Introduction

Much has been written about Explorations: Studies in Culture and Communication (1953-59), the journal founded by Marshall McLuhan and edited by Edmund Carpenter (with a small associate editorial team consisting of McLuhan, W.T. Easterbrook, J. Tyrwhitt and D.C. Williams). The famous run of 9 “ended” with the McLuhan-less “Eskimo” issue (not the last issue of the journal, but simply the end of the original run) that drew upon images and art from filmmaker Robert Flaherty and drawings by artist Frederick Varley. The 1959 issue sans McLuhan was followed by the selection, published the following year by Beacon, and jointly edited by McLuhan and Carpenter, as Explorations in Communication (1960). The first 8 issues are considered by some McLuhan experts to be definitive. Bob Dobbs (2005: 86), for instance, seems to think the Explorations experiment “ran its course until 1957 […] obsolesced by Sputnik on October 4, 1957.”1 Yet for every obsolescence there are, of course, other laws of media simultaneously at work.

Issue 9 published in 1959 marked a pause in the journal’s trajectory and was quite unlike the earlier issues in appearance, size and design, with none of Harley Parker’s design nuances, inserts, and typographic flair. The halcyon days of Explorations had ended as the original funding from the Ford Foundation seminar on Culture and Communication (1953-55) ran out and the Toronto Telegram’s brief sponsorship, courtesy of publisher John Bassett, of issues 7 and 8 in 1957, evaporated. McLuhan refers in passing to Eskimo as the “last issue of Explorations” in a 1969 letter to television talk-show host Jack Paar;2 this letter was written after the Explorations resumed publishing. The original Explorations of the 1950s carries in some instances an incredible intellectual weight, as Philip Marchand insists in describing McLuhan’s final appearance in the journal’s pages:

McLuhan’s final appearance in Explorations, in the October 1957 issue, really caps the intellectual process he had made since the periodical had been launched […] Everything McLuhan said or wrote afterward is directly traceable to something he wrote in the first eight issues of Explorations.3

Douglas Coupland describes the journal as a “glorious stew of diamonds and rhinestones and Fabergé eggs and merde.”4 For Coupland, Explorations was McLuhan’s “calling card throughout the world.” It is against this background of heavy valorization that what I am calling the “unknown” post-life of Explorations takes shape. Its existence has passed without much scholarly commentary. Indeed, some passing mentions of its second-life are without any content, as in Terrence Gordon’s remark: “In 1964 Explorations was revived as a sixteen page insert in the University of Toronto Varsity Graduate magazine for alumni and survived in that format into the 1970s.”5 No longer a stand alone journal, the new Explorations would need assistance to move forward. In fact, McLuhan in his published letters refers a number of times to the return of the journal, but is careful in each case to qualify the event, emphasizing how “small” and “restricted” it is and that it constitutes a “portion” of a larger publication.6

Journalist Robert Fulford, who has been a keen observer of publishing in Toronto for many decades, did, however, devote several paragraphs to the “unknown” years of the journal. He observed that after a few years of quiet from 1959 to 1964, the journal reappeared as an insert in Varsity Graduate, the University of Toronto alumni publication edited by Kenneth S. Edey, Director of the Department of Information, the University’s News Bureau and PR Department. This incarnation ran until 1972 when a note appeared to the effect that, as Fulford describes:

In the issue of May, 1972, at the bottom of his last page, [McLuhan] published the following: “Editor’s Note: Mr. Ken Edey tells me that in all the years that the Explorations series has appeared in the Graduate there has never been a response, pro or con, nor a comment of any sort.” That was his farewell. Could anyone but McLuhan have compressed his thoughts and feelings into such a magnificently deadpan line?7

Not entirely unknown, but apparently unnoticed, Explorations under the editorship of McLuhan alone dissolved in the spring of 1972. It is worth noting that the last 2 issues, after the re-design of the Varsity Graduate (re-christened University of Toronto Graduate), resembled the larger, 8.5 x 11 inch format Issue 9 of 1959 in size and shape, losing the versatility of the Varsity’s smaller scale of 5.5 x 7.5 inches—a magazine within the magazine. At least the final two issues of Explorations in 1972 enjoyed the use of glossy stock, unlike the cheaper newsprint of the broadsheet that it would assume the following year and throughout the 70s. But there is something else afoot here in the laconic tone of McLuhan’s note, the end of Edey’s tenure as editor of the Graduate.

This paper is animated by a number of research questions about the “unknown” years of Explorations, not all of which are purely historical: what were the institutional politics around the publication, and within this complex context, how did McLuhan and Edey work together? Was it really unread by the thousands who received it, and those who subscribed to it for a mere $2.00 per year for four issues? Most importantly, however, is this question: what does this project contribute to the search for new directions in academic publishing? In my professional life outside the academy, I have been inspired by the example of Explorations. In the 1990s, I created and edited a print product called Cyber Scene consisting of Web site reviews for Thomson Central Canada’s newspaper and Internet division that was an insert, designed with a nod to the futurism of The Jetsons, in the colour comics section of the weekend editions of Thomson papers from Thunder Bay to Medicine Hat. While I was trying to reach readers of the funnies, especially younger ones, the question of the unnoticed status of Explorations raises questions about what counts as success and failure in publishing experiments; after all, the magazine within the magazine ran for 8 years and, as I will describe below, was one among several supplements that would fill out and aid the publishing program of the Varsity Graduate. Whereas I had to attract advertising dollars, Explorations experienced no such pressure, although it, too, needed to secure outside support. At some point in the mid-60s, however, the supplements multiplied and lost their secondariness, becoming the main attractions of the Varsity Graduate magazine, even though Explorations must have been continuously haunted by its earlier and more famous incarnation and to whose absence its continued existence attested. It would be appropriate here to consider a logic of the insert in which the Varsity Graduate supersedes its role as bundling device and becomes primarily a magazine defined by its inserts. This ambitious project by editors Edey, McLuhan and others is not merely a theoretical inversion but a provocative institutional practice to whose consequences Edey, and his assistant, were attuned and could not quite carry off. The question of money is not, then, far away, as funding for the supplements was not a supplementary issue.

Institutional Politics

In a number of private, unpublished, letters, McLuhan alerted his friends and colleagues to the re-birth of Explorations. In December 1963, he wrote to the young librarian and friend James Feeley in anticipation: “Things are beginning to develop here at the Centre. Shall put you on the mailing list at once, since Explorations is likely to get started again before too long.” The following summer McLuhan asked: “Have you received the Varsity Grad with Explorations in it?” The small extant correspondence between McLuhan and Feeley indicates a number of salient issues that would emerge with Explorations’ resurfacing, including McLuhan’s efforts at getting Feeley a secure post at the University of Toronto Library (with a recommendation from Father Bernard Black, St Mike’s college librarian). Indeed, in addition to working in the Library’s Order Department, Feeley would become McLuhan’s assistant on all matters relating to the publication of Explorations. By 1966 Feeley was serving as liaison between McLuhan, Edey and University of Toronto Press, often bypassing the Department of Information when necessary – that is, when the prerogatives of public relations threatened Explorations’s “scholarly integrity” or annoyed Professor McLuhan. As sole editor, Explorations was McLuhan’s “baby.”

In the spring of 1966, Kenneth Edey wrote formally a detailed letter to Feeley outlining the terms of reference of the role of McLuhan’s assistant, with a “small honorarium” paid by the Department of Information, but with the clear instruction that the assistant would report only to McLuhan and not to the Department. Given the routine of print production at work in the mid-60s, Feeley’s role typically involved gathering copy, consulting with Harley Parker at the ROM when necessary on graphics matters, which were few; delivering copy to UTP (at that time, Peter Dorn); fielding queries from the typographer, following McLuhan’s advice regarding word counts and editorial issues, and dealing directly with the print shop’s superintendent (at that time, Roy Gurney). Edey described himself as an “innocent cheering section” but assured Feeley that he would deal with any serious political problems should they arise. Feeley’s job would be, Edey admitted, largely a “labour of love.” As the years went on Feeley would in addition fish for contributions, as McLuhan himself would, and write for Explorations (joining a well-known cast, up-and-comers, and family members) as well.

After the first few years the resources available for the publication actually increased. In the following year, 1967, Edey imagined that Explorations, printed by offset in 16-page sets, might double to 32 pages. In late 1966 new money had materialized courtesy of the Associates of the University of Toronto, Inc., the New York-based US alumni organization that sponsored Explorations. In a letter to McLuhan (and Feeley) of August 1967, Edey explained in detail the possibilities: stay with the offset process, but at 32 pages, and retain the coloured paper that was used “to emphasize its separateness;” or, expand the page count but by going to letterpress printing, which would require abandoning the coloured paper and adopting the white coated stock upon which the rest of the VG was printed. Edey suggests adopting a symbol system that would mark Explorations as separate. Although these changes were not adopted, the influx of new money made it possible to imagine a new and improved version. Edey’s enthusiasm for the presence of Explorations in the VG was evident, but couched in institutional terms which themselves were tightly imbricated into the threads of legitimation. He wrote:

the Graduate is a PR publication with none of the scope of freedom of either an academic or general interest periodical. … In this context, the value of Explorations … just cannot be over-stated. With Explorations between our covers as a separate entity we can and do claim magazine-status without danger to the Graduate and its non-tenurized editor. So, in suggesting a little more elbow-room and flexibility for Explorations, we have the Graduate’s interests at heart.

Edey wanted to balance the struggle for scholarly legitimacy with the purely promotional and congratulatory discourse of alumni publications. Explorations mightily assisted Edey to edge the Varsity Graduate into “magazine-status” (beyond its function as point of contact between the institution and its graduates) and seek an audience beyond those who received it for free in virtue of their connection with the university. But Edey also had to be careful to temper his own ambition so that it did not threaten his own position, which did not enjoy the protection and security of tenure. Explorations was not the only valuable property that Edey had at his disposal to enliven and enhance what the Varsity Graduate had to offer.

Interpretive Contexts

Serial publications, specifically journals and magazines, have played a vitally important role in defining the intersecting fields of communications and cultural studies in Canada. Journal publishing helps to create new institutions in which groups can elaborate their projects, and collaborate with fellow travellers. In Canada, Explorations (and later Dew-Line Newsletter) stands as the earliest key resource for investigating the transdisciplinary ambitions of the communication-culture nexus, alongside the even later Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory (1977-91), the Canadian editorial groupings of the American political theory journal Telos (1968-), and its first international conference in 1970 held at the University of Waterloo, as well as Borderlines (1984-1999), the first cultural studies magazine in the country but which had one foot in academic and another in the alternative press. The study of journals involves a multi-methodological approach that combines elements of media archaeology, interviews with former editors and editorial board members, and archival investigations of institutional support systems in and outside of universities, including publishers, presses, associations, granting agencies, and places such as bars and cafés where meetings took place and the institution was “made.” McLuhan scholars have long recognized the significance of the city of Toronto in the early-to-late 1950s, despite its reputation for ugliness and meanness at the time, and the important role played by The Royal Ontario Museum where scholars regularly met over coffee, especially after Harley Parker relocated there as Head of Design and Installation in 1957 (until 1968), as a crucible for McLuhan’s projects. This situation has been described by Janine Marchessault as a “period completely conducive to a journal like Explorations.”8 It was the emergence of an interdisciplinary approach to culture in a city possessed by the spirit of “possibility and creativity” that partook of an international trend in the 1950s that blossomed in Birmingham, Paris, Chicago, constituting the origins of cultural studies, and to which McLuhan himself had already contributed from his post in St. Louis.

The formidable reputation enjoyed by the original run of Explorations in the 1950s, and its international intellectual milieu consisting of companions Roland Barthes’s cultural mythologies, Richard Hoggart’s literary studies, and Reuel Denney’s essays on pop culture spectacles, is is a hard act to follow in the “unknown” issues of 1964-72. First of all, these issues were not stand alone journals, but inserts. Explorations was, as the VG’s table of contents advertised, “a magazine within the magazine.” As the end of the 1960s rolled around, Explorations would remain in place but was identified explicitly as “Marshall McLuhan’s magazine,” and marked as separate by its colour stock (mostly yellow at this time). McLuhan was after all the sole editor, and his exploits were often reported on in the Varsity Graduate itself. The first four years of Explorations, the insert, were also unnumbered. They are embedded in the VG and UTG in the following issues:

- May-Summer 1964 v. 11/2

- December-Christmas 1964 v. 11/3

- April-Spring 1965 v. 11/5

- June-Summer 1965 v. 11/6

- December-Christmas 1965 v. 12/1

- April-Spring 1966 v.12/3

- June-Summer 1966 v.12/4

- December-Christmas 1966 v.13/1

- May-Spring 1967 v. 13/3

- Final VG issue. June-Summer 1967 v.13/4

- UTG begins. December-Christmas 1967 v.1/1

These issues correspond to the numbers 10-20.

In the Graduate of March 1968, v. 1/2, a note appeared on the cover page of Explorations #21 (April 1968):

We have resumed numbering Explorations. The original issues, 1953-59, were numbered 1-9. The issues which appeared in Varsity Graduate from Summer 1964 to Christmas 1967 were not numbered.

This return to a numbering system surfaced at a time when the publication had absorbed other informational University publications and wanted, in addition, to maintain continuity in its presentation of Explorations, all the way back to the original series. This backwards connection to the original imprimatur is a serious intellectual endorsement and legacy issue. It may seem like minor repositioning, but in the domain of serials publishing, continuity is a primary concern. It is useful to think of how the CJPST, the paper publication of which ended in 1991 after 15 volumes had appeared, was “reinvented” 2 years later as online journal Ctheory.org. The original CJPST was subsequently figured as “intellectual foundation” for its online cousin and it is suggested that it may be “read as a sequel to the future.” Arthur and Marilouise Kroker have observed that “issues” of Ctheory are actually continuations of the volume numbers of CJPST.9 In the case of Explorations, continuity is doubly important, at least in historical terms. Firstly, the first issue of Explorations in December 1953 noted that it would be published 3 times per year for 2 years (it was actually published twice in both 1954 and 1955), envisaging a short run, “not as a permanent reference journal that embalms truth.” Second, the question of permanence was always at the forefront of the project, and backwards continuity not only smooths over gaps but stabilizes the legacy, integrating the odd numbers (like issue 9), and dispensing with qualifications about the legitimacy of certain issues (is an issue of Explorations without McLuhan still Explorations?). A newly numbered run of issues stretches, then, from March 1968 v. 1/2 (#21) through June 1971, v. III/5 (#30), with the final two in January and May 1972 volume and issues IV/1- and 2.

All of the numbered and post-numbered issues appeared inside the UTG:

- March 1968 v. 1/2 – Explorations #21

- June 1968 v.1/4 – Explorations #22

- December 1968 v. II/1 – Explorations 23

- March 1969 v. II/2 – Explorations #24

- June 1969 v. II/3 – Explorations #25

- December 1969 v. III/1 – Explorations #26

- April 1970 v. III/2 – Explorations #27

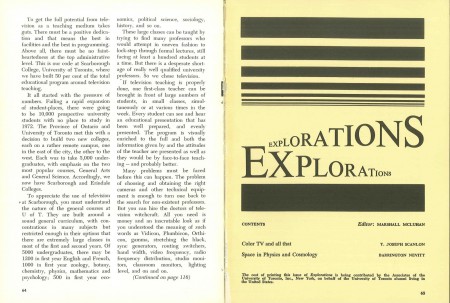

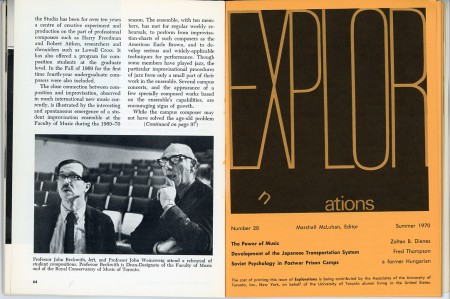

- June 1970 v. III/3 – Explorations #28

- Winter 1970-71 v. III/4 – Explorations #29

- June 1971 v. III/5 – Explorations #30

New, large format:

- January 1972 v. IV/1 and May 1972 v. IV/2.

Yet, the suggestion that there were 32 issues of Explorations is still met by uncomprehending stares.

A Magazine Within

Reviewing the Christmas issue of the Varsity Graduate in 1965 reveals the presence of not one, but two, supplementary inserts. Of the 128 black and white pages of the VG, the Explorations section, on yellow stock, contained two articles (by Sheila Watson and Harley Parker) occupying 16 pages. Another insert, Meeting Place – Journal of the Royal Ontario Museum, under editor W. E. Swinton, was embedded later in the issue and occupied the same number of pages on the same yellow stock, with shorter articles on popular science topics of interest to a natural museum going public – collecting specimens, excavating ruins, etc. Another yellow stock insert actually predates both Explorations and Meeting Place – March 1964’s School of Social Work’s 50th Anniversary Papers. The co-supplements of Explorations and Meeting Place of May 1964 are in some ways perfect bookends to the extent that they are held together by Harley Parker, then Chief of General Exhibition at the ROM, who would join McLuhan for a sabbatical at Fordham University in 1967. His book design and illustration expertise, not to mention camaraderie, was an important ingredient of the men’s friendship and furthered inter-institutional cooperation between the University and the ROM which exists to the present with new ROM Director Janet Carding and the Faculty of Information. Parker, for instance, published articles a number of times in both Explorations and Meeting Place, and his McLuhanesque musings on design and “electronic instantaneity” as a challenge to the disciplinary displays of the museum became a staple of sorts. Adam Lauder’s (2011: 56) recent reminder of Parker’s importance for Canadian design as we approach 20 years since his death in 1992 emphasizes just how “unlikely” his collaboration with McLuhan was, and just how “unconventional” his curatorial principles were, and why it is necessary to revisit his legacy in order “reflect upon the ambivalent meaning of participation in an economy driven by social technologies.”10

First there were two. Then there were three. In 1966, however, a further supplement appeared. Philosopher’s Walk, on its regular green paper. The December 1966 VG contains no less than 3 inserts within its covers, a trend that would continue into the following year. PW was far larger than its fellow journals, extending to some 48 pages of “good talk and good writing.” This magazine took a page from McLuhan’s Explorations in terms of content. For instance, in Explorations of Spring 1965, Glenn Gould’s “Dialogue on the Prospects of Recording” consisted of excerpts from his CBC radio program; likewise, in PW of December 1966, much of the issue consisted of a reprint from a new CBC journal Media 1 of a discussion originally aired on the series “The Human Condition” between Gregory Baum and Northrop Frye. To the inter-institutional cooperation of the University and the ROM can be added the CBC. Of course, much of Philosopher’s Walk was University related, specifically addresses by President Claude Bissell, and reprints from other alumni magazines, for instance, Morley Callaghan’s Doctor of Laws acceptance speech from Columbia University Forum in 1966. For those who don’t know the University of Toronto campus, philosopher’s walk is a pathway that runs north-south between Hoskin and Bloor avenues, between the ROM, Trinity College and the ice rink.

Nestled among the advertisements for professional services and articles about students, faculty, alumni and new buildings, three supplements regularly competed for attention in a very busy and multi-layered alumni magazine. Philosopher’s Walk outlived Meeting Place and was still appearing in 1972! How to explain the longevity of Explorations? The matter is relatively easy. McLuhan’s journal enjoyed the financial support (for printing) of the Associates of the University of Toronto Inc., which acted as a conduit for donations made by alumni living in the United States. A note to this effect first appeared in the VG Dec-Christ. issue of 1966 and continued to Explorations #30. The similarity between Explorations numbers 9, putative numbers 31 and 32, perhaps owes to the fact that they were produced without dedicated funding.

The triple-decker sandwich approach to publishing the Graduate in the mid-sixties was remarkably novel and undeniably ambitious. The effect on the Graduate was to turn it into the newspaper for wrapping the proverbial fish, that is, the supplements were where the action, and the reading, was, and the rest was just, well, alumni relations filler. Yet this filler was also a supplement of sorts because it was, at least for some readers, the juxtaposition of the two disparate kinds of content that impressed itself upon them.

Conclusion

I began this article with reference to Fulford’s quotation of McLuhan’s deadpan comment about the alleged fact that Edey received no feedback about the publication of Explorations during its entire 8 year run. No magazine outside the walls of a University could manage to survive on this basis – perhaps inside as well. The obvious falsehood of this message is attested to by the presence of a photocopy appended to the Edey-McLuhan-Feeley correspondence. A section of the “Commentary” section of the Times Literary Supplement (TLS) from Thursday May 9, 1968 includes the following item:

One of the oddest periodicals to come our way in recent weeks is the University of Toronto’s The Graduate. At first glance it is homely campus reading. […] What, then, is odd about The Graduate? Simply that on page 65 the glossy pages come to an abrupt halt, the academic faces disappear, the simple sentences tail off. We are suddenly plunged into Explorations No 21 edited by Marshall McLuhan, an autonomous inset containing opaque contributions by some of the prophet’s most advanced acolytes. […]

And so on. A long feast of knottily wide-eyed portentousness that will be savoured by media philosophers everywhere. But how unelectronic of Professor McLuhan to hide it away in such an obscure corner. And how cunning of The Graduate’s editor to resume his own chores, on page 97, with a chummy yarn about the college printer whose “hobbies include an old-time printing shop in the basement of his suburban home.”

This cheekily written, anonymous piece (anonymity was the norm for contributors at the TLS during this period), exposes what Edey knew all along: the tension between the desire to become a magazine while undertaking the somewhat banal services provided to the University and its alumni. Between campus homeliness and intellectual respectability, without the heavy apparatuses of footnoting and lengthy citation lists, is a very large gap, but one bridged by the burgeoning inserts. However, Explorations 21, with two articles – Hugh D. Lumsden’s “The Cinema of the Future,” and John W. Abrams’s “Science Technology and the Humanities” – might seem portentous for a reader unfamiliar with the general tone of the publication and of McLuhan’s prophetic vision which he exercised in abundant ways during the late 1960s. These articles were no more or less opaque than any others. Re-embedding Explorations into the linear space of print and the nuts-and-bolts issues of its production as I discussed above was an ironic blow to be sure, and one that underlined the novelty and, to be sure, the obscurity, of the project without expending any effort to extract a positive lesson from it. If we meditate for a moment on one of the authors mentioned above, namely Abrams, we see how his role as participant/contributor changed by the time he joined the Review Committee of the Centre for Culture and Technology in 1980. Abrams noted that McLuhan’s star had imploded and the critical attention he once attracted had all but disappeared.11 The salient question became whether a Centre without McLuhan was a viable entity within the University.

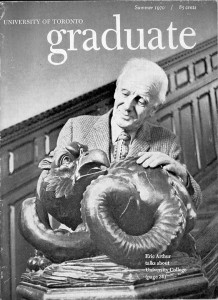

Explorations, the insert, had a cover page consisting of a title with letters of diminishing size running right to left and left to right, the table of contents below, a format designed by Harold Kurschenska who had by left U of T Press shortly after the magazine really got rolling. It was a simple and clean design which would survive until a redesign in June 1970 created a cover with enormous letters “EXPLOR” below which “ations” was found along with a floating “n.” Yellow stock gave way to orange and purple. For the most part, Explorations was all text with few exceptions and little typographic adventure in its pages. Edey oversaw and “cheered” the entire run from a distance. Indeed, his career trajectory was impressive in its own right – he first appeared on the masthead of the VG in September 1959 and was named as editor in December, replacing C. G. M. Grier. His run continued to 1973 when Lawrence F. Jones became editor of the Graduate in its broadsheet format with more contemporary content from around campus.

The early 1970s saw the end of the Bissell Presidency, waning of the McLuhan mystique, increasingly frosty relations between McLuhan’s Centre for Culture and Technology and the Graduate School, and a growing focus on social movements. McLuhan’s experiments in publishing were, in many ways, easy targets for media wags both near and far. Journalist Graham Fraser (1968) wrote in the Toronto Daily Star about the DEW-LINE Newsletter in a mocking tone, comparing it to Dale Carnegie and Charles Atlas adverts, an act of pure hucksterism. Graham complained that the newsletter contained “very little new McLuhan,” was overpriced at $50/yr subscription, and ended his tirade with: “Finally we have come full circle. The cultural archaeologist has become a cultural artifact.” Coupland refers to DEW-LINE as “repurposed McLuhanalia.”12Explorations, too, would run more and more excerpts as it aged (ie., from Executive as Drop-Out), course papers, students reports, and recycled letters to the editor; it outlasted DEW-LINE by two years.

The insert as welcoming gesture of support during a period of significant reductions in arts funding is not a cultural commonplace but a known quantity. In 1993, after 10 years of publishing, the contemporary Canadian literary magazine Rampike published its first supplement in Border/lines #28. Emphasizing the “modesty” of the first issue, editors Jim Francis, Karl Jirgens and Carole Turner look forward to a new readership in the cultural studies milieu that straddled the academy and the alternative press world of downtown Toronto. While Border/lines did not regularly publish fiction, it welcomed the addition of high quality new writing by figures such as Misha Chocholak and Diane Schoemperlen. In 1994, Border/lines was celebrating its 10th anniversary, and Rampike was placing its third supplement, which was joined by another supplement of photographs of site specific artworks placed on benches courtesy of the Vancouver Association for Noncommercial Culture. This short-lived alliance with Rampike was superseded by a generic “Literary Corner” edited by English professor Stan Fogel that ran regularly throughout the later years of the magazine in the late 90s. However, the insert as a gesture of solidarity and helping hand for a fellow traveler best defined the Rampike partnership, and the opening it created for greater fictional and art and text experimentation suited the growing graphical heterogeneity of the magazine and literary spirit of its editorial board. Border/lines’ era of supplementarity was, however, short and sweet.

The ambition of Edey to double the length of Explorations went unrealized. Instead, he multiplied 16-page inserts and in this way introduced diverse kinds of writing into the magazine that otherwise would have had no place among the campus reportage, smiling and/or serious faces of decision-makers and movers and shakers – all the good news and “excellence” of alumni discourse. The inter-institutional relationships cemented in the process strengthened his management of University publicity in the city, and perhaps even abroad through the New York sponsorship, and his wielding of the McLuhan brand was masterful and protective, even if evidence of what might count as success, critical or otherwise, was a bit scant.

The inclusion of “magazines within” did not help to sell the Graduate as it did not have a presence on the magazine racks. Rather, it capitalized on the title Explorations and extended its legacy, perhaps not as a “calling card” but as a continuous platform for McLuhan and his associates to expand their sphere of influence. The fact that Explorations did not stand alone but needed to be carried, despite a concerted effort to turn the logic of the insert on its head, caught it up in a multiplex supplementarity that it did not ultimately dominate by, for instance, outlasting the Graduate, or freeing itself from its binding. By 1972 this play had run its course. And, as the Border/lines example suggests, even a more short-lived version of inserts such as Rampike – initially described in hopeful terms as a “pull-out” to indicate separability and independence – must struggle to open a crack in the container within which they sit and to which they owe their continued existence. Editorial change at the Graduate proved decisive: the supplement would not become that dangerous.

Yet, as filling rather than filler, the insertion of Explorations on its coloured stock in the black and white Graduate, was certainly more hearty than the notes and quotes and achievements in leadership among the University administration. Playing on this juxtaposition gave Explorations, more than Meeting Place and Philosopher’s Walk, a contemporary feel and provided energy for a much-needed expansion of scope beyond the dictates of public relations. Although the migration from print to online is today a well-trodden path for academic journal publishing, Explorations can contribute little to understanding this movement as it stayed within the print universe; it was beholden to the offset process. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine a hybrid format of any kind, either Explorations or indeed Border/lines with a less academic and more public orientation, knowingly searching out opportunities to publish in alumni magazines (whose relevance in in the era of social media is always on the table) while investigating ways of transferring knowledge to one or more publics or stakeholders. The generation of messages for internal and external consumption by the previously converted or at least currently employed has little in common with the interests pursued by McLuhan, his colleagues and students. This was surely the point: not to adopt the conventions of the Graduate, but to surmount them; to search for a wider audience and attempt to reach it—a captive or pre-made one at that consisting of graduates—but with none of the doctrinal attention to disciplines and divisions of knowledge that the university enshrines in its institutional organigrammes of power/knowledge: department/faculty/division/school; pure/applied; social/hard etc. And, in remounting Explorations as an insert, the messy interdisciplinary of the project was again underlined.

Nevertheless, Explorations only hinted at intermediality, in the sense that it remained inter-medial within the universe of print, while playing with lineality to some degree, mixing papers and layout, distributing its signifiers of separateness. It did not accede to multiple forms of media of representation, unlike McLuhan’s DEW-LINE Newsletter, which combined diverse publishing formats with playing cards, slides, posters, etc. To the degree that Explorations was a filling of substance with signifiers of separateness, it deployed contrast within a limited field in order to evoke, rather than to deliver, different modalities of sensory experience. The anonymous reviewer in the TLS was right: “plunging” into Explorations in the Graduate was both a shock and yet very unelectronic, or non-acoustic space-like, and not at all multi-mediatic. Yet, advanced examples of non-standardized publishing were the death knell of the DEW-LINE Newsletter: the production costs were prohibitive, despite the significant revenue generated by some 4000 subscribers after the first year. Moreover, neither Explorations or DEW-LINE were credentializing publications for their editor and writers since they were one man shows without peer review and combined with other interests from the business and promotional worlds.

The funding arrangements for Explorations throughout its life-span were significant: today, we look for diverse revenue streams beyond the federal and provincial governmental granting agencies because money from foundations, for instance, provides more flexibility for the researcher. McLuhan certainly pioneered this practice in seeking support first from the Ford Foundation in 1953, and then from newspaper publisher Bassett who gave $7000 to publish two issues of Explorations in the late 50s; later, through Edey’s best offices, a US-U of T alumni group supported Explorations from approximately 1966-71. Edey also arranged for an honorarium to be paid to an assistant for McLuhan. As McLuhan surmised in the early 1950s, the future of academic publishing would rely on heterogeneous revenue streams originating from sources outside of the professional associations and granting agencies; instead, he sought out funding opportunities arising from the inter-institutional arrangements between the university sector and the foundations, corporate media (print and television) and even the public relations department of his home institution and its alumni branches. Although some of the results were short-lived and disappointing, such as DEW-LINE and the entrepreneurial practices of its publisher Eugene M. Schwartz, President of the Human Development Corporation, other arrangements were simpler and less risky, while promoting sales. For instance, during the formative years of Toronto Life magazine, a copy of the McLuhan and Fiore book The Medium is the Massage was given away with every new subscription in the fall of 1967. McLuhan’s desire to reach beyond the walls of the ivory tower, to connect with wider non-specialist publics, without becoming dependent on agency funding, yet generating it through novel inter-institutional arrangements, constitutes a valuable legacy in its own right and delivers a lesson about survival tactics for any new publication with similar ambitions.

Bob Dobbs, “McLuhan and Holeopathic Quadrophrenia,” in The Legacy of McLuhan, eds. L. Strate, E. Wachtel (Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press, 2005), 86. ↩

Marshal McLuhan, Letters, ed. M. Molinaro, C. McLuhan and W. Toye (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1987), 350. ↩

Philip Marchand, Marshall McLuhan: The Medium and the Messenger (Toronto: Random House, 1989), 133. ↩

Douglas Coupland, Marshall McLuhan: You Know Nothing of My Work! (New York: Atlas & Co., 2010), 123. ↩

Terrence Gordon, Marshall McLuhan: Escape into Understanding (Toronto: Stoddart, 1977), 162. ↩

See McLuhan, Letters: 382, 316, 301, 304. ↩

Robert Fulford, “All Ignorance is Motivated: Re-examining the Seedbed of McLuhanism,” in Marshall McLuhan: Critical Evaluations in Cultural Theory, Vol. 1, ed. G. Genosko (London and New York: Routledge, 1991), 315. ↩

Janine Marchessault, Marshall McLuhan: Cosmic Media (London: Sage, 2005), 81. ↩

Gary Genosko and A & M Kroker, Unpublished interview at PACTAC, University of Victoria, 2003. ↩

Adam Lauder, “Harley Parker: Design for ‘a new ordering’” (Toronto: Hunter and Cook, no. 9, Summer 2011), 56. ↩

Minutes of the Review Committee of the Centre for Culture & Technology (April 28, 1980), University of Toronto Archives. ↩

Coupland, Marshall McLuhan, 169. ↩

Article: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Image: “Steel”

Original Artist: Boris Artzybasheff

Flickr: x-ray delta one [James Vaughn]

Url: http://www.flickr.com/photos/x-ray_delta_one

Access Date: 16 January 2013

License: Creative Commons Share Alike