-

1. Does anybody know what the form of a poem is?

-

2. What is the form of a past poem we agree to admire?

-

3. What is the form of a modern poem we agree has changed the world?

-

4. What is the form most indigenous to contemporary poetry?

-

5. What poet has written most newly?

-

6. What do you want to find out?

—Bernadette Mayer, “Twenty Questions about Form or New Forms”1

In her 2002 book Commons, Myung Mi Kim writes that “The lyric undertakes the task of deciphering and embodying a ‘particularizable’ prosody of one’s living.”2 On its face, Kim’s remarks rehearse a critical commonplace: that lyric enables the expression of discretely individual life, distinct from the social or political structures that enable that expression. The distinction between individual expression and something called “the social” or “the cultural” or “the political” has been central to much of the critical discourse about lyric: poems that purport to convey the particular speech of a particular I, speech carved from what surrounds it, are recognizable as lyric because they participate in a structure of address that is supposedly particular and particularizable. That address is, however fallaciously, understood to be “private” according to the logic of lyric reading (that this privacy is a fallacy is one of Virginia Jackson’s central claims in Dickinson’s Misery).3 Yet by characterizing living itself as an instance of prosody, Kim does something different with the particularizability of lyric. Kim frames lyric as the expression of personal and social form, one whose expressive particularizability is both established and destabilized by a pair of quotation marks around the word “particularizable.” Commons – a book which takes its title from the very notion of the social – describes the poem as able “To probe the terms under which we denote, participate in, and speak of cultural and human practices.”4 One’s life may be particularizable, but that particularizability hinges on a prosody that is social. Life is a kind of prosody, so lyric prosody is a social form.

The field of lyric studies has pushed back against essentialist and exceptionalist theories of the self, recalibrating the links between materiality and the subject. New studies of lyric have also coincided with a return to genre critique in literary studies and renewed debates around identity and the status of the literary, and lyric studies’ emphasis on historicization has further coincided with efforts to expand the spatial and temporal boundaries of modernism and rethink periodization.5 Lyric studies’ major contribution has been to reveal lyric not as a transhistorical genre of private expression but, rather, as a historical practice of reading that equates the private speaker with the transcendent one, what Jackson describes as “the voice that speaks to no one and therefore to all of us.”6 Yet in part because its archive tends toward the nineteenth century, lyric studies has had less to say about reading practices or subjectivities in modern and contemporary poetry, despite the many poets whose work engages with the practices of lyric reading and lyric ideology.

One such contemporary poet is Bernadette Mayer, whose site-specific procedural texts constrain and animate the expressive and cognitive textures of the speaking I, complicating the question of what is “particularizable” about lyric expression. In their prescriptive qualities, their ambivalent posture toward authorial intention and embodiment, and their animation of the expressive capacities of built environments, site-specific procedural texts like Mayer’s enact Kim’s “prosody of living.” Mayer’s 1971 work Memory investigates not only the complexities of first-person expression in poetic and visual forms but also the apparent hermeticism of the individual mind. The radically inclusive documentary practices of Memory, followed decades later by the polyvocal and synaesthetic poetics of 2019’s Poems (in Color), constitute two instances of procedural poetics alert to the prosody of living—and to how its lyric expression can be understood as a social form.

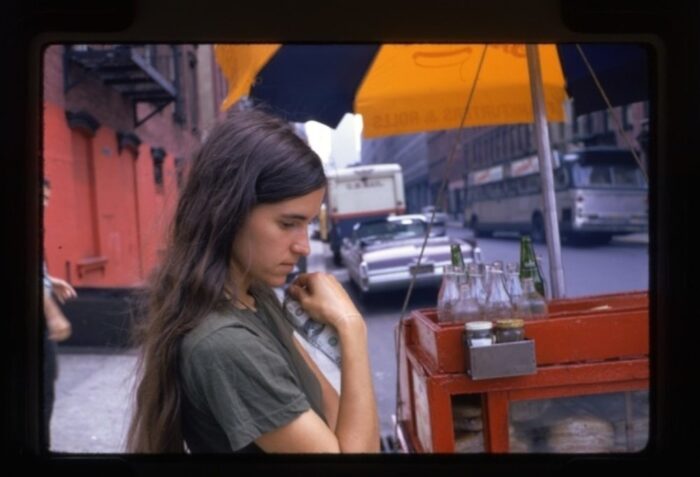

Fig. 1: Photograph from the 1971 Memory installation. Courtesy of Bernadette Mayer Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of California, San Diego. Via BOMB magazine.

When she debuted Memory in 1972 as an installation at Holly Solomon’s 98 Greene Street gallery, Mayer is said to have “burst onto the New York performance art scene” in such a way that fused text-based poetic practice with the conceptual and performative work being done by visual and performance artists at that time.7 To produce the installation, Mayer shot an entire roll of film each day during the month of July 1971, hung the photographs in the gallery, and then used her photographs to record and play back a seven-hour lecture. The audio lecture narrates the events surrounding the photographs, comments on the photographs themselves, and describes Mayer’s intervening dreams on each day. The lecture – just over three hours of which are available as streaming audio at the Bernadette Mayer Papers, Special Collections and Archives, at the University of California, San Diego – functions both as a documentary daybook and as an improvisational, digressive, associative poetic text. Writing in her 1974 book Studying Hunger, Mayer describes the mechanics of Memory this way:

MEMORY was 1200 color snapshots, 3 x 5, processed by Kodak plus 7 hours of taped narration. I had shot one roll of 35-mm color film every day for the month of July, 1971. The pictures were mounted side by side in row after row along a long wall, each line to be read from left to right, 36 feet by 4 feet. All the images made each day were included, in sequence, along with a 31-part tape, which took the pictures as points of focus, one by one & as taking-off points for digression, filling in the spaces between.8

Memory was the first large-scale project to realize Mayer’s investment in recording dailiness in order to discover how it engenders both sequence and digression. Encyclopedic in its inclusion of daily detail, the gallery installation was also world-making in its immersive qualities. At the same time, the interplay of text and image registers a basic problem in that world-making: in its use of the photographic image as mnemonic compositional tool, Memory’s text is never fully deictic, evincing a gap between the impulse to describe and the capacity to render memory narratively and conceptually legible. Lytle Shaw has noted that the gaps in Mayer’s text, moments when Mayer cannot describe what the audience is seeing, both “distance us from the photographs” – emptying them of their signification for the audience – and “emphasize the complex temporality that Mayer’s project establishes.”9

Fig. 2: Memory, gallery photograph from Bernadette Mayer’s website.

Is Mayer’s text lyric? Is Mayer a lyric poet? Or is there a different question at work here, one about how Mayer’s work illuminates something about the definition of lyric? Mayer is a poet who, in works that followed Memory, pushed the boundaries of the sonnet past its breaking point (1989’s Sonnets, which Juliana Spahr has written “refigure lyric intimacy as collective and connective spaces”); whose work in short “lyric” forms earned her, in her own words, the label of “failed experimentalist” (1976’s Poetry and 1978’s The Golden Book of Words); whose wry allusions to ballad, sonnet, and odic forms are torqued by intertextuality, epistolarity, and an ongoing investment in the expansive durational methods of the long poem, often in the same work (see the mixed forms of 1982’s Midwinter Day or 1994’s The Desires of Mothers to Please Others in Letters).10 Critical reception of Mayer has emphasized the way her work challenges or undoes the notion of a lyric I who orders and limits experience.11 Many of Mayer’s works commit to time-based procedures that draw on abstract associative or spontaneous expressive tonalities. Yet they also use the speaking I as a recurrent formal gesture. In its insistence on the expressions of a first person whose links to visual cues are halting or fractured, Memory formalizes and aestheticizes what might otherwise be read as the hermetic vernacular of first-person expression. If Kim characterizes lyric as the prosody of living, Mayer’s Memory suggests a procedural lyric as the prosody of duration.

Mayer’s uses of the I in her procedural work can also be understood to negotiate what Mayer has identified as two differential strands of her relationship to her literary forbears’ lyricism. In a 1980 letter to Alice Notley, Mayer shares a childhood memory of learning two short poems in the classroom, William Carlos Williams’s “The Red Wheelbarrow” and Emily Dickinson’s “I’m nobody! Who are you?,” as contrasting visions of poetic expression:

Then again there is the question of “The Red Wheelbarrow” or does it even have a title? so much depends upon, and so on … It was written on the blackboard when I was in high school and I can still see it and recite it much the same as I can do with Emily Dickinson’s “I’m nobody who are you …” but somehow, as I’ve made these two poems be opposites, I associate the one, the wheelbarrow of course, with all my ideas and instigations and inspirations to write poetry and the other, the being nobody, with all the Catholic teachings on humility which might actually prevent that from happening.12

Williams signals imaginative possibility, while Dickinson stands for humility, restraint, and possibly even failure. As the central figure of a US poetic tradition that defines “lyric” as poetry onto which readers project a fantasy of restrained private utterance, Dickinson here is cast as the figure of limitation (Mayer’s gesture certainly feels a bit like lyric reading). Mayer gestures toward these contrasting versions of lyric when she writes about the capacity for a poetry whose world lacks a discrete speaking subject:

So that it always seemed to me from Williams I could deduct that the wonderful capacity for the world to exist without an I was good for me and that the rest of a person’s studies of him or her self ought to be relegated to prose which I later noticed he had sort of done too.

Dickinson has been relegated to the hermetic world of subjective poetic speech, a world like Catholic school, while Williams dwells in possibility.

The irony is that the radically inclusive Memory, which bears the marks of Steinian repetition and thought-based language experiments as well as a Williamsesque fidelity to everyday detail and American vernacular, negotiates Mayer’s ability to spotlight and even “study” the self. Mayer described Memory as an “emotional science project” in which its “data” is run through a number of forms and experiments.13 In its chief constraint – the aim to record daily experience for a full month, a unit of time that invites investigations into duration and segmentation – the effect of Memory is a sort of poetry in real time, as a film shot in narratological real time draws attention to minute particulars. In choosing a month to shape Memory, Mayer suggests the synodic phase of the moon, and the integration of dream into her proceduralism frames her uses of the first person as an experiment in narratology. It is not hard to speculate that Mayer had in mind Freud’s argument in The Interpretation of Dreams that the dream, even when forgotten upon waking, modifies waking life through visual and auditory images.14 Leslie Scalapino echoes Freud in describing how the dream modifies waking life in Mayer’s long poem Midwinter Day under the rubric of fiction, which Scalapino by implication defines as perceived reality: “[A]s you become aware of dreaming and that you’re creating fictions, that begins to change the fiction that you have already created.”15

Mayer’s “study” of the self is anticipated by the anti-authorial impulses of one of her earliest writings, “Experiments,” which originated in her early 1970s workshops at the St. Mark’s Poetry Project in New York, workshops which were attended between 1971 and 1975 by early practitioners of what came to be known as Language writing, including Charles Bernstein and Bruce Andrews. “Experiments” was collaboratively revised over the years, and was published in 1984 in Bernstein and Andrews’s The L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Book. An excerpt reads:

Systematically eliminate the use of certain kinds of words or phrases from a piece of writing, either your own or someone else’s, for example, eliminate all adjectives or all words beginning with ‘s’ from Shakespeare’s sonnets.

Systematically derange the language, for example, write a work consisting only of prepositional phrases, or, add a gerundive to every line of an already existing piece of prose or poetry, etc.

Rewrite someone else’s writing. Maybe someone formidable. […]

Experiment with theft & plagiarism in any form that occurs to you.16

Mayer calls for textual acts that upset both canonicity (rewrite someone formidable) and language (derange vocabulary and syntax); “Experiments” resists the determinism of poetic lineage and suggests the radical subjectivity of homage-based writing. It attacks literary authority, questioning established notions of the canonical and the marginal. Moreover, it foregrounds procedure over artifact, textuality over organizing consciousness, and collaborative authorship over individual poetic speech.17 Mayer ends the list, notoriously, with the exhortation: “Work your ass off to change the language & dont ever get famous.”18 Kane uses these last four words (adding a somewhat domesticating apostrophe to the first) as the title of his 2006 anthology Don’t Ever Get Famous: Essays on New York Writing after the New York School, and Mayer’s “Experiments” have come to function as a de facto foundational text for Language writing.19

Mayer’s investments in proceduralism developed early in what Lytle Shaw has described as a commitment to the scientific site as a textual genre. Shaw argues that Mayer as well as one of her earliest collaborators, Clark Coolidge, may be identified with an art historical shift to the site within postminimalism, to the “would-be neutral, non-aesthetic, ‘objective’ language of photographic and textual documentation that so many conceptualists turned to in the late 1960s.”20 Mayer and Coolidge, Shaw writes, treat the book “as context or site,” not as an object but “as a discrete conceptual project, with its own vocabularies and formal structures, with its own self-imposed research methods and goals.”21 The poets’ scientific excursions center on the first person: in these experiments, “the object of study is oneself,” as Shaw puts it.22 Mayer’s description of Memory as an “emotional science project” that scrutinizes both the dream and waking life is anticipated by what she writes in The Art of Science Writing, a teacher’s manual she coauthored with Dale Worsley. There Mayer describes writing experiments that can be used in the science classroom to bring out “the inspired, intuitive, and associative side of the mind.”23 Mayer includes a section on “Dream writing for problem solving” in which the method is both “amusing” and genuinely instructive: “The dreams can be turned into narratives, essays, equations, charts, diagrams, science fiction stories, or any form of writing that seems to reflect the dream, including the entirely speculative.”24

Elsewhere, Mayer warns her students not to go “too far” with experimental proceduralism. She includes Joyce on a list of “writers and scientists” to keep in mind while pursuing the long poem (the list includes Whitman, Burroughs, Coolidge, Stein, and Lacan), following with a qualification: “Joyce was accused of being unintelligible & he was presenting only one level of cerebral events: conscious sub-vocal speech. I think it is possible to create multilevel events & characters that a reader could comprehend with his entire organic being.”25 She then describes Finnegans Wake as an example of the “trap” of experimental writing: “It’s simply if you go too far in one direction, you can never get back & you’re out there in complete isolation, like this anthropologist who spent the last 20 years of his life on the sweet potato controversy (which way it floated).”26 While Mayer throughout her career has championed anti-institutional writing practices that coopt, plagiarize, or otherwise appropriate texts – “Owning language is a weird phenomenon that makes less sense now than it ever did,” she said in 2001 – her critique of opaque proceduralism also indicates an interest in recovering the first-person lyric as an avant-garde impulse.27 In Memory, Mayer suggests, dream collects data for the poetic experiment: “Cause memory & the process of remembering of seeing what’s in sight, what’s data, what comes in for a while.” Dream becomes a way to structure the self: “to you past structure is backwards, you forget, you remember the past backwards & forget.”28

Fig. 3: Memory, North Atlantic Books edition, 1975, available at the Eclipse archive.

Self-centered proceduralism also enables Mayer to launch a critique of gendered modes of subjectivity. In an essay on Mayer and Acconci’s magazine 0-9, Linda Russo argues that Mayer and Hannah Weiner used early proceduralism to question models of “gender, self, writing and form” they saw at work in the community around the Poetry Project, and that their procedural poetics confronted that immediate literary environment as well as social institutions at large.29 Russo cites Mayer’s first published documentary poem text, “Definitions at the center of the Newspaper, June 13, 1969,” as an example of how Mayer uses procedure to investigate the relationship between material text and social acts:

“Definitions” is a verbal map of a constricted reading of the newspaper. Each line describes what is encountered at the center of each page and “defines” it if possible. At times note is made of “the empty space next to a word,” recalling the material through which the news is disseminated. […] A range of objects is invoked: a bridal veil, a man’s beach jacket, an air-conditioner, a piano, the skirt of a dress, the back end of a convertible car, a dish, a map, a sash, an oil tank being used as a lunch box, soap bubbles, a graduation gown, a house door, grass, a plant, the left eyebrow of Joanne Woodward. By re-assembling the objects and icons of consumer culture, this investigation reports on the social body constructed and reflected in these pages.30

As Russo notes, the list in conceptual writing draws on a tactic that was particularly popular among poets of the New York School.31 Yet whereas writers such as Anne Waldman or Joe Brainard use the list to organize items along a theme, Mayer uses the list “to instill disorder.” More importantly, Russo says, Mayer’s performance-oriented conceptual poetics was at its historical moment a specifically feminist response to the models of writing established by the Poetry Project avant-garde.32

Memory debuted as a gallery installation but has had several afterlives in installation and bound and digital text. The written text of Memory, which became Mayer’s fifth book, was published in 1975 by North Atlantic Books in Plainfield, Vermont, and remains out of print. Because Mayer was unable to persuade her publisher to reproduce photographs from the Memory installation, the North Atlantic edition reproduces only the text from the lecture and a collage of just seven photographs on the paperback’s cover. The 1975 edition of Memory, then, removes the written text even further from its photographic moorings. What remains is a massive text of recorded experience that uses the dream to confront first-person lyric speech. It was only in 2016 and 2017, when the Poetry Foundation in Chicago and Canada Gallery in New York launched installations of the original 1971 project, that audiences again had access to the visuals. A facsimile and a reading copy live online at the small press Eclipse archive (edited by Craig Dworkin), and 2020, Siglio Press released a full-color bound publication made from scans of almost 1,150 images from the original project, including some images that were not originally shown in 1972, along with the full text.

The stripped-down text of North Atlantic’s 1975 edition of Memory is organized by dated entries for each day in July. For the most part, the text is written in giant prose blocks that describe or chronicle the movements of Mayer and her circle of friends around New York and the surrounding areas: what they eat; what they buy to eat; where they go on the subway or in the car; conversations about movies, music, books, poetry readings, or social gossip; and so on. Apart from a few sections written in verse, Memory is laid out in blocks of prose. The opening pages of Memory can be read, almost entirely, as alternating lines of two different poems; it’s somewhat startling when Mayer abandons this approach for the rest of the book’s 195 pages. Mayer’s Steinian repetition both defamiliarizes and reassembles these quotidian details, which amass in such volume that the prose blocks are exceedingly difficult to read straight through. Take for example this passage from July 11:

This is Kathleen this is kathleen here is kathleen here is kathleen kathleen is here she’s doing the dishes why is kathleen doing the dishes why is she doing the dishes why the dishes why not the dishes Kathleen doing the dishes she does them she did them last week she did them again she didnt do them right the first time why does she have to do them again do them again, she said. I’ll do them again there she is doing the dishes again look at her doing them she does them typewriter teletape tickertape typewriter tickertape teletape kathleen is doing the dishes she’s doing them again when will she finish when will she finish. (72)

Mayer uses the text to narrate the photograph but then immediately destabilizes that descriptive function: either we are (in the original gallery installation) seeing multiple photographs of Kathleen, or the narration mimics the repetitive motion of dishwashing. But the text then degrades into an obsessive focus on its own mechanistic qualities that muddles into wordplay – “typewriter teletape tickertape typewriter.”

Memory opens on July 1 by suggesting its proceduralism makes possible a new kind of syntax, a new kind of communication via the image: “& the main thing is we begin with a white sink a whole new language is a temptation” (7). (The image of the white sink is one of the few photographs to appear on the cover of the North Atlantic Books edition.) It is a consciously visual language – “we are now in an image” (7) – as well one that uses the visual field to revise memory: “you start it all over this has happened before / list the years / pretty picture of memory noise technicolor sometimes memory / is noise” (13). Noise, for in fact sometimes the memory is synaesthetic, as when it confuses the senses of contact: “we dont hear images from you anymore” (14). The book occasionally acknowledges conceptualism as the genre or tradition in which it participates by fine tuning words and phrasing:

Dinners I’m supposed to go to dinner I already went I go again & again in long addresses in long dresses, tom, we take acid before a dinner & then lose track, or, take acid before a dinner then lose track, somebody’s father, strait-laced I’m strait & laced in long dresses my camera with me, the gas man comes he says this is a conceptual piece lacking conceptual data & he says I got no expectations (100)

As in the wordplay of the “Kathleen” sequence, here the transition from “strait-laced” to “I am strait” (or possibly “straight”) is sequentially associative, but when the gas man steps in as art critic, we appear to be in the realm of dream, in which memory loops back. At the same time, the book also suggests its procedure flattens the value of experience:

July 9

What’s the difference who’s in charge: when our experience is increased by the addition of observations which were future, down the road & reflections to infinity, but are now past, we seek once more to order in the same manner our increased volume of experience: when it’s this bright it’s just as well to look at them small, how, can you see that? But in this increased volume all experience is of equal value, that which was future, reflections to infinity, is in no way different from that which was past, for all is now past (55-56)

Recalling her observation that the experiment can go “too far,” Mayer suggests that all experience may have become equivalent in Memory. Or it may merely be a dry observation, rather than a qualification of the impulses or outcome of her work.

When Mayer narrates the process of putting Memory together, she indicates the way the repetitive operations of sifting through her material for the project can lead to incessant and circular dismantling:

ed left the city this morning to pick up the stuff as I might be able to recreate later recreate later from this & in my mind I would re-argue reascend reassemble & there was a reassembly & I would reassert & there was a reassertion & I would reassess reassign reassimilate, there was a reassimilation & I would reassume & there was a reassumption & I would reattach & there was a reattachment & I would reattack reattempt reawaken rebloom & I would reblossom reboil rebuild & something was rebuilt & I would rebury. (60)

The only thing missing here is the object: Mayer’s text does not specify (here) what is being re-argued, reascended, reassembled, reasserted, reassessed, reassimilated, reattached, and so forth. Unless that thing is the self: the primary object in this paragraph is the ‘I.’ Mayer suggests repetitive actions as the cyclical operations of the subject, who continues to “rebloom” and be “rebuilt” only to be “reburied” – submerged under the masses of quotidian detail. For the gallery installation, Mayer assembled her photographs, then used the lecture to reassemble the events as filtered through her own conscious memory and scenes from a remembered unconscious realm, further textualizing the already palimpsestic nature of experience in this documentary recreation.

Mayer suggests that gaps in memory add to the cyclical and interrupted quality of this processed subjecthood. Memory has its limits: “that’s the extent of memory, I caught it, I caught up with it” (67). On July 10, addressing either a specific reader or a generalized “you,” Mayer signals the reader’s agency in assimilating first-person information and making it aesthetically coherent:

I make a design writing this & later I make something this time out of remembering but later out of not remembering or doing it backwards including hallucinations & all liquid clear distillations of what is it? ice as if you try to remember by will & a choice is here the instant you do: I’ll remember the instant, you dont have to you dont have to remember not memory but snap beyond “the past is so dead for me I have no way of checking on it” (70)

Like perspectival memory, the photographs, too, can’t always be trusted to represent a stable image: “the pictures are like all pictures are lie like sleepers like a railroad crossing sign is a skull” (47). The pictures are also “guileless” (138). The pictures both reconstruct memory and mirror the way experience is remembered visually, but they also continually destabilize representation.

Memory uses dreams to rehearse and expand the field of immediate private perception. Often dreams appear as discrete bits of experience: a dream about eating a specific food or a dream about a particular object seen while traveling. Or dreams are fanciful: “I dream of ed’s parents like vitamins” (49). Or portentous: “words can sink a ship in the shallows reform so dry a crease & saw the same crack in the dream before sink down broad ship at dawn home plate they hold it up to their ears to hear we years you go on” (50). On July 7, we learn that the dreams are within the field of conscious thought: “dreams that ring in your ear” (46). On July 3, Mayer uses the dream to add epic texture to the poem:

No I know we didnt know yet no & new: or: monday to friday – he described the fall of his native – at the hands of the – after a ten year seige telling how the armed – had entered the city in the belly of a great wooden horse & how the – had fled from their burning city among them – & his father – & young – not long afterward – had advised setting sail for distant lands blown by varying winds we quickly – the next day – again on the shores – finally they reached – again the – a hero – in a dream he – when – warned in a dream – decreed that the body – led his band – of the world & the question was how to tell you in a way you’d remember (19)

Citing The Iliad as a dreamlike remembered text as well as the dream at the center of Homer’s epic narrative, Mayer suggests that the dream might have similarly prophetic properties in her text. But this intertextuality also destabilizes the perspectival expectations of the dream itself: the dream becomes a kind of quasi-fiction and converts Memory’s documentary impulses into fictional ones.

Mayer eventually suggests this destabilization of conscious memory as a kind of narrative like a “crime” in which the dream serves as forensic tool. The word “crime” also implicates the reader as voyeur, or as participant in the recreation of something out of bounds:

July 11

You can see that the question I started out from has been almost completely left out by now: I go to a place where you cannot reach me or you go to a place where I cannot reach you, no one can reach you I am alone & you are examining, I can finally tell you that you are examining the reenactment of the crime the reenactment of the crime, to see what it suggests for the future, for future experience, I can tell you this much—there are places, different spots, to move between. The crime’s already done so you can fool around. The photographer comes with us to the scene, with us what does that mean? etc. (71-72)

Ten pages later, it becomes clear that the “crimes” here range from the serious to the banal: arson, hit and run, masturbation, a fight with a friend, an illness. Mayer acknowledges the banality of much of this detail: “we were bored alot of the time” (162); “its boring for words & it’s also anger” (170). The “diary” of Memory not only reconstructs events like these but alters them:

the arsonist a hit & run, I saw it all at once tonight that words are leading me on, the ones in imagination, saw, in leaks in indian leaks somehow, I can erase I can modify I pick up, least it’s not a nautical sleep affinity for words like genet some flow to stretch, stretch out & pull in, to masturbate: & it is in honor of these crimes that I am writing this book & so on, not a use or a function like V., perform a service, work words into a system, words put in a system, its some play, some death, nautical, at sea with them & I started to write that, what’s put in, watts, what’s put in creating problems (81)

And the text itself continues to reach for truth value:

I would never do this again, said in the house as a kind of warning. & as I write all this stuff down I now it comes out of nowhere goes nowhere & remains, nothing leaves. It’s almost a truth. (142)

While the ultimate stakes for this experiment lie in matters of consciousness, knowledge, mind—“is this an ongoing operation that brain processes occasional knowledge at all or not?” (180)—Memory emphasizes the idea of remembering more than it attempts to concretize the process itself, and the book’s final collection of memories becomes increasingly citational and even appropriated. Mayer imagines herself to be Antonin Artaud, dreaming of his own wife and scenes from his own visual field (181).

The final, undated section of Memory which appears after an entry for July 31, “Dreaming,” reflects that “a month’s a good time for an experiment memory stifles dream it shuts dream up” but that given the right procedure, “dream makes memory present” (189). The book ends with the line “Now you tell me, can I say that” (195) with no ending punctuation. Mayer seems to be asking about the status of this remembered set of dreams, the entirety of Memory, as an aesthetic object: to be asking permission, but it’s not clear from whom. Like the word “remember” that breaks apart at one point, Memory textualizes memory in order to concretize its fissures and narrative gaps:

sun rising emergency parking black streaks in the sky over jeremy’s apartment sun rising emergency sun rising emergency parking bme bme bme bme bme bme bme bme bme bme bme be me be me be me be me e me be me be me bemebemebemebemebemebemebemebemebem rememrememrememrememrememrememremrememrememrememmembermember bememberrememberbememberrememberbememberrememberbemember (77-78)

The repetition in this passage on the phrase “be me” has subjective force, but both that phrase and its lexical parent (“remember”) become visually and sonically unrecognizable by the end of the passage. The end of Memory offers a plausible explanation for what has happened to the speaking subject. Here, it is as if the rewritten memory can infinitely extend consciousness, at least on the page:

Cause memory & the process of remembering of seeing what’s in sight what’s data, what comes in for a while for a month & a month’s a good time for an experiment memory stifles dream it shuts dream up. What’s in sight, it was there, it’s over, dream makes memory present, hidden memory the secret dream, it’s not allowed, forbidden, dont come out the door, there’s an assassin at it or a lion, wild Indian, a boar, a little bear upside down in the dream, so, memory creates an explosion of dream in August & I no longer rest I dont rest anymore […]. And dream’s an analogy to reprocessing in process, so rewrite it it’s changed but a memory according to how you record it now & as it could go on forever, this could, dream’s a memory kept in process kept in present by whose consciousness by whose design, so, memory creates an explosion of dream in August […] (189)

Mayer suggests a one-way relationship of memory and dream. Memory closes off the productive possibility of dream, but dream uncovers or recapitulates memory: punning on “insight” and the visuality of remembered images, Mayer insists that dream is analogous to reprocessing, but only “in process” – in procedure. This is also a rare moment of self-consciousness about the time of writing this book: this rewriting, or this Freudian “dream-thought,” takes place in August, that is, the month after the primary site of the experiment, which was the month of July. Memory uses the dream to mediate between I and the world, converting the speaking I into site.

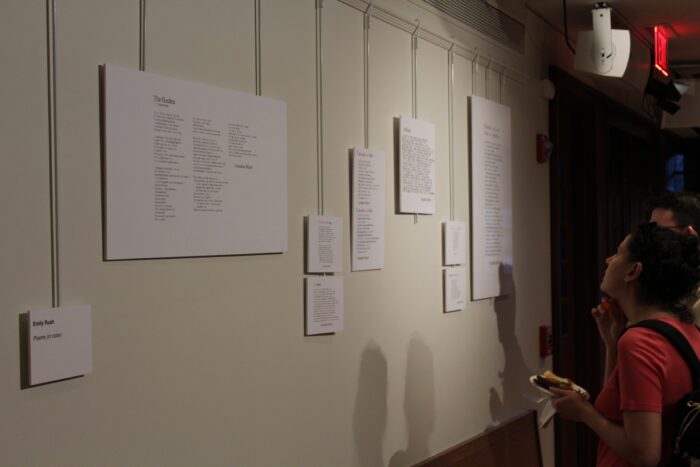

Fig. 4: Poems (in Color) by Bernadette Mayer. Opening, Brodsky Gallery, Kelly Writers House, April 2019.

Forty-eight years later, in April 2019, Mayer visited the Kelly Writers House in Philadelphia for the opening of a gallery show of large-scale prints of poems created by an undergraduate student, Emily Rush, who worked closely with Mayer to use colored letters that textualize Mayer’s cognitive experience of synaesthesia. Synaesthesia in modern and contemporary poetry has been described as a literary device, perhaps beginning with Rimbaud’s “disordering of all the senses”; it manifests in earlier periods of art and literature as a method of mixing the senses in order to experiment with perception.33 Mayer has discussed the 1994 cerebral hemorrhage that affected her ability to sustain long-form projects like Memory, but the spring 2019 installation was one of the first times she has discussed another cognitive phenomenon: her lifetime synaesthesia.34 If Memory uses the photographic image in a gallery space as mnemonic tool, the collaborative project “Poems (in Color)” juxtaposes the radical particularity of individual perception with intersubjective practice – both the creation of these works and the audience’s perception of them in the gallery space.

Fig. 5: Emily Rush and Bernadette Mayer at Kelly Writers House, April 2019. A poem from Poems (in Color).

For the purposes of the show, Mayer was described as “a synesthete who sees letters in color”: Rush created an alphabet key using Pantone colors to type a series of Mayer’s poems in color, as if to invite readers to see them how Mayer does. In their description of the project on opening night, Rush uses the terms of epistolary address and collaboration art practice:

Bernadette has synaesthesia, which means she can see each letter of the alphabet as a specific color. There was supposed to be a show in Portland, Oregon, with her poetry printed on the walls in its synaesthetic colors. That show fell through so I decided to reappropriate the idea here.

I want to talk a bit about the experience of organizing the show. Last spring, I wrote about Bernadette’s Desires of Mothers to Please Others in Letters, a collection of unsent letters written during her last pregnancy. I said, “Bernadette’s letters are bound in blue and as a reader I’m given double role. I’m not just skimming a book of poetry; instead, I’m receiving a letter. I don’t know you-know-who, I don’t know what happened on the phone call, but nonetheless I’m invited to imagine. Bernadette embraces me, lets me occupy the back end of her epistolary experiment. And I feel close to her.”

This spring, I felt similarly. Like I had permission to cross a boundary, to approach her poetry on my own terms and do with it what I wanted. Putting together the actual Poems in color was exhaustive to say the least. I used Adobe Illustrate after a YouTube crash course in the software. I copied and pasted each individual letter in alphabetical order. So yes, I’ve read each poem on the wall at least twenty-six times over.

I asked other artists and poets to contribute as well. I reached out to Kayla [Ephros], who heard Bernadette on a podcast and came over to draw a map of her dreams. I asked Alli Katz to make a comic about one of Bernadette’s classic bitchy sonnets. Laynie Browne made some collages about two days after hearing about the show. And other artists who are either here or not here to talk about their work. All of the women included did some form of the work I’d done: reading and thinking and making something colorful.

Rush’s overview of the project begins with the social forms of the poetry: converting Mayer’s cognitive experience of synaesthesia not just into visual forms but also into collaborative authorship. Rush links Poems (in Color) to Mayer’s earlier project Desires of Mothers to Please Others in Letters, which, like Moving, wrestles with how to represent temporal experience and stages an argument for a new kind of narrative. Desires shares an affinity with what Robert Glück describes as the information-saturated mode of New Narrative writing: “transgressive writing,” as he puts it in “Long Note on New Narrative,” “shocks by articulating the present, the one thing impossible to put into words, because a language does not yet exist to describe the present.”35

Rush describes themselves as a reader of Desires coming to Mayer’s Poems as co-creator, as if there were something epistolary about the collaboration to bring synaesthesia poem-making into the gallery space.

At that same gallery opening, Mayer describes synaesthesia as a private experience shaped by relational and public interpretation of it – in particular, the estranging effects of its being understood as a kind of pathology:

I noticed I had synesthesia when I was maybe five or six years old. But I didn’t tell my parents because, you know, in the world that I lived in, they would’ve just assumed that that meant that I was crazy. And, as young as I was, I seemed to know that. So I didn’t say anything about it until … probably not until I was about twenty years old.

Mayer also describes her synaesthesia as “pure pleasure”:

But it, you know, it’s a great pleasure, to have synaesthesia, so part of the pleasure is not really talking about it. I never met anybody else who had it, I didn’t travel in those circles. [Emily Rush asks: What circles?] The erudite circles, you know. [Laughs.]

And again during the opening, when asked if she’s able to “turn off” her synaesthesia while reading:

Well you have to, in order to read a book, or anything like that. But when you really are enjoying it, is when you’re writing, I think. Because it’s just pure pleasure to have—imagine your friends, the letters, right. Like, Catullus has a book, has a poem called “Come here, all my hendecasyllables,” it begins like that. And so that’s how you feel, it’s like, all my friends the letters are now in color, too? Wow. You know, that’s pretty great. [Laughs.]

And when Jason Zuzga asks, “In looking at the painting, do you have further synesthetic experiences?” Mayer again invokes the pleasurable aspects of her interpretive experience:

Oh definitely, it’s enough to make you go crazy. That’s all I’ll say about it. No but you see beautiful washing and the dancing. You know what kind of synesthesia I’ve always wanted to have? There are all different kinds, one kind is that when you speak, different rectangles or geometric things come out of your mouth.

Like Memory, Poems (in Color) exists as a gallery and print piece as well as an online archive. For both projects, the built environment of the exhibit space offers a site at which to study the self, and both are unbounded by place or by medium: Memory lives online at Eclipse; Poems (in Color) lives online in streaming video. And both projects push the implications of procedure for lyric reading: if Memory is an “emotional science project” streaming the data of dream detail in order to test the bounds of the self, Poems (in Color) takes the literal point of exchange between Mayer and one of her readers as a site for investigating empirical meaning. Rush tells the audience, “Bernadette and Phil [Good] chose the poems, and I was their scribe,” the word “their” attaching both to Bernadette and Phil, but also to the poems themselves and their co-creation in color – Rush made some curatorial choices, including assigning color to the letter “v,” altering the perception of the poems. Mayer’s experiments in language and consciousness have at times recalled Gertrude Stein’s poetic excursions into psychological inquiry, but Mayer’s procedural experiments – both the time-based Memory and the color and scale of the Writers House prints that materialize synaesthesia – also raise questions for the status of expression in lyric studies, the simultaneously self-directed and self-evacuating impulses of proceduralism, and the extent to which both approaches to poetic practice emerge from the built environment of the gallery – or from the structures of the mind.

Bernadette Mayer, “Twenty Questions about Form or New Forms,” in Onward: Contemporary Poetry and Poetics, ed. Peter Baker (New York: Peter Lang, 1996), 5-6. ↩

Myung Mi Kim, Commons (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 111. ↩

See Virginia Jackson, Dickinson’s Misery: A Theory of Lyric Reading (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2005), 129. ↩

Kim, Commons, 111. ↩

Temporal and spatial expansion as characteristics of the new modernist studies are terms described by Douglas Mao and Rebecca L. Walkowitz in “The New Modernist Studies,” PMLA 123, no. 3 (May 2008): 737-48. Despite the ways in which the argument against dehistoricized formalism is by now axiomatic for at least a good part of the field of poetry and poetics, a number of recent critical works have risen to the defense of abstract form, seeking to puzzle over whether a literary form derives from social conditions, or whether a literary form is an abstract category unfettered of history. See, for example, Caroline Levine’s Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), which rehearses a claim that “forms are not outgrowths of social conditions; they do not belong to certain times and places” (12). Levine does differentiate between “form” and “genre” and suggests that genre is the act of classifying texts in a historically specific way in the service of interpretation, whereas form is both interpretive and an abstracted principle of organization (13). Yet the claim that forms “migrate across contexts in a way genre cannot” (13) renders this distinction a fallacy, to say nothing of the allusions of a word like “migrate” and its invocation of, for example, poetic genre’s relationship to national borders. ↩

Jackson, Dickinson’s Misery, 128. As Walt Hunter has shown, the anglophone discourse of lyric studies has emerged alongside a longstanding European discourse on lyric as a matter of collective subjectivity, a discourse that pairs theories of poetry with theories of the ethical and sociopolitical self. Walt Hunter, “Lyric and Its Discontents,” Minnesota Review number 79 (2012): 81. In his book Forms of a World: Contemporary Poetry and the Making of Globalization (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019), Hunter usefully dislodges an undertheorized notion of subjectivity that characterizes much of lyric studies, arguing instead that “the terms that we use to think about poems are just as much products and producers of the liberal discursive frameworks of subjectivity, freedom, humanity, and intimacy” (5). Kamran Javadizadeh points out that lyric studies also has a tendency to reinscribe a universalizing whiteness to the lyric subject. See Kamran Javadizadeh, “The Atlantic Ocean Breaking on Our Heads: Claudia Rankine, Robert Lowell, and the Whiteness of the Lyric Subject,” PMLA 134, no. 3 (2019): 476. ↩

Peter Baker, “Bernadette Mayer,” in American Poets Since World War II, ed. Joseph Conte (Detroit: Thomson Gale, 1996), 165. ↩

Bernadette Mayer, Studying Hunger (Bolinas: Big Sky, 1975), 9. ↩

Shaw continues: “Many of the syntactical folds and complexities of the book as a whole might be thought of as enactments of these temporal blurs and overlaps – linguistic analogs, that is, for the book’s unstable tense. This tense is fractured and pluralized because the project of using photographs to help one ‘recover’ ideas or experiences from the past gets continually overcoded (and even derailed) by the subsequent lives these ideas both have taken on, and continue to take on, in the book’s present tense.” See Lytle Shaw, “Faulting Description: Clark Coolidge, Bernadette Mayer, and the Site of Scientific Authority,” in Don’t Ever Get Famous: Essays on New York Writing after the New York School, ed. Daniel Kane (Champaign: Dalkey Archive Press, 2006), 154. ↩

Mayer has said that her increased intertextuality earned her the label of “a failed experimentalist” (quoted in Baker, “Bernadette Mayer,” 168). In Midwinter Day (New York: New Directions, 1999), Mayer writes, “Barry told Clark I shouldn’t write about Lenox [Massachusetts] and he didn’t like Lenox. Someone else said I was no longer a true experimentalist” (64). ↩

Baker: “In a language made up of idiom and lyricism, which cancels the boundaries between prose and poetry, Bernadette Mayer’s aesthetic intent is moral and theological in dimension. Her search for patterns woven out of small actions confirms the notion that seeing what is is a radical human gesture. Doctrine is irrelevant” (“Bernadette Mayer,” 170). In Obdurate Brilliance: Exteriority and the Modern Long Poem (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1991), Baker includes Mayer in his study how the modern long poem can be understood as a form of ethical practice characterized by “exteriority,” which Baker defines as “the ethical thrust of linguistically aware intersubjectivity” (150), or the outward movement of poetry that deliberately engages with the experience of others in general and with the reader in particular. Linda Russo likewise suggests that Mayer’s work follows the logic of the procedural text rather than the logic of the subjective ‘I’ (“Poetics of Adjacency: 0-9 and the Conceptual Writing of Bernadette Mayer and Hannah Weiner,” in Kane, Don’t Ever Get Famous: Essays on New York Writing after the New York School, 140). Joseph Conte describes the postmodernist preoccupation with procedural form as antilyric: “Procedural form presents itself as an alternative to the well-made, metaphorical lyric” (Unending Design: The Forms of Postmodern Poetry (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991), 3. ↩

Bernadette Mayer to Alice Notley, 27 January 1980, published as part of Alice Notley’s lecture “Doctor Williams’ Heiresses” (San Francisco: Tuumba, 1980), n.p. Ellipses Mayer’s. ↩

Mayer writes in Studying Hunger: “MEMORY was described by A. D. Coleman as an ‘enormous accumulation of data.’ I had described it as an ‘emotional science project.’ I was right” (9). ↩

Freud explores the work of “condensation” in the forgotten or fragmentary dream, differentiating between “dream-content,” or dream narrative, and “dream-thoughts,” or the way associative material of the dream manifests in waking life. See Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, trans. James Strachey (New York: Basic Books, 1955), 212-13. ↩

Leslie Scalapino, interview with Sarah Rosenthal, Jacket 23 (2003). ↩

Bernadette Mayer, “Experiments,” in The L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Book, ed. Bruce Andrews and Charles Bernstein (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1984), 80. ↩

As Nelson points out, “Mayer’s experiments with collaborative, performative writing – often enacted in her workshops, and then recorded in the anonymously authored magazine Unnatural Acts – explicitly set out to disregard the sanctity of the monolithic author or text,” a goal Nelson aligns with the history of performance art. Nelson sees the “Experiments” as another instance of this method. See Women, the New York School, and Other True Abstractions (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2007), 103. ↩

Mayer, “Experiments,” 83. ↩

In a personal interview with me in 2006, Mayer definitively resists affiliation with Language writing, not least by pointing out her role as an instructor: “Well, I never was a part of the Language School. I mean, I taught those guys what they needed to know, but it was only because they asked me to. But Clark Coolidge and I used to figure like that we were the founding members of the Language School, but if you want to go back further, you would go to John Cage. Right? I mean, so, really, what difference does it make?” Mayer’s resistance has been further documented by Nelson, Russo, and others. Still, Jerome McGann sees “Experiments” as speaking to “a number of the most important characteristics” of the Language School, including its insistence upon writing as praxis: “In the first place, writing is conceived as something that must be done rather than as something that is to be interpreted. […] Meaning occurs as part of the process of writing – indeed, it is the writing.” See “Contemporary Poetry, Alternate Routes,” Critical Inquiry 13, no. 3 (1987): 636. ↩

Shaw, “Faulting Description,” 154. ↩

Shaw, “Faulting Description,” 154. ↩

Shaw, “Faulting Description,” 156. ↩

Mayer and Dale Worsley, The Art of Science Writing (New York: Teachers and Writers Collaborative, 1989), xiv. ↩

Mayer and Worsley, The Art of Science Writing, 44. ↩

Mayer, “Experimental Writing, or Writing the Long Work Poems,” in Baker, Onward, 6. ↩

Mayer, “Experimental Writing,” 8. ↩

Mayer, “The Live Poet’s Society: Where Feminism and Poetry Intersect,” interview with Daniel Kane and Lisa Jarnot, Ms. Magazine 11, no. 4 (2001): 86-87. ↩

Mayer, Memory (Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 1975), 189, 188. Hereafter cited in text. ↩

Russo, “Poetics of Adjacency,” 148. ↩

Russo, “Poetics of Adjacency,” 128-29. ↩

Russo, “Poetics of Adjacency,” 134. ↩

Libbie Rifkin has also written on Mayer’s and Anne Waldman’s roles in the gendered institution-formation of St. Mark’s Place during this period; see “‘My Little World Goes On St. Mark’s Place’: Anne Waldman, Bernadette Mayer and the Gender of an Avant-Garde Institution,” Jacket 7 (April 1999). Kane has written on Mayer’s, Waldman’s, and Warsh’s production of a “localized poetics of sociability” that contrasted with “the disengaged tenor of first-generation New York school” practices: see “Angel Hair Magazine, the Second-Generation New York School, and the Poetics of Sociability,” in In Kane, Don’t Ever Get Famous, 349. ↩

Arthur Rimbaud, Illuminations (New York: New Directions, 1946), xxvii. ↩

In an interview with Lisa Jarnot, Mayer remarks that the hemorrhage also afforded her new opportunities to investigate the workings of the mind: “I’ve always been interested in the brain and consciousness. I mean it’s amazing that I had a cerebral hemorrhage and now I see all these neurologists and am concerned with all these things in a different way. I think it’s great actually. I shouldn’t say that. I learned in the hospital that you’re not supposed to think a cerebral hemorrhage is interesting in any way. Otherwise you get accused of having a sense of unreality. One nurse actually said to me, ‘You don’t realize what happened to you’” (quoted in Nelson, Women, the New York School, and Other True Abstractions, 102). In a personal interview with me in 2006, Mayer remarks that the hemorrhage has also affected her ability to sustain long-form projects into her current writing practices: “I wrote a lot of epigrams, and I finally got somewhere with them. So now it’s a form that I can do. It’s also good for my current way of being because I had a stroke in 1994 and it’s easier to remember, I have to rely on my memory a lot, and it’s easier to remember short poems than long ones, that’s for sure.” ↩

Robert Glück, “Long Note on New Narrative,” Biting the Error: Writers Explore Narrative (Toronto: Coach House, 2005), 31. ↩

Article: Creative Commons NonCommerical 4.0 International License.