China’s agrarian culture celebrates the lunar New Year as the most important time of the year. Nianhua (New Year pictures), a woodblock art form widely consumed by the rural and sub-rural population, constitutes an essential part of such celebrations. At the peak of its popularity in the 19th century, nianhua employed woodblock printing to produce large amounts of pictures that were sold throughout the country, although the subsequent introduction of lithographic printing drove it out of business due to its relative affordability and speedy printing.

While the genre was often dismissed in the late Qing and early Nationalist periods, Chinese communists showed intense interest in it in the 1930s for the purpose of political propaganda. Under the influence of Lu Xun, the father of Chinese modern literature, who fervently promoted woodcut prints as a propaganda tool to educate and inspire the masses, the communists in Yan’an, the command center of the Party between 1936 and 1948, came to see the significance of the print in communicating with peasants and began to study the genre vigorously. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, articles centering on nianhua began to emerge in Chinese journals. As some researchers, such as Cai Ruohong (1950), Wang Chaowen (1950), and Ai Zhongxin (1950), were mainly interested in examining the strategies in better appropriating the art to serve political purposes, critics such as Sun Xun (1955) and Mu Xun (1957) praised the merits of traditional nianhua and criticized the practices of forcing the art into the service of politics without respecting its unique aesthetic principles. In 1954, as a Chinese literary theorist, critic, playwright, and writer, A Ying published A Brief History of the Development of Chinese Nianhua, the first book of its kind to chronicle the evolution of the genre. Wang Shucun, a native of Yangliuqing, is an art historian and the most prolific writer who had published more than a dozen books on the subject. More recently, in the early twenty-first century, Chinese writer, painter, and social activist Feng Yicai began to write extensively on nianhua as part of his project of preserving China’s folk cultural heritage.

Only a few scholars focus specifically on the genre, and the relationship between nianhua art and the Communists has often become the center of their discussions. In particular, Ellen Johnston Laing and James A. Flath have addressed a wide range of topics about different stages of nianhua’s development. Laing examines the New Year prints from the 1930s and the socialist era in her book The Winking Owl: Art in the People’s Republic of China. Similarly, Flath’s The Cult of Happiness investigates both production and representation of the woodblock print in the rural north of China between the late Qing period and the mid-twentieth century. Other scholars have centered their analysis on the period when the Communists first incorporated it into their service. Art historian Shaoqian Zhang analyzes how the Communist regime employed the propaganda prints including political posters and woodcuts as a weapon during the Second Sino-Japanese War and the post-war period. Putting more emphasis on audience reception, Chang-Tai Hung explains how Chinese peasants initially resisted new prints devised by the CCP which, out of practical necessity, had to switch from abstract Western woodcuts to indigenous folk art. Distinguished from Hung’s focus on the audience, Yan Geng concentrates on the creators of the art as he addresses new nianhua during the transition period of the early 1950s, when artists like Li Keran had to change their old methods to satisfy the cultural policy of the Communists.

In summary, these discussions are insightful and useful to help us understand the unique art form, yet there remain large gaps in our knowledge about the genre before the rise of the Communists. So far there has only been very limited attention paid to the art form in earlier stages. For example, Laing has examined wealth gods and the early political prints while Flath considers the themes of transportation, Western technology, and social dimensions. Therefore, this article analyzes major themes in nianhua prints during the late Qing and early Republican periods. In what follows, I shall first introduce the history of nianhua and the prejudice against the art common among Chinese elites in the early 20th century. Then I will focus on the print specifically in the late Qing and the early Republican era and, through surveying the artists’ engagement with human agency, themes of dissent, and representations of modern women, illustrate their political goals and social ideals.

As the name of the genre suggests, nianhua products are meant to be consumed once, then torn up, and thrown away. And during the time period under review many, Chinese elites failed to recognize its value as an art. The prints we see today constitute only a small proportion of an enormous production that have been lost to time, and many prints are found today in archives and museums in Russia, Japan, and the United States as well as China. Partly due to these reasons, the genre remains comparatively understudied.

Scholars have examined the relationship between the printing press and political developments and print and changing social norms. Rudolf Wagner, for example, divides the Chinese public sphere into two tiers: the upper class of the Qing court, and the lower tier of the literate and the lower class of the society. Similarly, Joan Judge states that public opinion in journals and newspapers offered a fourth type of representation in addition to the other three; namely, the imperial mode, the official mode, and the elite mode. Building on this scholarship, this article asks: how did folk artists use nianhua to comment on social and political changes? And what is nianhua’s place in the developments of Chinese print cultures?

The History of Nianhua

To answer these questions, let us now turn to the history of nianhua. The practice of hanging New Year pictures for good luck can be traced back to hanging peach wood charms and amulets on gates and doors to dispel evil influences on New Year’s Day in ancient China. As woodblock printing, invented and perfected in the Tang (618-906) and Song (960-1279) periods, contributed to the development of the artifact, economic expansion during the Northern Song dynasty opened up markets for its consumption. Through comparing the earliest nianhua with religious wall murals from the Tang and Song dynasties, Chinese historian and critic A Ying came to the conclusion that nianhua was originally created by religious painters and woodcarvers in the Song dynasty.1 Although the print form was created initially for religious purposes, the influence of religion gradually declined and secular themes increased in the Qing dynasty, deriving artistic inspirations from opera stories, historical stories, maidens and babies, flowers-and-birds, and current events.2

In the late Qing era, the name nianhua, meaning “year picture,” came to replace all other names such as huapian in Beijing, huazhang in Suzhou, huazhi in Zhejiang, shenfu in Fujian, and doufang in Sichuan. The words “nian hua” first appeared in Li Guangting’s writing, yet it became popular only after the Hundred Days’ Reform (Wuxu Reform) in 1898 when the Qi Jianlong print shop published Reform New Year pictures (gailiang nianhua) that promoted education, equality between the Han Chinese and the Manchus, and the banning of opium. Its name, therefore, indicates that the genre is, first of all, paintings made by woodblock printing, and secondly, that the decoration is closely linked with the holiday. However, in practice, the genre goes beyond the function that its name indicates: it covers every aspect of folk life as it is used not only to decorate doors, windows and walls, but also for fans, slideshows, lantern slides, games, and for occasions such as weddings, funerals, birthday celebrations, ceremonial prayers, ancestor worship ceremonies, apprentice ceremonies, and more. Additionally, at the end of the nineteenth century, the genre started to include current events, news, and innovation and the prints were not necessarily posted during the New Year.3 There is even a suggestion to rename it as “popular woodblock print” by Ellen Johnston Laing. She points out, “These prints, erroneously known as nianhua, or “New Year’s pictures,’ in reality depicted a wide variety of subjects for use not only at New Years’ time but also during the year.”4

The folk art was very popular among Chinese peasantry as millions of copies were made and distributed across the country in the late Qing period. During the Xianfeng era (1850-1861) and Tongzhi era (1861-1875), twenty print shops in Yangliuqing occupied half a block on the main street and each shop was equipped with a dozen tables on which prints were made. The Dai Lianzeng shop alone produced one million prints annually. When the business spread to Chaomidian, twenty-nine villages and sixty shops became involved.5 Another survey taken in 1927 accounted for the movement of the goods from suppliers in Tianjin to retailers in the far north, west, and east of China. It recorded that products going east were shipped to Fengtai and transferred to three Eastern provinces (Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning), Jehol, and Mongolia, while goods going westward went on trains to Guihua County in Datong and were transferred to Shangxi and Gansu areas through Shanxi and Xinjiang. Originating at Tianjin, the route covered the northern half of the whole country.6 However, it is obvious that these products travelled further east and north since Japanese consumers? first discovered Chinese nianhua not in China but in Korea, and Russian and Japanese museums boast decent collections of the genre.

The reasons for the popularity of the prints among Chinese peasants could be explained as follows. The purchase of the prints was often associated with family reunions, joy, fun, feast, and satisfaction. The ability to afford the prints itself proved the success of the past year and the print would bring the good luck much needed for the coming year. The purchase of the prints triggered great memories and good feelings. As Feng Di aptly observed,

It might mean nothing to the intellectuals but the consumers love and respect it. In poverty-stricken villages, poor people do not have money to buy many copies but they have to go to the market in towns to look at them at the shops. Most of the village women and men toil all year round and they only have a few days off for entertainment in the New Year. No matter how poor they are, they will buy one or two. Sometimes they trade their food for the prints. That is how we know how much they need the pictures.7

Second, both the artists and the consumers shared interests and concerns. Many of the artists were from rural backgrounds; they worked the land during spring and summer and used breaks in autumn and winter to make arts. People involved in the artistic production included print designers, engravers, printers, and those who were in charge of colors, although most of them remained anonymous. While male artists were usually in charge of the earlier stages such as carving the woods, women took agricultural slack seasons to work on the last phase, usually the most time-consuming in the whole process, and dabbed colors onto the prints with their hands. From generation to generation, mothers-in-law passed on acquired knowledge and techniques to daughters-in-law in villages.8

Third, the prints communicated through visuals and vernacular speech that were comprehensible to a range of audiences. Before the widespread presence of the news press began to change the Chinese cultural landscape in 1895, methods of passing information to rural areas had been limited to governmental posters and notices, and oral exchanges of information in market places. Nianhua was one method of spreading information that was left out of the official records as it was commonly believed that its main function was to entertain instead of spreading information. However, with their mimetic capability, visual images convey ideas and concepts vividly and sometimes more efficiently than written texts and beyond the limit of literacy. The advantage of the visual communication was so evident that it is not surprising that the earliest printed books in China, The Buddhist Sutras of the Tang, were replete with illustrations.

Nianhua and the High-Minded

Nonetheless, nianhua remained a marginalized genre as it was either simply ignored or generally denounced as aesthetically inferior, disreputable, and vulgar during the late Qing and early Republican periods. The lowly social status of the makers and consumers of the art could partially explain this neglect. The makers of the genre were mostly folk artists who had. often had limited education and passed on techniques and skills from generation to generation, and they were associated with peasants, fishermen, and woodcutters. Because a print was replaced yearly by a new one with the old being tossed out and the new replacing the old, few prints were well-preserved for observation during those days. It was made of thin paper, vulnerable to the weather, and difficult to preserve.

In early twentieth century Chinese journals, the genre was accused of being superstitious for its connection with religion; many contemporary intellectuals believed that written texts were more sophisticated than visuals; and its fascination with eroticism and daily life led many to perceive it as vulgar and frivolous. Accordingly, through the new journals, high-minded elites castigated it as an obstacle to China’s modernization during the late Qing and early Republican periods. Some described it as an embodiment of backwardness and fengjian (feudalism) and said it was shallow, naïve, laughable, and superstitious.9 Others condemned it as money-worshipping and escapist.10

On the other hand, as a fervent defender of modernity, the literary critic Lu Xun showed great interest in the genre through his writings between the 1920s and 1930s. He spared no efforts in chronicling its development, warned about the danger of losing the tradition, and encouraged youngsters to revitalize it as part of Chinese cultural identity. Nonetheless, despite boasting a good collection of the prints and their importance to his promotion of Chinese culture, Lu Xun never offered a direct comment on the genre, leaving scholars of nianhua on their own to distill his thoughts from his writings. What was appealing to him was the techniques and skills of woodblock printing that, he believed, could be used to spread revolutionary ideas to bring out reforms and social changes. He recalled two pictures from childhood, The Mouse’s Wedding and The Marriage of Pigsy, and commented that Pigsy was unattractive while the mice looked like Chinese scholars for their slender legs and high cheekbones. His critical embrace of the genre and advocacy for its utility if reformed is illustrated by the following quote:

Though these (colored New Year pictures and the picture-books) may not be genuine producers’ art, undoubtedly they were opposed to the art of the leisured class. Even so, however, they were much influenced by consumers’ art. … This transformation is usually known as ‘vulgarization.’ It could do no harm, I think, for artists who are concerned with the general public to pay attention to these things, but of course it goes without saying that they should be improved upon also.11

Many high-brow intellectuals disparaged it during the late Qing era. Subsequently, when the Nationalists came into power, rather than lifting the genre out of its oblivion to a position of social respectability, the government established censorship to control its production and circulation. One newspaper expressed its disbelief that the government had decided to censor New Year pictures in Hebei Province, as the Education Department was requiring shops to send in products for inspection. Among all the prints submitted, nineteen were allowed to be made; seven obtained temporary permissions for publication including Abundance in Four Seasons, Happiness of the Fisherman’s Family, Three Humble Visits to a Thatched Cottage, and Happiness and Longevity; thirteen prints such as Fortune Boy, Heaven Granting Gold, Taishi Shaoshi (two official positions without actual power), and Live Money God Arriving at My Home did not acquire permits at all.12 Quickly, the follow-up report in the next issue justified the censorship and even further suggested the government ban erotic content and eliminate superstitious elements to safeguard the public well-being.13

The capability of nianhua to reach audiences in rural China received more sustained attention in the 1930s when the Communists exploited its influence to mobilize peasants in Yan’an. Chinese Communists recognized that the success of the socialist revolution could not solely depend on the intelligentsia; China was fundamentally an agrarian country so, if the Chinese Communists wanted to achieve the goals of revolution, they had to engage both urban workers and rural peasants. The traditional artifact which already enjoyed significant popularity in the rural areas became the perfect tool for propaganda.

However, the Communists were not the first to use the popular prints for political purposes according to Ellen Johnston Laing. In her examination of Chinese popular woodblock prints (minjian banhua), lithographed journalistic pictorials (huabao), and pictorial advertising (yuefenpai) for themes of reform, revolution, politics, and resistance between 1900 and 1940, she concludes,

Although most popular print production was destined for religious, decorative, journalistic, or daily use purposes, a small number of prints were deliberately contrived to convey specific social or political messages, proving that the value of using the popular print idiom for propaganda and political purposes was recognized and used before the Communists in Yan’an turned to this method of reaching the people.14

Laing’s analysis demonstrates that Chinese popular prints, had long been engaged in politics.15

Common Man, Front and Center

In contrast to literati paintings which often downplayed the importance of humans, nianhua accentuated human characters. Human figures, the essential subject of nianhua, were not typically the focus of traditional painting in comparison with sublime nature. In the Qing period, Chinese literati did not treat figure painting as a serious or noble undertaking, compared to landscape paintings which were held in the highest regard. As Sherman E. Lee notes in his analysis of the literati tradition in Chinese painting, “In general, figure subjects were not in the accepted realm of the literati school—such mundane matters were left to the professionals.”16

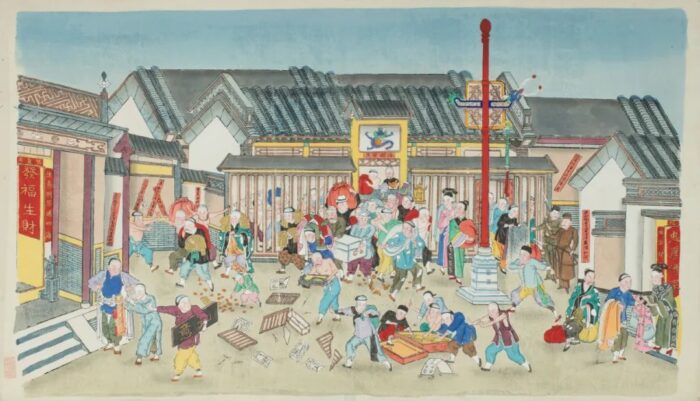

Fig. 1: Scholars, Farmers, Artisans, and Merchants, Yangliuqing, 59×98cm; Qing Dynasty, Folk Art Museum of China Academy of Art.

In such a historical context, nianhua’s focus on commoners and their life is subversive in that it persistently insisted on putting a spotlight on a marginalized group. Deeply concerned with the experience of the lower class, nianhua offered an opportunity for the folk artists to represent common people and their life in a pictorial art form. This is illustrated in the New Year picture Scholars, Farmers, Artisans, and Merchants above (Figure 1), The picture depicted the four traditional social classes of scholars (shi), farmers (nong), artisans (gong), and merchants (shang). However, in Scholars, Farmers, Artisans, and Merchants, four social classes appear in harmony within the same frame without stressing the designated hierarchy and the natural environment functions as merely a background. The fact that the characters representing each social group look at one another indicates the connection and dependence among them.

What emerges in the nianhua genre is the focus on the human form. Indeed, Wang Shucun points out that there are two types of pictorial arts in China; namely, Chinese painting and minjian nianhua (popular New Year pictures). The first focuses on landscapes, flowers-and-birds, rocks-and-bamboo, orchids, horses, and animals, and deliberates less on human figures. In contrast to the former, the latter concentrates on humans, deriving inspirations from historical novels, legends, folk life, and historical events, while paying less attention to landscapes and flowers-and-birds.17 Nianhua historian A Ying also asserted the importance of human subjects in nianhua. In his analysis of why European copperplate print, when first introduced to China, did not become popular, he attributed its failure to the fact that nianhua focused on humans while copperplate did not.18

Nianhua placed humans at the center, so much so that the genre developed its own aesthetics in representing human characters. For instance, the genre accentuates humans through full-body portraits and almost exclusively features head-on faces, representing faces at a three-quarter angle only when one has to. It also has strict rules about describing humans in their perfect postures. Furthermore, the artists come up with different shapes or styles of faces for different people: square for a man, sunflower-seed-shaped for a woman, big and round for a baby, and colorful for an opera actor.19 Also, the renowned nianhua scholar Wang Shucun observes that, in contrast to some who argued that thick eyebrows and full lips constitute the realistic and healthy image of the working class, nianhua does not exaggerate physical differences between peasants and people from other classes. Although there were some visual cues differentiating peasants and literati, the nianhua artists studied here largely represented them in similar ways.20

On the one hand, topics focusing on agrarian productions such as Busy in Farming, Busy Farmers, February 2 of Lunar Year, and Big Ox, represent the daily life in an agrarian society where peasants are tilling the soil, plowing, and cropping in the field. On the other hand, A Temple Fair in the Village and Get-together on the Dragon Boats depict activities after farming seasons. These narratives of rural life in a village community tell stories of ordinary people, and are fun, colorful, and alive, in sharp contrast to the monochrome imagery of the literati paintings.

In summary, nianhua makes common people, especially peasants, its protagonists, and portrays them as resilient, courageous, and active in their interaction with the surroundings. Here, the reality of the peasant life becomes the focal point of the art, something rarely seen before in the history of Chinese art.

Centering on agricultural experiences, nianhua expressed pride in farming and, to remind the viewer of the importance of agriculture, the prints depict the ruling class joining agricultural production and working in the fields. For example, the print Eryueer Longtaitou Festival depicts a scene on the second day of the second lunar month, a date in which a dragon awakes, raises its head, and signals the arrival of spring. An emperor in peasant’s clothing is ploughing rice paddies following an ox while his officials are sowing, the queen is delivering food to the field, and his guards are directing another ox. Similarly, in Judge Bao Harvesting Wheat, a eunuch announces the emperor’s order that Bao take his official post immediately. However, an inscription on the print speaks in Bao’s voice, “I will go after I am done with the wheat.” Judge Bao, a symbol of justice, is a well-known official around the 11th century who fought against corruption and abuse of power. Depicting the most respectable official as one of the peasants working in the field, the print stresses the critical role of agriculture in Chinese society. It also precedence to cutting wheat over obeying the emperor’s order. By imagining emperors and officials working together in the field, the prints foreground the significance of agriculture.

The Dissidents

The genre also encourages the viewer to question authorities by denouncing kingship in a carnivalesque style. In the book The History of Chinese Printing, Zhang Xiuming concluded that “Nianhua is not only used to enrich people’s cultural life but also as a tool to satirize political corruption and fight against imperial aggression.”21 To circumvent official retaliation, the artists often used humor to indirectly criticized the authorities through satire. Emperor Yang of Sui Travelling to Jiangnan from the late Qing period, for instance, criticizes the lack of dignity and decadence of the emperor who orders a group of eight women to haul his ship while he and his companions are on board enjoying the view. The women trip over one another and the chaos provokes laughter. The power relation is reversed in this case since the emperor is turned into the object of ridicule, while the audience assumes the position from which to laugh. As Bakhtin points out, “this [carnivalesque] laughter is ambivalent: it is gay, triumphant, and at the same time mocking, deriding. It asserts and denies, it buries and revives. Such is the laughter of the carnival.”22

While some picture used historical events to critique the present, others directly commented on contemporary events and challenges government authority. Of course, such a public protest could come at a heavy price as it often resulted in the woodblock plates being split in court by the officials to prevent more copies from being made. The peasant painter Liu Mingjie (1857-1911) produced the print Empress Dowager Cixi Fleeing to Chang’an. The picture, also named Empress Huiluan tu, deliberately alluding to the famous wall mural from the Song period (968-1022) which shared the same name, was designed to mock the Empress Dowager Cixi who abandoned her subjects and fled Peking when the Eight-Nation Alliance captured the city in 1900. The original mural, commissioned by Emperor Zhenzong to worship the God of Tai Mountain, consists of two scenes: Qibi tu, depicting the god setting off for inspection, and Huiluan tu, in which the god is returning to his palace. The original painting displays the god’s supremacy by featuring 697 figures in total including both military personnel and scholar-officials. In sharp contrast to the grace and grandeur of the god’s tour, Cixi’s “tour” was actually a narrow escape from the foreign powers in an ox-drawn wagon as she disguised her true identity as the empress of the country in peasant clothing. By juxtaposing Cixi’s disgraceful flight with the supremacy of the god, the print cleverly used irony and sarcasm to question the regime and mock the corruption of power.

To expose social evils, the artists found creative ways to evade censorship by appropriating homophones, as illustrated by the disarmingly comic pictures such as A Farmer as a County Magistrate Having Difficulty Communicating, Shave One’s Head to Shape Facial Features and Tailor Makes a Straight Line. Here, homonyms are appropriated to condemn the incompetence and corruption of the government. During the late Qing period, selling official positions was widespread. The print A Farmer as a County Magistrate Having Difficulty Communicating depicts how after a farmer purchases a post, he misunderstands the question from his superior to the amusement of the audience. Similarly, in Shave One’s Head to Shape Facial Features, the Chinese words for facial features are pronounced as wu guan, which sounds exactly the same as “five officials.” Hair dressers were not allowed to become officials in the Qing dynasty due to their low social status. Hence, Shaving One’s Head to Shape Facial Features shares the same pronunciation as “hair dressers become officials.” Through this strategy, the print criticizes the illegal and unfair practices in selecting court officials. Likewise, in the print Tailor Makes a Straight Line, the words zhixian could mean “straight line” and “county magistrate.” Therefore, the sentence could also mean “A tailor makes a county magistrate.” Like hair dressers, tailors are not official material. If a tailor makes a country magistrate, it can only mean he buys an official title and paves his way to success through corruption. It is important to note that such a practice of using homonyms to ridicule and expose social ills in nianhua was not rare, but a common tendency shared by the “expose narrative” (qianze xiaoshuo) which was widely consumed by Chinese readers during the late Qing period.

Long before the communists, Nianhua artists depicted revolutionary heroes who dared to challenge the authorities. Visually, heroes in the genre are often depicted brandishing weapons, such as hammers, swords, staffs, spears, tiger forks, and rope darts, attheir rivals. Of course, such scenes of violence were forbidden in the more esteemed arts of the literati. Although the stories favored in the prints are frequently associated with blood and death, the actions are often justied as self-defense or revenge. The Fisherman’s Revenge, for instance, inspired by the popular Peking opera with the same name, shows the protagonist Ruan Xiaoqi and his daughter taking a boat on their way to kill the village bully and his family. As one of the heroes from Chinese classic literature Outlaws of the Marsh, Ruan suffers from social abuse and injustice and his actions in the eyes of many viewers are justified. Other outlaws in the same novel are also popular and there is 108 Heroes of the Marsh listing all the rest of the heroes. Similarly, the “Dashing King” in Li Zicheng Declaring Himself a King is a leader of an uprising who brings an end to the Ming dynasty. Other prints such as The Dowager Empress He Curses the Throne also tell empowering stories of defiant characters who seek justice for themselves.

Indeed, one of the most recurring themes of all prints seems to be rebellion against authority. Take the print The White Snake as an example. It depicts a famous fairytale which concerns the white snake and the green snake, who battle against a devout Buddhist. The story appears in many art forms like the ballad, drama, opera, pingshu, and New Year picture. In turn, Water Battle and Flooding Jinshan Temple vividly capture the protagonists in action while the female demon uses magic to flood Jinshan temple where the monk holds her husband. It is subversive yet inspiring because the female outlaw challenges the man in power in the name of love. Similarly, another popular print Nezha Conquers the Dragon King also questions the leadership as the title character, a seven-year-old child, fights the dragon king of the Eastern Sea, the head of the Four Sea Dragons, who abuses his power by refusing to provide sufficient rain while taking little children as sacrifice. In Marriage of the Fairy Princess, a celestial maiden falls in love with a young man against the rules of the Emperor of Heaven. Also, similar to battling the authorities, stealing from the powerful, an act of transgression, is also a frequent topic.

Plenty of prints displayed political and social engagements as they helped develop public opinion in the early twentieth century. The Opium Wars in the mid-19th century served as a wake-up call for many Chinese when they came to realize that the Great Qing might actually collapse. In response to the newly emerging interest in information concerning the battles and the following negotiations between China and foreign powers, there appeared prints depicting actual battle scenes, like Military Ships of Taiwan, Bombarding North Cathedral in Beijing, A Victory in Beijing Supervised by the Commander Ling Yuying, Liu’s Army Achieving Great Victory, Bombarding Japan, and Two Countries Getting Along.

Fig. 2: Beijing Residents Looting Pawnshops, Yangliuqing, 63×109cm; Qing Dynasty, Tsinghua University Art Museum.

Furthermore, nianhua offered a non-official perspective on major events. The subversive potential of the genre is effectively illustrated by the picture Beijing Residents Looting Pawnshops (Figure 2) that was printed in 1902 and shows a riot as a result of rising tensions between the rich and the poor. In 1900, as the foreign armies entered Beijing as part of the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion, Beijing residents stormed pawnshops and stole merchandise. Anger and panic boiled over after the empress escaped Beijing while many Qing officials either committed suicide or went into hiding. As law enforcement disappeared from the streets, looting, home invasion, and robbery occurred.

To understand the subversive potential of the picture, we must first address written accounts of the events. Written accounts of the incident mostly aligned with those of the government and gentry class. One account of the incident was written in the form of journal, recording what the author saw and heard, from the perspective of a resident whose given name was “Zhong Fang” and who lived outside Xuanwu Gate at the time. According to Zhong, on July 24th, 1900, after the foreign forces came into the city, banks, cigarette shops, grain shops, pawn shops, clothes stores, silk shops, and secondhand clothes shops, both inside and outside Beijing, were all robbed.23 Another account also indicates that pawnshops, secondhand clothes shops, grain stores, and silk stores were all robbed by mercenaries, unruly troops, foreign soldiers, and bandits.24 A scholar named Yun Yuding from Hanlin Academy similarly reported that the poor robbed and emptied grain shops and pawnshops within a few days, the riot spread to other shops, and the whole market was shut down.25 These narrators, who were well-educated and probably property-owners, depicted chaos as caused by outlaws, bandits, and the poor.

In contrast, the printed picture does not give such a definitive moral answer or choice between a chaotic or ordered kind of narrative, and its resistance to the structures of power finds its expression in ambiguity. Rather the picture provides a less alarming narrative, giving an account of the same incident from a non-official perspective. First of all, the print calls the people involved in the incident “Beijing residents” rather than looters or robbers. Secondly, it seems to suggest the incident as an act of protest as regular residents vented their rage against injustice or a typical act of “robbing the rich and assisting the poor.” The participants in the print are portrayed as actors in a suppressive system that has treated them as the compliant objects of the ruling elites. A quick glimpse of the picture would by no means bring the word “anxiety” to mind. Instead, it gives the impression of jubilation rather than horror. Female and male onlookers are drawn by the boisterous scene and watch at close range. Some men have merchandise clasped in their arms and some are carrying chests and boxes full of booty while broken furniture and shattered windows are scattered on the floor. A woman living nearby are depicted trading plunder with a man. One also sees a monk and a Daoist in the back taking things that do not belong to them. The looting is collective as everyone is depicted in a similar fashion without distinguishing individual characteristics and the participants are members of an equally-oppressed community.

New Women

Nianhua artists did not dwell on the anxieties over changing gender roles like the urban elites did in magazines, but rather shifted their attention to reflecting and celebrating the freedom and visibility of urban women as symbols of insubordination as well as modernity. Before the twentieth century, women had long appeared in nianhua in the forms of goddesses, ancient beauties, farm girls, and housewives, often visual spectacles for the male gaze. However, from the early twentieth century, the figures of the ‘New Woman’ and the ‘Modern Girl’ in the forms of military women, educated women, and courtesans joined the repertoire of nianhua prints, which I shall examine in the following paragraphs.

As a genre, nianhua paid close attention to the development of women’s issues during the early twentieth century. It reacted quickly to the changes of women’s place in the society as it embraced the new images of modern women and shifted from depicting them in domestic spaces with bound feet attending to husbands and children to representing women enjoying themselves in public. One article in 1934 noticed the growing number of representations of women in nianhua; “If you take a look at nianhua stalls in Shanghai, images of women are all over the place. Although there are not as many nianhua representing women in inland areas, there are certainly more now than before.”26 Pictures with modern women appearing in public spaces not only reflected the radical changes taking place in the society, but also challenged older conceptions. Pictures such as The Newly Built Railway and a Train Leaves for Wusong in Shanghai, The New Floating Bridge from Tianjin to Hebei and The New Street outside North Gate in Tianjin show women travelling in horse-drawn carts across the cities, while Streets in Tianjin One features two girls riding bicycles in an urban setting.

The images of educated women and women in the military in the pictures invited the viewer to identify with the reformers and the nationalist project of state building during the late Qing as well as the republican periods. A girl wearing a red coat and a blue skirt in A Girl Waving a Fan holds a book in her left hand. Teach and Learn in a Lady’s Boudoir and Women Pursue Learning promote women’s rights to education. Furthermore, nianhua turned the experiences of the Women’s Northern Expeditionary Corps, which contributed greatly to the 1911 revolution, into pictures like Female Military Drill, Cavalry Unit from a Girls’ School, and Military Drill at a Girls’ School. These prints, on the one hand, emphasized traditional norms of femininity of women through their wardrobe, but on the other hand, depicted women as ready for militant action.

The fact that courtesans appeared regularly in the prints speaks to the important roles that they played in social life. Such an arrangement does not necessarily idealize courtesans, but it does view them as an integral part of Shanghai’s modern society. With high profile courtesans such as Sai Jinhua, who allegedly persuaded the German commander to spare the lives of Beijing residents during the Boxer Rebellion, courtesans took on a prominent public image in Chinese popular culture. Courtesan literature such as Flowers of Shanghai drew the attention of the most prominent thinkers of the time such as Lu Xun, Zhang Ailing, and Hu Shi. In his analysis of the late Qing fiction for signs of modernity, David Der-wei Wang points out that courtesan literature creates defiant and independent heroines and challenges traditional moral and ethical attitudes. He asserts that “the female characters in courtesan fiction may well have prefigured the emotionally and behaviorally defiant postures of the ‘new women.’…women who are unafraid of pursuing their romantic, economic, and political desires. …the late Qing male writers, by portraying unconventional libertine women, opened the door for new gendered subjectivity and relationships.”27

However, unlike the social satire of courtesan literature, nianhua depicted courtesans as the most visible emblems of urbanization, modernization, and commercialization. Courtesans in Top 10 Scenes of West Lake and Sightseeing on a Colorful Boat, Ten Beauties Kicking a Ball, and Ten Beautiful Famous Courtesans of Shanghai appear to be urban spectacles and trendsetters rather than symbols of moral danger. In her interdisciplinary study of Shanghai courtesans, Catherine Vance Yeh remarks,

The Shanghai courtesan of the late Qing established herself as the city’s first modern professional woman. She was the first to articulate the manner in which urban women would behave, and in many aspects, her lifestyle and habits prefigure those of the Shanghai urbanite of the Republican period.28

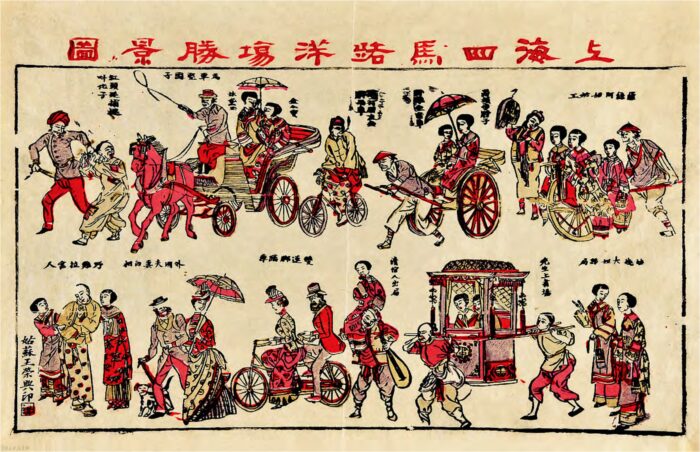

In turn, Spectacles of the Foreign Field on Four Road in Shanghai (Figure 3) illustrates, in addition to a foreign couple and an Indian policeman, professional women on Four Road in Shanghai International Settlement.

Fig. 3: Spectacles of the Foreign Field on Four Road in Shanghai, Taohuawu, by Wang Rongxing, Qing Dynasty, Shanghai History Museum.

This image includes factory girls, courtesans Lin Daiyu and Jin Xiaobao, female pingshu performers, and a female musician. Besides showing interest in the women’s different class backgrounds, the picture also draws our attention to the various ways these women travel to work in the city. Some sit on a wheelbarrow; some take a horse-drawn carriage; some enjoy a ride in sedans; some walk; some ride bicycles. Through these details, the picture, among many others, conveys to the viewer an image of a treaty port, a unique space of ethnic and cultural heterogeneity, where different classes, cultures, and social forces interact. However, this celebration of the figure of the courtesan at the end of the nineteenth century through courtesan literature as well as visual representations in nianhua prints soon faded as reformers in the 1920s started to criticize the sexual exploitation and abuses related to pleasure quarters, and linked the image of courtesans with the weakness of the nation.

Conclusion

As an overdue attempt to explore the capacities of these formerly neglected materials, this paper sets out to show that nianhua, although often accused of being simplistic, primitive, and vulgar, was truly revolutionary and complex. Interlaced with references to the creators’ observations of real life and the peasant customers’ living conditions, the genre actively engaged with politics, and expressed the artists’ attitudes toward social changes and political goals. By examining the themes of human agency, recurring celebration of revolutionaries and dissidents, and depictions of modern women in the late Qing era and the early Republican period, this paper argues that the genre offered a heterogeneity of voices that articulated desires, dilemmas, challenges, and crises experienced by contemporary Chinese peasants.

A Ying 阿英, Zhongguo nianhua fazhan shilue 中国年画发展史略 [A Brief History of the Development of Chinese New Year Picture] (Beijng: Zhaohua meishu Publishing House, 1954), 4. ↩

Wang Shucun, 王树村,zhongguo minjian nianhua shilunji中国民间年画史论集 [A Collection of Essays on the History of Chinese Folk New Year Picture] (Tianjin: Tianjin Yangliuqing Huashe Publishing House, 1991), 38. ↩

Wang Shucun, Wang Haixia 王树村,王海霞, Nianhua 年画 [New Year Picture] (Hangzhou: Zhejian Renmin Publishing House. 2005), 26. ↩

Ellen Johnson Laing, “Living Wealth Gods’ in the Chinese Popular Print Tradition,” Artibus Asiae, vol. 73 no. 2 (2013), 343. ↩

A Ying 阿英, Zhongguo nianhua fazhan shilue 中国年画发展史略 [A Brief History of the Development of Chinese New Year Picture] (Beijng: Zhaohua meishu Publishing House, 1954), 27. ↩

“Diaocha: Yangliuqing Huaye zhi Xianzhuang” 调查:画业之现状 [“Investigate: The Current Condition of Yangliuqing Printing Industry”], Jingji banyue kan 经济半月刊 [Economics Quarterly] vol.1 no.3 (1927), 96. ↩

Feng Di, 冯棣,“tan nianhua” 谈年画[“Talking about New Year Picture”]. Minzhong zhoubao (Bei Ping) 民众周报(北平) [People’s Weekly (Bei Ping)] vol.2 no.1 (1937), 31. ↩

Wang Shucun 王树村,zhongguo minjian nianhua shilunji 中国民间年画史论集 [A Collection of Essays on the History of Chinese Folk New Year Picture] (Tianjin: Tianjin Yangliuqing Huashe Publishing House, 1991), 20. ↩

Gao Yushuang 高玉爽, “nianhua er” 年画儿 [“New Year Picture”]. Tiandi ren(shanghai) 天地人(上海)[Heaven Earth Man (Shanghai)] no. 3 (1936), 60-63. ↩

Ying Xiang 影香, “nianhua yanjiu” 年画研究, “The Study of New Year Picture”]. TianjingShangbao Huakan 田径商报画刊 [Track and Field Commercial Pictorial], vol. 31 no. 28 (1935), 1.) ↩

Lu Xun, Selected Works Volume Four. Trans Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang. (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1980), 39. ↩

Ximin 细民, “shencha nianhua” 审查年画 [“Censor New Year Pictures”]. TianjingShangbao Huakan 田径商报画刊 [Track and Field Commercial Pictorial], vol. 6 no. 21 (1932), 1. ↩

Ximin, 细民, “shencha nianhua(xu)” 审查年画 (续) [Censor New Year Picture (Follow-up)] TianjingShangbao Huakan 田径商报画刊 [Track and Field Commercial Pictorial], vol.6 no. 23(1932), 2. ↩

Ellen Johnston Laing, “Reform, Revolutionary, Political, and Resistance Themes in Chinese Popular Prints, 1900-1940” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, vol. 12 no. 2(2000), 123. ↩

Ellen Johnston Laing, “Reform, Revolutionary, Political, and Resistance Themes in Chinese Popular Prints, 1900-1940” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, vol. 12 no. 2(2000), 134. ↩

Sherman E. Lee, “The Literati Tradition in Chinese Painting” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 108 no.758 (1966), 258. ↩

Wang Shucun, Wang Haixia王树村,王海霞, Ninahua年画 [New Year Picture] (Hangzhou: Zhejian Renmin Publishing House, 2005), 1. ↩

A Ying, 阿英, Zhongguo nianhua fazhan shilue 中国年画发展史略 [A Brief History of the Development of Chinese New Year Picture] (Beijng: Zhaohua meishu Publishing House, 1954), 12. ↩

Cao Shuqin 曹淑勤, zhongguo nianhua 中国年画 [Chinese New Year Picture] (Beijing: zhongguo jianzhu gongye chubanshe, 2009), 24. ↩

Wang Shucun王树村,zhongguo minjian nianhua shilunji中国民间年画史论集 [A Collection of Essays on the History of Chinese Folk New Year Picture] (Tianjin: Tianjin Yangliuqing Huashe Publishing House, 1991), 4. ↩

Zhang Xiumin 张秀民, zhongguo yinshuashi中国印刷史 [The History of Printing in China] (Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin chubanshe, 1989), 654. ↩

Mikhail M. Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World (Bloomington: Indiana University Press,1984), 11-12. ↩

Zhong Fangshi, 仲芳氏,“Gengzi Jishi” 庚子记事 [“The Chronicle of Gengzi”], Gengzi Jishi 庚子记事 [A Chronicle of Gengzi] ed. Zhongguo kexueyuan lishi yanjiusuo disan suo (Beijing: Science Publishing House, 1959), 35. ↩

Yang Diangao 杨典诰, “Gengzi dashiji” 庚子大事记 [“The Memorabilia of Gengzi”], Gengzi Jishi 庚子记事 [A Chronicle of Gengzi] ed. Zhongguo kexueyuan lishi yanjiusuo disan suo (Beijing: Science Publishing House, 1959), 96. ↩

Kay Ann Johnson. Women, the Family and Peasant Revolution in China (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2009), 8-9. ↩

Ke Shi 克士, “cong huazhi jiangdao funv de diwei” 从花纸讲到妇女的地位 [“From New Year Picture to Women’s Status”], Dongfang zazhi 东方杂志 [Orient Magazine], vol.31 no.51 (1934), 4-6. ↩

David Der-wei Wang. Fin-de-siecle Splender: Repressed Modernities of Late Qing Fiction 1848-1911 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997), 59. ↩

Catherine Vance Yeh. Shanghai Love: Courtesans, Intellectuals, and Entertainment Culture, 1850-1910 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006), 4. ↩

Article: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Article Image: Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, "Encode/Decode", 2020. Used with permission from the artist.