Naomi Elena Ramirez, Choreography for Smartphone Gestures (2016), on Vimeo.

Ideas are products of their environments. It’s no accident that when a new paradigm of media studies appeared on the scene going by the name of “media archaeology,” scholars were in the process of turning on their first smartphones and gawking at their friends’ new tablets.1 Media archaeology foregrounded the paths not taken, the dead ends and minor figures of media history – files and the phonautograph, optical toys and the Dynabook.2 These artifacts were historical lenses through which, if only indirectly, our inscrutable new gadgets could be seen in terms of what came before.

A decade later, digital devices are an embedded part of daily life. Far clearer are the changes they have introduced to politics, relationships, and our sense of the world around us. Smartphones are no longer curiosities or unknown quantities, they form privileged relationships with their users that can be characterized by sensuousness, intimacy, virtuosity, even fetishism. Perhaps for this reason, scholars are increasingly adopting approaches to the use of media technology, from philosophies of technique, habit, and know-how, to histories of neglected ideas like psychotechnics, the useful arts, and the chaîne opératoire.3

This issue of Amodern profiles some of the many ways that scholars of media, technology, and culture are extending the object-orientation of media archaeology. What are the methods, terms, and concepts that have been useful in shifting our emphasis from tools to their applications? How do we describe the use of media and at what point do these descriptions take on an interpretive dimension? As Jocelyn Holland shows in her contribution on “the semantic and discursive histories of Technologie” in eighteenth-century Germany, technical objects are no more complex than the terminologies describing their use. This includes “the methods of production unique to various arts, but also those words which refer to materials used by artisans, different kinds of crafts, and the wares produced by them.” Words and genres of description proliferate alongside the developing complexity of the phenomena they describe.

The title of the issue you are now reading is borrowed from an essay Marcel Mauss contributed to a 1941 conference on techniques in Toulouse, France. During a time when the most basic aspects of traveling, writing, and thinking were made near impossible, a group of scholars committed to the study of history as an embodied, lived experience gathered to discuss “techniques and technology,” as well as the terminology available for conceptualizing the relationship between the two. Ignace Meyerson, a psychologist interested in history, invited historians interested in psychology. Most of the presenters were associated in one way or another with Annales d’histoire sociale, the influential journal founded in 1929 by Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre, who also attended.

For years, the Annales circle had been discussing the need for a new approach, method, or discipline devoted to technique. Mauss wrote in 1927 that “we have never had the time and strength necessary to give technical phenomena the formidable place they deserve.”4 Bloch argued in 1932 that “nothing would matter more to the progress of our historical research than good work on the evolution of various techniques.”5 Lucien Febvre introduced a 1935 issue of Annales devoted to the subject.6 And Ignace Meyerson opened the Toulouse gathering in 1941 by arguing that older fields devoted to the applied study of technique (physiology, scientific management, psychotechnics) needed to be replaced by new historical approaches capable of exploring technique “from its first artisanal and rural forms to contemporary machinery.”7 The conference was the culmination of these long-running discussions.

Technique is a French word that is far more capacious than its English cognate. When Mauss writes technique, he might refer—as one would in English—to skills, methods, and procedures: the way we do things. But he also uses technique to refer to the tools that augment those actions. The “bear claw” we learn in the kitchen to guide a precise knife cut, fingertips curled under with knuckles against the edge of the blade: both gesture and tool here are technique. English translators render the term as technique or technology depending on the context. In translating Marc Bloch’s discussion of the two different shapes that farm plots could take in medieval France, for instance, Janet Sondheimer has the benefit of variety with English-language terminology. One Bloch’s technique . . .

. . . the prime reason for the contrast between two types appears to lie in an opposition between two techniques [l’antithèse de deux techniques]

. . . is another Bloch’s technology:

. . . the wheeled plough must undoubtedly be regarded as a creation of the agrarian technology [une création de cette civilisation technique] which ruled the northern plains.8

In English, we haven’t really had the benefit of a single word that encompasses both techniques and technologies: the way we do things and the tools we use to do them. Lacking that word has perhaps led to some of the constitutive differences between English-language media theories and those produced by French, German, and Spanish-speaking scholars.9 (Lewis Mumford and Thorstein Veblen’s technics never achieved widespread use, save for the hi-fi turntables.)10 What if Anglophone media scholars tend to be divided into fields that focus either on technologies (platform studies, media archaeology) or techniques (film theory, communications), simply because our terminology addresses techniques and technologies separately? Mingyi Yu’s remarkable study in this issue, on the development of computer science in the 1970s and 80s—a story of “the changing epistemological significance of procedures”—illustrates one consequence of this divide: media theorists tend to view code primarily as functional circuitry rather than as a matter of habits, techniques, and forms of thought, as did key figures in the development of a discipline called “computer science.”

In Toulouse, the study of technique led conference participants to speak on topics ranging from the ethnography of labor to changing ideas of “work” throughout history, from scientific practices, to monastic rituals, and the routines of seventeenth-century peasant life.11 Diverse as their subjects were, presenters agreed that the word technique lacked the precision necessary to describe ongoing developments in modern machinery, weapons, and media. This desire for greater clarity in the study of modern humans and their advanced tools would be accelerated by the end of the war, as new monstrosities emerged from its ashes. How could the same term encompass both abacus and computer, throwing spear and atomic bomb?12

In their writings on technique in the years prior to the Toulouse conference, Mauss and Bloch both struggled to define the concept. They stretched it beyond its common sense, at times trying to make the word do things it was never meant to do. For Bloch, new techniques emerged throughout history due to a mixture of political, cultural, and social determinants. In his view, the precise chain of causality between those elements was impossible for historians to discern given the limitations of their methods at the time. As a sociologist, Mauss tried to differentiate the functional use of tools from the imaginary use of tools in magical or religious rituals.13 Mauss’s famous 1935 essay on “body techniques” suggests that the body is the first tool we ever use: “I made, and went on making for several years, the fundamental mistake of thinking that there is technique only when there is an instrument.” What would it mean instead to see the body as our “first and foremost natural instrument?”14 Walking, swimming, yawning, pointing: each of these practices involve forms of imitation, creativity, and skill.15 Mara Mills writes of voice techniques—“voice affords an excess of sound-making beyond speech”—in ways that resonate with this approach. Her contribution to this issue recovers the qualities of early-twentieth-century “queer voice” by reading against the grain fragments of “novels and phonetics textbooks, with acoustic or anatomical clues by which we might reanimate them.”

Today, technique continues to be a site of dialogue and improvisation. Techniques can be thought of as mundane and habitual (tying your shoes), but they can also draw on forms of unstandardized expertise or tacit knowledge (getting a screw to catch using the old carpenter’s trick of sliding a toothpick into a stripped hole). Several contributors to this issue explore the relationship between these different understandings of technique, asking what lies between the habitual and the tactical. James J. Brown, Jr., for example, argues that “our current communication infrastructure is part of a long history of medium labor being pushed on to marginalized people,” from early-twentieth-century telephone operators who were “taught to diffuse situations, to absorb and redirect energy,” to the women, people of color, and those in the LGBTQ community today who have developed strategies of amplification and reframing to combat abuse and harassment on social media. Their “techniques [have] been honed over centuries of rhetorical practice.”

Each of these techniques are of course far more than a simple means of getting something done. Liam Cole Young, in his contribution on Harold Innis’s research practices, argues that “techniques of doing generate concepts and even objects of inquiry rather than the other way around.” Techniques are interpretations of the world around us, arguments about the ways that things can and should be arranged. Somewhere between the deep grooves of repeated habit and the exceptional performance of virtuosity, contributors to this issue of Amodern view techniques as concepts: built to serve a need in a particular moment, subject to cultural and historical context, constantly in flux and dialogue.

❀ ❀ ❀

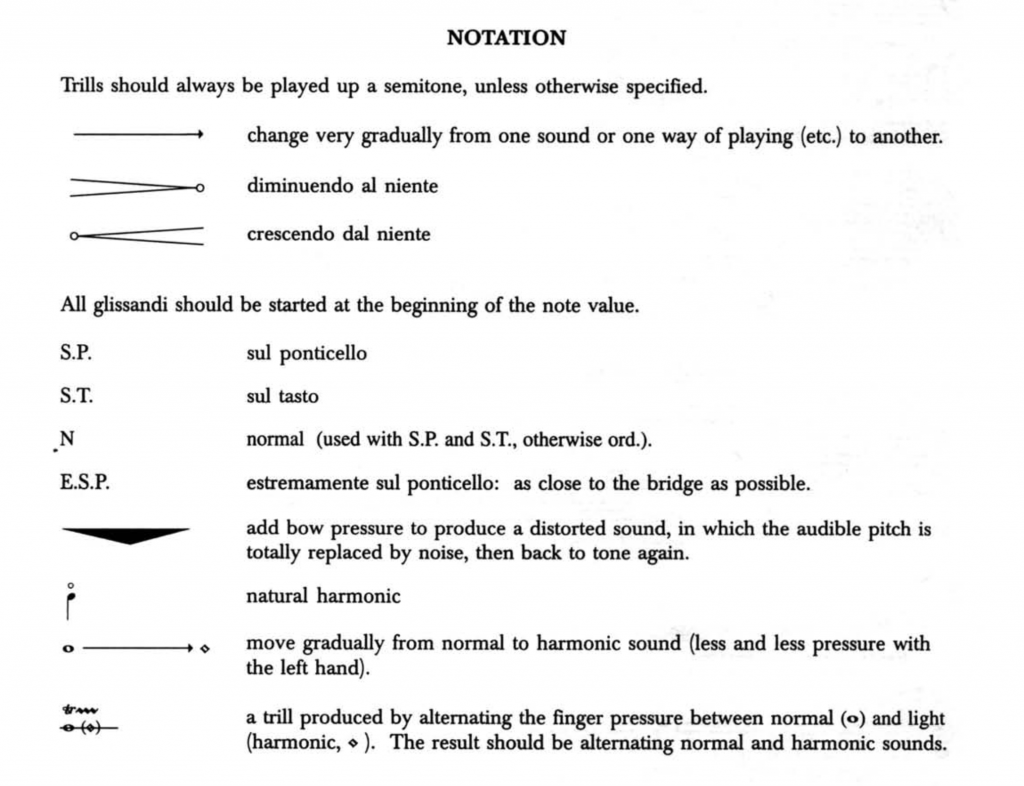

The perfect soundtrack to these essays can be found in new music, where composers increasingly take up technique as a means of generating musical ideas. Twentieth century composers experimented widely with tonality, pitch, dynamics, and rhythm, even writing music that cut across such distinctions. Victoria Simon examines a graphic tablet interface invented in 1977 by architect and composer Iannis Xenakis that allowed users to approximate the sound of any instrument by drawing waveforms. But contemporary composers have further expanded this sonic palate with scores that contain explicit instructions for musicians to play traditional instruments in unusual ways. This new channel of expression, known as “extended technique,” essentially allows the composer to experiment with a fuller range of sounds than an instrument can possibly make. Andrew Norman—whose symphony Play is structured like a video game—releases a series of instructional videos for each of his works that provide detailed descriptions of new techniques like the “dirty gliss.”

Kaija Saariaho is particularly well-known for incorporating techniques that produce percussive or noisy sounds into more traditional harmonies. In a performance of Sept Papillons [Seven Butterflies], the cellist Danielle Cho incorporates two extended techniques simultaneously: first, fingered harmonics, in which the performer is instructed to alternate the pressure of her fingers against the strings. Cho’s left hand presses the string down completely against the fingerboard and then gradually reduces pressure until her fingertip is just lightly touching the string. This light pressure creates a harmonic overtone, where the normally played note sounds out several octaves higher.

Doubling this effect is the movement of her bow hand up and down the strings. Normally, the bow plays roughly between the end of the fingerboard and the bridge. But Saariaho’s score directs a gradual movement of the bow from sul tasto (near the finger board) to sul pont (at or even over the bridge.) Normally, moving the bow is exactly the opposite of what a musician wants to do when trying to create fingered harmonics because it ends up producing a nasal or even glassy tone. But that’s exactly the rough, glassy, effect that Saariaho is after here. She elevates technique to the level of more familiar musical elements like harmony and rhythm, integrating these new sounds into traditional structures in a way that “applies familiar concepts in an unfamiliar fashion.”16

Kaija Saariaho: Sept Papillons | Danielle Cho, cello from H. Paul Moon on Vimeo.

Musicians speak of speak of timbre to describe these sounds, but they also use words evoking sight and touch: color, shaping, and texture, even meaning. Anssi Karttunen, the cellist for whom Saariaho wrote Sept Papillons, describes these sounds as a “piece of music that’s not music, it’s material falling apart. . . . With a lightness of touch, it always has this feeling that you have more fingers than you think. . . . The thing that we as interpreters have to learn is how to assimilate [extended techniques] so that they sound like part of a language.”17 These extended techniques do more than just produce interesting sounds, they also expand the repertoire of what’s considered “traditional” in Western music. The sitar, for instance, a North Indian classical instrument with sympathetic strings that constantly resonate in overtones as the musician plays, produces sounds similar to the “flutter” technique in several Norman pieces.18

If a single instrument affords an entire universe of sound, we might transpose these questions into scholarship on media, technology, and culture by asking: how can we write about the diversity and range of techniques in ways that exceeds what can be interpreted from the shape of a single technical artifact? How should a consideration of the techniques of the individual user be connected to a broader sense of the interconnection of these users and their techniques? Shannon Mattern for example, in her essay on techniques of privacy, secrecy, and security, describes a kind of dialogue between eighteenth-century makers of “furniture that supported reading and writing and storing and secret-keeping, [and] those furnishings’ owners [who] had to develop new techniques, too—not only for literacy and organization but also for operating the furniture itself.”

How can individual techniques be connected to a broader accounting of their cumulative effects? And then what happens when individual techniques are instead systematized, interwoven, or locked into a particular frame of reference? For Jeffrey Moro, this means the logic of the geographic grid and “the media techniques that meteorologists use to wrangle . . . data and translate them into useful forecasts.” For Matthew Hockenberry, this means the supply chain, a term first proposed in the early 1980s for “managing the previously separate systems of production, marketing, distribution, sales, and finance as though they were a single entity.” (Hockenberry draws on a student of Mauss’s, André Leroi-Gourhan, and his concept of chaîne opératoire.) And for Casey Boyle and Nathaniel Rivers, this means ambience as “a concept that helps us understand communication as more than one person speaking to another through some medium,” in their essay on captioning. Boyle and Rivers bridge scholarship on disability and the German media theory of Kulturtechnik [cultural technique]—most prominently developed by Bernhard Siegert—an important touchstone for several scholars in this issue.

Rounding out all of these approaches to technique, this issue of Amodern includes the first English translations of the Historisches Wörterbuch des Mediengebrauchs [Historical Dictionary of Media Usage], an ongoing project soon to publish its third volume. The Dictionary contains over a hundred entries like posting, browsing, serializing, typing, and imitating. Authors define each term through stories of media usage in specific contexts, favoring individual acts over forms of media: not cinema, but filming. Not social media, but liking. As Hannes Mandel writes in his introduction to the section of translations, “Strategically undermining . . . conventional periodization, the Dictionary offers a whole array of new historical vistas that inform our present as much as they provide new insights into the past.”

❀ ❀ ❀

In 1941, one of the questions raised during the Toulouse conference was: how could scholars in the humanities and social sciences approach objective, mechanical facts of efficiency and instrumentality in ways that engineers and technicians couldn’t? How could the study of historical techniques inform the planning and design of new technologies? In his essay (delivered in absentia), Mauss used the term technologie [technology] to suggest one answer to this question.19 Before technology meant “machines” or “electronics” (as it does in English today), the term signified a way of studying and thinking about tools. In the same way that psychology is the study of the psyche and musicology the study of music, technology for Mauss was to be a new field of study devoted to the history, culture, and psychology of techniques. If technique is the way we do things, then technology asks what it means that things are done a certain way.

Today, technology is the object studied rather than the field of study. But it seems that the terms in which we understand that object have begun to shift. In 1941, Mauss saw “. . . machines used to produce in series even more precise and immense or compact machines, which themselves serve to manufacture others, in a never-ending chain in which each link is built. . . . Even the most elementary technique, such as that relating to food production . . . is becoming integrated in these great cogwheels of industrial plans.” His speculative notes toward “planning” at this essay’s close suggested a technologie in which scholars and policymakers might better coordinate the ensemble of individuals, machines, and societies that were now inextricably linked. “Techniques intermingle, with the economic base, the workforce, those parts of nature which societies have appropriated, the rights of each and or everyone—all crosscut each other.”20

One of the things suggested by the essays in this issue is that academic fields continue to change in concert with their objects of inquiry. Whether we are studying eighteenth-century makers of hats in Germany and furniture in France, or 1920s processors of weather data in Britain and telephone calls in the US, the way we understand the past is irrevocably bound up with and enriched by our present-day analogues. And so today, it is becoming increasingly difficult to speak in vague terms like materiality when scholars are developing new ways to describe how a single touchscreen swipe depends on an ever-growing assemblage of rare-earth materials and labor exploitation.21 Or reductive phrases like new media when the application of machine learning to everything from healthcare and housing to streaming and advertising disproportionately impacts marginalized communities. These essays gesture toward an approach to media, technology, and culture that uses technique, in all of its variety, as a means of mapping such constantly evolving relations between users and devices, users and users, devices and devices.

One primary aim of media archaeology was “writing counter-histories to the mainstream media history, and looking for an alternative way to understand how we came to the media cultural situation of our current digital world.” Jussi Parikka, What Is Media Archaeology?, (Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2012), 6. See Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka, “Introduction: An Archaeology of Media Archaeology,” in Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 1–21 for an intellectual history of the phrase “media archaeology.” ↩

See Cornelia Vismann, Files: Law and Media Technology, transl. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, (Stanford University Press, 2008). Paul DeMarinis, “Erased Dots and Rotten Dashes, or How to Wire Your Head for a Preservation,” in Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications, ed. Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka, (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 2011), 211–238. Thomas Elsaesser, “Early Film History and Multi-Media: An Archaeology of Possible Futures?” in New Media, Old Media, ed. Wendy Hui Kyong Chun and Thomas Keenan, (Routledge, 2006), 13–24. Casey Alt, “Objects of Our Affection: How Object Orientation Made Computers a Medium,” in Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications, ed. Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 278–301. ↩

For writings on technique, habit, know-how, psychotechnics, the useful arts, and the chaîne opératoire, respectively, see: Ernst Kapp and Siegfried Zielinski, Elements of a Philosophy of Technology: On the Evolutionary History of Culture, ed. Jeffrey West Kirkwood and Leif Weatherby, trans. Lauren K. Wolfe, (Minneapolis ; London: Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2018). Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016). Jason Stanley, Know How, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013). Jeremy Blatter, “Screening the Psychological Laboratory: Hugo Münsterberg, Psychotechnics, and the Cinema, 1892-1916,” Science in Context, 28, no. 1, (March 2015): 53–76, doi:10.1017/S0269889714000325. Eric Schatzberg, Technology: Critical History of a Concept, (Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press, 2018). Nathan Schlanger, ed., André Leroi-Gourhan on Technology, Evolution, and Social Life: A Selection of Texts and Writings from the 1930s to the 1970s, (Bard Graduate Center, 2020). ↩

Mauss grants the exception of his friend and collaborator, the archaeologist Henri Hubert, who was “by profession a technologist.” Marcel Mauss, Techniques, Technology and Civilization, ed. Nathan Schlanger, (New York: Durkheim Press, 2014), 50. Originally published as “Divisions et Proportions des Divisions de la Sociologie,” Année Sociologique, 1927. ↩

Marc Bloch, “Problèmes d’histoire des techniques,” Annales, 4, no. 17, (1932): 482–486. ↩

Lucien Febvre, “Réflexions sur l’histoire des techniques,” Annales, 4, no. 36, (1935): 531–535. ↩

“Humans at work are better understood through the history of work and techniques: a material history that is at the same time a social, moral, and psychological history.” [L’homme au travail se comprend mieux par l’histoire du travail et des techniques: histoire matérielle et en même temps histoire sociale, morale et psychologique.] Ignace Meyerson, “Le Travail: Une Conduite,” Journal de Psychologie Normale et Pathologique, 41, (March 1948): 7–16. For the reception of these ideas among French historians like Maurice Daumas and Bertrand Gille, see François Jarrige and Raphaël Morera, “Technique et imaginaire,” Hypothèses, 9, no. 1, (2006): 163–174, doi:10.3917/hyp.051.0163. ↩

Marc Bloch, French Rural History: An Essay on Its Basic Characteristics, trans. Janet Sondheimer, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966), 50, 52. ↩

“. . . almost all Continental languages have a cognate of technique that can be translated into English as ‘technology.’ For example, ‘history of technology’ in French is l’histoire des techniques, in German Technikgeschichte, in Dutch techniekgeschiedenis, in Italian story della tecnica, and in Polish history techniki.” Schatzberg, Technology, 8. ↩

Schatzberg, Technology, 147-151. ↩

Fernand Braudel, acknowledged as leader of the Annales school’s second generation, published notes on the conference a decade later. Fernand Braudel, “Note dans le Journal de Psychologie (1948),” Annales, 6, no. 2, (1951): 242–242. The proceedings themselves were published as Ignace Meyerson et al., Le Travail et les Techniques, special issue of Journal de Psychologie 41 (1948). ↩

For more on the history of “la technique” in French, see Jean-Jacques Salomon, “What Is Technology? The Issue of Its Origins and Definitions,” History and Technology, 1, no. 2, (January 1984): 113–156, doi:10.1080/07341518408581618. ↩

Marcel Mauss, A General Theory of Magic, (London; New York: Routledge, 2001). ↩

Mauss, Techniques, Technology and Civilization, 82. In another context, Mauss paraphrases Maurice Halbwachs, a sociologist associated with Annales, who argued that “man is an animal who thinks with his fingers.” “Conceptions Which Have Preceded the Notion of Matter” (1939), in ibid. ↩

Originally published as Marcel Mauss, “Techniques Du Corps,” Journal de Psychologie, 32, (1935): 271–93. The essay was an address to the Société de Psychologie Française on May 17, 1934. ↩

Vesa Kankaanpää, “Dichotomies, Relationships: Timbre and Harmony in Revolution,” in Kaija Saariaho: Visions, Narratives, Dialogues, ed. Jon Hargreaves, (Routledge, 2011), 159–176. ↩

“Extended Techniques for Strings: Kaija Saariaho and Anssi Karttunen Workshop,” Carnegie Hall, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T32QIOAxrlo, accessed December 5, 2019. ↩

In an interview, Kaija Saariaho says that the “violin has such a rich history in many cultures, and those techniques we call ‘extended’ . . . are of course completely natural. It’s just strange that in our Occidental, classic music education, we have somehow diminished this area.” Jennifer Koh, “Finnish Icon Kaija Saariaho,” New Sounds, (https://www.newsounds.org/story/finnish-trailblazer-kaija-saariaho/, June 2017). ↩

Mauss, Techniques, Technology and Civilization, 149. ↩

Mauss, Techniques, Technology and Civilization, 151-2. ↩

See Tim Ingold, “Materials Against Materiality,” Archaeological Dialogues, 14, no. 1, (June 2007): 1–16. Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski, eds., Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015). Jack Linchuan Qiu, Goodbye iSlave: A Manifesto for Digital Abolition, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2016). Nick Dyer-Witheford, Cyber-Proletariat: Global Labour in the Digital Vortex, (London: Pluto Press, 2015). ↩

Thanks to Eric Schmaltz, who illustrated this issue with stills from Intereactions (2017, with Graeme Ring and Kevin McPhee, in the Soil Arts Festival, St. Catharines).

Article: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Image: "Intereactions," (Screenshots) by Eric Schmaltz with Kevin McPhee and Graeme Ring (2017).