding of understanding.” I continued, “Wherever the academy looks in the new millennium, it sees the prospect of a world given over to one knowledge—a single, dominant mode of knowledge associated with the information economy and apparently destined to make all other knowledges, especially all historical knowledges, obsolete. Knowledge work harnessed to information technology will now be the sum of all worthwhile knowledge.” I think that one of the appropriate missions for academics now – and especially humanists, artists, social scientists, and basic-research scientists in the academy whose work cannot be measured by numbers of patents or results in the nearest economic quarter – is to make the case that society is stronger for having multiple different institutional, organization, and professional domains. We want a rich ecology of knowledge, not a monospecies domain, like .com.

But, on the other hand, I think that so many of us in the academy who protest “the cuts,” “privatization,” “corporatization,” “neoliberalism,” and so on are stuck in a last-century, industrial-age mode of reaction based on a now false binary of big business versus us. It feels good to march, literally or figuratively, against privatization–especially when prompted by such immediate issues as furloughs, closures of humanities programs, etc., as opposed to long term structural problems. What goes unrecognized in such protest is the fact that it’s not a clear binary. While business today has some awful ideas, it also has some powerful, insightful, and forward-looking ideas about “knowledge” and how to train for work in knowledge. After all, future-oriented information tech businesses like Google or Apple no longer have corporate “headquarters” but corporate “campuses.” They have imitated, assimilated, mutated, extended, exploited, experimented with–not sure what the right verb is, maybe all of them–the higher education model. I thus still stand by this statement in Laws of Cool, which is self-critical of academics in the service of a better grounded criticism of privatization:

Only if scholars now think about business as an intellectual and practical partner in knowledge work, therefore, can the critical issues in the relation of the academy to business be joined. Asking business for nice work need not mean selling out, but only if the contemporary academy engages business in a full act of critique in which it both gives and takes. Such reciprocal critique cannot even be initiated unless it is elevated to the proper level, where scholars first assume that the academy and business have a common stake in the work of knowledge and, second, ask, “What then is the difference?” What is the postindustrial, and not nineteenth-century, difference between the academy and the “learning organization”?

I would thus like the academy to start on the premise that we have something to learn from privatization, just as privatization has something to learn from us. Then what? is the logical next question. What is it that the academy additionally and differentially adds to the rich ecology? I’d like higher education to be able to say that today there are many partners in the process of preparing people for and employing them in knowledge work, and that society gains something from having not just business paradigms involved but also educational paradigms that are strategically different in core ways suited to today’s needs.

What you say here reminds me of Bruno Latour’s distinction between critique and what he calls “compositionism.”

With critique, you may debunk, reveal, unveil, but only as long as you establish, through this process of creative destruction, a privileged access to the world of reality behind the veils of appearances. Critique, in other words, has all the limits of utopia: it relies on the certainty of the world beyond this world. By contrast, for compositionism, there is no world of beyond. It is all about immanence.

Your work is a consistently strong affirmation of the critical stance but with an equally strong push in the direction of immanence (reciprocity, partnership, etc.). How meaningful is this distinction to you and what’s your reaction to Latour’s contention that “critique has run out of steam”?

Latour’s essay is of a piece with the parts of French theory that I ultimately enjoy the most – the parts that cherish the contingent, ad hoc, ephemeral, and local. “Compositionism” has the same feel as Jean-Luc Nancy writing about the “infinite finitude” of mortality (“Infinite History”) or of other French theorists writing about the tactical, micropolitical, bricolage, differénce, the rhizomatic, and so on. Ironically, from the viewpoint of a lapsed Romanticist such as myself, much of this thought feels like a very tardy, post-French-Revolutionary (not just post-May-1968) French reinvention of British Burkeanism (though unshackled of the empiricism that was the other part of that legacy). It’s an atonement for past seasons of universalist, absolutist, and we-want-revolution-now critiques that today votes with the opposite party: the party of the slow, piecemeal, common-law, always settling and never settled, picturesque, and possibly at last romantic organicism of aggregative common culture. Compositionism is the theory of, and as, compost heap (sort of like John Constable’s deeply-observed devotion to that messy, crumbly dung hill in his Stour Valley and Dedham Vale). Hence passages like this in the Latour essay (which later finishes with his signature homage to a pre- or postmodern “kakosmic,” messy, unsettled, and animated “nature”):

From universalism [compositionism] takes up the task of building a common world; from relativism, the certainty that this common world has to be built from utterly heterogeneous parts that will never make a whole, but at best a fragile, revisable, and diverse composite material.

Make that “compost material.”

So I would say that the parts of my work that call for self-criticism as much as criticism, learning from other social sectors (even business) as much as from the humanities and arts, and acceptance of complicities with as much as critique of dominant cultural forces are in agreement with Latour. Pure critique is just a sharp guillotine. Equally, neoliberal “creative destruction” and “disruption” – as ideologized by management gurus or politicians and administrators acting as sock puppets of such gurus – is pure critique from the other side. Neither purity can achieve the plurality needed for a workable plan, whether a business plan or a plan for civilization. What I take away from Latour, therefore (if you will let me to stay with my compost or dung trope a moment longer) is this: critique can’t just be a matter of calling the other side shits and their positions garbage. Some of their shit and garbage mixed with ours would make good compost.

However, I can’t agree entirely with Latour’s drift of thought, which ultimately strikes me as taking too universalist or absolutist a meta-critical position on the difference between critique and compositionism. It doesn’t take very long in his essay for that extremism to emerge. Take a look at this passage, for example:

[W]hat performs a critique cannot also compose. It is really a mundane question of having the right tools for the right job. With a hammer (or a sledge hammer) in hand you can do a lot of things: break down walls, destroy idols, ridicule prejudices, but you cannot repair, take care, assemble, reassemble, stitch together. It is no more possible to compose with the paraphernalia of critique than it is to cook with a seesaw. Its limitations are greater still, for the hammer of critique can only prevail if, behind the slowly dismantled wall of appearances, is finally revealed the netherworld of reality. But when there is nothing real to be seen behind this destroyed wall, critique suddenly looks like another call to nihilism. What is the use of poking holes in delusions, if nothing more true is revealed beneath?

This is a small point, but I think it is representative: what has Latour got against the hammer? There is something excessive in his meta-critique of the hammer of critique. I’m not a carpenter, but I’ve used hand tools enough to know that hammers in fact do also put things together. That’s the idea of a nail, isn’t it? Maybe it’s because I’m the son of a structural engineer and descended from a whole clan who were allowed to immigrate to the U.S. because they were engineers and builders. But how do you think the walls got put up in the first place (by people using hammers) before then being broken down again (by people using the same hammers)? Of course, different tools have different affordances, but even the guillotine – which I alluded to earlier – had its constructive side. As proposed by the French physician whose name it bears, it was intended as an instrument for the progressive reform of capital punishment. Indeed, the six propositions that Dr. Guillotine put before the National Assembly in 1789 are quite surprising when we look back at them because they include a supernumerary social-justice argument: not just advocacy for the equal, standard punishment of criminals but also advocacy for the just treatment of family members of criminals (Article 3: “The punishment of the guilty party shall not bring discredit upon or discrimination against his family”; Article 4: “No one shall reproach a citizen with any punishment imposed on one of his relatives. Such offenders shall be publicly reprimanded by a judge”). The guillotine was a platform both for destroying and for “composing.” It was by design a composite instrument (though, of course, it also quickly became composited with alternate motives in its tactical use and public perception).

So the more I think about it now, the more I come around to the view that the decisive issue is how we relate critique to what Latour calls compositionism. I’m not for positioning one against the other in an oppositional binary, which would itself be a meta-act of puritanical critique. Indeed, it may be that there has never been such a thing as critique that is not also compositionism. Nor do I think it is any longer useful to describe the relation between the two as “dialectical” or “synthetic.” We have played out that mine for the time being. Even “partnership” or “collaboration” don’t quite seem right, since such vocabulary participates in the discourse of the duopoly formed by the ideologies of economic neoliberalism and “open-source” knowledge work (strange, phase-shifted versions of each other). For lack of a better idea at present, I would settle for framing the relation between critique and compositionism according to the root idea of revolution: as a circling or cycling. Critique and compositionism are best understood as arcs in a common cycle of thought, whether at the level of individual projects or of longer generational agendas. Think of it this way: in any project there are tactically important moments when critique is constructive, e.g., at the beginning when assessing what is wrong with precedents or in the middle after the first prototype. Equally, there are tactically shrewd moments when composited methods and viewpoints are constructive, e.g., when the architect pitches a project to a client and has to incorporate the client’s views, when the architect then has to adjust plans in response to the structural engineer, and when the engineer subsequently has to adjust plans in response to the contractors, not to mention the tactically decisive construction workers who actually wield the hammers). It’s just that neither critique nor compositionism has a right to rule as the “last word” in the process–the terminal stage, the end result, the payoff, the final record. In the humanities, I feel, we have fallen into the rut of thinking that interpretive discourse (e.g., a critical essay) should be the final statement of a project, and, further, that critique should be the final payoff of interpretation. But what if we were to position interpretive discourse and critique elsewhere in the cycle of thought that goes into a project? Compositionism would then not be antithetical to critique; it would include the arc of critique, and vice versa, as part of the rolling launch of thought. The same at the generational scale. It’s not that critique became empty and nihilist forever after the French Revolution, or again after May 1968, or yet again recently after the “occupy” response to the Great Recession. It’s that critique comes and goes in the cycle of the collective project, to be recalled for service by a new generation in a new moment of need. (By the way, this is similar to my view about the current “hack vs. yack” or “do you have to be a builder?” controversy in the digital humanities field where I spend a lot of my time now. This artificial controversy assumes that either hacking or yacking has to be the be-all and end-all rather than an ensemble player in a reiterative, episodic dramatic cycle. But that’s another debate.)

In the praxis of the UC crisis I mentioned earlier, this all crystalizes in my experience linking up with faculty members from other disciplines in the Research Strategies working group of the UC Commission on the Future. As one of its designated humanities representatives, I came into that forum, which was charged with strategizing the future of UC research in a time of zero-sum resource battles, in a partisan critical posture. I was set on defending the humanities against the continuing ascendance of the STEM sciences. But I came away with a deeply compositionist appreciation of how the humanities are actually in many ways in common cause with the STEM fields – e.g., with the scientists I worked with who felt passionately that their “basic research” was threatened by the same myopia about applied technologies and marketable results that is eclipsing the humanities and arts. Not only that, when I worked alongside one of UC’s agricultural scientists and learned of the deep investment he and his programs had in our land-grant system’s historically-deep tradition of public service as well as his program’s innovations on that tradition, I felt keenly by contrast that the humanities typically put little practical, let alone programmatic, thought into how they can be of service today. Among other things, compositionism is humble pie.

That’s true. When Pound says to Whitman, “Let there be commerce between us,” there is a large helping of humble pie being eaten. You’ve said that humanists need to put their minds to how they can be of service and how they represent themselves to the public. What new methods and formats and forms of instrumentality do you see emerging that might help them do that?

I’ve been giving talks on this topic for the 4Humanities initiative. I have favorite ideas for new forms of instrumentality, as you put it–especially ones that take advantage of today’s networked technologies and also set a direction for how we might develop a future generation of such technologies. Beyond instrumentalities, I also have ideas about embedding public engagement in the training and ordinary work of humanities scholars.But before creating a spec list, as if we were immediately starting an engineering project, it helps to look at the larger picture. Here are three factors that I think lie in the background of the current need for the humanities to re-present themselves to the public.

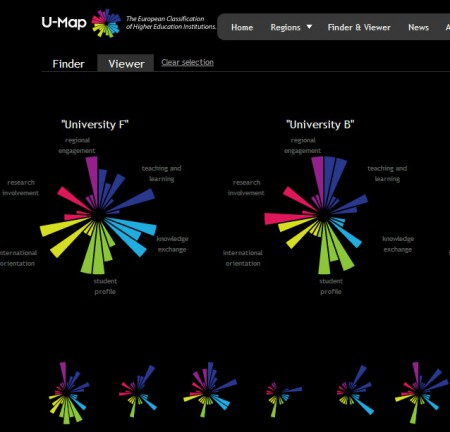

First, the disconnect between the academic humanities and society, whether we think in terms of public understanding of, or public support for, what we do, has been growing over a long period – at least since the advent of the “two cultures” schism. So it isn’t only a case of the humanities (with the arts and social sciences) needing to defend themselves in immediate response to the latest economic recession; the latest dismissals of their value by politicians, university administrators, and media pundits; or the latest calls for neoliberal privatization and accountability. Of course, we do need timely humanities defenses in the face of all that, since otherwise the only way the public will see the humanities from now on will be as a kind of eclipse in the frightening sunburst chart tool for university accountability that Australia is considering implementing, the European U-Map tool that helped inspire it, or the Obama White House’s new affordability and transparency College Scorecard. In the world view fashioned by such accountability tools, the humanities will always be a minima to the STEM fields’ maxima. For example, what would the metrics for royalties, patents, funds from industry, and so on for the humanities look like in the purple sector of the Australian sunburst charts? But reacting to immediate urgencies is the battle, not the war. Engaging, or reengaging, the public to make a persuasive case for the value of the humanities will need to be a long campaign over many generations – a far longer time horizon than the longest typical time line for activism in the contemporary humanities (going back to May 1968).

Second, I say “reengaging” in the sentence above because the issue of how the humanities should present themselves to society is part of a broader theme today: the great change in how institutional expertise of many kinds (e.g., in higher education, cultural or heritage institutions, journalism, government) engage with the new public networked knowledge (exemplified by Wikipedia or the blogosphere). There is no longer a one way flow in which experts send their knowledge to the public (mediated by journalism and other agencies) while the public sends back only mute feedback in the form of tax dollars, tuition, subscriptions, membership fees, and so on. The flow is increasingly bidirectional or multidirectional. Presenting the humanities afresh to the public today will mean helping to create the new institutional structures, practices, incentives, discourses, and technologies needed for reinventing the role of expertise in the world. “Reengagement,” then, in the sense of reinventing engagement. What would it take, for instance, for humanities scholars to post Tweets or contribute to Wikipedia in a way that advances both their own careers and the public interest? To put it mildly, it would take a lot. There would need to be many changes behind the scenes in the academy and the profession, spanning from revising promotion review procedures (e.g., to evaluate collaboration with professional-amateur “pro-am” members of the public) to rethinking the lifecycle and even underlying epistemology of academic “research” (e.g., so that we might break out our normal, preparatory “literature reviews” and “environmental scans” as modules to be contributed to Wikipedia in compliance with its “no original research” rule).

Third, the STEM sciences have a track record in producing publicity materials that put their accomplishments before the public. I admire the glossy posters, brochures, and online sites I have seen produced by national laboratories that showcase how STEM contributes inventions, medicines, and so on–all of which supports not only the thesis that applied science is valuable but the subthesis that basic research is even more fundamentally valuable. An example is the “breakthroughs” Web site of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which displays not only research with obvious application but also the literally elementary value of basic research (“discovered sixteen elements”). By contrast, the academic humanities not only do not have a robust tradition of showcasing what they do to the public, but they also almost never have the resources to devote staff and expertise to producing such materials. Beyond ad hoc publicity for lectures and events (supplemented by occasional campus news releases), it’s DIY.

So, if you add up the above background factors (and likely many more that could be mentioned), the picture comes clear. If humanists are to make a convincing case today and in the long term that they serve the public and so deserve public support, they will need to do more, when whacked by budget cuts, than pop up like moles in one hole after another, asserting “me, me!” – where the “holes” in this (admittedly wacky) whack-a-mole allegory of mine are the typical arguments legitimating the humanist “me” that the public sees just as voids sinking down into some impenetrable, hermetic labyrinth of academese. (Every time I explain to non-academics that I train students in “critical thinking,” “close reading,” “humanistic values,” “historical understanding,” etc., I see their eyes glaze over, and I know that I am lost in translation.) Humanists will also need innovative and sustainable public reengagement strategies–ones that innovate for the present moment of changing relations between expertise and society and ones that can also be sustained for the long haul with normal humanities staffing, energy, and time.

So my spec sheet is as follows, starting with instrumentalities. We ought to begin by designing humanities advocacy campaigns (whether for individual projects, departments or programs, institutions, or the humanities generally) that do the following. (a) Identify core humanities values. This is a non-trivial exercise. Most humanists, myself included, merely assume they “know” the value of what they do in some deeply ingrained way. But we don’t really know that value (or values) until we know how to tell it to others. Indeed, the very process of trying to tell others is likely to prompt new knowledge about what we thought we knew. So an initial step is self-study, not just through our usual methods of reading groups, colloquia, etc., but also through new study formats (e.g., design charrettes, ethnographic observation of our daily and nightly work) as well new data-mining, visualization, crowdsourcing, and collaboration technologies that can help us set aside our preconceptions to identify what our values actually are and also what others in society think they are. For example, 4Humanities has done some trial text-mining of pro and con statements in the media about the humanities; and we’ve also done some trial crowdsourcing to harvest arguments for the humanities. We’ve also started a new project called WhatEveryISays to collect and text-analyze a corpus of public statements about the humanities. (b) “Frame” our values in effective narratives, metaphors, evidence, and visuals. My local chapter of 4Humanities at UCSB has been using “frame” theory à la George Lakoff and others, and also in the manner of the Frameworks Institute, to think about how to reframe discourse about the humanities. You can see one product of that in the piece I wrote for the 4Humanities “Humanities Plain & Simple” initiative on “The Humanities and Tomorrow’s Discoveries.” There, I reframe the discourse of STEM “inventions,” “innovations,” and “breakthroughs” in terms of a more expansive concept of “discovery” in which the humanities have an integral role. (c) Put our values and “frames” before the public through older print and broadcast media blended with current digital media. This will require a judicious repertory of spokespeople (not necessarily academics or humanists) and a well-designed mix of old/new media channels and genres, linked up as appropriate to specific causes and events in their local, regional, national, or international milieux. (d) Finally, build a future generation of digital technologies that can embed public reengagement in the ordinary work of humanists. The idea is that public reengagement shouldn’t be something that humanists or their department do in what I call the 25th hour – the mythical, wished for extra hour of each day after all we’re done teaching, grading, sitting in committees, parenting, and so on. It should flow organically out of what we already do.

So imagine something like this. First imagine that the ordinary word processing and other tools we use to produce research notes, lesson plans, course syllabi, publications, etc. are linked to DH tools (e.g., for text-analysis, topic modeling, social network modeling, visualization), all chained together in such a way as to generate “raw” machine-harvested digests, summaries, contexts of related work, etc. All of that would certainly be too rough to present “as is” to the public; nor is it clear that we would want to present it all. But the material would be ready for relatively rapid human selection, curation, and adaptation (by ourselves or delegates) if and when we decided to put up a Web page, blog post, Twitter post, RSS feed, etc. (perhaps in a changing exhibition space on our department’s home page, with parallel streams to our personal online sites and also to national or international aggregator sites). Secondly, imagine that another set of tools are expressly designed to help us manage the publication, promotion, and circulation of such materials (e.g., through search engine optimization, cross-posting, submission to the aggregating sites mentioned above, and modularization for social media such as Twitter). Finally, imagine that yet another set of tools helps us solicit and harvest public feedback, crowdsourced knowledge, and crowdfunding. The basic idea is that we ought to equip the humanities – whether individual scholars or programs – with the means for generating from their normal workflow an accompanying wave of public materials and public message streams. We want to expose to public view – in process as well as after the fact – some of the actual living stuff of what we do: our discoveries, our ideas, our best classroom questions, our best student projects, and, as it were, our best doubts and weaknesses as well, the existential and practical ones that show us to be thoughtful participants in, and not just commentators on, the shared human drama. For me, this would be the fullest meaning of “open access.” I know there are plenty of problems with this imagined scenario, including intellectual property issues, privacy issues, human subjects research protocols, obstreperous or overly influential members of the public, mismatches between expert and public discourse, etc. But these are problems that we should look forward to exploring. We now live in a technological age that allows us to break out of the silo of the academy and be seen to live and work in public, with the public, and for the public.

Which leads me to the human side of the equation: the fundamental nature of our training and work as humanists. It all needs to be refreshed with public reengagement. Consider the analogy (even if not exactly right) of engineering programs that offer their students courses and workshops in making a business plan or presenting research to venture capitalists. I had always thought of that approach as too vocational – verging on mercenary, entrepreneurial, and neoliberal – for the humanities. But I had a wake-up moment during my service on the Research Strategies working group for the UC Commission on the Future. A STEM-field graduate student in the group made an eloquent plea for us to consider recommending that future graduate education include training and experience in public engagement, where engagement was framed in expansive and service-oriented ways. I thought to myself: how shameful that this came from a STEM student and not a humanities faculty member. More than “shame on us,” there is self-interest for us as humanists in such an approach. I thought: I know so many humanities graduate students who are not only passionate about public issues but build that passion into their research topics. After all, that is where much of cultural criticism; race, ethnic, and gender studies; postcolonial studies; and now anti-neoliberalist studies, as well as other vibrant movements, come from, not to mention all our “theoretical” allegories (e.g., “rhizomatics”) mirroring our drive (at least as expressed in its modern Western form, with allowance for alternative understandings of the pursuit of happiness elsewhere) for human emancipation and equality. The self-interest of the humanities, I thought, would be served by creating a training path – not just courses or informal colloquia, but perhaps also extramural internship and other opportunities – for our best, brightest, and most passionate students to act on their activism in a way that blends formal education and public engagement. And, of course, such self-interest is also the public interest – an ideal blend that would be the humanist version of what the most idealistic yet self-interested Silicon Valley start-ups avow. They’re all about entrepreneurship that can “change the world.” I’d like the humanities to create a pathway that adds a “change the world” item on the agenda next to “get a Ph.D.,” “get a tenure-track position,” “get a lectureship,” and “publish a monograph.” At a minimum, that might lead to more avenues for our students to explore in the job market. Of course, there is no certainty that including public humanities, public communications and media, internships, community service, etc. in humanities training will result in more jobs. But the humanities owe it to their students to try some experiments.

In the end, it may all come down to that loaded word in your question: “instrumentality.” What do we in the humanities think instrumentality can be? Instruments in the age of science and industry, especially as refashioned into the digital technologies that are the neoliberal “mode of development” (Manuel Castells’ term), are supposedly all about industrial efficiency updated for postindustrial flexibility. Ultimately, such instrumentality is the very image of extreme late capitalism – i.e., of capital regulated by no more than the technical constraints of digital networks to flow in and out of investments at the speed of greed without any holdfast commitments to material and human resources. It’s all dollars and bits. But the humanities have their own rich, deep, full-throated tradition of instrumentality, originating in a far past when higher education had not yet divided from religious institutions – or, rather, when there was a mix of older institutions and newer polytechnic and other institutions. I am myself a stranger to religion. (I was born in a family in which I basically never heard of religion until I arrived as a child immigrant in the U.S., where learning that people believed in religions was a little like an anthropological study. Let’s leave aside here possible motives for why I became a Romanticist in my early professional career.) But we don’t need to be religious to know that the humanities have a deep relation to the humanistic version of a mission, which is service to humanity. Service is the instrumentalism of the humanities. If today’s neoliberal informationalism runs on client-server data architectures, then it’s the mission of the humanities to renovate, expand, and humanize the idea of service buried latently in the servers of neoliberalism. The purpose of those servers is to serve human beings, not “clients.” If the humanities are increasingly proletariatized in “service” positions in universities, where their faculty do more teaching, etc., then their long-term mission should be to convert a position of weakness to one of strength by growing both the academic and public awareness of the capabilities, range, and status of service until it seems a fundamental function of all expert activity – one in which the humanities can not only be a partner but, as befits any true partner, a leader when called upon.

Okay, I’d better step down from my soapbox. None of this is to say that every humanist needs to do advocacy, or that we shouldn’t concentrate on what we do best (our research and teaching) and also what is simply most zestful. I’m all for that, since we would be untrue to ourselves otherwise. It’s just that only doing what we do best with the most zest isn’t getting the job done anymore, meaning (at the most practical level) being convincing about why we – and especially our students and also adjunct colleagues going forward – should have good jobs.

The last mile in such a project of reengagement might be the task of connecting the historical consciousness/conscience of humanists with the presentism of network culture. But as you have often pointed out, networks have their own histories and their own humanities too. Perhaps you can talk about the concept of “network archaeology” and what it brings to a humanist understanding of network culture.

I think it’s important that you make a bridge to network archaeology from the idea of historical understanding. It’s worth pausing on that older idea for a moment because it’s a key part of humanistic understanding that needs to be carried on, even if in a thoroughly reshaped way, via the “archaeology” approach in media studies. Most of my career has been spent working on one part or another of what I am now calling the “media, history” problem, where the comma in the phrase indicates both a conjunction and an aporia. With varying emphases on one side or other of that comma, I’ve thought about “media, history” in my books Wordsworth: The Sense of History, Laws of Cool, and Local Transcendence (e.g., the last chapter on “Escaping History”), and also in essays like “Imagining the New Media Encounter” (2007) and “Friending the Past: The Sense of History and Social Computing” (New Literary History 42.1 [2011]).In fact, let me take a page from “Friending the Past” to set up for saying something about network archaeology. In that essay, I compared the sense of history in the late 18th and 19th centuries to the sense of sociality that characterizes Web 2.0 today. The former (especially as narrated by the great writers of historicism, e.g., Leopold von Ranke) served as a foundation for Western cultural self-understanding then; and the latter (especially in its reified form as “the social graph”) serves as a similar foundation for cultural self-understanding now. Both have an overdetermined relation to the ideology of democratic sociality. Rooted in the age of revolutions, Historismus took as its great subject the People or Volk, whose spirit it variously expressed, refracted, reflected, regretted, repudiated, or euphemized in its expansive theses about the progress of Geist as embodied in the spirit of a nation, the character of the Teutonic nations, the spirit of the times, etc. Web 2.0 similarly celebrates the vox populi (e.g., social media in the Arab Spring).

But I also contrasted historicism and Web 2.0. Historicism, after all, was a creature of the age of imperialism, which can be defined in one way as the use of civil, religious, and military power to impose trade and communication routes through other people’s lands so that the Western spirit of the people could become the world spirit. But the routes at that time were incomplete and difficult, not to mention steampunk-slow or (as in telegraphy) low in bandwidth. Hence, temporal delay played a central role in the story of the people. The story of the Western spirit was always unfolding (beginning, overcoming, forking, reuniting, peaking, resuming after interregnum or revolution, etc.). In fact, if you look at the temporal modifiers in Historismus (in a single passage from Ranke that I study in the essay, for example: “at the beginning of his success,” “not long after,” “he first intended,” “at length become,” “at last brought it about,” “it was not long before,” “eventually,” and “at length”), you could say that temporal delay was constitutive of the basic narrativity of the people’s story. The difference of Web 2.0 now is that cables have been laid, satellites launched, and other fast modes of communication deployed during the late colonialism we now call global neoliberalism. As a result, temporal delay recedes from view into invisible or unnarratable micro-temporalities (glitch temporalities like mistimings in the serving up of media or PHP files in a modern Web page or the unknowable delays in a Twitter stream). (I’ve just been reading Wolfgang Ernst in Jussi Parikka’s edited volume of his essays, and my argument clearly resonates here with Ernst on machine temporality versus historical narrativity, though my reading of Ranke as narrator seems antithetical to Ernst’s view of him as media recorder [perhaps due to the fact that I see historicist narration as neither the opposite nor the double of mediatic time but instead as its own, distinct apparatus of micro-temporalities].) We are thus free to believe in a universal sociality utterly unfettered by history. As I put it in my essay:

Web 2.0 … is a libertarian pygmy standing on the shoulders of a tyrant ogre…. Spatial-political barriers that once took muscular civilizations centuries, if not millennia, to traverse by pushing through roads, etc., are now overleaped in milliseconds by a single finger pushing ‘send.’ The temporality of shared culture is thus no longer experienced as unfolding narration but instead as ‘real time’ media. Specifically, the old phenomenology of store-and-forward temporality transforms into the new ideal of instantaneous/simultaneous temporality–a kind of quantum social wavefront connecting everyone to everyone in a single, shared now. (22)

Where the nineteenth century fashioned its self-image on the idea of shared history, then, our era fashions its identity on the idea of a shared network. So what is a network? Of course, there are many ways to answer that question. But in the centuries-long perspective I am sketching here, it’s useful to see network as first of all a privative construct – something that is not or that subtracts something. Basically, a network is something that subtracts the need to be conscious of the geography, physicality, temporality, and underlying history of the links between nodes. After all, that’s why we have packet switching, statelessness, TTL (time-to-live on packets), domain-name servers, and, in fact, the Internet in toto: so that we are route-independent. Increasingly, the world appears to us to be adequately represented in a social network graph in which nothing meaningful–not distance, direction, or impedance (and certainly not how many historical dead bodies lie alongside a cable) – can be read in the thin lines between nodes. (Someone should program a ping or traceroute utility that can be crowd annotated so that it shows alongside the milliseconds between hops the history of military, legal, economic, epidemic, or other interventions needed to create the route for that hop. How many Native-American Chumash along the Southern California coast had to perish from small pox during colonialism, for example, for my speed test utility program now to let me gauge the throughput of my internet connection in Santa Barbara by routing pings and downloads along the old Camino Real to a server in Los Angeles?) If the “I” of the social network generation is our contemporary ego, then history is the unconscious of that ego.

I thus understand the surging interest among media-studies and digital-humanities scholars in media archaeology and the material history of the digital to be a fundamentally analytical move: not a talking cure but a media cure for analyzing the historical unconscious of our networked age. This is true even if, in our repugnance at older regimes, we reject the name of history and call that unconscious the time of media (the aboriginal dreamtime or arche-time of the machines that are our cool spirit beings today).

But I also think that media archaeology likely needs to deepen the way it applies the Foucauldian method of “archaeology” (and “genealogy”) so that it can analyze “media, history” without recapitulating the problem of network presentism at a meta-level. The geneaological method is energized by the boundless irony, surprise, and contingency that emanates from its core hermeneutical engine, which is an anti-hermeneutical engine. That engine discovers aporias lying between (and within) epistemes – e.g., between “1800” and “1900” in Friedrich Kittler’s Discourse Networks, 1800/1900 – that blow a hole wide open in the fictions of human identity cherished by any age, and especially in the fiction of nineteenth-century historicism and hermeneutics that human identity/meaning is integral with a continuous, progressive history. A characteristic hole-making or aperture tactic of media archaeology is thus to switch our gaze between low-level technological systems and high-level technosocial systems (discursive formations or “circuits”) coexisting in a strange loop of feedback-cum-deconstruction. That way, we void the middle level between technological signal and technosocial system where past hermeneutists had assigned the strange loop such essentialized, oppressive, or, at best, boring names as self, humanity, civilization, and history. This is an emancipatory move; but in voiding the subject of history, the genealogical method risks ending up with hollow pipes between the epistemes that, at a meta-level, look just like the links between nodes in a social network graph. Only with great care and delicacy can the hollowness of those pipes be shown to be not just emptiness but instead a null or either/or channel – filled, as it were, with void – constitutive of the S/Z logic (as Roland Barthes might have put it) that gives any episteme its trickster core structure. Foucault walked that fine line well, ineffably and inimitably showing us how such lines were both thin and thick, nothing and manna (like the “Un” in Unreason in his madness book). But it’s hard for most of us to sustain that balance without our argument collapsing into apparent collections of case studies, micro-studies, and other disconnected materials (“anecdotes” in the new historicism) that merely aim to exceed empirical discontinuity (“we just have to find the missing vertebrae to piece together the whole dinosaur”) but somehow stop short of being persuasive examples of principled discontinuity (where the prefix dis names the plutonic undergod of continuity). In other words, while media archaeology wants to repudiate history rather than just unconsciously – as in presentist networks – forget history, it is always at risk of ending up with a thin, evacuated diagram of history equivalent to a meta-network. Indeed, I sometimes wonder if it would be possible to do a Foucauldian analysis of epistemes, or a media-archaeological analysis of “discourse networks,” purely through social-network graphs of nodes and links, supplemented by metrics of centrality and density as well as tools to visualize negativities that are unlinkable in the system (cannot be said in the discursive formation) except through circumlocutory hops.

The solution, I think, is not to retreat from the networked nature of media-archaeological method but to develop it even further to the point where, if the pipes of history cannot be filled again, then an equivalent effect can be produced by networked thought itself. So let me hypothesize that there is room for a build-out of media archaeology that could be called “network archaeology.” By this I mean an approach providing both a media archaeology of past networks and, recursively, an understanding of the networked structure of media archaeology itself. The approach to both halves of this problematic involves heuristically saturating media archaeology with the idea of networks – to the point where world and network coincide, with machine serving as the in-between router.

The still in-progress essay I gave as a paper at the Miami University conference, which I titled “Remembering Networks: Agrippa, RoSE, and Network Archaeology,” is an attempt at applying such a saturated network approach to the first half of the problematic I indicate: imagining what a media archaeology of networks might be. “To the best of my knowledge,” I said at that time, “we currently have no adequate media-archaeological method – and hardly any supporting preservational, curatorial, and bibliographical or descriptive method – for capturing … networks of combined past and present – oral, written, print, analog, and/or digital – media as networks, complete with the event-driven states and dependency configurations of their dynamic networking.” I should have been less absolute, since I am now seeing more attention to past networks as well as to the history of the growth and change of networks (as in Esther Weltevrede and Anne Helmond’s wonderful “Where Do Bloggers Blog? – Platform Transitions Within the Historical Dutch Blogosphere” [2012]). My paper proposed four principles of a future network archaeology, which I’ll just summarize here. First, treat individual works of media as proto- or micro-networks. This means that we shouldn’t treat documents (or, for that matter, people) as en bloc entities engaging each other in networks but should instead adopt a radically networked worldview in which it’s networks all the way down. En bloc entities – individual documents or people constituted internally as relationships of parts, levels, and stages linking and unlinking in time – are themselves network structures. Second, treat micro-networks of individual works as part of a macro-network. Among other things, this means that we should see libraries, collections, editions, archives (and other holdover, skeuomorphic concepts still prevalent in the digital humanities) as really macro-network structures that are continuous in principle with the lower-level networked entities they contain. Third, treat the past as a network. Perhaps the best demonstration of this is in my “Friending the Past,” where I try to imagine an oral village society as a local-area network based on store-and-forward principles. And fourth, treat past and present networks differently. Adapting Katherine Hayles’s notion of “media-specific analysis,” I would call this the principle of network-specific analysis. Again, a succinct example is in my “Friending the Past,” where I contrast the LAN structure of oral society with the wide-area network (WAN) structure of print societies, and then speculate about society’s new need for network mediators who serve or route mainstream communications, but who are themselves isolated from mainstream society (e.g., monks in the scriptorium, our early “servers” and “routers”). The technical-cum-methodological apparatuses we will need to string these principles together to the point where we can really see “media as networks, complete with the event-driven states and dependency configurations of their dynamic networking” will be formidable. For instance, we will likely need to integrate methods from the OAIS reference model (Open Archival Information System), computationally-assisted data lineage or provenance models in the sciences (partly influenced by OAIS), the social graph model, the actor-network theory model, and bioinformatic models of network archaeology (see, for example, Saket Navlakha and Carl Kingsford’s “Network Archaeology: Uncovering Ancient Networks from Present-Day Interactions,” PloS Computational Biology 7.4 [2011]).

Then there is the second half of the problematic I indicate: how to use network archaeology recursively to understand the networked structure of media archaeology itself. This is where we come back to the problem of history, since a solution to this issue would allow us to understand better the specific relation of similarity and difference between media archaeology and an older narrativized history. Historical sociologists such as Roberto Franzosi in his Quantitative Narrative Analysis (Sage, 2010) and Peter S. Bearman and Katherine Stovel in their “Becoming a Nazi: A Model for Narrative Networks” (Poetics 27 [2000]) have shown us how we can analyze narratives as particular kinds of network structures. We should perform such analysis on the writings of Historismus as well as on related writings in philosophy, linguistics, etc. that once carried what Lyotard calls civilizational “metanarratives.” (Such would be a network-analysis version of the kind of analysis Foucault achieved in The Order of Things.) Then we should perform similar network analysis of writings in the field of media archaeology and, more fundamentally, of the technologies modeled and described by such archaeology (e.g., machine-level process charts, source-code programs, commented annotations of programs, user documentation, etc.). How are the network structures the same, and how different? Do computers, media-archaeological writings, and historicist narratives use discernibly different network logics? Do these logics change over time in the same or different ways? Are the network logics of the human record registered in different epistemes and different media parallel, convergent, or divergent? Is network logic an open or closed system (infinite or finite in possible structural schemes)? Where, and to what degree, do old network structures continue like viruses embedded in new ones? And how do past and present machinic/discursive network structures influence institutional or organizational structures (a vital intermediary issue, I believe, in any effort to connect media archaeological research to cultural criticism in the age of neoliberalism; but that is another topic).

I wager that if we can develop a network archaeology that can open up questions like these and suggest ways to explore them, then we will have de facto regenerated for our times, on our own terms, a sense of history – i.e., a sense of the relation between past and present that is not just a thin, empty line but a multiplex band of signals, inscriptions, textures, renderings, and finally experience that is human presence enough for our dreamtime of machines slaved to, and enslaving, social systems. I suspect also that the character (which is also to say the micro-devices and -temporalities) of such a post-historical sense of history will be fundamentally recursive and emergent rather than narrative. But that is to be explored.

Recurring to the public-engagement issue, which seems to be my home chord in this interview: I do agree with you that the “last mile in … a project of reengagement might be the task of connecting the historical consciousness/conscience of humanists with the presentism of network culture.” That’s one of the reasons I am reluctant to give up on the idea of history in the age of networks. One of the key traits of humanistic work is that it relies on a vital historical understanding to drive, extend, shape, and criticize its equally vital engagement with the present. This is why even such new humanistic fields as ecocriticism, cognitive approaches to literature, GIS in history, and science and technology studies are populated by scholars who–individually or in concert–address both our contemporary world and such historical contexts as “green” in the Early Modern period, cognition in nineteenth-century novels, railroads and the American Civil War, visualization and the history of medicine, etc. The ability to balance attention to the old and to the new, I think, is one of the unique features of humanistic work that should be put before the public as a humanistic contribution to society. Indeed, when I polled humanities faculty at my university in 2010 to get a sense of what they thought basic research in the humanities involved and how it could contribute value to society (part of my research for the working group of the UC Commission on the Future that I mentioned), one of the goals they identified as most central was “the discovery, preservation, and communication of the historical and present record of human society” (see my report on that poll). My colleagues saw themselves to be engaged in the relation between history and the present. Whether they are narrators, mediators, translators, interpreters, critics (and so on) in thus routing between past and present is a secondary concern. This is one of the reasons that the piece that I wrote for the 4Humanities “Humanities, Plain & Simple” initiative (“The Humanities and Tomorrow’s Discoveries”) argued that historical awareness is a key feature of any true discovery (as contrasted with scientific and other “inventions” that by themselves do not come up to the bar of humanly and socially meaningful discovery). “Most fully,” I said, “discovery is what happens when we apply an understanding of human history, cultures, values, and languages to inspire, shape, or influence the creation and reception of breakthroughs.”

I don’t think there can be a place for the humanities in a networked world without any sense of history; and the world would be the worse for it. So the humanities (led in this context by fields like media studies and the digital humanities) need a network archaeology that can bolster a sense of history for our times – one more multifaceted and inclusive (of social-cultural-geographical differences today as well as the dizzying, disturbing, to-be-learned-from, and ultimately humanizing differences of the far past) than the time lines created by Twitter and Facebook asking us “what’s happening?” and “what’s going on?”

Article: Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Image: "Introduction: Paragraphs 4-5”

From: "Drawings from A Thousand Plateaus"

Original Artist: Marc Ngui

https://amodern.net/artist-profile-marc-ngui/

Copyright: Marc Ngui