love.abz at the Glicker-Milstein Theater, Barnard College, New York (April 16, 2015)

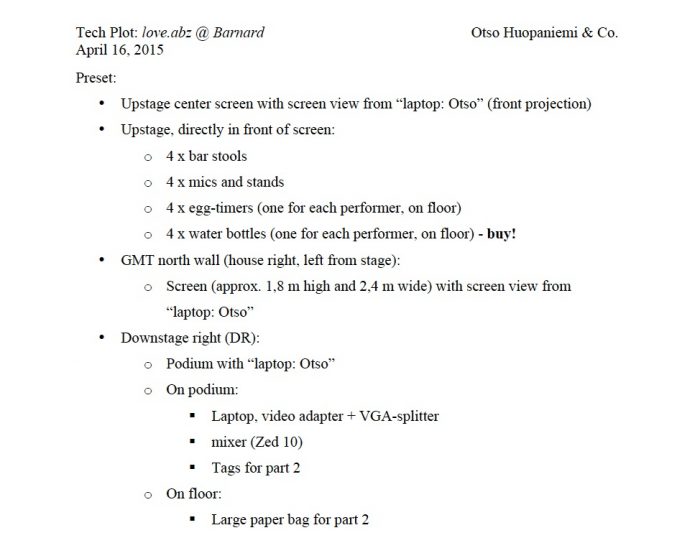

“Welcome, good crowd. This is LOVE.ABZ.” Such begins one iteration of Otso Huopaniemi’s theatrical work, a speech synthesizer addressing the crowd – sometimes “dear audience” – at the outset of a multi-act translational exercise for human and machine performers. Some aspects of the staging provide a legible frame: the central projection screen displaying the familiar interface of Google Translate, the director with his laptop executing the scripts and coordinating the actors who are positioned before microphones and noticeably anticipating their cues. But the content of the performance is by contrast decidedly less legible, or differently so. The mechanics are specified – Google Translate is both platform and medium; there are temporal constraints and the actors will be “live writing”; the audience will to some extent be participating in the chance selection of scenes; and speech recognition software will play a central role – but the language, so seemingly secure and certain in the opening address, is appreciably confused, deformed, garbled. It is also, importantly, not singular. Love.abz is after all about, and made possible by, machine translation, and the primary text of the play is only ever presented as input and output for Google’s translational system, initially with English and Finnish, the director’s two compositional languages, and then, in the performance I watched at Barnard in 2015, interspersed with German, Spanish, and Mandarin.1 The machine speaks: “Technology error estimates.” Comedy ensues.

Love.abz is however a serious work, no mere exploitation of a technical system or production of grammatical infelicities for momentary comic delight, but in fact a deeply informed research-based art project that thematizes and theorizes translation in the age of Google, when statistical machine translation was at its peak. The nominal source text is Huopaniemi’s original play in Finnish, An ABZ of Love, which had some autobiographical elements and was itself never staged.2 “Source” is however a fundamentally unstable category in the context of reiterative or “looped” translation, and indeed the Finnish text could only plausibly be granted chronological priority – such is the vertiginous effect of reduplicating the translational act. (As one so-named “autonomous digital actor” puts it during the Barnard show: “Closer to the originals, we can not at this time.”3 ) So too the notion of “source” is complicated by the incorporation of metacommentary, as well as the live improvised speech of the actors, into the textual field – more precisely, into the corpus or archive, which was developed throughout performances in New York, Berlin, Cardiff, Karlsruhe, and Helsinki (2011-2015).4 The logic is accumulative. Each performance and each translation, with all technological, linguistic, and human errors preserved, was recursively folded back on the last, the archive expanding to encompass all manner of glitch, from an actor’s stutter to statistical failure, and the series eventually culminating in what Huopaniemi here terms a “spectacularly Babelian” finale. Garbage in, messier garbage out.

The reference to Babel is not incidental. Indeed, love.abz is nothing if not an instantiation of the biblical narrative that, along with La Malinche, is one of the core mythologies of translation studies. Here though it is technological systems that confound, both named (Google, Dragon) and unnamed (operating systems, projection software), along with social use, the ordinary expressive activities of human speakers. And to extend the allegory, Babelian confusion is not punishment for hubris, for a failure to recognize the “natural” hierarchical order of things, but rather a puncturing of the residual belief in linguistic commensurability and provenance, our implicit faith that what is heard and read has been generated by a human author, that the actors speak their minds and the words emanate from their being. This then is love.abz’s primary contribution to the discourse on translation: the tacit posing of the question, what is the task of the machine translator?

In one of the acts, the human performers listen to a machine translation of an audience-selected play fragment that has been performed in real time and vocalized through a speech synthesis API. Their prescribed task is to interpret the given text and devise a responsive improvisational scenario that is to be fed back into Google Translate via Dragon’s speech recognition software. In the process, they collaborate, compete, and play with each other, at times commanding audience attention and at others lending their voice to the common stream that is, variously, interrupted, revised, supplemented. The true dramatic substance is however their negotiation of the technological apparati: how to train, how to use, how to partner, how to force a creative misfire, how not to submit, even how not to upstage. (In this regard, the actors are prosthetic extensions of the director whose project is to orchestrate creative destruction.) The digital characters – e.g. “Moira,” who speaks with a synthesized Irish accent – are presented as autonomous and they do indeed initiate conversational threads and contribute meaningfully to the performance, such that one can understand the first-person plural in the play’s framing statements to refer to all human and nonhuman actants. “I hope you enjoy the process with us,” the audience is told at the outset, with the full range of that “us” becoming ever more clear as the scenes unfold.

In one act, the human performers lie on the floor with eyes closed, collectively improvising a love story for blind machines, the effect of which is to remind the audience that there are multiple sensors and sense-making systems at work, from the exteroceptive faculties of the actors to the speech recognition software that captures their voices for the database out of which the next performance will emerge. This after all is the lesson of Katherine Hayles’s latest book, Unthought: cognition is a “broader faculty” shared by all biological life forms and many technical systems; meaning is not the exclusive province of the human; and we “do not have a lock on which contexts are able to generate meanings.”5 Cognizer then is first and foremost a role that many actors can play. There are arguably only degrees of difference between the processing of input, sense data on the one hand and speech on the other, just as the actors’ seemingly automated responses to dialogical cues bear more than a family resemblance to the output of Google Translate. So, too, if the language of An ABZ of Love could be imagined to be necessarily expressive of the psychic and romantic turmoil of the playwright, all of the spoken language of love.abz seems rather to be externally generated – symbolic production without signification and understanding. Franco Berardi situates such techno-linguistic automatisms in the context of semiocapital, which “puts neuro-psychic energies to work, submitting them to mechanistic speed, compelling cognitive activity to follow the rhythm of networked productivity.”6 Indeed, the deskilling of labor, its reduction to rote procedures, recasts work in terms of following a script, which is to say functioning like an algorithm. We are left then with the ontological transposition that summarily captures our socio-technical condition: machines impersonating people and people impersonating machines.

In the conjoining of live machine translation and live utterance, and within a writing space that splits apart and disperses the discrete grammatical unit, the words are perplexed in the full sense – bewildered, interwoven, entangled – proper origins unknown. This is an admixture, an amalgamation, so radical that it could only be representational, simultaneously reflecting and reproducing our contemporary techno-linguistic condition. While it might seem at first glance then that the move from An ABZ of Love to love.abz has been from dramatic representation to algorithmic permutation, the paradox is that each translation, distortion, and re-mediation of the original has brought the work more closely into alignment with the “real” out of which it ostensibly emerged. The task of the machine translator in such a milieu is to assist, more precisely to steer, not only in (1) the management of communication systems but also in (2) the appreciation of the very linguistic properties that would otherwise be expunged as unproductive, anomalous noise. Both necessitate a recognition of the human in the loop, a speaking to, a dynamic Huopaniemi is able to instantiate by mediating all direct communication with the audience through computational systems. In contradistinction to what Jonathan Crary describes as the “non-social model of machinic performance”7 underwriting the globe, 24/7, with total automation and instantaneous, glitch-free communication, Huopaniemi offers his audience, us, a model that is instead fundamentally social and performative.

–Rita Raley

It is difficult to imagine a more apposite creative text to feature in this special issue of Amodern on “translation-machination” than love.abz. I would like to begin with your account of its origins: could you recite once again the story of how this work came to be, and specifically how it evolved from its original, your script for An ABZ of Love?

One way of looking at it is that a series of failures led to love.abz. First, there was a failure of communication in my personal life that manifest itself, about four or five years later, in the form of the play An ABZ of Love, which I originally wrote in Finnish (Rakkauden ABZ, 2008). Second, the play itself was a failure, painful and tiring to write and probably more or less unpresentable as such. (In fact, I doubt whether anyone has ever read it from first scene to last, with the exception of my closest friends who have felt obliged to do so.)

Finally, another communication breakdown late in the 2000s led to the disintegration of a working group that I had been a part of for a couple years in New York (three performers and myself). This last failure prompted me to question the very point of writing and staging plays in the first place, a skepticism that wasn’t entirely new to me. So once I started experimenting with machine translation, and more specifically with Google Translate, this skepticism fueled an enormous desire to find new ways of configuring the relationship of text and performance, not to mention new ways of going about creating performances. I didn’t want to do away with text altogether, as I knew I was engaged with words for good, but I was definitely looking to give up writing practices that had clearly become unsustainable.

More concretely, love.abz began the moment I realized Google Translate was capable of translating entire documents. This was in 2010 – about three years after Google had switched to its own statistical machine translation technology. Around the time I had moved to the US to study, I had used Google and other websites to translate mainly my own texts from Finnish to English, and from English to other languages. When I noticed that I could do more than simply enter small bits of text into the website’s text-entry field, a sharp turn occurred. Google’s first translation of An ABZ of Love – which had such a visceral effect on me – was very noisy, in great part due to the fact that the program had no basis for dealing with the spoken Finnish in which I had written the script.

At the time, I was inspired by W.B. Worthen’s Performance Theory seminar, which I was attending at Columbia as part of my MFA studies in playwriting. Among other topics, we were discussing textuality and the ontological status of texts along the lines of, for instance, Joseph Grigely’s Textualterity (1995). Many things could be said of Google’s translation of my play, but what seemed certain was that it was, compared to any other translation I could imagine, radically other. In addition to the failures I had experienced in my personal and professional life, the discussions on what it meant to speak of an original, of textual correctness and finality, and difference, texts “drifting in their like differences,” as Grigely writes, allowed me to appreciate what Google had produced, and primed me for the work I was about to plunge into with Google Translate and later also with speech recognition.8

“Tech Plot,” love.abz, Barnard

You have said that love.abz “began as an experiment in machine translation” and then “evolved into a performance work,” which is a highly suggestive binary that I would like to explore with you a bit. To start, I wonder if there is a sense in which love.abz is also an experiment in performance; in other words, is there an implicit theory or conception of performance that is enacted by the work? Does the introduction of machinic actors and/or the mediatized theatrical apparatus, affect our understanding of performance in any way?

In addition to the discussions on textuality that I mentioned earlier, I am certain that Hans-Thies Lehmann’s Postdramatic Theater (2006) had a strong impact on the love.abz concept, although it again took me years to find the means to translate Lehmann’s assertions into working realities. Also, in the beginning the technique I used for composing the piece was more or less laughable: anything that I didn’t feel comfortable with I simply rejected. (No doubt this had to do with the stressful experiences I alluded to above.)

From Lehmann, I translated into practice the emphasis on actual processes happening in the real time of the stage. For me, this meant putting actual writing processes on display; something that would have been far more difficult had I tried to carry out the original idea of no human performers, just projected text and synthetic voices. Before our first performances, the actors would occasionally ask me to describe what it was that their characters were doing. They wanted to give it a label to help them structure their work. It took some further conversation to establish a common understanding that there were no characters, only performers enacting different tasks. What of course complicated this was that they continued to create characters in their improvised texts.

If one were to look at love.abz strictly from the perspective of bodily activities, what the performers are doing is speaking. Without the machinery, the speaking would never morph into writing. This has by no means been clear to all audience members. Having seen our performance at Prelude.11 Festival, the producers of an off-Broadway theater asked me, “So all the words we just heard were written by you?” This, of course, couldn’t be further from the truth.

As I soon realized, there were two parallel stages in love.abz, the physical stage that the performers inhabited and the digital stage visible on the screens. Dramaturgically, my task was to establish the relationship of these two stages and to find ways to allow the audience to access the gap between them. It’s the simultaneity and convergence of the physical and the digital that I hope would inform an understanding of performance taken from love.abz. It’s no longer a question of whether the screens take attention away from the human performers or vice versa. Both are comprehensible only through the other.

There is much that is striking about love.abz for any audience, but for translation theorists and practitioners your play with “source” and “target” is particularly rich. Could you talk a little bit about how your technique of reiterative translation, both within a single performance but also over the lifespan of the work, complicates our understanding of these categories? Could one extract or infer a new theory of the originary text from love.abz? And are there practical implications of the insights it offers about the relations between copy and original – in other words, does love.abz prompt us to understand the actual task of the translator in different terms?

Disgruntled as I was with working with actors and other performers, I initially envisioned love.abz as a performance without (human) performers, in the spirit that Beckett articulates: “The best possible play is one in which there are no actors, only the text. I am trying to find a way to write one.”9 However, then an actor serendipitously approached me and wanted to work together, which led to us asking another actor to join the production, and so forth. In the end, I was working with three actors, somewhat ironically, as there are three characters in An ABZ of Love. My original idea of a “pure” experiment in machine translation (and speech synthesis) was further compromised, for the better, when I – acting upon encouragement I had received from a number of people – started experimenting with speech recognition as well.

In the early productions of love.abz (3LD and Prelude.11), we were still very attached to Google’s (then) translation of the play. Before we got even remotely close to staging anything, though, I had amassed a small database of translation variations performed by Google. In a personal discussion with W.B. Worthen, the idea of taking Google’s translation of any given part of the play and having the program translate it back into Finnish came up. This “looping,” as it became known, was easy to do – basically, it only required enough patience to keep copy-pasting text back and forth – and fascinating to witness, as it seemed to demonstrate exactly how mutable and fluid texts are. Undoubtedly, it was also my attempt to learn how machine translation works – the idea being that if I just keep at it long enough, I will ultimately understand how the program works through the variants it produces. This proved to be a misconception, as I realized when the sheer quantity of looped material quickly started overwhelming me.

Rather than exhausting Google Translate, looping was exhausting the technique itself. Nonetheless, there was the sense that the technology was being pushed to some limit. After a certain number (six or seven) of back and forth translations, the text ceased to change or the changes became marginal in comparison to earlier changes. As Worthen pointed out, the texts appeared to reach some kind of uncanny synthetic stasis. In other words, source and target had transformed into each other, bled into each other, as it were, so many times that the resultant text could be seen to be as machinic as possible in these conditions. Whether or not this was the case, the looped texts had clearly travelled a considerable distance from their origin, my play. In some cases, they had shed almost all recognizable features connecting them to the play, with the notable exception of character names (although they, too, were sometimes transformed).

Addressing your question concerning source and target and their interrelations, I think what looping demonstrates is the ease with which these categories can be interchanged. As the looping process continues, it becomes harder and harder to retain a sense of what is acting as source and what as target, especially as noisy machine translations tend to be bi- or multilingual, meaning they contain untranslated traces of the other language (sometimes also of a third, intermediary language, although developments in machine translation have made this more rare). The way I understand Samuel Weber’s take on Walter Benjamin’s theory of translation, laid out in “Translatability I” and “Translatability II,”10 is this: if you look closely enough at any original, it too turns out to be a “mere” translation. That is to say, the ontological status of the original is hardly more stable or fixed than its translation. It, too, has mutated from something else, more or less directly, and continues to be just as mutable as all other texts.

In my view, what machine translation – and the architecture of machine translation websites – can bring to this discussion is a heightened awareness of the idea that virtually anything can act as an originary text; that a text takes on, performs, the role of an original when it is made to do so, and that it can just as easily lose this role when it is changed by its translation, be it algorithmic or not. Thus, the theory of the originary text that I propose, based on love.abz, is unsurprising: there is no original original, there is only that text which is chosen to function as original, for a wide array of (quite human) reasons. In this algorithmic era, the original can be deleted or replaced with a click or two. The choice of original is, nonetheless, as significant as ever, as its impact is felt through the many variants it gives rise to.

With regard to the task of the translator, I have for the past year or so been attracted to thinking of translation in terms of thinking. In other words, we have these two chosen positions of source and target (in the case of bilingual translation) or source and multiple targets (in multilingual translation), which can also be thought of in terms of stages or empty spaces, and the movement between them. For me, it is appealing to consider that this movement constitutes thinking and that whenever a linguistic border is crossed, thinking is involved (be it artificial or not). This, of course, is mainly applicable to situations where both source and target(s) are mutable – and not protected by copyright, for example. What I would like to propose is that the task of the translator is to think in and through translation, to continue changing both source and target until they reach a stasis (which is always a compromise of some kind), somewhat like the synthetic stasis I mentioned earlier. So the task then is to carry forward at least two parallel texts, rather than source and target, in at least two different languages, and to strive to benefit from the “cross-fertilization” they afford as they reflect back on each other.11

You write of the traces of the original script “becoming all the more opaque and imperceptible” but persistent nonetheless throughout the reiterative processes of translation – the feeding of output back into the machine as input, so to speak. The process, you suggest, is one of “mutation but not erasure, of transformation but not cancellation.” Particularly within the span of a single performance, as the language becomes ever more garbled in an ordinary sense, one might ask what is at stake in the holding on to the original, both as an idea and as material remnant. Is there a threshold that would mark an erasure or disappearance, a point past which the raw linguistic material was so transformed that it could no longer be recognized as love.abz, much less as language itself? Could you expand on your allusion to the Benjaminian “afterlife” in this regard?

In this case, what was at stake for me in terms of holding on and ultimately letting go of the original play was reworking my relationship with a model of authorship I had internalized and struggled to put into practice. In a sense, the script for An ABZ of Love marked the point where I had decided to make the shift, although I continued to write plays for some years thereafter and was not able to really implement the change until translation offered me the means to do so.

So, in the later parts of the love.abz series (Kiasma, Theaterdiscounter, Barnard), I consciously pushed the process further away from the originary text. In Kiasma, we were still using the fragments of the play looped by Google as impulses for the live writing. Although the performance differed dramaturgically from the performances in New York, in this regard it was not so different at all. By the time we got to Theaterdiscounter in Berlin, however, a significant shift had happened. The new performers, now speaking German, were no longer writing in response to the looped scenes of my play. Instead, the stimulus texts were looped versions of scenes written in the prior parts of the series, by other performers. Thus, the reference point changed. The connection to my play still existed – traces of it were still showing up in the new improvised scenes, although the audience no longer had any way of recognizing them – but now the performance series had started taking on more collective authorship of its own.

The question of the threshold beyond which there would be no trace of the original – or even of language, as you suggest – was present throughout the series. In (love.abz)3, the last part of the series, it was amplified in a way that I had not quite anticipated nor planned. We took apart the live writing method or rather introduced a deconstructed version of it that was performed in addition to the version we had established and performed up until then. This all sounds overly complicated, but what we actually did was very simple. Having noticed a long time ago that speech recognition engines continued to produce text even when the input language (the language the speaker spoke) did not match the language the program was programmed to recognize, we decided to exploit this characteristic to the extreme. We had three groups of three performers speak different languages to the software, most if not all of which (depending on an arbitrary draw) did not match the program’s language settings. Thanks to a remarkably multilingual group of performers (eleven languages in all), we were able to create a spectacularly Babelian final part of the performance and of the entire series. In the text generated in this finale, there were surely no recognizable traces of An ABZ of Love and few of language in any conventional sense. The screens filled up with individual words and phrases lined up as if they were language.

In connection with Benjamin’s concept of “afterlife,” Samuel Weber writes, “The reason, in short, why works are translatable, is that they have an afterlife. And they have an afterlife because in the process of living, they are also dying, or at least, departing, taking-leave from themselves and this from their birth.”12 It’s this “taking leave from themselves” that begins the moment a work comes into being that appeals to me, for reasons that I hope the above description has clarified. It is only through its numerous – potentially innumerable – translations that the work gains significance, life, which is perhaps easier to imagine in the case of a dead, unstageable play. Where I obviously depart from Benjamin is with regards to the translatability of translation: for him, translation is the limit, the threshold beyond which there is no further translation. “Translation transports the original into a sphere of limited reproducibility, in which it cannot live very long. Afterlife is not eternal life,” Weber writes.13 While I don’t want to claim eternal life for any text, I see translation as impetus to return to the original and rework it. Therefore, translation certainly does look back at the original, as it continues to contest and reword its meaning, endlessly.

A striking difference between love.abz and other exercises in reiterative translation – one good example of which is Baden Pailthorpe’s Lingua Franca – is that your source text is properly your own. What difference does it make that the originary text is not just of your own composition but also emerges to some extent from your own biography? How does the incorporation of the authorial “I” alter the dynamics of textual (self)destruction?

If I had to pinpoint what the difference boils down to, I would say that using your own text as source gives more freedom to move. There is a liberating aspect to it, especially perhaps in the case of the straightforwardly autobiographical writing I was performing as a playwright. It was not only the textual representations of fictionalized real-life situations that were transforming, but my understanding of them as well. The example I like pointing to is Google’s difficulty with translating the gender-neutral Finnish pronoun “hän.” In the case of An ABZ of Love, originally a ménage à trois between two male and one female character, this led to a far more dynamic situation in which the genders of the three characters were changing from scene to scene and even within individual scenes. I would stop short of saying there is necessarily a therapeutic aspect to such textual deconstruction, although the laughter such alterations give rise to certainly is cleansing.

From very early on, I’ve been asked why I don’t replace my obscure play with something more readily recognizable, like Annie Dorsen does with Hamlet in A Piece of Work and Baden Pailthorpe has done with Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four in Lingua Franca. The argument was that this would allow reader-spectators to get a better grasp of the textual transformations. Although I at first brushed off this critique, it stuck with me and I made various attempts at working with texts that were not my own. I even proposed a textual reworking of Büchner’s Woyzeck to a venue in Germany. The proposal didn’t lead to a production and my interest in this approach waned. Later, however, I teamed up with Finnish visual artist Pilvari Pirtola to do an experiment in intersemiotic translation (Mind Machine, Kiasma 2017) in which Pirtola’s demoscenevideos acted as the “source texts” for my live writing. Conversely, the live writing I did functioned as source texts for Pirtola’s live video mix, in a reiterative translation cycle structurally similar to that of love.abz.

Mind Machine proved to be a very liberating experiment in many ways, and I think there is still plenty more to explore in intersemiotic translation in and as performance. However, I feel this is something separate from the work I continue to do in translating my own texts and having them translated. In hindsight, I think my primary interest for the past ten years has been in that of the self-translator, even as the majority of my work in love.abz has involved facilitating the writing of others. Without wanting to reduce it merely to the deconstruction of an authorial “I” – which would be a misrepresentation of the work we have done – I now see the writing performed by the other performers as part of a broader process of self-translation, for the purposes of which I have engaged both human and machine co-writers.

The reiterative process is also one of decay and destruction, which calls to mind a whole host of artistic practices, from Andy Goldsworthy’s sculptures disappearing in the sun and wind to bpNichol’s repeated use of a copying machine to produce “generational disintegrations.”14 Of his Translating Translating Apollinaire 26, Nichol wrote, “the machine is the message. The text itself ultimately disappears.” Do algorithms transmit the same message? What difference, if any, does a computational environment make to an aesthetics of disintegration? Are there comparisons to be drawn between environmental and algorithmic agents of destruction?

The image of bpNichol photocopying his poems away is a beautiful one, as are the minimalistic images he created as a result. I can relate to his fervor for trying out different machines to see how they perform differently. For some time, I was trying to learn German by translating texts of mine with several different machine translation programs (Babelfish, babylon, Bing, and Promt, in addition to Google Translate). I doubt I learned much German in the process, but I did get a feel for the different “imprints” the machines were leaving. Ironically, although my German was anything but fluent, I was convinced that certain programs were doing a better job of translating certain sentences, while others fared better with other ones. I don’t know if bpNichol ever created collages of the photocopied images, but I would combine what felt like the best pieces of the various machine translations and present the resultant texts to my tutor to gauge if they made any sense.

If I were to rewrite Nichol’s words, I would suggest, “the algorithm is the message. The text itself keeps on changing.” Translation algorithms differ from the copying machines of the 1980s in that they don’t make the text literally disappear, or quite rarely in any case. Yet they certainly do call attention to the way they are transforming texts, to themselves, as their approach differs so completely from that of any human translator. I have toyed with the idea that the machine translator, in its algorithmic insistence on finding an exact equivalent for each and every word and phrase with little regard for context is quite like Benjamin’s ideal translator, whose slogan is: “Fidelity to the word, freedom toward meaning!”15 This analogy may have lost its relevance with the newest developments in machine translation – I’m referring to neural machine translation – with, among other things, its increased capacity to take context into consideration.

However, the more important point here is that, in a computational environment, the decay and textual destruction comes about from the system performing exactly as it is programmed to perform. To my knowledge, although algorithms are capable of learning and adapting to the environments in which they function, they do not – not yet anyway – have the capacity to evaluate in real time how they are doing in terms of translation accuracy. Such a simultaneous evaluation process would be incredibly complicated, as the methods for “post-production” machine translation evaluation demonstrate (BLEU being one of the most common algorithms used for this purpose). So just as the copying machine is performing its best to deliver a legible copy and producing artistically interesting objects as it fails to do so, translation algorithms are performing the task of translation according to the sets of rules and procedures that are written into them, their code. If the results appear as decay or destruction, it is not because the algorithms are failing. It is because writing the code that would allow a machine to translate natural language flawlessly into another natural language is just so challenging.

Looking at it from another perspective, the question of algorithmic agency is a complex one, as it extends into the physical environment in so many ways. I’m thinking of Kevin Slavin’s idea of algorithms as a “third co-evolutionary force” in addition to man and nature, and of Susan Schuppli’s discussion of “deadly algorithms.”16 In addition to carrying out many tasks with widespread benefits – Schuppli mentions pacemakers, early warning systems against extreme weather conditions, and satellite detection of potential ethnic conflicts – algorithms are, of course, often involved in acts of intentional and unintentional destruction. Drones use algorithmic profiling to identify and attack their targets. There are striking examples of what happens when this process goes wrong.

Drones and self-driving cars receive plenty of attention, but there is another important aspect in which algorithms extend their agency into the physical world. Slavin points to how parts of man-made infrastructure and the natural environment are being “hollowed out” and rebuilt to allow algorithms to work more efficiently. As Slavin and others have asserted, the internet may be a distributed virtual network, but it still depends on its physical infrastructure in order to function. The closer you are to the closest data center, the faster your algorithms are likely to work. This may not have much significance for most of us, but if you’re dealing in a high-frequency business such as algorithmic trading, it can make all the difference in the world.

One might also regard love.abz as a chance-based work in that looping the text back into the translation platform produces new meanings and new semantic associations. What, if anything, changes for you in the exchange of bpNichol’s copying machine for machine translation? Do the different technologies and techniques produce qualitatively different aesthetic effects?

I’m glad you bring up the question of chance. I remember reading through Google’s early translations with the actors. I think we all had a strong feeling that some parts were just simply random – I did, in any case. Therefore it felt natural to add other elements of chance to the performance, such as the blind draw, in which the audience helped to determine which looped scenes would be used in a particular performance. Later, as I learned more about how machine translation works, I understood that there was nothing random about the algorithmic processes themselves. No matter how mystifying a particular translation could be, it was not the result of any blind lottery. This appearance or impression of randomness, however, was so strong that it had a mighty effect on how the performance was perceived and experienced.

What I was getting at in my reply to your previous question could be put another way. What are the forces of decay? In other words, what is causing the destruction? In the case of the copying machine, it is the gradual decline of legibility from copy to copy. In algorithmic translation, I would say it is something quite different. The algorithms keep translating in exactly the same way no matter how many times the text has already been translated. In “Linguistic Capitalism and Algorithmic Mediation,” Frederic Kaplan points out that algorithms are not well equipped to detect text that has already been algorithmically altered.17 This is part of the “linguistic wars” Kaplan speaks of, in which search engine algorithms strive to produce plausible search results, while other algorithms work to corrupt these same results.18 For love.abz, what is significant is that the cycle of algorithmic alteration just keeps on going, endlessly, or at least as long as the system works. There is no point where a blank page shows up, as there could conceivably be when even the last dots on bpNichols sheets of paper disappear. Returning to Benjamin, the effect is of a limitless afterlife rather than a confirming finitude, albeit as the looping process continues, as I mentioned above, the textual changes become more and more marginal.

What quickly becomes evident when one is in the audience is that love.abz compels attention to mechanics, staging, and language itself rather than meaning – in other words to attend to media and material form rather than semantic content. While the exploitation of the gap between sense and nonsense, between the semiotic and the asemiotic, is not itself new, I am convinced that there is something distinctly contemporary about an artistic practice that does not just occupy the space between, but also embraces meaninglessness on its own terms. (I am here thinking of Giorgio Agamben’s definition of the contemporary as that which has “a singular relationship with one’s own time, which adheres to it and, at the same time, keeps a distance from it.”19 ) As love.abz moves further and further into the space of noise, does it take on a political valence in this sense, or is there an aspect of cultural critique in the actors’ performance of a script that reflexively thematizes itself but says nothing at all? Put another way, is there a way in which you think love.abz – particularly in its immersive and disjunctive use of translation technologies – might be read as an implicit or explicit response to a more general crisis of language and signification in the present moment?

I wonder if there’s ever been a time when language and signification have not been in crisis. In this algorithmic era, the crisis has to be staged differently though. The self-righteousness of language, signification, and authorship definitely deserve to be challenged and poked at. As I had learned and accepted the idea that artists do things via themselves and their own practice, it was clear that I had to start with something I had created myself.

If language transformed almost beyond recognition could continue to produce new meanings and new associations, even convey parts of the original narrative of An ABZ of Love, why had we been so hung up on carefully creating scripts that made sense in the first place? It seemed like what was more meaningful was giving into the play with the (new) medium. Out of that a meaning would emerge that was more immediate and striking than any formally scripted one. In more practical terms, this often meant taking what the algorithmic technologies offered in the form of mistranslations and misrecognitions and incorporating them into the writing processes. Clutching on to authorial control – which speech recognition technology certainly allows – often led to writing processes that simply felt more ordinary. They did not surrender to the algorithmic suggestions, did not dare go in directions that opened up in the moment of the live writing itself. Even if this surrender or letting go meant ending up with a text that said nothing at all, the process leading up to it often certainly did say something.

A comment by fellow playwright Jesse Longman that made me very happy was, “Anything that made sense became über-sense.” This was a reaction to Google’s early translations, not to any staged experiment of ours (we hadn’t yet gotten that far). Even so, it captured something of what I, too, found so compelling in all the noise. Sense didn’t really start making sense until it emerged from the cracks of a wall of nonsense.

I can not help but remark on the (un)timeliness of this exchange: we are in the midst of a revolution of sorts in machine translation, with the ground fast moving beneath our feet. How would you describe your thinking about working with Google now, in 2017, and how if at all has your relationship to the Translate platform changed, now that it uses a neural machine translation system? Has it made a difference to your thinking about the script, or even the work itself? Are the translations, particularly between English and Finnish, equally unpredictable, and are the surprises of semantic accidents and miscues as readily available? Joe Milutis, who is also featured in this Amodern issue, has wryly observed of earlier uses of GT as a beatbox – no longer possible – that “It is a truism for the experimental translator that as Google Translate gets better, it actually gets worse.”20 Is Google now “getting worse” for love.abz in the same way?

Conceptually, what I find most fascinating about the “neural network invasion” is the “interlingua” it enables. No longer is it necessary to construct separate machine translation systems for all language pairs – systems that tend to use an intermediary language, usually English. As Christopher Manning points out, “if you have an interlingua in the middle, you only have to translate to and from the interlingua,” a change that also makes “zero-shot translation,” i.e. translation in a language pair that the system has no prior experience of, possible.21 What also intrigues me is hearing computer scientists talk a lot about attention, which, as I understand it, refers, in this context, to the translation system’s capacity to take context and the textual surroundings into consideration (neural machine translation has adopted a lot from machine vision).22 The irony of course is that as human attention becomes a scarce resource, algorithmic attention seems to be on the rise.

Google has not yet announced that Finnish is among the languages for which it provides neural translation, although something has clearly happened. This became very evident when we were rehearsing for Mind Machine in Helsinki in May 2017. Google had grown noticeably worse at translating from English to Finnish. Unlike before, it was producing non-existent words (with missing or unnecessary umlauts, for example) and severely truncating longer passages. As my colleague Pilvari Pirtola (who writes code as a part of his artistic practice) commented, the impression was that the system simply hadn’t yet learned enough (if it indeed had been switched to a neural one). Some weeks later, I was having Google translate another playscript of mine from German to English, and there I had the opposite impression. In that case, Google seemed to have gotten significantly better (or worse, for that matter), judging from the relatively low number of unquestionably noisy translations it produced when translating a scene of approximately 1000 words.

At the moment, I actually have a better feel for how the incorporation of systems developed in artificial intelligence research have changed speech recognition, machine translation’s sibling technology. Single-speaker speech recognition in English is getting to be so accurate that there is a danger it will narrow down the possibilities of using it for performative purposes (which depend on its less-than-perfect accuracy). Writing with English speech recognition, I had so much control over the text in Mind Machine, that another working group member, set and lighting designer Heikki Paasonen, actually asked me to let go of some of this control and allow the software to intervene more. He was undoubtedly right in pointing out that otherwise the live writing process lost much of its appeal. So, in a sense, as the technologies become better, the space for performance needs to be rediscovered and re-established, carved out again. As the mistranslations and misrecognitions become subtler, so does the interaction as a whole. However, to not get carried away, it’s good to remember that both technologies continue to produce a fairly steady stream of noise, depending of course on the chosen languages and software. The game is not over, even with the onset of neural translation, if indeed it will ever end.

“Google art” – no doubt an imminent database category, if it is not already – would include a range of practices, techniques, and technologies, from John Cayley and Daniel C. Howe’s How It Is in Common Tongues to Paolo Cirio, Street Ghosts and even the tumblr site, The Art of Google Books. What for you are the challenges and affordances of working with Google? What can we learn from such artistic exploits? How do you understand Google: as partner, instrument, medium, host, even sponsor? Can love.abz be read as an intervention or comment upon Google itself?

I think of Google Translate as a medium. At best, it is a medium of thought. Google has not necessarily always provided the best or most interesting translations, but its website has always been the most workable for performance purposes. Its interface has two major advantages in this regard: it is (relatively) uncluttered and shows the translation-in-progress as it is generated in the target field. The latter is enormously important for a piece focusing on textual transformation. (I notice that Bing now also offers this function, which might be cause for further exploration…) The former has made it possible to project the website on walls and screens and have the audience and performers view it without too much difficulty, even from relatively long distances.

As Kaplan points out, Google is only able to maintain and develop free interfaces such as Google Translate because it is making so much money through online advertisement auctions, i.e. through the selling of keywords.23 In this regard, an artistic project such as love.abz that is dependent on such websites is exploiting an offshoot of linguistic capitalism, as Kaplan calls it. Another way of describing it is that Google is “enclosing” language, as Daniel Howe remarks.24 In any case, this is obviously a paradoxical position to be in for an artist interested in language: writing with, through, and literally in a system provided by a corporation that seeks to take possession of words and language in general. This is why I have found your formulation, “writing with and against Google” so tremendously helpful.25 In a very concrete sense, this is what is happening in the performances of love.abz, both on stage and on a meta-level. “Writing with” in the sense of incorporating part of what the algorithms are suggesting. “Writing against” in the sense of resisting the influence of automated processes that work to shape languages in ways that make them more practicable for other automated processes. If there is no space for resistance, there is no performance.

We first met during a conference that featured W.B. Worthen’s reading of Annie Dorsen’s A Piece of Work along with a performance of love.abz.26 Dorsen has written of her practice of “algorithmic theater” as one that is “not particularly concerned with forms of representation” and as a challenge to theatrical axioms of embodiment, ephemerality, and language as a representation of consciousness and interiority.27 I wonder first if your thinking about embodiment with respect to love.abz – not just the relations among the performers, but also the relations between performers and audience – would be in sympathy with hers. So too I wonder if the archival component of love.abz, with the script of each performance incorporated into the corpus, would similarly complicate the ephemerality that has historically been accepted as axiomatic for theater. Does her definition of “algorithmic theater” resonate for you and your work, or do you have a different notion of what it might entail or what is at stake in the introduction of algorithms as collaborators?

I have great admiration for Annie Dorsen’s work and also for the work she has done in conceptualizing algorithmic theater. Her project is broader than mine in that she is interested in algorithmizing all aspects and parts of performance. In contrast, I am focused on writing and how algorithms participate in staged writing processes. Although I find the idea of having algorithms direct, design, and execute performances intriguing, it is in writing processes that the collaborative work with them really becomes exciting for me. Thus, for me, the question of embodiment is foremost a question of embodying translation. The human performers embody it and, in a very different way, so does the writing-translation machinery. Leaving the audience alone is not so much my aim as is giving it the means of witnessing and accessing this process, to the degree that it is possible.

With regards to ephemerality, the basic performative units in love.abz are the timed sequences of improvised writing, which last for some minutes and are structurally identical. These processes are not reproducible as such, however, even if the structure is exactly the same, down to the smallest detail. The resultant text is different each time. Even if I were to ask the performers to utter the same exact words in the same exact way and order (which I would never do), the likelihood of the human-computer interaction leading to an identical result is exceedingly small. In this sense, algorithmic theater as I practice it is ephemeral. I can reconstruct the processes with the help of video documentation and my archive of texts created in the performances, but that’s as far as I can go. The processes themselves are one-shot affairs.

It seems to me that algorithmic performance is occurring everywhere humans and digital technologies are interacting, not to mention algorithms interacting with each other. From my perspective, the task of algorithmic theater is to delimit some aspect or part of this interaction and detach it from its quotidian context. Re-contextualizing and highlighting certain algorithmic procedures has the potential of allowing spectators to regard our current algorithmic culture differently, perhaps even reflect on their own behavior within it. I suspect that for many audience members it was not so important that love.abz zeroed in on writing processes. Their experiences of the quirky interfacing of humans and technologies could have been similar even if we had staged other algorithmic processes. For us, the opposite was true: in order to get to the root of the matter, we had to stick with our algorithms of choice.

To pursue this line of thinking, I wonder if you might sketch an account of the different roles that algorithms play in love.abz, whether in terms of actor, director, choreographer, or instrument for producing chance operations. How do you understand the relations between algorithms and the embodied human performers on the stage? Would it be meaningful to characterize these relations in terms of Karen Barad’s notion of “intra-actions,” suggesting a kind of co-constitutive and entangled agency?28 Is there a sense in which love.abz implies a heuristic of ‘human’ and ‘algorithm’ (emotional/mechanistic; consciousness/automation; live/dead) that it then dismantles or otherwise complicates?

With the exception of (love.abz)3 – in which the parameters for each round of writing were algorithmically drawn using a random number generator – the algorithms in love.abz exclusively participated in the improvised writing processes. In other words, the only roles the algorithms played were that of speech recognizer and machine translator. In addition to translating the text produced live on stage, Google’s algorithms translated the introductory texts that were used in different ways to guide the audience into the performance.

So, in this respect, our use of algorithms was limited to two very specific tasks. I am fond of thinking about the relationship of the human and algorithmic performers in terms of technogenesis, the concept N. Katherine Hayles discusses in How We Think – Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis.29 From this perspective, the question is how human performers evolve – linguistically, cognitively, biologically – in relation to algorithms and how, conversely, technologies continue to develop in relation to humans (as machine translation fortunately has). Rather than Barad’s “intra-actions,” I have, at least up until now, been drawn to Hayles’s description of the interactions that technogenesis implies: “The interactions are dynamic and continuous, with feedback and feedforward loops connecting different levels with each other and cross-connecting machine processes with human responses.”30 It is these connections that make it possible to approach the question of how technogenesis manifests itself in the lifespan of a performance series, if it indeed does (evolution is, after all, slow).

In some of the reviews of love.abz, the opposition of man and machine was given great importance. The performance was seen to present a hyper-technologized, even sterile environment that, paradoxically, felt very human. Instead of a technological dystopia, love.abz was seen to present a humoristic struggle for survival.31 Although these descriptions reveal relatively conventional ways of modeling the relationship of humans and technologies, I take them to indicate that we were able to complicate some of the binaries you mention. Going further, I would claim that, in this era of contemporary technogenesis (the co-evolution of humans and digital technologies), associative and algorithmic processes are so thoroughly intertwined that automation has become a part of our thought processes in an unprecedented way. If love.abz was able to provide a glimpse of how such a development could manifest itself in the act of writing, I would consider that a success.

What role does synthesized speech play in love.abz and what can we make of the concluding act, which, in the performance I attended, was the automated recitation of transcribed and translated text?

Without speech synthesis, the equation would have been incomplete. If the speech recognition and machine translation algorithms performed writing, it was up to the speech synthesis algorithms to perform reading. We used computerized voices a lot in rehearsals – in fact, the actors’ first encounter with Google’s early translation of An ABZ of Love was a synthetic reading of it. We began by trying to mimic it.32

I realize now that reading is, of course, an important addition to your question above about the tasks the algorithms performed in love.abz. In the performances, the human performers read with, listened to, and responded to speech synthesis. Occasionally, it would accidently be activated during speech recognition (the program misinterpreted a word or phrase meant to be transcribed as such for a software command). This resulted in a surprising “speak back” on the part of the computer, which often then led to a spontaneous counter-reaction from the human performer. It was playful, unpredictable moments like this that gave love.abz its feel of liveness.

To the question of the ending, I have no real answer – other than all other options had been ruled out for one reason or another. Giving the last word to a synthetic voice seemed like the only way to go. If we struggled with some aspect of the ending, it was choosing which one of the many synthetic voices would be the most natural choice.

The Barnard performance was directed by Huopaniemi and performed by Catherine Copplestone, Emily Gleeson, Federico Rodriguez, and Eeva Semerdjiev (April 16, 2015). For complete video documentation of the event, which was organized by Hana Worthen as part of a series on “Performance, Technology, Translation,” see https://vimeo.com/126249275. Languages incorporated throughout the multi-year run of love.abz include Spanish, French, Mandarin, Hebrew, Finnish, German, Swedish, Bulgarian, Catalan, Polish, Spanish, Czech, Welsh, often reflecting the nationalities of the local actors. ↩

The original play itself has a partial source in Inge and Sten Hegeler, An ABZ of Love (1963). ↩

http://www.loveabz.com/productions/barnard ↩

Photographic and video documentation of the performances available from Huopaniemi’s Vimeo channel, https://vimeo.com/huopaniemiotso/videos ↩

N. Katherine Hayles, Unthought: The Power of the Cognitive Nonconscious (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 26. ↩

Franco “Bifo” Berardi, “Cognitarian Subjectivation,” E-flux #20 November 2010, http://www.e-flux.com/journal/20/67633/cognitarian-subjectivation/ ↩

Jonathan Crary, 24/7 (New York: Verso 2013), 9. ↩

Joseph Grigely, Textualterity: Art, Theory, and Textual Criticism (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996), 119. ↩

Deirdre Bair, Samuel Beckett: A Biography (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978). ↩

Samuel Weber, Benjamin’s -abilities, (Cambridge: Harvard UP), 2009. ↩

Rainier Grutman, “Self-translation,” Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, ed. Mona Baker and Gabriela Saldanha (NY: Routledge, 2011), 257. ↩

Weber, Benjamin’s -abilities, 66. ↩

Weber, Benjamin’s -abilities, 67. ↩

bpNichol, Sharpfax Copier Sequence: Selections from TTA 26 (1980), https://www.thing.net/~grist/l&d/bpnichol/bpsh.htm ↩

Quoted in Weber, Benjamin’s -abilities, 73. ↩

Kevin Slavin, “How algorithms shape our world,” TED (2011), https://www.ted.com/talks/kevin_slavin_how_algorithms_shape_our_world/transcript . Susan Schuppli, “Deadly Algorithms,” Radical Philosophy 187 (September/October 2014), https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/commentary/deadly-algorithms ↩

Frederic Kaplan, “Linguistic Capitalism and Algorithmic Mediation,” Representations 127.1 (Summer 2014), 61. ↩

Kaplan, “Linguistic Capitalism,” 58. ↩

Giorgio Agamben, What is an Apparatus?, trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Stanford: Stanford UP, 2009), 41. ↩

Joe Milutis, “Bright Arrogance, Gallery B: Transduction, Transposition, Translation,” Jacket2 (May 8, 2015), http://jacket2.org/commentary/bright-arrogance-gallery-b ↩

Christopher Manning and Richard Socher, “Lecture 10: Neural Machine Translation and Models with Attention,” Youtube (April 3, 2017), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IxQtK2SjWWM ↩

Navdeep Jaitly, “End-to-End Models for Speech Processing,” Youtube (April 3, 2017), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3MjIkWxXigM ↩

Kaplan, “Linguistic Capitalism,” 59. ↩

Scott Rettberg, “‘How It Is in Common Tongues’ – An Interview with John Cayley and Daniel Howe,” Vimeo (November 3, 2012), https://vimeo.com/59669354 ↩

Rita Raley, “Algorithmic Translations,” CR: The New Centennial Review 16.1 (2016), 133. ↩

“Performance, Technology, Translation,” The Barnard Center for Translation Studies

and the Department of Theatre (April 16, 2015). ↩Annie Dorsen, “On Algorithmic Theater” (2012), http://anniedorsen.com/useruploads/files/on_algorithmic_theatre.pdf ↩

Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham: Duke UP, 2007). ↩

N. Katherine Hayles, How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 2012. ↩

Hayles, How We Think, 13. ↩

Maria Säkö, “Kun tietokone saa viimeisen sanan” and “Yleisö todistaa Mind Machinessa ihmisen haurautta,” Helsingin Sanomat (February 21, 2013 and May 21, 2017), http://www.hs.fi/kulttuuri/teatteriarvostelu/art-2000002615166.html and http://www.hs.fi/paivanlehti/21052017/art-2000005219339.html ↩

Editors’ note: the structure of each performance was determined during rehearsals. ↩