Cogs & cogs that cannot turn

to recognitions: such dogs in the dark noonday!

As if the tongue told & tolled

Among

the melancholic arcades.

Where the moods advance toward the modes.

Time to try the knot, the Not

Or to be caught

Forever in the nerve-traceries of Beauty…

Unstrung, the structure is sound.

–Andrew Joron, “Mazed Interior”1

I begin with “Mazed Interior” because the interplay of sounds and meanings in Joron’s poem – the resonant shift from “told” to “tolled,” “the knot” before “the Not,” the mechanisms of individual recognitions advancing toward utterance, moods molding into modes – opens up a space to hear Jackson Mac Low, his “simultaneities,” his “word event,” and, with Mac Low, approach the architectonics of noise his works make audible. Unstrung, the structure is sound. Here, one comes to sound as noun, sonus, an utterance, but one “unstrung,” sent forth to reflect, refract, echo and overlap, from all and in all directions, amid an architecture, within the ear. It is a structured, yet fugitive sound – as Edison termed it listening to his new invention, that captivator of noise, the phonograph.2 There, too, is another sense of sound: sound as adjective, from the Old English-Germanic gesund, health or healthiness, free from defect, as in of sound mind, sensible, sound judgment, of substantial or enduring character, as in: this unstrung structure, as such, will hold, shall persist.

It is from within these protean constructions of sound and sense that I want to begin this listening of Mac Low’s 1971 performance at Sir George Williams University (SGWU) in Montreal. The earliest recording of a performance presently available by the American poet, composer, and multimedia performance artist, the 1971 phonotext presents an entirely undocumented mode of Mac Lowian composition. No other recording of Mac Low captures the breadth of his compositions from the mid-1950s through to the early 1970s, and no other presents his extensive use of phonotextual materials in performance. In this essay, I trace out these undocumented aspects of Mac Low’s phonopoetics through a close listening of the performance that always keeps in mind the wider contexts in and through which these compositions make noise. Here, I pursue the ways in which Mac Low’s sonic architectures resonate aspects of his moment’s soundscape – of the Vietnam War, counter-cultures, mass protests and mass media – as he performs a “critical remixing”3 of his own personal archive of sounds.

Widely recognized for systematic chance-operated works and deterministic non-intentional compositional methods, Mac Low explored throughout his life a number of text-generative tactics: scores for happenings, Fluxus-styled language events, diastics, and other chance operations governed by tools such as the I Ching, action cards and dice. Steve McCaffery writes:

Mac Low’s systematic-chance-generated compositions impress most perhaps in their consistent emergence out of a variety of austere programs that emphasize the traditionally negative or countervalues in writing: semic dissonance, grammatical transgression, the elimination of a conscious intention, the removal of the writer as a centered subject responsible for the text it “writes,” a suspension of the word’s instrumental functions, and a provoked absence of the subject from the productive aspect of semantic agency.4

Ron Silliman suggests that the aleatoric compositions for which Mac Low is largely known make up a smaller part of Mac Low’s overall importance. As Silliman explains, “Mac Low was more or less alone in the 1950s in his explorations of poetic form as system (to my mind a far more important implication of his work than his use of chance operations, which are merely one type of system).”5 Charles Bernstein, noting Mac Low’s “architectural imagination,” considers these systematic explorations as “a practical catalogue of what writing can do.” Bernstein continues:

In effect, his work has broadened the possibilities of the medium, and as a result what can be done with it, by turning up syntactic patterns and textures that a less systematic and more traditionally expressive writing practice could not have. In the end, new terrains are made not just for structural and programmatic writing but for all writing and all reading.6

Entering upon “new terrains,” Bernstein’s discussion of Mac Low’s compositional experimentation switches its architectural analogy for an ecological one. Bernstein writes:

I think this may help explain why Mac Low’s voluminous persistence is so crucial to his project, even in the face of a reader’s exasperation at the “unevenness” of the work, his refusal to “edit” out the “best.” Such an idea would presumably strike Mac Low as oddly as it would a natural historian criticized for gathering too many specimens. (Note, in this regard, Mac Low’s meticulous insistence on documenting the system, conditions, and time of each work: a framing that suggests what his sense of a text is.) Indeed, Mac Low can be seen as a natural historian of language, investigating the qualities and properties of human being’s most shared substance.7

These considerations of Mac Low’s textual production provide the ground for the sonic dimensions of his compositional practice that I will consider in detail.

“The sound stratum of poetry,” writes Reuven Tsur, “is a continuous embarrassment for many literary critics.”8 Though I would argue there has been a significant shift in terms of attention to phonopoetical concerns even in the short span of time since Tsur’s statement was published in 2007, to a great extent his criticism continues to be true. Even though Charles Bernstein, as Louis Cabri writes, has been “largely responsible for the re-emergence of sound as a value for critical attention”9 in poetry and poetics throughout the last two decades, critical approaches to the phonotextual literary object remain largely unexplored. Even a poet like Mac Low, for whom sound was central to his sense of composition as a poet and composer, has had surprisingly little consideration given to the sonic aspects of his works in performance. The writings of Hélène Aji and Tyrus Miller are exceptions. Aji indirectly picks up on the architectural and ecological metaphors Bernstein developed above. She first notes the “architectural polyvalence” in the way Mac Low structures language to function in his poems, then focuses on the “transpersonal experience” of the poems’ performances.10 In outlining the intricate relationship between the page-text, the performed-text, the performers and the space of performance, Aji writes:

The specificity of Mac Low’s practice lies in the way he bases his work on the conception and execution of installations and processes that are not confined to their textual, visual, or musical dimensions but rather aim to redefine the poem as the integrated coexistence of all three dimensions to form the complete work.11

Mac Low creates structures, architectures, installations – yet they are processual, provisional, their materials perpetually shifting toward “integrated coexistence” with themselves and their surround. Tyrus Miller focuses upon the evental or situational aspects of Mac Low’s repertoire, and notes how Mac Low’s works in performance represent what Nicholas Bourriaud called a “social interstice,” a special, temporal site in the “arena of representational commerce” and a duration “whose rhythm contrasts with those structuring everyday life, and it encourages an inter-human commerce that differs from the ‘communication zones’ that are imposed on us.”12 In describing and theorizing the performative, intersubjective, political and paragrammic aspects of Mac Low’s oeuvre, Miller outlines how Mac Low “evolves a vast array of procedures to rotate fields of language” and how his “poetic procedures branch in several directions at once, offering the results as singular examples of a way of shuttling between language and the forms of life: a practical demonstration of how free critical and creative activity might be addressed to its environment.”13 Yet, despite the great care with which Aji and Miller articulate the performative and evental aspects of Mac Low’s repertoire (thereby always incorporating the stratum of sound), neither writer actually listens to the works. When Aji and Miller discuss the sounded elements of Mac Low’s works, they rely solely upon the scores for performance or other paraperformative materials: either the poem-text or the instructions for performance or reflections upon these texts. The omission of the phonotext in their work exposes a critical limit in textual scholarship as being unfit to engage the polvalent or pluriform qualities of a poetic work in performance. Each time Aji and Miller discuss sound in Mac Low’s works, they are writing about an abstraction of sound based upon what Mac Low intended as author and composer. Additionally, for all of the attention that Aji and Miller give to the specificity of Mac Low’s instructions for performance, they willfully ignore the imperative Mac Low pronounced on numerous occasions to be his primary admonition: “Listen! Listen! Listen!”

Mac Low, as much as any other North American poet of the latter half of the 20th century, deserves such a close listening. If anything, his unique sense of composition has always invited this participation, this kind of listening. In what follows, I heed Mac Low’s admonition and listen to the phonotext of his 1971 reading in Montreal. In doing so, I am interested in how the actual sounds that Mac Low orchestrated in performance, and the many contexts these sounds intone, allow for a richer understanding of the polyvalent systems of poetry he produced. My listening is guided by several questions: What does one gain, critically, by focusing on the sounds themselves in performance as opposed to the sounds as notated by the score for performance, or how might one best navigate both the performance and the score in relation to one another? What are the forms of listening involved in such a project? How and when does the object of criticism shift from the sounds to the performers to the spaces of performance to the technologies to the storage and transmission of the media? Where does the Mac Low performance end and the performance of the media begin, or, how are these always already integrated in the special case of Mac Low? In beginning to address these questions, I will transition from the ecological and architectural metaphors Bernstein and Aji take up in describing his works to the conceptualization of a soundscape and “aural construct” (to use Mac Low’s term) that he produces in his works. Here, I am particularly interested in how Mac Low orchestrates his own phonotexts to be collaborators in performance. Listening in detail, I discuss a number of things one might generally consider to be marginal to the works – introductions, conversations, interruptions, non-lexical moments, technological failures. I hear out how Mac Low organizes, and experiments within, particular sonic textures. Finally, I consider what implications this activity might have for developing an array of phonocritical practices today, ones that address the “continuous embarrassment” that Tsur notes above.

Moving toward the performance and its phonotext, some background on the event: Mac Low came to Montreal from New York in late March of 1971, the third year of the SGWU Poetry Series readings. The Poetry Series at SGWU (now Concordia University) marks, as Jason Camlot notes, “an important transitional moment in the history of English-language writing in Quebec” for bringing together a diverse range of poets from Montreal, throughout Canada and the United States.14 Roy Kiyooka, in his introduction to Phyllis Webb’s 1966 reading (also quoted in Camlot), describes the curatorial ethos of the Poetry Series:

[W]e have not attempted to make the series an exhaustive coverage of any particular school or faction of poetry. Nor has our concern been an attempt to seek out the so-called great poets. Our choices have been made with the desire to present to you, hopefully, the possibilities of utterance that is more than parochial. In short, this is our attempt to sound just that diversity that so much characterizes the North American poetry scene.15

In 1971, along with Mac Low, the series hosted Charles Simic, David McFadden, Gerry Gilbert, Dorothy Livesay, Gary Snyder, and Kenneth Koch. Of the recordings of this set of readings, Mac Low’s is unique in terms of its duration and the texture of its sounds. His reading is the only one that has no introduction. No person prefaces his performance with biographical information or publication history or personal anecdote. At 120 minutes long, the recording of his performance is the longest by far in comparison with the others from the series. Most readings during that year lasted around 45 minutes, though both Koch and Snyder gave extended readings, each around 90 minutes long. Finally, the Mac Low performance is the only one that has multiple readers performing at the same time, and no other reading involves instruments or reel-to-reel players as part of the performance.

To hear the difference in the sounded space of the series’ readings, it is useful to listen to an excerpt from the beginning of Charles Simic’s reading, picking up right after he announces that he will be reading “mostly from [his] third book, including, also, some more recent work.”16

“Vowels of delicious clarity for the little red schoolhouse of our mouth.” This singularly voiced poem of a commonly constructed syntax, of phrases kept in tension by a series of line breaks that are vocalized by specific pausing, uttered by an I who is presumed to apply to the I of the page-poem and the I of the speaker, read aloud following the poem’s progression as printed upon the page, this is exactly what we will not find in Mac Low’s reading. (This is to say nothing, for now, of the poem’s content.) Simic’s reading is a fine example of an approach to the poetry reading, as Peter Middleton describes, in which the textual meaning of the poem remains fundamentally unchanged in the reading and performance of the poem.17 On a sonic level, all of the paratextual comments and sounds remain distinct from the poems that Simic reads. Notice how pronounced the tone of the room is as separate from the atmosphere of the poem read: the door opening and closing as Simic begins to speak, the muted but constant shuffling of paper pages across the lectern, the closeness of Simic’s breath and the burst of each B-sound he speaks into the microphone, and the small stirs of sound that mark the audience’s shifting attentiveness. These noises register as distinctly other, discrete from the phonemes that are part of Simic’s poem. In these details, Simic’s reading is exemplary when compared to the rest of the 1971 readings. It is markedly different from the sounded space that Mac Low produces in his reading.

To hear the contrast, let’s listen to an excerpt from the Mac Low reading. This cut falls exactly at the middle of the recording’s two hours. The poem is one of his “Simultaneities,” though he does not offer its title during prefatory remarks. Instead, he states that the piece is multiple – “a number of these,” he says while introducing it – and describes them as “collages of various times and places, as well as the simultaneity in this room here.”

Mac Low describes the original text of this composition as “a piece produced by subjecting the electric typewriter keyboard to randomization by random numbers, so it looks like a lot of different characters from the electric typewriter.” Mac Low has instructed the performers of the poem to read from it “any way they wish.” The poem begins with the noise of the tape accelerating in its player – fast-forwarding or rewinding – as though that tape were the ribbon of a typewriter gone wild, mechanically spitting its characters all over the room. In doing so, the piece in no way tries to cover up or make transparent the various layers of amplificatory or recording technologies that are involved in the reading. Sonically, it’s as if Mac Low has gone into Simic’s “little red schoolhouse” of the mouth with a jackhammer to bust up the infrastructure of the ideological apparatus that is the articulating chamber of the unified subject.

Yet to hear these sounds more critically requires one to go deeper into the numerous audible layers of this phonotext and also into the textual documents that are of this piece’s constellation. As Aji writes, “These works’ intensity of existence comes from the fact that they reverberate from the moment of their inception onto other times and places.”18 Thus, for a deeper contextualization of this piece, one must trace out these reverberations. As is audible from the recording, the typewriter “simultaneity” is performed by a number of people, including Mac Low. Mac Low reads from the piece while manipulating four separate reel-to-reel players.19 Each machine plays a previously recorded performance of the “simultaneity.” On the first tape player, Mac Low manipulates an early performance of the the work that he made with musician and sound artist Max Neuhaus in a laboratory at the University of Illinois in 1966. On the second machine, he plays a recording of the piece performed together with Neuhaus, the composer James Tenney, and Jeanne Lee, a blues and jazz singer who performed with Abbey Lincoln and Anthony Braxton, amongst others. This performance took place at the Town Hall in New York in September of 1966. On the third and fourth players, Mac Low plays two separate performances he did at New York University around the same time as the Town Hall performance. During both of the NYU performances, Mac Low played each of the previous recordings of the performed piece: the first NYU performance has the initial Neuhaus recording and the Neuhaus-Tenney-Lee collaboration; and the second NYU performance has the Neuhaus recording, the Neuhaus-Tenney-Lee collaboration, and the first NYU performance. The roving contexts and overlapping combinations of the poem’s utterers and utterances – its accumulative and reproductive noise – assembles a multi-layered mesh of sounds, an ecology within which the performers must interact and tune themselves to one another however they see fit. In this, Mac Low takes to a particular limit the degree of intersubjectivity that Peter Middleton argues is always part of the poetry reading:

Audience and poet collaborate in the performance of the poem. […] During the performance the audience is formed by the event and creates an intersubjective network, which can then become an element of the poem itself. Intersubjectivity is only partially available as an instrument for the poetry to play, and is an ever-changing, turbulent process that can overwhelm or ignore the poetry, yet it is far from passive.20

In creating collaborative pieces that are structured for improvisation with members of the audience, Mac Low already emphasizes this intersubjective relationship in the time and space of the performance, radically so when compared to the example of Simic. Yet, he also extends that intersubjective experience temporally and spatially to other sites. Other performances, other performers, and other audiences are all sonically present, resonant in the Montreal performance of the poem.

From John Cage, we have a description of the program notes for the Town Hall performance of this “simultaneity.” Cage writes:

In 1966 a program of electronic music, electronic poetry, and live simultaneities by Jackson Mac Low, Max Neuhaus, and James Tenney was given at Town Hall in New York City. Printed in the program is “A Little Sermon on the Performance of Simultaneities.” There are seven admonitions (the 7th is a repetition of the first). Five of the six different statements propose silence. “1.) Listen! Listen! Listen! 2.) Leave plenty of silence. 3.) Don’t do something just to be doing something. 4.) Only do something when you have something you really want to do after observing & listening intensely to everything in the performance & its environment.5.) Don’t be afraid to shut up awhile. Something really good will seem all the better if you do it after being still. 6.) Be open. Try to interact freely with the other performers & the audience.21

Cage’s interpretation of the program notes is somewhat misleading in that what Mac Low proposes is not “silence” but an active engagement to hear – following Cage’s own explorations of the subject – how (the impossibility of) silence sounds. “Silence” is only one of the numerous possible occurrences for sonic production, a possibility that occurs always in the present moment of a poem’s performance and shifts with it moment to moment. Mac Low’s admonition is for the performer to not utter the text in any kind of previously scripted manner. The performer is to be attentive to the moment of collective performance, attuned to it in a practice of “active listening,” the kind that Pauline Oliveros has described as involving “interpretation, participation or meeting the stimulus with sensual, emotional, intellectual or intuitive energy.”22 The performer must be sensitive to the sounds produced by those surrounding, all the while maintaining an awareness of the total sound the group collectively produces. Describing his “Simultaneities,” Mac Low writes that

individual performers exercise initiative and choice at all points during the piece but are also – by listening intensely and responding to all they hear, both other performers’ and ambient sounds both within and outside of the performance space – constructing an aural situation that is not merely a mixture of results of egoic impulses, but an aural construction that has a being of its own.23

At the conceptual intersection of this intersubjective practice and Mac Low’s idea of “an aural construction,” it seems apt to note Bernstein’s statement that Mac Low was more interested in “building structures than in inhabiting them (leaving, that is, the inhabitation to performances – his or ours).”24 For Mac Low, this inhabitation of the poem takes place in the collective production of an aural – which is to say social – space, in its sounding.

With these aural constructions and their inhabitation in mind, I want to rewind back to the start of the Mac Low reading, to his first poem, “Glass Buildings.”

Again, following no introduction, no preamble, Mac Low begins his reading with a first tone into a lulling. His wood flute – the bamboo of a bansuri or possibly that of a shakuhachi – makes audible some past pastoral place, one across which this melody might have carried a distance. Then that lull accelerates into an audiotape’s hiss. “Glass Buildings,” spoken mechanically: it is difficult to discern, due to slight distortion, if this is Mac Low speaking into a microphone or a recording of his voice. “WHEN FIERY WATER THIRDS FLAUNT SOLAR FUSION.” With these first words, that pastoral past’s imagining of a future apocalypse becomes fused to the moment’s nuclear fears. Then: no big bang, but, instead, the lull of the wood flute, its melody moving in and out of each syllable’s pitch. Any line between what is uttered, embodied sound and what is timed instrumental manipulation – of the wood flute and/or the tape players – becomes blurred. Only those there could know, potentially. With this poem – “a calligramme & an attempt at expression by means of multiple ambiguity where all possible meanings are ‘meant’ by the poet”25 – a system of words extends through the soundspace, synched in a palimpsest, a palimtext of noise.

The mechanical clanking undergirding “Glass Buildings” continues into the next poem, one of Mac Low’s “5 biblical poems.” If one were not already familiar with the works, though, it would be difficult to discern any specific shift from poem to poem. There is no distinct audible sign to mark the shift into another poem, as one is generally used to hearing at a poetry reading. Mac Low offers no paratextual speech as segue. At a certain point he stops one reel-to-reel player – the thick click of it shutting off is audible – as another, probably several, begin(s) to play. Mac Low’s voice announces a set of numbers: 5, 2, 3, and the numbers continue. As those phonemes emerge, another voice – also Mac Low’s – overlaps and obscures this progression.

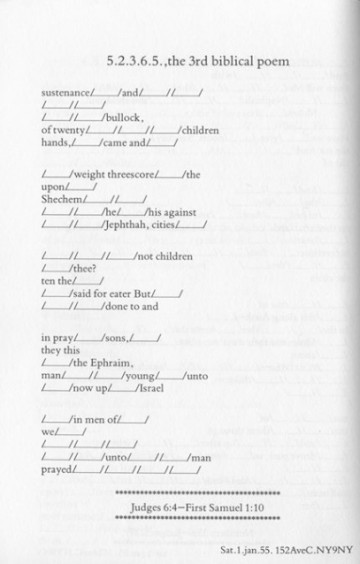

At one point, it sounds as though Mac Low calls the work “Syllable Poem.” This mishearing is productive for considering the poem. The “5 biblical poems” mark a major shift in Mac Low’s work in that they are his first poems organized by what John Cage called “chance operations.” In 1954, while working closely with Cage, Mac Low began to explore ways in which he could destabilize his authorial control over the production of a poem’s content. “Indeed,” Mac Low writes, “these methods and others first arose from an attempt to lessen (or even vainly to try to do away with) the hegemony of the ego of the artist in the making of the work.” In “5 biblical poems,” “the writer ‘translates’ the notes, rests and/or other features of the notation of a musical work ‘into’ words from some source text by either the writer or others.”26 The various numbers that Mac Low reads at the poem’s start relates to the number of “events” – sword or pauses (marked by an empty slot “/____/”) – that he accorded to each line in the poem. Mac Low determined these numbers by rolling dice, hence the term “aleatory” that he often used to describe this compositional method. Taking passages of Hebrew scripture as a seed-text – for this particular poem the passage is from Judges 6:4 to 1 Samuel 1:10 – Mac Low performed his chance operations to produce the text for his “5 biblical poems.” On a page, as a score, the poem appears so:

Image 1: “5.2.3.6.5., the 3rd biblical poem” from Representative Works, 1937-1965.27

There is a faint trace of a narrative here – the story of the inhabitation of Palestine by the Israelites, from Gideon’s defeat of the Midianite nomads through to the birth of the future king Samuel – but it is a narrative with great gaping holes for the reader/performer to respond to with an action, or a sound, or a silence. In producing a new text from this particular seed-text, Mac Low foregrounds the historically dynamic qualities of the Hebrew scriptures – its edits, insertions and erasures across centuries.

This textual dynamicism and variabilty has a sonic counterpart in that no performance of the text is ever repeatable as performance. Of course, no performance can ever be replicated – the temporal and spatial conditions are always different – yet the high degree of likeness between textual performance of the language upon the page and the vocalic performance of the poem’s language emerging from the poet’s mouth, of which the Simic poem above is but one example, is typical of the poetry reading. Mac Low accentuates the contingency of a poem’s performance in this case by adding additional readers and by including the various recordings of him performing different versions of the same text. Mac Low is playing with at least two reel-to-reel players here, and there may be two additional ones playing if the metallic clanking and the wood flute are on separate players. He begins to play the recordings at different times, and each recording starts at a different section of the poem. Additionally, Mac Low’s own reading and the recordings of him reading each have different pacings: the same word may be held longer or shorter in one version than another, and the length of the pause is decided upon by the individual reader while reading. What emerges from this asynchronicity of layers is, indeed, a “syllable poem.” With the narrative progression of the seed-text reinscribed as a schematic of individual words and pauses, the poem shapes a sound structure assembled from the array of fragmented utterances (from one to a few syllables) and (Cagean) “silences.” Even the unit of the single polysyllabic word gets broken up into smaller particles as other voices and other sounds overlap to produce a different total sound in performance. Listen, as but one example, to the word “twenty” at :50 into the recording: the overlap of “look” over the “twen-” and the mechanical clank immediately following the “-ty” produce two separate vocalic chords in which the two syllables of “twenty” resound in part. Note, too, how this instance of “twenty” sounds nothing at all like the word as it is uttered several other times during the poem. This difference is worth emphasizing simply because the structural indeterminacy that Mac Low engineers into his works extends through all the collective spatial and temporal constructs of the work, right down to its simplest elements, the syllable and the phoneme.

Then the tapes stop. From the din of the previous several minutes still present in the moment’s disquiet, a single voice emerges.

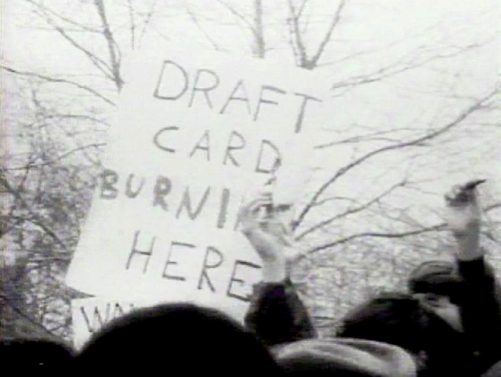

From the pastoral landscape evoked in “Glass Buildings” to the pastoral society of the Israelites embedded in the “biblical poem,” Mac Low shifts the aural atmosphere of his reading to a new terrain: the Sheep Meadow of New York’s Central Park. One arrives at this space not just at any moment, but a particular one – as Mac Low announces in the poem’s title – around noon, on the 15th of April, 1967. It is the day and specific location of the first large-scale burning of individual draft cards by resisters.

Image 2: Anti-Vietnam protest. Sheep Meadow, Central Park, New York. April 15, 1967.28

Exactly at the moment when an expansive atmospheric noise of numerous voices, one matched with musical instrumentation, might fit the form and content of a protest setting, Mac Low dramatically alters the sounded space of his performance. In “On the Glorious Burning of the Stars and Stripes,” a single speaker apostrophically attests in direct emotive speech what he witnesses: a scene of dissent that overwhelms him with its beauty. Mac Low declaims “How beautiful,” and repeats it several times – “How beautiful,” “How beautiful” – regarding the great mass of people gathered together and, amid them, “burning in the April breeze,” the US flag, “those bloody stripes that once meant freedom.” In the poem’s address, in its Ginsbergian use of anaphora, its language play on the metaphors of “sheep,” “peace,” “sea,” and its intentional manipulation of a symbolic language rooted in an historic US nationalism, this is the only time during the reading that Mac Low reads a text that one might easily recognize or categorize as a “poem.” It comes at a hinge moment in the overall reading. With “Glass Buildings” and the “biblical poem,” Mac Low constructed a temporally and spatially expansive soundscape out of which, for a moment, the voice of the individual poet emerges. Just as that individual voice comes into fruition, as it takes form, a din returns, a multitude of voices resumes its hub-bub. The poet returns to the common space – in this instance, importantly, one of dissent – that is the subject of this poem. From this point of departure, the poet continues to experiment with alternative configurations and expressions that will not only construct new poems, but also new modes of interaction within them.

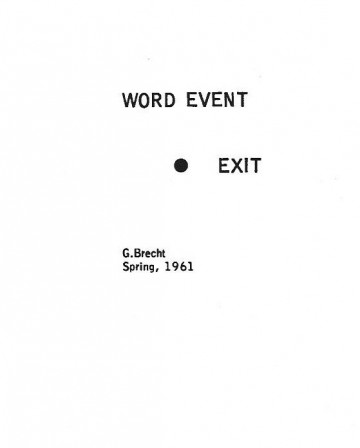

Mac Low’s “Word Event for George Brecht” is the transitional work that shifts the soundspace of the performance from an individual voice to a polyphony of voices. In the poem’s dedication to the Fluxus composer of evental scores, one is again reminded that Mac Low’s poetic compositions are in direct conversation with the works of New York City’s avant-garde music scene of the 1950s and 60s. Brecht’s own “Word Event” – a single page score upon which the only proposed action is “EXIT” – is a disquieting counterexample to the noise Mac Low summons in his own “Word Event.” In Brecht’s event, performers are implored to find some way out, to escape the time and space of performance.

Image 3: Score for George Brecht’s “Word Event,” 1961.29

In Mac Low’s “Event,” previous performances resound from their specific times and spaces to become fugitive in the present. Whereas the recordings played in “Glass Buildings” and “biblical poem” sounded out of an undefined past occasion, in “Word Event” Mac Low notes the specific occasion of the poem’s original performance that replays in the midst of this one. “This is a kind of poem that can be done on any words,” he states. “I did it first on these words at a reading in New York where the Russian poet [Andrei] Voznesensky joined some American poets at an anti-war reading.” Mac Low begins to play that performance on one – and, again, possibly several – of his tape recorders.30 The recording plays for nearly a minute before Mac Low begins to join his (live, embodied) voice to his recorded vocalization of the poem. Mac Low uses a seed-text of two words: “anti-personnel bomb.” All the utterances in this poem emerge from the letters of these two words. Bruce Campbell describes the process of “Word Event”:

On 4 November 1961 Mac Low composed his “Word Event for George Brecht.” In this scenario someone says a word and then analyzes it into successive phonemes and then into phonemes representable by its successive individual letters. Then “he orders phonemes from both series in random orders.” […] The “Word Event,” therefore, is about permutations and “performers making spontaneous choices” as much as it is about an event.31

As Miller notes of the poem’s instructions for performance, “the performer has the choice to determine the emotional tone and rhetorical pitch of this a-semantic poem.”32 This performance technique begins an exploration of language that Mac Low would employ in a number of works he would compose after “Word Event,” some of which are included in this performance. The poems from the “Asymmetries,” “Gathas,” and “Vocabularies” series each explore in their own way this kind of phonemic dispersion, textually and performatively. Again, for Mac Low, these “aural constructions” were opportunities for people to come together and experiment with how to speak and act differently with one another. He hoped that, as micro-social experiments, they might “change the ways that people use and perceive language,”33 therefore helping to chart out other possible forms of relations and mutual existence.

“Word Event for George Brecht” is particularly notable for the way it mimics the explosive fragmentation of the seed-text’s subject, the anti-personnel bomb, while also tapping into the affective states of shock the bomb leaves in its wake. The construction of this affective state begins in the human-machinic groan that comes through the audiotape players and the microphones and develops into a cacophony of syllables bursting beyond the machines’ bass frequencies: they resound as scattered bombing. Mac Low’s insistent repetition of No – “No, No bombs, No bombs on persons, No” – amplifies a sense of trauma that becomes protest, becomes prayer: “No bombs on persons. All bombs are anti-person bombs. No. Let it not be. Let no bombs be on persons. No.” The cacophony of the vocalic and machinic overlap – and the violence that noise intones as it coats and blurs each individual utterance – grows until it slowly subsides. As it clears, as the echo of that noise is still felt, a single voice reemerges with a stuttered “I–I–I” – the utterance of a fragmented subject, or one attempting to insist upon their singularity – then utters a final “No.”

In the remaining poems – a series of “Asymmetries,” the typewriter “simultaneity,” excerpts from his recently completed Stanzas for Iris Lezak, including “Poe and Psychoanalysis,” “Fifth Gatha” and “Bluebird Asymmetry,” and then, finally, a poem called “The” – Mac Low experiments with a number of arrangements for collective vocalic composition. At the core of the performances of these poems is Mac Low’s admonition that performers listen and relate to one another. Also at the core of these poems is a phonocritical practice that Mac Low adopts in order to integrate the recordings he has previously made into the present performance. He initiates this practice in his introduction to “Word Event for George Brecht” when he details the first performance of the piece, the reasoning behind it, and the context of its composition. As detailed in my discussion of the typewriter “simultaneity,” Mac Low takes great care to introduce the previous sites of the recorded performances, the contexts for the recordings, and the performers involved. He presents his personal archive of recordings not as some set of objects one simply takes in, but, like his poems, as opportunities for new interactions between people. Instead of being heard in a private space, say, by an individual listening with headphones, they are played in the public space of performance. Again, the admonition is to listen, to relate, however one can. This phonocritical practice situated within performance is a subtle yet important innovation that he maintains for the rest of the compositions in the Montreal performance until, reaching the final poem “The,” he interrupts his own explanation, turning to his collaborators to say, “Let’s just make it.”

I’d like to examine the next cluster of poems collectively, pausing on a few specific moments in the progression. Except for the initial sections from Stanzas, each one of these poems involves a number of performers in collaboration, involving somewhere between seven to ten performers. (It is worth noting that in introducing the initial section of Stanzas, Mac Low regards performing with the recording devices as a kind of collaboration, stating: “I’ll first read a short group solo and then read one in a duet with an earlier performance of it.”) Though these poems all have quite different textual layouts on the printed page, each one is scored in a particular way for individual performers to make the choice exactly when and what and how they will utter from the page-score during performance. To offer examples of the variety of textual design and materiality of these poems: “Asymmetries” is a work compiled from a series of 501 single-page performance pieces Mac Low wrote in the early 1960s; the early excerpts from Stanzas appear as though they were conventional prose poems; the typewriter “simultaneity” seems to have been written on various pieces of paper that the performers passed between each other; and the “Fifth Gatha” was composed on graph paper with each individual grid designating a letter or a blank space. Again, all of the poems – except for that initial section from Stanzas that Mac Low performs “solo” – involve the use of previously recorded materials delivered via audiotape players. Each poem, except for the final poem “The,” performs a specific act upon a seed-text that breaks the text up into individual letters, combinations of letters, discrete words, and particularized phrases. Finally, for all but the initial sections of Stanzas, Mac Low has designed each poem to be primarily a score for performance, though each is significant in a number of ways as a page-text in and of itself.

On a sonic level, any sounds – whatever noises – function as a part of these poems; they are included. The sounds become integrated into the site of the performance and they are also inscribed upon the (archival) chain of phonotexts and performances that follow. Mac Low has engineered all of these sounds and the possibility of all future sounds into the systems of the compositions. All the sounding bodies – human and non-human – play a role: the person who composed the poem and the people who perform it; the audience members who respond in some way, say, by their whispered comments or by moving their bodies however slightly or entering and exiting the room; the amplification system and its odd buzzing or moments of feedback; the tape recorders and the din of their fast-forwarding and reversing, their buttons clunking on and off; the architecture of the space itself and how it might reverberate such sounds and the heating pipes clanking or a window that is opened or closed; even the sounds from outside the window or beyond the doors – the overheard excerpts of talk between passers-by, the cars on the streets, the truck backing up or siren passing – they are always already incorporated into the sound structure of the poems. Mac Low has designed his sonic architectures to accommodate and to incorporate in advance of their occurrence such accidents and ambiences.

Moments occur like this possible technological fail or glitch:

Are these sounds actually produced in the midst of Mac Low’s reading? Is Mac Low making them? Is this an example of Mac Low mimetically playing back the sounds of his particular media ecology by including a radio test in the transition from one poem to another? Or is it an error? Does Mac Low accidentally press the wrong set of buttons on his reel-to-reel players and thus produce this noise?34 Perhaps it is an error made by the person who recorded Mac Low’s performance on behalf of the SGWU Reading Series. Maybe this strange bleep is simply an effect of the magnetic tape reel’s decomposition during the 40 years it remained in storage at Concordia University’s Audio-Visual Department. Or does the sound emerge from some error in the magnetic tape’s transfer into an MP3 digital format? All of these activities and all of these actors in their various times and locations need to be factored in – or acknowledged as impossible to know – when considering Mac Low’s overall performance. Mac Low has designed their participation, whether intentional or accidental, into the systems of these poems.

“What happens when the archive is literally transformed into a scene of performance and noise?” Kate Eichhorn asks in pursuing a poetics of archiving sound.35 How might one curate an archive of sounds in a way that addresses or somehow incorporates the evanescent dimensions of the sounds themselves and the performances or events from which they emerge? Mac Low – with his personal archive of audiotapes that document his performances, and his explorations of how others can relate and contribute further to the various trajectories of phonotexts and performances – offers an exceptional response to Eichhorn’s inquiry. As Eichhorn writes, “Sound is always coming undone, and so too is sound’s archive.”36 Mac Low sees this undoing as a positive, if not necessary, aspect of poiesis. For Mac Low, this undoing is one way out of “the little red schoolhouse” of the poet’s mouth, a way to not produce what Lyn Hejinian has called “an isolated autonomous rarefied aesthetic object.” To move away from this object and its reproduction, Mac Low cultivates a practice in which “aesthetic discovery is congruent with social discovery” and “new ways of thinking (new relationships among the components of thought) make new ways of being possible.”37 Here, I am intentionally blending the entities of “archive” and “poem,” as, for Mac Low, the former is emergent from the latter: the former part of the production of the latter, the latter reshaping the former. Both accumulate, and in their accumulation are rendered different. If, following Foucault, the archive is first the law of what can be said,”38 Mac Low’s compositions are systematic attempts to revise the archive – its “accumulated existence”39 – by means of the poem, therefore expanding what is possible, what is enunciable, in both.

It is with this sense of an accumulated existence and enunciability that Mac Low brings his Montreal performance to an end. Having moved from the first poems’ lull and babblings of “Glass Buildings” and the “biblical poem,” their simultaneous intonings of pastoralism and apocalypse, to the concern with a more contemporary apocalypse situated in the Cold War and the Vietnam War in “On the Glorious Burning” and “Word Event,” through to the polyvocalic collaborations of the “Simultaneities” and “Asymmetries,” Mac Low finishes his performance with “The” – at once an Edenic and end-times summoning of the contours of the earth, its creatures and spaces. It is for this poem that Mac Low, after a couple of digressions, abandons his own prefatory remarks. He initiates the piece by noting that he has “one last [poem] that none of these people have yet seen, and so this one has no rules.” Amending that statement, he checks to make sure the readers each have three pages from the text and then tells them: “Just use whatever discretion you want, and listen, listen, listen.” Having brought up his admonition to listen, he begins another brief digression with regard to the previous poems:

Earlier, I had very strict rules governed by chance operations and so on in reading these simultaneous works, and more and more I came to the, well, I always had the principle of the most important things was to listen hard to everything that was happening, including whatever was happening in the room, whatever’s happening outside and so on, but more and more I relied on the readers to judge when to come in and perform.

Here, Mac Low presents the prior governing principles as exercises to develop one’s ability to perform with and to relate to others, and especially to listen carefully to one’s environment. Then, with that experience, the performers can abandon the previous sets of governing principles while remaining mindful to the one rule essential to them all: to listen. It is at this moment that Mac Low abandons his own explanation of the poem, saying to his collaborators and audience, “Let’s just make it.”

Mac Low begins the poem: “The wind blows. The rain falls. The snow falls. The streams flow. The rivers flow.” Then a second voice joins in: “The mosses spore.” Mac Low responds: “The oceans rise. The oceans fall.” At once a number of voices enter. “The birds eat.” “The stars shine.” “The animals breathe.” “The flowers cross-fertilize.” The voices register at different distances from the recording machine. It sounds as though the performers are dispersed through the room, thus creating a surround-sound effect. “The trees grow. The plants grow.” “The fishes eat.” “The funguses spore.” By the occasional thunking of machine buttons and the slightly tinnish quality to some of the voices, one can hear that at least a few of the voices emanate from Mac Low’s reel-to-reel players. “The insects are hatched. The reptiles are hatched. The mammals are born. The birds are hatched.” Sentences repeat, though they are spoken by different voices. “The mosses spore.” “The stars shine.” Entire life cycles take place in the poem. They are articulated at different times by voices that overlap and echo one another. “The insects eat.” “The people travel on water by boats and ships.” Creatures are born; they breathe and eat and grow; they move their bodies and travel across great distances; they interact and mate; they die. “The animals eat.” “The rivers die.” “The lichens grow. The flowers grow. The trees grow.” The sentences are uttered loudly; they are whispered; they are shouted; the syllables uttered are staccato or a single phoneme is held over a duration; they are quickly run together one after the other. “The people crawl and swim and run and walk.” “The ferns turn toward the light. The plants turn toward the light.” “The planets shine.” “The people die.” “The trees sway in the wind.” “The earth turns.” Mac Low completes his reading with an assemblage of sounds, an indeterminate and polyvocalic inventory of simultaneous processes – biological, cultural, cosmological.

As opposed to a methodology that relies solely upon the text or score for performance, a phonocritical approach to the polyvalent or pluriform work provides a way to more comprehensively engage with the simultaneous processes involved in Mac Low’s poetic practice. It is a critical practice Mac Low himself exemplifies throughout this performance. His phonocritical approach does not limit itself only to the phonotextual object, but attends to the network of material and embodied interactions in which the phonotext plays a part. It adopts a plenitude of techniques to more thoroughly engage with what is inscribed upon the recording, the various social and aesthetic layers of an inscription, while figuring in the cultural techniques and contexts of the apparatuses that have enabled an inscription’s transmission and storage over time. With these techniques, one can investigate how each sound or combination of sounds recorded on the phonotextual object performs, uniquely and as textures. Mac Low acknowledges the existence of the various materials and actors that are part of a performance – the texts, phonotexts, technologies that play and record during performance, the performers, the audience, the site and context of the performance; he considers them collaborators. Mac Low demonstrates a certain responsibility to the various materials and actors: he takes great care to detail the particular structure of a work, its methods or instructions, its actors, and the contexts out of which the work emerges and is fugitive. These materials and actors do not converge in some abstract or idealized space, nor are they made transparent as part of the spectacle of performance. Again, he insists on the social space of the reading for this activity of listening and relating. This activity is not discrete from the performed work, but is a significant aspect of it. Traces of those listenings and responses then accumulate as part of the overall work, and are archived within it to be resounded in its continued performance. In these simultaneous processes of the poem, Mac Low enacts a phonopoetics in which the figure of the poet is not an individual speaker who utters forth, but one amid a multitude who listens, and responds.

Andrew Joron, Trance Archive: New and Selected Poems (San Francisco: City Lights, 2010), 78. ↩

Thomas Edison, “The Phonograph and Its Future” in Music, Sound and Technology in America, ed. Timothy D. Taylor et al. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 29. ↩

Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 11. ↩

Steve McCaffery, Prior to Meaning: The Protosemantics and Poetics (Evantston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2001), 187. ↩

Ron Silliman, “While Some are being Flies, Others are having Examples,” Paper Air 2.3 (1980): 39-40. ↩

Charles Bernstein, Content’s Dream: Essays 1975-1984 (Los Angeles: Sun & Moon Press, 1986), 254. ↩

Bernstein, Content’s Dream, 255. ↩

Reuven Tsur, Toward a Theory of Cognitive Poetics (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2008), 111. Quoted in Louis Cabri, “On Discreteness: Event and Sound in Poetry,” English Studies in Canada 33.4 (2007): 14. ↩

Louis Cabri, “On Discreteness: Event and Sound in Poetry,” 3. ↩

Hélene Aji, “Impossible Reversibilities: Jackson Mac Low” in The Sound of Poetry / The Poetry of Sound, ed. Marjorie Perloff and Craig Dworkin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 160. ↩

Aji, “Impossible Reversibilities,” 149-50. ↩

Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, trans. Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods (Dijon: Les Presses du Reel, 2012), 16. See also: Tyrus Miller, Singular Examples: Artistic Politics and the Neo-Avant-Garde (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2009), 40. ↩

Miller, Singular Examples, 46-7. ↩

Jason Camlot, “The Sound of Canadian Modernisms: The Sir George Williams University Poetry Series, 1966-1974,” Journal of Canadian Studies 46.3 (2010): 30. ↩

Roy Kiyooka, “Introduction to Phyllis Webb,” 18 November, 1966, SpokenWeb. Also quoted in Camlot, “The Sound of Canadian Modernisms,” 32. ↩

Charles Simic, “Poetry Series reading,” 19 November 1971, SpokenWeb. ↩

Peter Middleton, Distant Reading: Performance, Readership, and Consumption in Contemporary Poetry (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2005), 262. ↩

Aji, “Impossible Reversibilities,” 151. ↩

From Christine Mitchell’s conversation with Mark Schofield, archived on SpokenWeb, we know that Mac Low was most likely using several Sony TC-106 seven-inch reel-to-reel tape recorders and players. See here, the conversation beginning at 13:50 for Schofield’s description of the equipment that Mac Low used. ↩

Middleton, Distant Reading, 291. ↩

John Cage, “Music and particularly Silence in the Work of Jackson Mac Low,” Paper Air 2.3 (1980): 37. ↩

Pauline Oliveros, The Roots of the Moment (New York: Drogue Press, 1998), 24. ↩

Jackson Mac Low, Thing of Beauty: New and Selected Works, ed. Anne Tardos (Berkeley: University of California Press. 2008), xxxii. ↩

Bernstein, Content’s Dream, 257. ↩

Alan Filreis, Counter-Revolution of the Word: the Conservative Attack on Modern Poetry, 1945-1960 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 63. ↩

Mac Low, Thing of Beauty, xxxi. ↩

Jackson Mac Low, Representative Works, 1937-1965 (New York: Rook Books, 1986). Many thanks to Aaron Beasley for providing this scan of the poem. ↩

Screenshot from public domain newsreel, “Anti-War Demonstration In New York City,” Archive.org, accessed on 7 July 2014. ↩

George Brecht, Score for “Word Event,” UbuWeb, accessed on 7 July 2014. ↩

Also, we know from the diaries of poet Stephen Morrissey – and from Jason Camlot’s recorded dialogue with him on SpokenWeb – who was, at that time, a student at SGWU, that the multimedia component of the poem extended into the visual. Dated in his diary 26 March 1971, Morrissey describes the various materials of the performance space: “All sorts of tape recorders. A recorder which he blew sweet notes from. A projector. A film of Voznesensky with Allen Ginsberg in the background, also Gregory Corso. [Mac Low] read, mixed noise, and got a group of readers to come up and read simultaneously words. Just words.” Listen to Jason Camlot’s interview with Stephen Morrissey, 22 April 2013, SpokenWeb. ↩

Bruce Campbell, “Jackson Mac Low” in Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 193: American Poets Since World War II, Sixth Series, ed. Joseph Conte (Farmington Hills, Michigan: The Gale Group, 1998), 196. ↩

Miller, Singular Examples, 34. ↩

Mac Low, Thing of Beauty, xxxii. ↩

“Errors” such as this happen throughout the performance: the wrong tape is selected, or it is started at the wrong place, or the material he is looking for is on another tape reel. At one point toward the end of the performance, in preparing to perform the “Bluebird Asymmetry” with a group of readers, Mac Low accidentally arrives at the poem “Peaks and Lamas” on the reel-to-reel player, and simply lets the poem play while they all together wait and listen. ↩

Kate Eichhorn, “Past Performance, Present Dilemma: A Poetics of Archiving Sound,” Mosaic 42.1 (2009): 184. ↩

Eichhorn, “Past Performance, Present Dilemma,” 197. ↩

Lyn Hejinian, Language of Inquiry (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 323. ↩

Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge (New York: Routledge Classics, 2002), 129. Also quoted in Eichhorn, “Past Performance, Present Dilemma,” 183. ↩

Michel Foucault, Aesthetics, Method and Epistemology, ed. James D. Faubion (New York: The New Press. 1998), 289. ↩

The author thanks Kay Dickinson and Jonathan Sterne for their comments on early versions of this essay, and Nathan Brown and Heather Davis for their comments during revisions.

Article: Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.