With a small shift in verb tense, article and capitalization, this special issue asks, answers by asking, then asks again, two question of its title. First, what is a poetry series? Second, what was The Poetry Series?

Let’s take the second one first, and the first, broader question will be answered in the process. Starting in 1966, and for approximately eight years (we’re still learning about these events), an annual poetry reading series called “The Poetry Series,” organized by English Department professors Howard Fink and Stanton Hoffman, among others, was held on the campus of Sir George Williams University (SGWU) – now Concordia University – in downtown Montreal.

For four years starting in 2010, a team of literary scholars, designers and librarians at Concordia has been working with tape recordings and other materials that document The Poetry Series to create a digital spoken word archive for literary research. That project, and that digital archive, is called SpokenWeb. Some preliminary research has already been published that both frames the case study materials that comprise The Poetry Series fonds and outlines the aims and findings of the digital presentation of these analogue audio materials via SpokenWeb. For example, Jason Camlot’s, “The Sound of Canadian Modernisms: The Sir George Williams University Poetry Series, 1966-1974” (2012), provides an overview of The Poetry Series in the context of efforts in the 1960s and 70s to define a Canadian national literature in relation to American poetics, and reads it as a platform for the performance of contending modernist and avant-garde definitions of poetry and methods of poetic practice. And a duo of articles published by Annie Murray and Jared Wiercinski in First Monday (2012) and Digital Humanities Quarterly (2014) present a methodology for designing web-based sound archives intended for critical engagement with literary recordings, and propose tools, features and functionalities that facilitate and enable such critical engagement.

This issue and its individual contributions are extensions of these foundational investigations as they use The Poetry Series as a touchstone for different modes and avenues of critical literary, media and historical analysis.

Discovery, Transformation and Transcription

The Poetry Series issues a chain of scholarly exploration that has been dependent on accidents and interventions. The story of The Poetry Series begins with Jason Camlot’s “discovery” of the tapes by chance back around 2000. Camlot noticed several long colorful rows of reel-to-reel tape boxes stored out of use’s way in a senior colleague’s office. When Camlot asked about the boxes, his colleague replied that they were “tapes of some reading series that happened a long time ago.” As revealed in Christine Mitchell’s interview with Mark Schofield, former head of technical services at SGWU who oversaw recording operations of The Poetry Series, it was a regular fear of the operators and technicians who carried out the production and preservation of these and other documentary recordings at SGWU “that materials like that would just end up in somebody’s office.”1 Audio-visual materials ending up “in somebody’s office” signified artifacts no longer in use, out of general circulation, and unlikely to be meaningfully preserved over the longer term. With The Poetry Series tapes, the operators’ worst fears had been realized.

Or, they might have been, had this particular hidden collection found its way into the departmental destroy box or the dumpster, as other sets of documentary materials from the period no doubt already have, or are poised to do, from such provisional and derelict resting places as shoe boxes and fading garbage bags on garage and furnace room floors, and on top shelves of basement cedar closets across North America. Instead, this chance question prompted the senior colleague to deposit the tapes in the ongoing Department of English fonds in the Concordia University Archives. And in the Concordia University Archives they sat, as perfectly useless a collection as before, with the one distinction that they were now catalogued, registered artifacts in the institutional system. A collection, hidden in full view, became differently hidden.

The story of The Poetry Series tapes as artifacts for digital presentation thus begins as the story of a hidden collection, for which there are two possible narrative trajectories: stories of discovery or stories of loss. The story of The Poetry Series became one of discovery.2 Following their initial deposit and basic cataloguing, the next significant phase of the tapes’ discernibility was achieved when the University Archives received a grant in 2010 to have them digitized and stored as WAV files on archival quality compact discs. At about the same time, Camlot remembered that the tapes existed and decided to find out what had happened to them. Directed by his colleague, the depositor, to the English fonds, Camlot saw the CDs and started working towards the expanded discoverability of the collection.

As a collection of digitized files on CDs, The Poetry Series audio was only slightly less useless for research than it had been when stored on reels of magnetic tape. There were no tape indexes, and no contents lists. The only way to find out what was on the tapes was to listen to them, and the next step entailed doing just that. With assistance from university archivists, Camlot and two graduate students transferred the files to a hard drive and then, using Transcrivia transcription software, they time-stamped the segments of each reading in the series, transcribed all extra-poetic speech, and marked the start and end times of each individual poem read. The beginnings of a catalogue to the collection (in hard copy and pdf) were built around these first time-stamps and text transcriptions. Thus, discoverability and navigation for the 100+ hours of Poetry Series audio was first approached as a text-based solution, and this tool allowed scholars to find out what was on the tapes (or CDs) without doing any listening at all. The tool provided a comforting, useful and quickly analyzable (if thoroughly distorted) image of the documentary sound recordings, whose tape-bound temporality is, in many ways, far less useful for critical manipulation and thinking than writing has proven to be, a point made at length by Walter J. Ong.3 Transcriptions are easily searched, compared, excerpted, and enfolded into subsequent writing and research. Used extensively in the practice of oral history and, in part due to work done in that discipline, transcription has come to be understood and theorized as a thick interpretive act in its own right.4

The Poetry Series transcriptions were therefore not simply a means to a navigational end, but were themselves initial experiments in a longer-term consideration of what transcription as an interpretive act can be. How does one go about transcribing a poem that is heard in a tape recording? What transcription rules, protocols, or rationale should be adopted? Do you punctuate? Do you lineate? Do you develop a unique form of typographical or inscriptive presentation? Perhaps one that is page-centered, barren of punctuation and all lower case, that exaggerates the spaces between words or units of utterance, along the lines of David Antin’s own approach to rendering print versions (printed poems) derived from the tape documentation of his live talk poems. Or do you make transcriptions schematic, graphical, gestural and aesthetically pleasing, like the pictoric scores of sound poet Jaap Blonk?5 What is the status of any particular transcription in relation to the published, printed version of that same poem? Printed transcriptions of spoken events, of speech acts, demand a certain degree of envoicement from the reader, and a significant pleasure comes with the reconstruction (or imagination) of voice through reading a text that is presented as a transcript of someone speaking. One need only read collections such as Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain’s Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk, or Victoria Stanton and Vince Tinguely’s Impure: Reinventing the Word — The Theory, Practice and Oral History of Spoken Word in Montreal, to understand the satisfaction that comes with tracing a stream of individually transcribed voices from the beginning to the end of a printed book.6 The playful “Transcript Collage” that forms part of this special issue, comprised of transcription excerpts from audio recorded voices of poets who read in The Poetry Series, as well as individuals interviewed about The Poetry Series and poetry reading over the last few years, engages the reader in just that kind of pleasure, even as it exploits the devious agency of transcription to excise and excerpt, misquote, juxtapose out of turn, and thus redefine the context of any historically situated utterance. As a concentrated sketch of the Poetry Series, its journey from recording to transcription and to ensemble remixing and decipherment stands in for the chain of confrontations afforded by poetry series in general.

Transcripts were thus not ends in themselves for the SpokenWeb project, but represented avenues and enactments of navigational writing, descriptive détournement and critical engagement with sound-recorded speech, a means of meditating upon the implications of the typographical representation of a sound recorded poetry series. Transcription, functioning as a first and very obvious method of remediation, signaled the great complexity (and exciting differential plenty) that subsequent acts of contextualizing The Poetry Series tapes would entail. Insofar as poetry reading series, and the archive that survives in their wake, are significantly hybrid entities, the SpokenWeb project has been determined to approach The Poetry Series (and “the poetry series”) as a sequence of experiments in the construction of historiographical formats.

When it came to embarking upon the digital presentation of The Poetry Series, that same time-stamped transcription text became data for use in digital design. Text and timestamps, integrated into a Content Management System (CMS), became one way of structuring a listener’s navigation of the large corpus of audio that comprises The Poetry Series collection. By “tethering” our digitized audio to the transcribed data, we began to explore “multimodal (i.e., auditory and visual) interactions with an interface” of literary sounds.7 In designing such an interface, the literary historian necessarily embarks upon a project of practical decisions and impasses, each of which highlights the opportunities and limitations of new media in rendering structural coherency to a series of public, historical and literary occasions.

Historiography, Criticism and the Digital Condition

The poetry series (small case, now) as an object of inquiry has, in fact, come increasingly to light as digital media offer new opportunities to recover, archive and interact with sound recordings of historical literary events. As historical and material objects, however, poetry series are unwieldy. They begin with material traces of events about which we may know very little, and then, through our interventions, beg to expand in multiple directions. In our immediate case, what starts out as a box of tapes and ends up as a list of digital files purports to be an archive of an event. But this unity might go by several other names, depending on one’s perspective or momentary priority. A digital sound archive of a poetry event. An acoustic archive of a performance event. An oral history archive of a sociocultural event. A media archive of a campus event. A stylistic archive of a linguistic event. An archive of audible poetics. A research project website.

These layerings, in turn, take the poetry series in new directions, inviting new reflections, new orderings and accumulations of new materials. These layerings are perhaps best understood as episodes in critical and creative framing. How many ways can one approach a poetry series from the micro to the macro? How many framings can we, as literary and cultural critics and historians, communications theorists, electroacoustic musicians, poets, computer scientists, linguists, digital designers, librarians and archivists, performance artists, digital humanists, etc., etc., come up with? The list we could generate, collaboratively, is expansive. With SpokenWeb, we have focused, in particular, on methods of historical situating, both in the form of documentary research, and through the pursuit of the development of an oral history archive that provides context for the events based upon the accounts of participants, organizers and audience members; digital political economy, by exploring questions of copyright and fair use for spoken audio materials in a digital environment; the creative dissemination of archival materials publicly through the organization of multi-media events and readings that integrate audio from the collection into live performance; digital presentation (or digital archiving), including decisions concerning the selection of a CMS, data structuring, coding for audio navigation, sound visualization, and the integration of useful ways to analyze the form and contents of the audio and visual files organized within the site; and (speaking of the micro) the articulation of basic principles of audiotextual criticism, that is, the necessary principles of bibliographical and textual scholarship in relation to a corpus of audio recordings that documents a reading series.

Each framing can itself be broken down into a further series of complex avenues of research and development and, of course, the methodological fabric of each frame can be woven across and into others to create increasingly thick, synthetic situating structures. To focus on the “micro” consideration of audiotextual criticism: our experience of documenting a poetry series has amplified for us the importance of what Jerome McGann stresses as the philological imperative that should inform our engagement with the “Digital Condition” that is replacing our historical “Textual Condition” (or, in the case of our immediate discussion, our “Audiotextual Condition”).8 As McGann argues, much twentieth-century criticism retreated from the sociohistorical approach to texts he identifies with philology in favor of “various ways for treating social and historical factors as interpretive constants rather than complex variables.”9 Assessing the implications of this trend at present, he articulates a critical imperative:

The need to migrate our cultural heritage to a digital condition has exposed the serious limitations in such an approach to the study of our cultural inheritance. The historical record is composed of a vast set of specific material objects that have been created and passed along through an even more vast network of agents and agencies. The meanings of the record – the interpretation of those meanings – are a function of the operations taking place in that dynamic network. Only a sociology of the textual condition can offer an interpretive method adequate to the study of this field and its materials.10

The digitization of archival audio therefore comes with its own set of problems for the audiotextual critic who attempts to meet this imperative while engaging and confronting the migration of the record across historical frames and media formats. Charles Bernstein addresses some of the issues in his “brief manifesto for the PENNsound archiving of recorded poetry” when he asserts of the digitized audiotext: “It must be named”, “It must embed basic bibliographic information”, and “It must be indexed.” Perhaps more controversially, the mini-manifesto also insists that “It must be singles”, that is, full length readings should be broken up into “MP3s of song length poems.”11 Bernstein’s call for informative file naming, basic metadata and useful indexing is crucial as more materials find their way onto the web. Poetry recordings that free-float on the web without such information can certainly still be enjoyed, analyzed and played with. They can still inspire works of criticism and art. They are certainly situated within a fascinating and dynamic new media environment. From the perspective of the sociohistorical audiotextual critic, however, which is the perspective of SpokenWeb, unattested recordings do not suffice unto themselves.

Audiography, or Reel Archaeology

Our experience has asked us to register the difference of audiotextual analysis even as it extends philological practices and routines into the domain of recorded sound. But rather than book covers, we read tape boxes. In place of paratextual elements, we find sound signals and extra-poetic speech. Our indexes include time-stamps and recording speeds rather than page numbers and edition counts. What started out as bibliography cleaves and becomes audiography.

And even for a collection of tapes as well documented and coherent as those comprising The Poetry Series corpus, the task of audiography is excitingly complex (notice, we don’t say “daunting”). For example, the tapes were made by the newly established SGWU Instructional Media Office (IMO), which was in charge of campus audio-visual (AV) media and facilities. That is to say, unlike so many recordings of similar kinds of readings and events from this period, The Poetry Series recordings were not made by poets, audience members or organizers, but by an office of the institution where the readings took place. Immediate benefits of this fact include very good sound quality across the corpus (with a few exceptions), and basic (yet inconsistent) cataloguing data that was standard protocol for the IMO. This institutional genealogy persists with the “re-discovery” of the tapes, as the originals are now stored and handled with established archival procedures aimed at their long-term preservation. At the same time, even this statement is complicated by the fact that, as we gradually learned, there are in fact two different sets of tapes of The Poetry Series, the originals made by the AV office, and a set of duplicates made for The Department of English, some transferred at different tape speeds, or to differently sized reels, thus creating different “breaks” across two sets of ostensibly “original” audio tapes.

A complete account of the various migrations The Poetry Series tapes went through, from the first AV reel-to-reel recording, to dubbed tape transfer, to dubbed digital transfer into WAV files on CD, to the conversion of the WAV files into mp3 format, and the migration of those files to large storage hard drives, tedious as such a story may sound, is being constructed and chronicled. Some of the basic observations accumulated in the process that are worth noting12 :

The collection of tapes consists of 82 “original” reels of audiotape identified as “AV” tapes, and 36 reels of duplicated tapes marked “English Department.” There are two reels in the English Department duplications collection that do not appear among the collection of original AV tapes. One is a non-reading series recording made by George Bowering from his home in British Columbia in 1967, prior to his arrival at SGWU, possibly an audition tape for the Writer in Residence post he would soon take up. The other is the recording of George Oppen reading at SGWU on October 25th, 1968, the date indicated on the tape box and the reading series poster, although the Gazette newspaper lists the reading as having occurred on March 8th of that year.

Only the English Department tapes have RT numbers on their boxes, which suggests that only those copies were made available for borrowing from the university library. All of the spelling mistakes of author names seem to appear on the AV tapes and tape boxes only, not on the English Department duplicates.

Only two of The Poetry Series recordings were made in stereo, those of Charles Simic and Gary Snyder. The rich sound quality of those recordings is immediately noticeable. Because they did not use a second track in the opposite direction to store further audio, each of these recordings required more than a single reel of tape (Simic’s recording used two 5-inch reels; Snyder’s recording used four 5-inch reels).13

When the digitization of the tapes was contracted by the University Archives, a mixture of original AV tapes and English Department duplication tapes were used. It is not yet clear why this hybrid approach to the tape selection was taken. Consequently, what is on the SpokenWeb site reflects this same mixture of categories.

Other fun facts concerning the relationship between tape and digitized audio:

Tapes from sixteen readings were divided into two parts during the digitization process because the length of a digital CD (74 minutes) was not sufficient to accommodate the sound stored on a tape using two mono tracks.

Three of these readings had been transferred onto three CDs from two tapes. These divisions have since been sutured with the move from CDs to hard drives. On the other hand, four of the audiotaped readings were combined from multiple tapes to single CDs.

The two readings recorded in stereo (Simic and Snyder), which took up two tracks in one direction on multiple reels of tape, did not take up extra space on an audio CD. The four Snyder tapes and two Simic tapes fit comfortably on a single CD each.

The goal in this part of the introduction is not to make an argument about The Poetry Series tapes based upon such information, but to point out just how much there is to know about the basic material, media migration and circulation history of such artifacts. These details are provided to incite future audiotextual scholars to ask, What do I know about my tapes? (Or, what do I know about my wax cylinders, vinyl flat discs, digital audio files, as the case may be?) The development of such an account has required the examination of extant paper technical documentation connected with the tapes, technician’s memos, cataloguing records, and, especially, the tapes and tape boxes themselves, which are both informative and enigmatic. It is, in part, to signify our investment in such audiographical work that we have used scans of Poetry Series tape boxes to define the art style of this special issue of Amodern. A complete set of scans, documenting front, back and sides, is available on the SpokenWeb site.

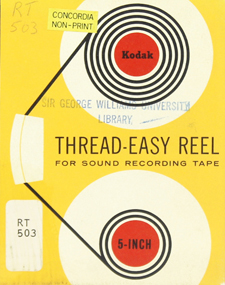

The label on the back of one such cover (Image 1) tells us it contains a reading by Phyllis Webb with (really it should read, and) Gwendolyn MacEwan that took place on November 18th, 1966. It is nice to have dates and names delivered to us on a platter (or reel box) in this way, as details are not always so easily discoverable. Having dates and names orients our search for further documentation of the reading in campus newspapers and other print sources, and helps establish the position of this reading in a series chronology, in relation to other readings and events in the lives of Webb and MacEwan, and in the wider world. The label provides recording details as well, both tape speed (3.75 ips) and the fact that the reading was recorded half-track (as we can glean from listening to it in mono). Because these tape covers are institutionally scripted, they are more technically informative than the labels of many homemade recordings from the same period. At the same time, they lack the often quirky, intriguing and individualized kinds of labeling systems devised for tapes held in personal or community collections.

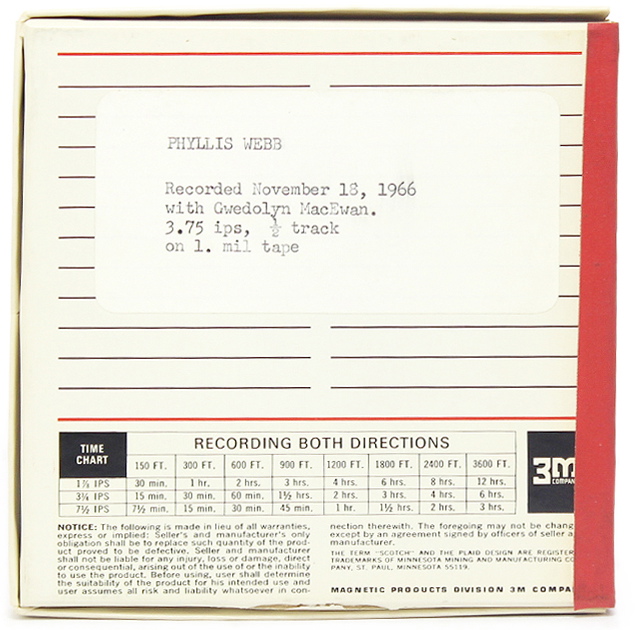

Some of the labels in the collection (not all of them) include a further note, in red typewriter ink, ALL CAPS, that states “Permission from Howard Fink to Reproduce This Tape.” Why would some of the tapes require the permission of Howard Fink (one of the key organizers of the series) for reproduction, and others not? (Note, also, the misspelling of “Alan” Ginsberg’s name – another symptom of having labels produced by AV technicians and not English professors.)

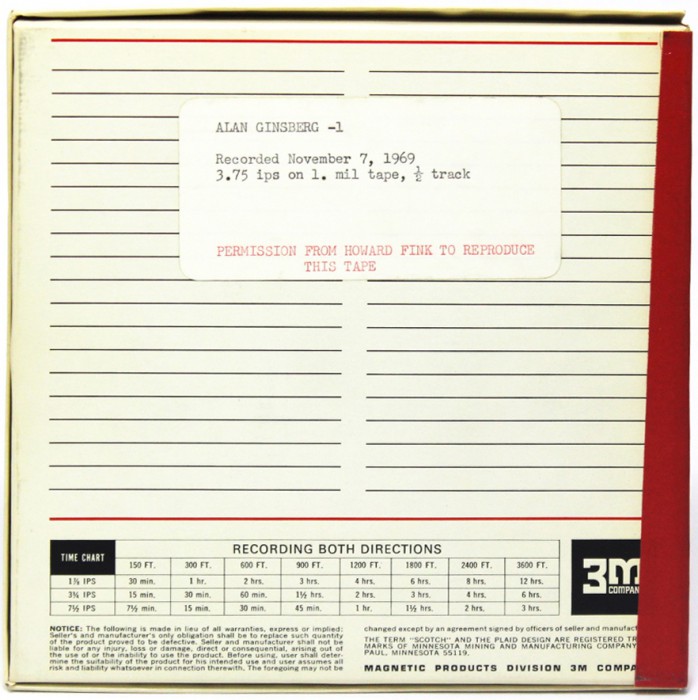

Still others are marked in pen, apparently by different hands, declaring “duplicate” or “FINK’S,” suggesting that series organizer Howard Fink had duplicates of some of the readings made for personal use. In an interview with Fink about the series, Camlot asked how the tapes were made, duplicated, edited, etc. While Fink had a wonderful memory for how the series began, for some of the readings themselves and the poetry parties, he remembered nothing about the recordings and the recording process.14

Further, some of the tapes are marked “Master” and others are not. What does “Master” mean in this context? Does it refer to the original, unedited version of the tape – a master version from which to make duplicate copies? Or, in tune with the more typical use of the term by audio engineers, does it signify a better balanced and possibly edited version of the original recording – a tape that has already been subjected to post-production?

Some of the tapes are marked “copy” (Image 4), an enigma we have rendered somewhat less opaque by speaking with former AV technicians, and through a careful examination of the entire collection of tapes and tape boxes. Christine Mitchell’s research, for instance, has revealed that tapes from the series were held in the “Sir George Audio Tape Library and Laboratory,” overseen by SGWU’s Centre for Instructional Technology (or CIT, as the IMO was re-dubbed in 1970). Duplicates of these, it seems, were then supplied to the Norris Library. This tape library, however short-lived, was housed in one of two new language laboratories, set up for students to listen and work through tapes individually in cubicles and for teachers to monitor students from a central console.15 Professors were invited to make their own tapes for pedagogical purposes in the language laboratories, with the supervision of CIT staff and according to its production standards.

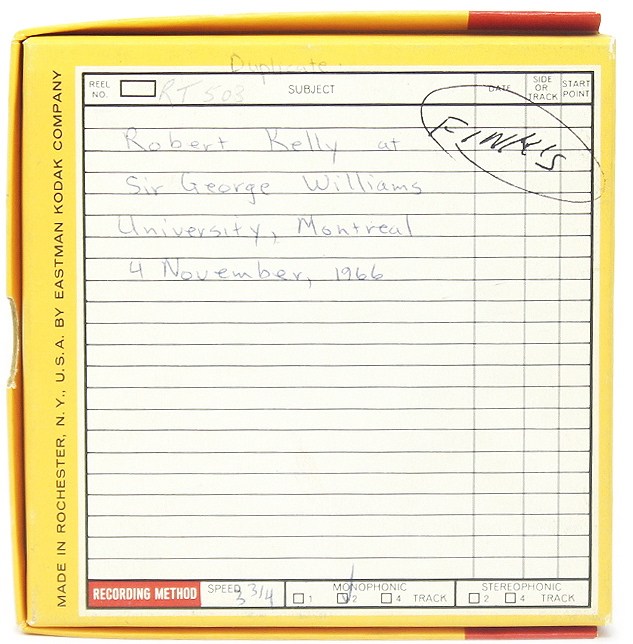

Some boxes retain the stamp of the SGWU Library, Concordia “non-print” stickers, and basic library Reel Tape call numbers (e.g. “RT 501” in Image 5), indicating that they were made available through SGWU’s Norris Library, then via the Concordia Libraries non-print materials desk, before being de-accessioned and removed to a top shelf in the office of a professor in the English Department.

The tapes themselves may ultimately provide additional insight into basic questions around production and use. Take, once again, the Allen Ginsberg recording. If you examine the transcript of Tape 1 on the SpokenWeb site, or listen to the audio file, you will encounter four (audible) instances of cutting or editing at the following timestamps: 00:16:38, 00:18:55, 00:41:37, and 00:49:28. Were the edits made on site during the reading or after the fact in post-production? When the original tape is examined, one finds lengths of white splicing tape between segments of brown recording tape. In this case, there are exactly three splicing-tape interruptions (not counting the leader tape at the start and end of the spool).

Thus, three of the cuts were made by splicing the tape and the fourth, less conspicuous edit was made by pausing the tape – either during the reading itself or during a dubbing reproduction process. The first post-production splice comes after nearly seventeen minutes of Hare Krishna chanting, probably cutting out audio that recorded the Krishna devotees’ departure from the stage in preparation for the reading to begin. Of the two remaining spliced edits, one came after the reading of “Angkor Wat,” a fairly long poem, and another just prior to Ginsberg’s singing of Blake’s songs, possibly accounting for the time necessary to set up the poet’s harmonium. Here is how those three leader tape edits sound, and how they look, as visualized with Audacity’s waveform:

Image 6: Three Leader Tape Edits Visualized in Audacity

The pause edit comes just a couple of minutes after George Bowering’s introduction of Ginsberg, and following Ginsberg’s own brief introduction to “Angkor Wat” (at Bowering’s request). It sounds and looks like this:

Image 7: Dub or Pause Edit Visualized in Audacity

The Ginsberg reading therefore manifests two kinds of editing, one that involves stopping and restarting recording during the event itself, and one that actually removes audio from the event in post-production and leaves it somewhere – possibly and quite literally on the editing-room floor. SpokenWeb researchers are still working out answers to such questions as who made these edits and why. According to information gathered through interviews with Howard Fink, George Bowering and Stephen Morrissey, we know that the Ginsberg event lasted over three hours. This fact alone may provide one plausible rationale for all the cutting. Christine Mitchell’s look into the history of instructional media at SGWU has thus far confirmed that all of the edits, spliced or not, were made by IMO / CIT staff members or student employees.

Printed labels, play speeds, call numbers, hand scrawled directives for duplication, the ink stamps of institutional units, visible and audible evidence of splices and dub edits – each and every one of these audiographical details exists as an emblematic, material trace that incites a question about the handling, storage, circulation and uses of our audible cultural heritage. As laborious and geeky (geeks being the new monks) as these kinds of questions may seem, and as difficult (or impossible) it may prove to answer them all, a commitment to audiography, understood as the relentless will to investigate and document the media and institutional contexts of literary recordings of all kinds, will help us establish some of the most basic, foundational facts concerning the literal production, post-production, reproduction and continuing uses of literary sound.

Audiography, comprising documentary and phonotextual investigation and outcomes, can thus be considered a variety – or fusion – of media and literary historiography, and provides both foundation and stimulus for the critical analysis of literary recordings. In the case of SpokenWeb, such hands-on decipherment has not only provided (and will continue to provide) important insights into the use and reuse of The Poetry Series tapes, but is necessarily and usefully pursued in relation to a variety of other framings and critical engagements with poetry series and poetry recordings that are assembled and presented in this special issue.

The Poetry Series: A User’s Manual

This special issue of Amodern on The Poetry Series is, in effect, presented as a complement to, an extension of, and a user’s manual for the wide-ranging activities and research efforts of SpokenWeb described above. It probes “the poetry series” as a literary concept from the macroscale as it reconstructs and reframes The Poetry Series through critical phonotextual, historical, political and material analysis that is rendered possible through that microscale compendium of audiographical findings, and which contributes to it in turn. In other words, the contributions in this special issue orient themselves around The Poetry Series as a specific iteration of poetry series in order to grapple with and develop theses and theories in response to such meta-level questions as: how can a poetry series be archived? where are its boundaries? how should poetry reading series be critically examined? how do individual readings relate to the whole series, and how do individual poems relate to a reading in its entirety? what is the organizing principle of the series – the calendar, the school semester, the funding season, the organizers’ whim, “set theory”? what range of tools – methodological, critical, digital – might literary scholars and historians use to examine poetry series? what is gained and lost when poetry series are digitally reconfigured, migrated, transposed?

Indeed, several of the contributions are outgrowths of the “Approaching the Poetry Series” mini-conference organized by Jason Camlot and Darren Wershler, held 5-6 April 2013, that employed The Poetry Series and its digital migration as an initial thought experiment and a template for conceptualizing and working with small p, small s poetry series. That gathering registered the challenge with an aphoristic piece by the organizers, circulated prior to the meeting as “Discerning the Reading Series” (and reproduced here in slightly altered form as “Theses on Discerning the Reading Series”). This provocative document enumerates and samples approaches to understanding poetry series, underscoring the relative risks and advantages of seeing poetry series not only as literary happenings, but as media productions. Camlot and Wershler’s basic argument is that understandings of the literary stand to be greatly enhanced, as well as productively undermined, by the still-unfamiliar recognition (via confrontations with recorded poetry performance) that poetics are necessarily media poetics, and that literary histories are necessarily media histories.

As an organizing principle, participants discovered, the “series” is productive, even where it registers only a vague – even random – contingency between analytical framings. Where does the poetry series derive its unity if not from the mere fact of its seriality? Its line-up-edness? The unity of the present issue of Amodern shares this haphazardness – its articles are not straightforwardly complementary, but are necessarily so. No treatment of an individual reading is possible without some consideration of the conditioning principles explored in another paper. That is our contention, indeed, our assertion, as audiotextual critics. For instance, Muriel Rukeyser’s politically inflected interaction with the Montreal audience is co-incident with the relative flow of funding for poetry reading series across Canada by the Canada Council. Consequently, Cameron Anstee’s article speaks to Jane Malcolm’s, and vice versa. The analysis of that Rukeyser reading, similarly, does not happen without the establishment of an Instructional Media Office on the SGWU campus and the routines by which it operates its sound recording equipment, the story told by Christine Mitchell. Oral history interviews and re-readings with organizers, poets, audience members and technicians, as well as broader political and social contextualization, as oral historians Ashley Clarkson and Steven High demonstrate, support and expand understandings of a series documented on individual reel-to-reel tapes and made audible as a unified, digitized set.

These interrogations do not just point inwardly and provide internal support, but bring the SGWU Poetry Series into dialogue with other literary spheres and institutional narratives. Gregory Betts interrogates the particulars of the SGWU series by intertwining its development tale with details of other literary publications, events and movements. Adopting a cross-country and intergenerational perspective, Betts argues that the shape, poetics and purpose of the Montreal series cannot be appreciated without an understanding of the Vancouver poetry scene and its own aesthetic debates, which so clearly inform large swatches of the series held at SGWU. Similarly, Dean Irvine’s account of Earl Birney’s reading at SGWU of a single, short computer-generated poem cannot be realized without broaching the much larger topic of the relationship between the research “Lab” in the 1960s and its implications for the future of contemporary creative and critical practice in the arts and humanities. While The Poetry Series was built around performances by major North American poets, the contributions in this collection and its expanded orientation to just what made and makes The Poetry Series brings to light other individuals, collectives and conditioning forces that have had a hand in shaping and re-shaping such events: audiences, literary critics, sound technicians, university administrators and professors, funding agencies and technical media.

Accompanying the audiography of The Poetry Series are contributions that forge a new kind of phonotextual practice, one that doesn’t attend to literary sound recordings simply as sounded text, but grapple with its specific features, formats, and immediate situations, analytically and critically. Danny Snelson’s remix mobilizes sound recordings themselves as commentary and critique, not relying on transcripts or audio quotations as examples in support of text-as-usual. Two contributions that deal with the same reading by Jackson Mac Low at SGWU demonstrate just how productive phonotextual critique can be. Brian Reed discovers and traces specific performative protocols in Mac Low’s directorship of “The Bluebird Asymmetries,” a collaborative work, and mobilizes this reading to argue that Mac Low embeds a kind of spiritual and voluntary social programming into his performance work. Michael Nardone takes his directive towards phonotextual practice from Mac Low himself, instructing critics to do what might seem obvious when confronting literary recordings – “Listen! Listen! Listen!” – but which, he argues, is nevertheless far from routine practice in critics’ continued reliance on texts. Al Filreis glances beyond the SGWU series to reading series more generally to engage and foreground close listening by interrogating “phonoparatextual” elements as features of liveness, and by recognizing specific poet-audience interactions as incitements for poets to perform differently, unsettling conceptions of poems and poetry readings themselves.

With Nardone’s directive, coupled with the considerations brought up in the roundtable conversation between Al Filreis, Steven Evans and Jason Camlot (a reworked transcript of a recorded panel discussion that took place at Yale’s Beinecke Library on April 26, 2013), we have steps towards a theory of listening and sound archives to be applied in literary analysis and pedagogy. Deanna Fong’s detailed classification and characterization of varieties of literary sound archives promises to help multiple communities of practice orient themselves around these formations, and is a valuable descriptive and critical tool for scholars and web designers in building advantageously for critical sound, visual, literary and audiographical practices going forward. In a similar vein, Christine Mitchell’s conversation with media theorist and archaeologist Shannon Mattern probes and anticipates practical and conceptual trouble-spots and opportunities for literary and cultural scholars embarking on media historical and archival work. An audiography that is as sociological as McGann recommends demands such practical guides, creative discussion, debate and ceaseless fine-tuning.

Each one of these stories, emerging from a grounded consideration of documented aspects of The Poetry Series reflects back upon and illuminates the particular Series from a unique angle, and contributes to our greater understanding of the poetry series in a more general sense. By probing the insides and edges of The Poetry Series, therefore, the articles in this collection participate in its collaborative and ongoing reconstruction, and reverberation.

Mark Schofield, Interview with Christine Mitchell. September 12, 2013. 00:42:53. ↩

This is not to say that The Poetry Series isn’t without its own stories of loss. In 2003, all of the paper correspondence that had been exchanged between Stanton Hoffman, an organizer of the series, and The Poetry Series participants had come into the hands of a former student of Hoffman’s, as heir, upon Hoffman’s death. These letters, which might have provided a rich contextualizing frame for the series, sat in a bankers box in the heir’s father’s garage in Montreal for seven years while the student pursued a teaching career in Japan. In 2010, the heir’s father moved from Montreal to Toronto. Called into town to empty out his father’s garage, the heir returned from Japan and proceeded to discard the entire collection of letters. Camlot learned this story when he contacted the former student in 2011 to ask if he might have the letters in his possession. Had Hoffman’s former student known he could make a deposit of a deceased professor’s effects to the University Archive, the letters might have been saved. As it stands, we are left with a story of unfortunate timing, and an empty space in our documentation of the series that ultimately leaves much to the literary historian’s imagination. ↩

Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word (Routledge, 2002). ↩

See, for example, Linda Shopes, “Transcribing Oral History in the Digital Age,” in Oral History in the Digital Age, edited by Doug Boyd, Steve Cohen, Brad Rakerd, and Dean Rehberger (Washington, D.C.: Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2012) <http://ohda.matrix.msu.edu/2012/06/transcribing-oral-history-in-the-digital-age/>; Dennis Tedlock, The Spoken Word and the Work of Interpretation (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983); and, an for an early voice in this discussion, Raphael Samuel, “Perils of the transcript,” Oral History 1 (1972): 19-22. Samuel’s argument focused on the “decadence of transcription” in relation to the “integrity” of the original speech, whereas more recent approaches consider transcription as part of a wider process of collecting and curating memory in multiple media formats. ↩

See, for example, David Antin, talking at the boundaries (New York: W.W. Norton, 1976); Jaap Blonk, Traces of Speech = Sprachsupren (Berlin: Hybriden-Verlag, 2012). ↩

Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain’s Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk (Grove Press, 2006); Victoria Stanton and Vince Tinguely’s Impure: Reinventing the Word — The Theory, Practice and Oral History of Spoken Word in Montreal (Conundrum Press, 2001). ↩

Murray and Wiercinski, “Looking at Archival Sound: Enhancing the Listening Experience in a Spoken Word Archive,” First Monday 17 (2012). ↩

Jerome McGann, A New Republic of Letters: Memory and Scholarship in the Age of Digital Reproduction (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2014), 23. ↩

McGann, A New Republic, 21. ↩

McGann, A New Republic, 22. ↩

Charles Bernstein, “Making Audio Visible: The Lessons of Visual Language for the Textualization of Sound,” Text 16 (2006): 287-88. ↩

These statistics and observations exclude details from an additional set of reels that were very recently located in the archive, comprising recordings from the series’ final year. These reels and related information will be added to our account in the future. ↩

To give a sense of the storage capacity of the tapes we are discussing: at 3.75 ips (inches per second), a 5-inch reel holding 900 ft of tape could store 45 minutes of audio in one direction, a 7-inch reel holding 1800 ft of tape could store 90 minutes in one direction. If the recording was done in mono using two tracks (one in either direction), a 7-inch reel could hold as much as three hours and twelve minutes of audio. See the time chart in Image 1 for further details. ↩

Howard Fink. Interview with Jason Camlot. SpokenWeb. November 2, 2012. ↩

“List of Audio-Visual Facilities Available for Instructors: 1970-71.” Concordia University Records Management and Archives. Principal’s Office fonds. Box HA 1591, Folder: Centre for Instructional Technology, 1962-1974. ↩